How States Transformed Criminal Justice in 2020, and How They Fell Short

This year of crises, revisited: Nearly 90 state-level bills and initiatives. 16 themes. 7 maps.

Daniel Nichanian | December 18, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

This year of crises, revisited. Nearly 90 state-level bills and initiatives. 17 themes. 7 maps.

Criminal justice reform advocates called for sweeping changes in this challenging year. But state officials and legislatures largely ducked the COVID-19 pandemic that is raging inside prisons and jails, and the protests against police brutality and racial justice that followed Breonna Taylor and George Floyd’s murders. With some exceptions, they forgoed the sort of reforms that would have significantly emptied prisons amid the public health crisis or confronted police brutality and racial injustice in law enforcement.

Still, on other issues there was headway, and states—whose laws and policies control a lot about incarceration and criminal legal systems—set new milestones: They decriminalized drug possession, expanded and automated expungement availability, repealed life without parole for minors and the death penalty, and ended prison gerrymandering, among other measures.

Throughout the year, The Appeal: Political Report tracked bills, initiatives, and reforms relevant to mass incarceration. Just as in 2019, here’s a review of major changes states adopted in 2020.

Jump to the sections on: the death penalty, drug policy, early release and parole, youth justice, policing, fines and fees, pretrial detention, trials and sentencing, voting rights, expungement and re-entry, prison gerrymandering—and then there’s more.

The death penalty

In March, as the Trump administration was preparing to restart federal executions, Colorado abolished the death penalty, fulfilling a longtime goal for state advocates. Governor Jared Polis, a Democrat, also commuted the sentences of the three people who were on Colorado’s death row.

“The country is one state closer to having a majority of states ban the practice,” David Sabados, executive director of Coloradoans for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, told the Political Report at the time. Colorado is the 22nd state to repeal the death penalty.

Bills to outright abolish the death penalty did not move forward elsewhere. Virginia did end the secrecy that protected the manufacturers of execution drugs. Nebraska Governor Pete Ricketts, a Republican, vetoed a bill that would have required that witnesses be allowed to see the entirety of an execution. (Ohio is still considering a bill this month that would restrict the use of the death penalty against some people with mental illness.)

Opponents of the death penalty gained new allies in November with victories by prosecutorial candidates who have pledged to never seek it and advocate for its legislative repeal.

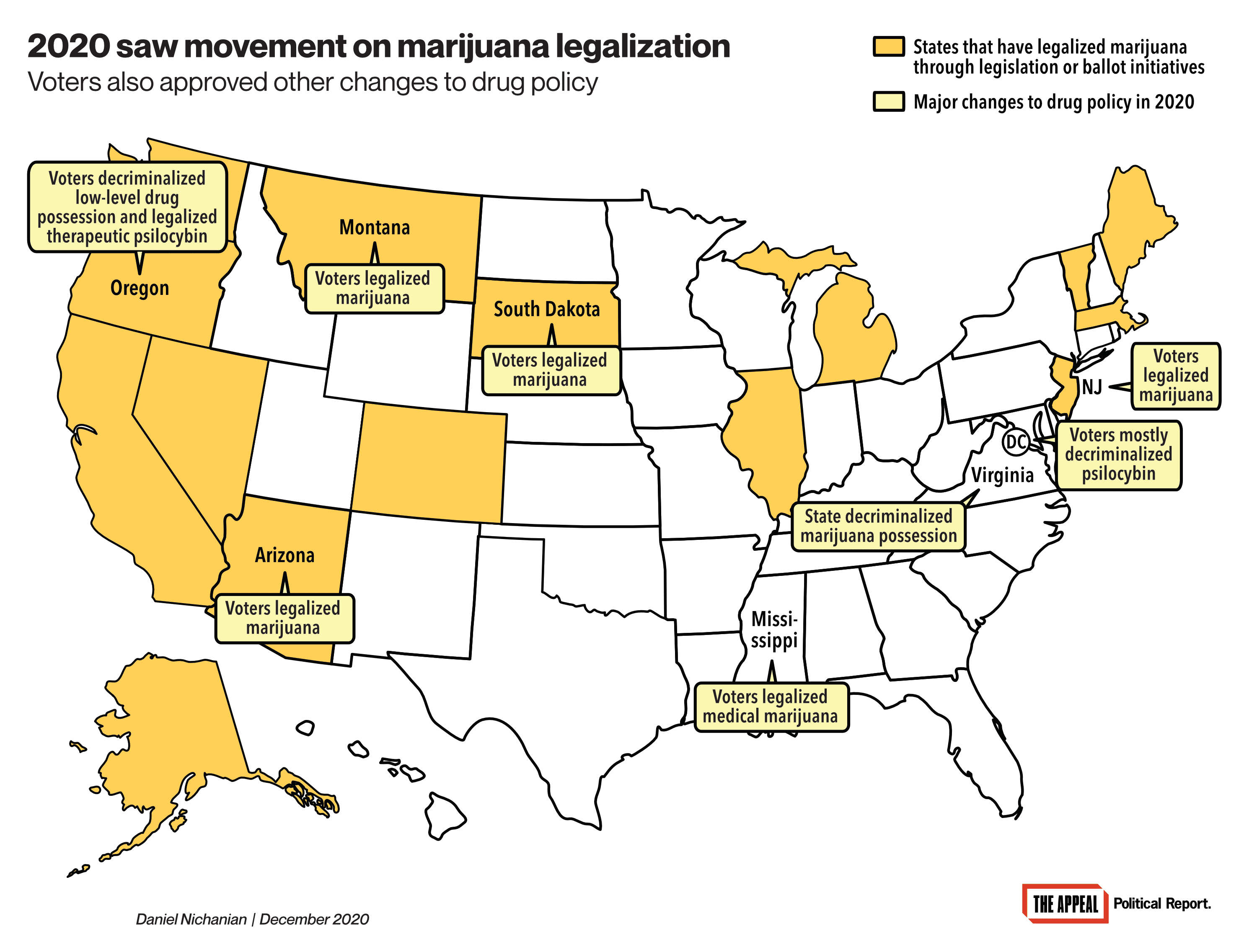

Drug policy

Oregon broke new ground this year when voters adopted a ballot initiative that decriminalizes drug possession. Measure 110 will treat low-level drug possession as a civil offense, punishable by a fine rather than jail or prison time, and it will fund public health programs.

Advocates say the measure could transform debates around the county by offering a new model for drug policy, even as more work is needed in Oregon to reduce enforcement and inequalities.

Other states focused on marijuana reform. In October, Vermont’s legislature created a legal system of marijuana sales. Then, in November, voters in Arizona, Montana, New Jersey, and South Dakota legalized recreational marijuana. There are now 15 states, plus Washington, D.C., where recreational use of marijuana is legal.

Also, Virginia adopted a law decriminalizing marijuana possession, but legalization stalled. Political leaders there, as in New York and other states, have signaled they may push further in 2021. Separately, ballot initiatives legalized psilocybin mushrooms for therapeutic purposes in Oregon; mostly decriminalized psilocybin in D.C.; and legalized medical marijuana in Mississippi.

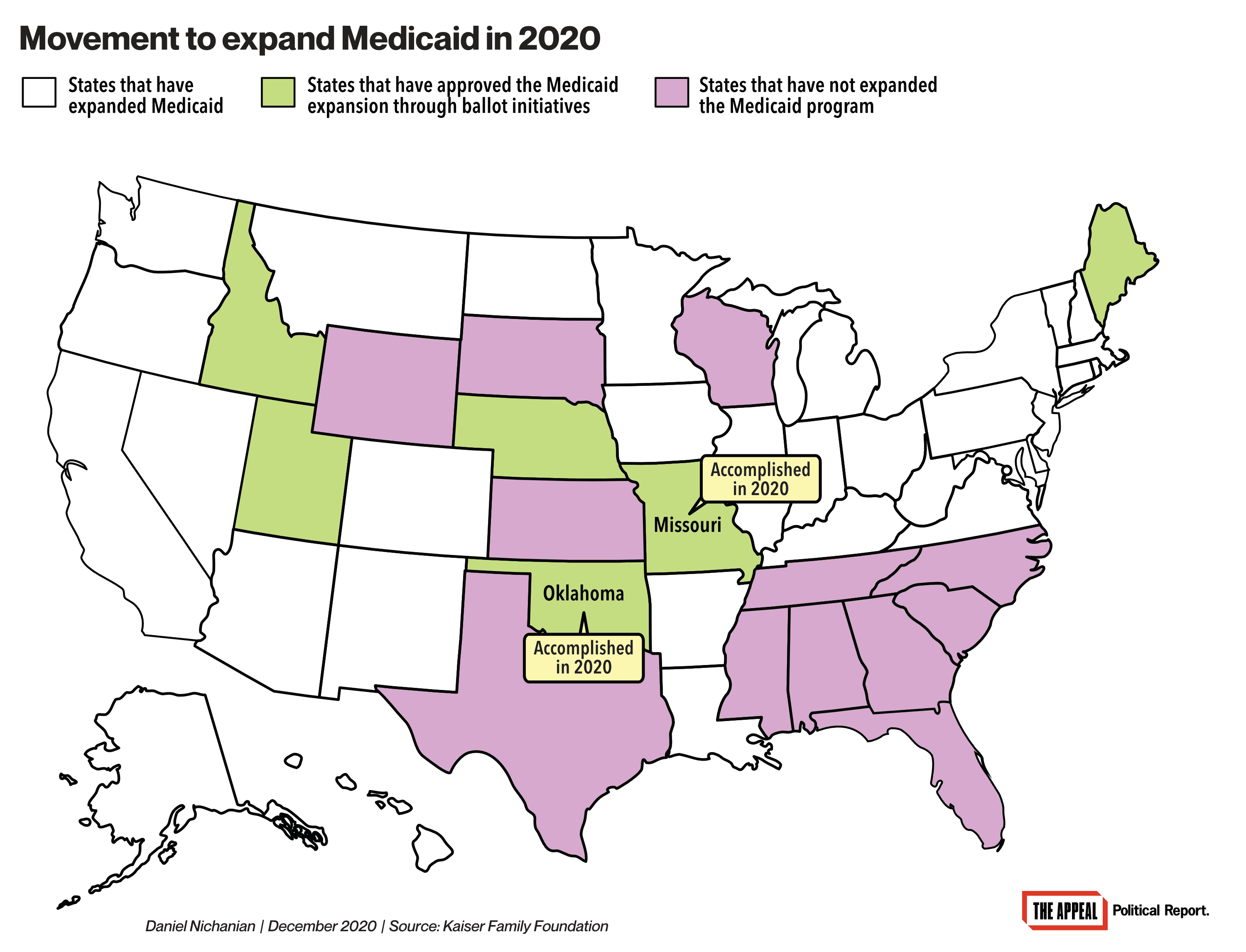

Finally, in Missouri and Oklahoma, voters opted to expand Medicaid, furthering a trend of voters in red states circumventing Republican lawmakers who have blocked expansion via initiatives. These two measures will grant public insurance to an estimated 500,000 people.

Among many benefits, expanding Medicaid can combat the overdose crisis and assist efforts to reduce the criminalization of substance use by enabling access to treatment programs. This link also resonated in 2018 initiative campaigns in Idaho and Nebraska.

Early release and parole

With the outbreak of COVID-19, prisons and jails that are overcrowded and confined promptly became virulent hotbeds for the virus, making up many of the country’s largest sources of infections. This sparked widespread demands for public officials to take meaningful decarceral measures to protect people in prisons and jails, and the surrounding communities.

Officials responded at a glacial pace, especially when it comes to emptying prisons. The Justice Department made release from federal prisons harder; Pennsylvania and Alabama left medically vulnerable prisoners without recourse when they canceled hearings; Ohio, New York, Delaware, and Vermont officials resisted calls for release or stalled release plans. “States are not even taking the simplest and least controversial steps, like refusing admissions for technical violations of probation and parole rules,” the Prison Policy Initiative wrote in an analysis.

In the fall, New Jersey was an exception to the general indifference: It adopted a law in October that granted many people incarcerated in the state with early release. As a result, more than 2,000 people were released on Nov. 4, in what the New York Times described as “one of the largest-ever single-day reductions of any state’s prison population,” with more releases to come.

Other states considered legislation to expand releases, often apart from the immediate context of COVID-19. Beyond the pandemic, those hoping to cut the size of prisons have been pushing for ways to modify the lengthy sentences people are serving around the country. On this front, a significant change may still be on the horizon this year: The D.C. council passed a “Second Look” bill this week that would enable people serving lengthy sentences for a crime they committed before they were 25 to petition for resentencing after 15 years in prison. The fate of the bill remains unclear given the mayor’s opposition, though.

Elsewhere, at least three states expanded parole eligibility.

California expanded eligibility for the state’s elderly parole process, and made people eligible at age 50 instead of 60. Louisiana, one of the harshest states for life in prison sentences, made some dent in that: Some people convicted for crimes they committed as children will now be eligible for parole after 25 years of incarceration if they fulfill a list of conditions. Then, there’s Virginia: The state eliminated parole in 1995, and did not broadly reinstate it in 2020, but still took incremental steps to revive it. It ended sentences of life without parole for children (see below); it made most people sentenced between 1995 and 2000 eligible for parole; and it did the same for some people who are terminally ill.

But in some states, promising reforms ended up derailing. Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves and Nebraska Governor Pete Ricketts, both Republicans, vetoed bills that would have made some people eligible for parole earlier than scheduled. Maryland lawmakers seemed on their way to ending governors’ effective veto power on anyone serving a life sentence getting parole, but the bill stalled in the Senate. In Arizona and Florida, advocates prioritized curtailing “Truth in Sentencing” guidelines that bar release until people have served at least 85 percent of their sentence, but these bills also did not move forward.

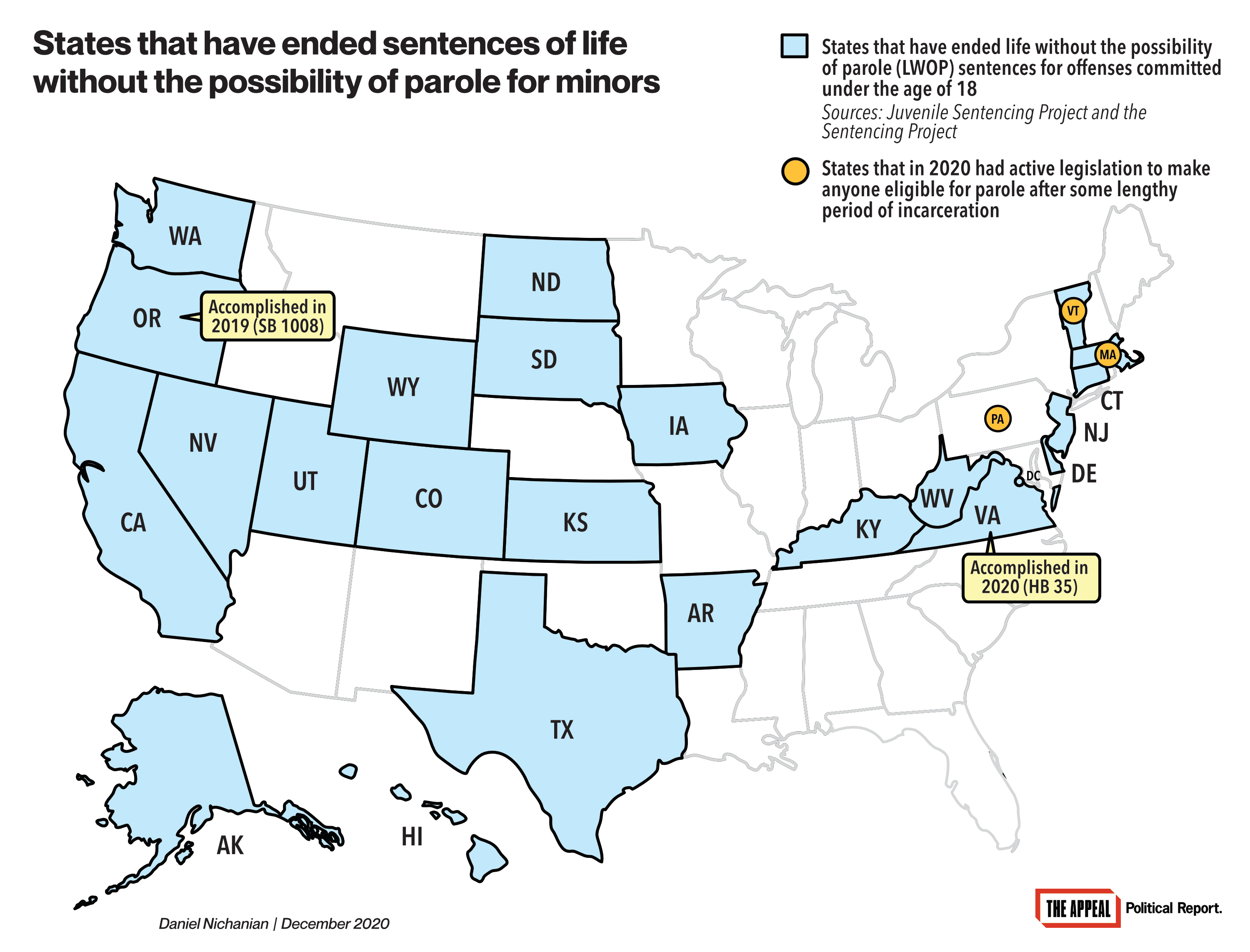

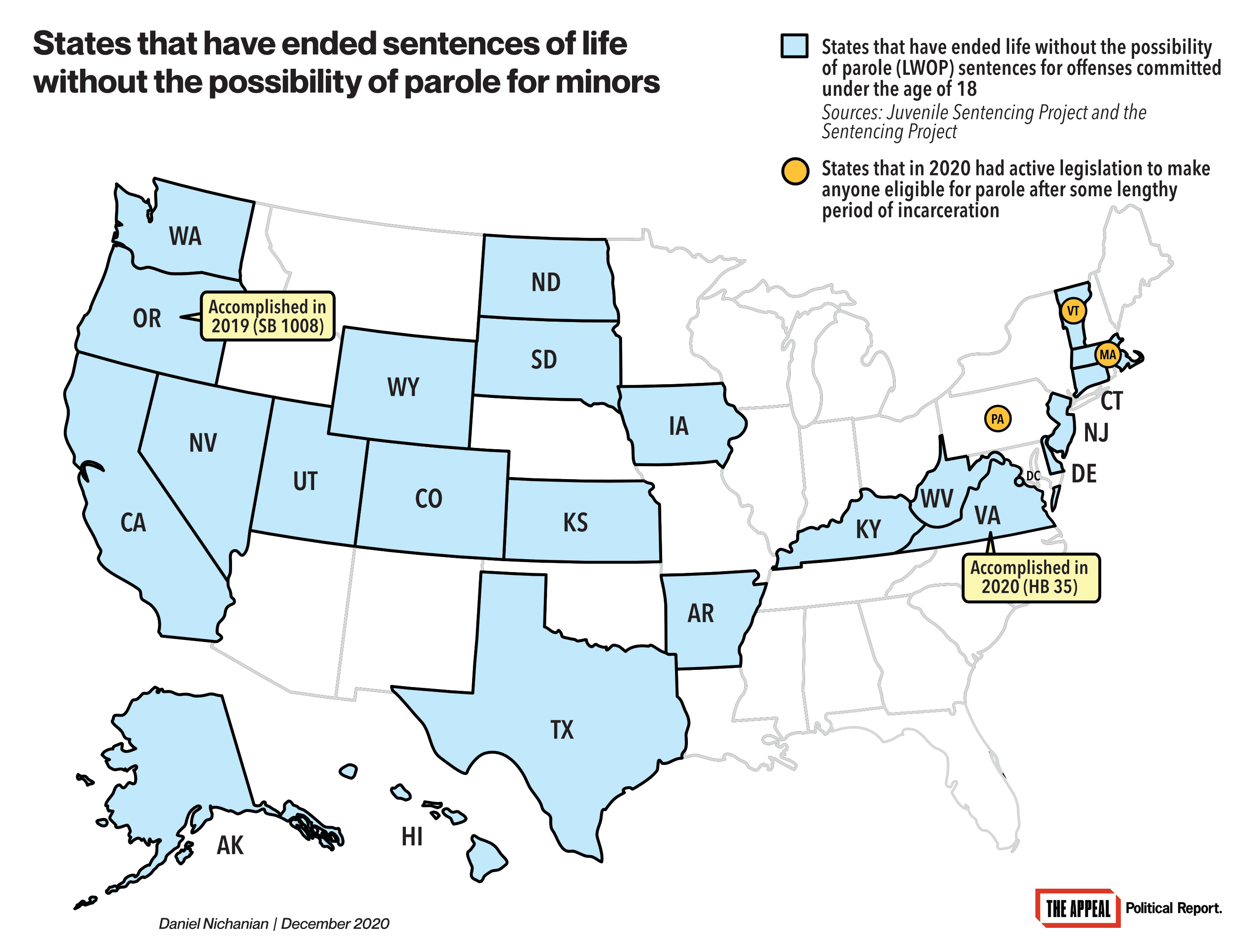

Youth justice

Virginia abolished sentences of life without the possibility of parole sentences for minors, the 23rd state to do so. “It’s a huge victory,” Heather Renwick, legal director of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, said at the time.

The Virginia law, which applies retroactively, will give hundreds of people who have been incarcerated for at least 20 years a shot at petitioning for release. (Ohio may still adopt a reform to end life without parole for minors before the end of the year, via a bill that remains alive as of publication.)

Also, Virginia and Utah narrowed the circumstances in which a minor will be treated as an adult, a designation that triggers harsher punishment; Utah’s law also restricts prosecutors’ authority to unilaterally decide to charge children in adult court. Still, whereas 2019 saw major reforms around the country that significantly cut down on the prosecution of children as adults, and in some states altogether ended the mandatory adult prosecutions of minors, momentum on that front did not build in 2020. Instead, Missouri adopted a punitive law to expand adult prosecutions and punishments for some minors as young as 14; lawmakers in Missouri who opposed the measure warned that it would primarily harm Black children.

Elsewhere, California adopted a law that will phase out its youth prisons; minors will be detained instead in facilities run by county governments. New Jersey ended fines in the juvenile system.

Policing and law enforcement

In many states, police unions and law enforcement groups successfully lobbied to stop the boldest measures filed in the wake of protests against police brutality in the spring and summer.

In California, for instance, a slate of policing reform bills stalled in the legislature, and then two bills that made it through were vetoed by Governor Gavin Newsom, a Democrat. One would have mandated that district attorneys maintain a list of police officers with a history of lying or misconduct, and the other would have set up a pilot program for mental health or medical professionals to answer some 911 calls. Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker, a Republican, said this month that he would veto a provision meant to mostly ban facial recognition.

But Colorado reached a milestone in June: It adopted a law eliminating qualified immunity, which is the legal doctrine that often shields police officers from civil lawsuits, in state courts.

Colorado’s law, which was introduced by Democratic lawmakers and passed with large bipartisan majorities, also empowers the attorney general to prosecute officers, restricts the standards for use of deadly force, and mandates police departments to disclose more data. Connecticut later limited qualified immunity, with loopholes. Bills to end it in Massachusetts and Virginia seemed in promising shape but died in the legislature.

Another emblematic policing legislation came from New York: In June, the state repealed Section 50-a, a stringent statute that shielded police officers’ disciplinary records. This repeal was a longtime demand of advocates who protested police departments’ ever-expanding use of the statute. Connecticut also expanded transparency over disciplinary records and eased the process to decertify police officers.

Elsewhere, Virginia became the third state to ban no-knock warrants. New York and Connecticut codified special offices to investigate police killings. Minnesota changed police unions’ ability to interfere with an independent arbitrator. Hawaii required police departments to disclose the identity of officers who are discharged or suspended. And some states, including Connecticut, Iowa, Minnesota, and New York, adopted bans against the use of chokeholds and/or neck restraints. But such statutes can be difficult to enforce amid a culture of impunity, as NPR reported.

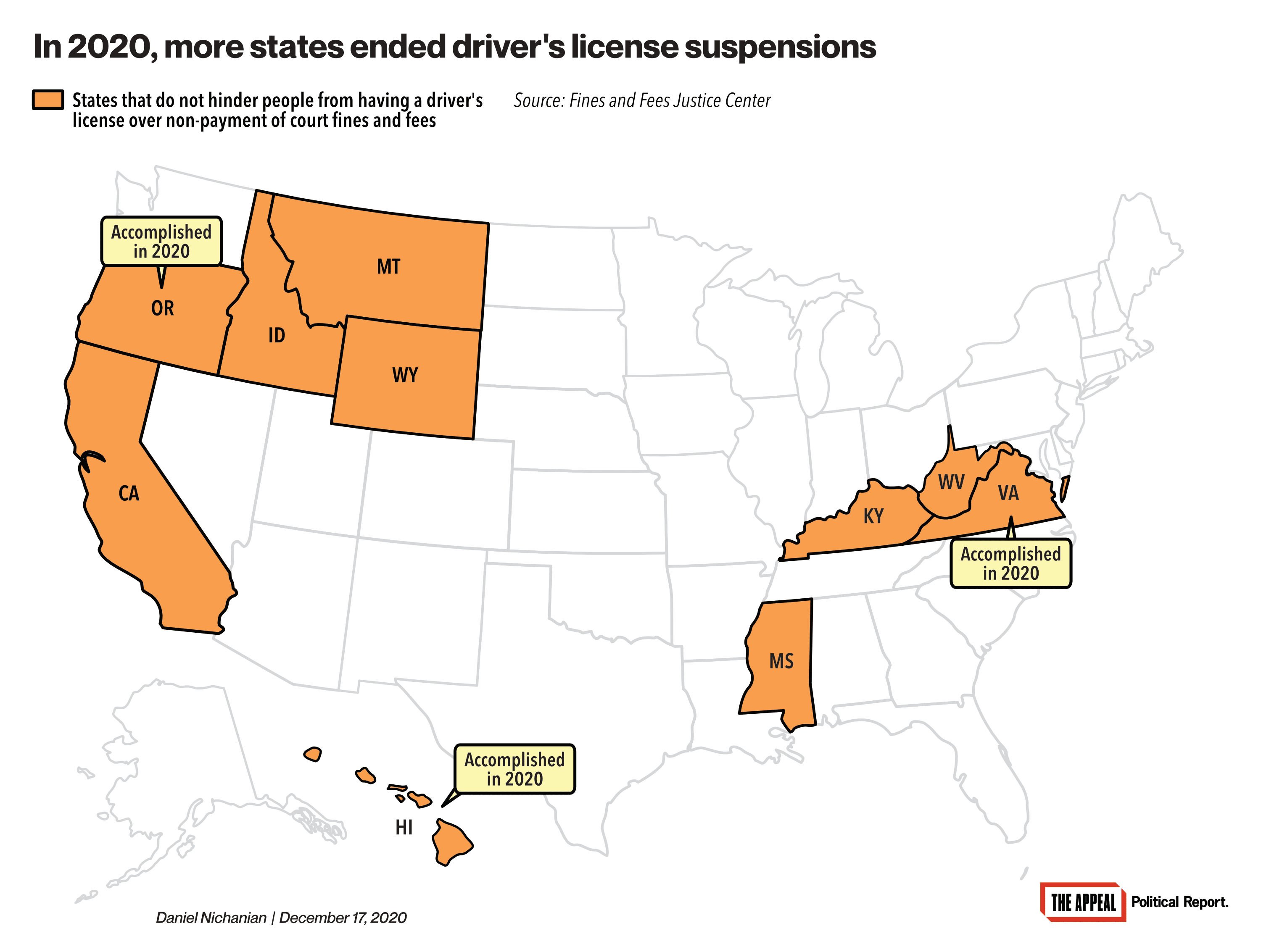

Fines and fees

More states confronted the pervasive practice of suspending drivers’ licenses over court debt. In taking away people’s means of transportation, these suspensions cut off their access to work and make it harder for them to pay off this debt—and those who still use their cars can get prosecuted for it.

Hawaii, Oregon, and Virginia all adopted laws this year to end these suspensions. Overall, this makes 10 states that will not hinder access to licenses over non-payment of fines and fees, according to a national tracker created by the Fines and Fees Justice Center; other states have adopted narrower restrictions on such suspensions, without ending them. (Michigan and New York could still adopt similar reforms before the end of 2020, depending on the fate of bills that remain under consideration.)

These reforms will affect a staggering number of people since suspensions are so widespread. In Virginia alone, more than 900,000 residents were deprived of their licenses over unpaid fines and fees as of 2016, according to a Legal Aid Center lawsuit.

But states could be far more ambitious in stopping the predatory imposition of fines and fees in the first place.

COVID-19 brought the issue into stark relief not only because it has sparked an economic crisis for all, but also because the end of in-person visitations in prisons and jails has compounded the importance of phone and online communication that often cost astronomical prices, as reported this year from Illinois to Alaska and Florida. In October, California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill that would have capped the cost of phone and video calls from prison, and capped the inflation of commissary items; this came a year after he vetoed a different bill that would have required judges to determine people’s financial ability before imposing financial obligations.

But Newsom signed into law a measure to eliminate many administrative fees that are imposed on people by California’s criminal legal system.

Expungement and re-entry

The economic havoc brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic compounded the urgency for states to help people re-enter their communities and lift the barriers of a criminal record. But in some regions, public services closed their doors or could not meet the demands of people released from prison who needed assistance.

And legislation to help was met with a chorus of gubernatorial vetoes.

Maryland Governor Larry Hogan, a Republican, vetoed a bill that would have shielded marijuana convictions from public records. About 200,000 Marylanders stood to benefit. Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves, a Republican, vetoed a bill that would have authorized people to expunge some convictions over nonviolent offenses. And Washington Governor Jay Inslee, a Democrat, vetoed a bill that would have set up a pilot program to automatically expunge some people’s records, citing budgetary constraints.

Michigan bucked that trend in October, when it adopted a major legislative package that could enable hundreds of thousands of Michiganders to clear their criminal records. The package expands the range of cases that people can get expunged, including marijuana-related convictions. It also makes expungement automatic for many misdemeanors and some felonies, though only after a prolonged wait time. Eligible Michiganders will see their records expunged without having to apply or file a petition; the vast majority of people eligible for an expungement do not apply because of cost, lack of information, or administrative complexity.

Michigan is the sixth state to adopt a system to automatically clear convictions, and it will be the most expansive, according to the Collateral Consequences Resource Center. This year, Michigan also eliminated its ban on people receiving food assistance benefits (SNAP) if they have multiple drug-related convictions. .

Other states took some incremental steps to removing barriers for people with past convictions.

North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper, a Democrat, signed an executive order barring employers from asking job applicants whether they have a criminal record, but this will only apply to public sector jobs; broader bills have stalled in the GOP-run legislature. Hawaii expanded partial protections against employment discrimination for people with a criminal record. Kentucky set up automatic expungement for people whose cases are dismissed or who are acquitted. Finally, California adopted a law that loosens the prohibition of formerly incarcerated firefighters becoming civilian firefighters. But the law comes with major hurdles and carve-outs due to the vocal opposition of police unions, state DAs, and firefighters unions.

Pretrial detention

Criminal justice reform advocates in New York had one of the bigger victories in 2019 when Democrats overhauled the state’s bail system to greatly reduce pretrial detention. This reform significantly reduced jail populations in New York starting just before the COVID-19 pandemic, helping contain some of the spread.

Still, law enforcement groups pursued a yearlong crusade against the measure. In March of this year, Democrats chose to partly roll back the 2019 law by expanding the range of circumstances under which judges can impose bail. Some progressive lawmakers, who increased their clout in the year’s legislative elections, opposed the rollback.

After the pandemic began, some states such as Massachusetts and California adopted emergency measures to shrink pretrial detention during the outbreak—meeting longtime demands of advocates to shrink jails and end cash bail, but only on an exceptional basis. Texas took the opposite route when Governor Greg Abbott, a Republican, issued an executive order to block some counties’ efforts to shrink jails to fight the pandemic.

In November, finally, Californians voted to strike down a 2018 law that had eliminated the cash bail system and replaced it with algorithm-driven risk assessments. The bail bond industry opposed the law, and in an unusual twist, so did many advocates who warned that the new system would perpetuate racial disparities in pretrial detention.

Trial procedures and sentencing

California made it harder for prosecutors to exclude Black people from jury pools. As Kyle Barry explains, racial discrimination in jury selection is routine around the country: Prosecutors are not supposed to strike prospective jurors because of their race, but in practice courts allow them to invoke factors that track closely with race—a sleight of hand that California’s new law aims to curtail.

Separate legislation, also signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom in September, will make it easier to appeal a conviction or sentence on the grounds that it is racially discriminatory. And in November, Californians beat back a ballot initiative (Proposition 20) that would have rolled back some decarceral sentencing reforms adopted over the past decade.

Elsewhere, Virginia transferred some sentencing powers to judges to forestall what defense attorneys describe as a “jury penalty,” and Maryland restricted the use of jailhouse informants, Also in Maryland, Governor Larry Hogan’s heated efforts on behalf of punitive measures that would have toughened sentences did not convince the legislature. Oklahoma saw a setback for criminal justice reform when voters rejected State Question 805, which would have prevented prosecutors from seeking harsh sentencing enhancements against some defendants.

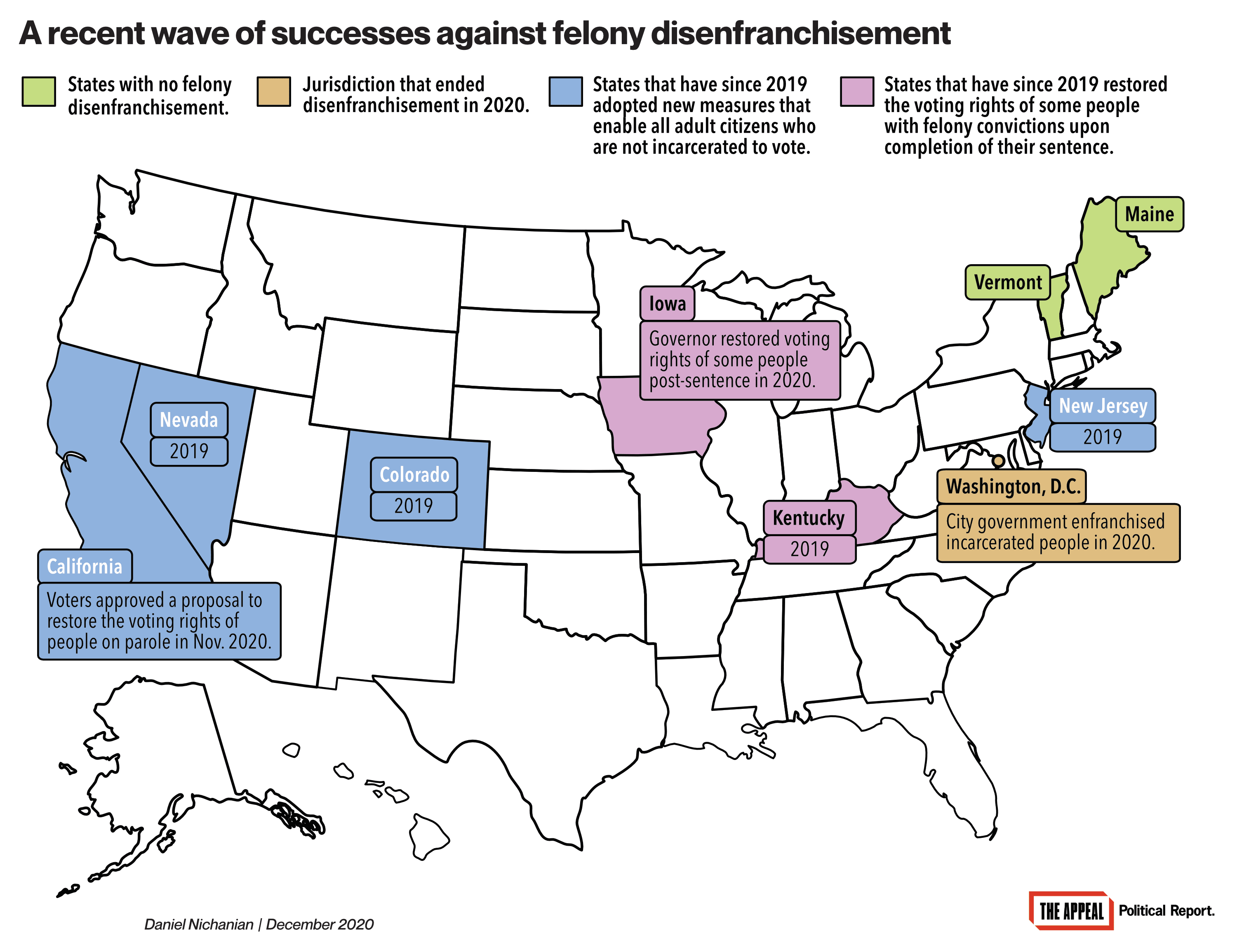

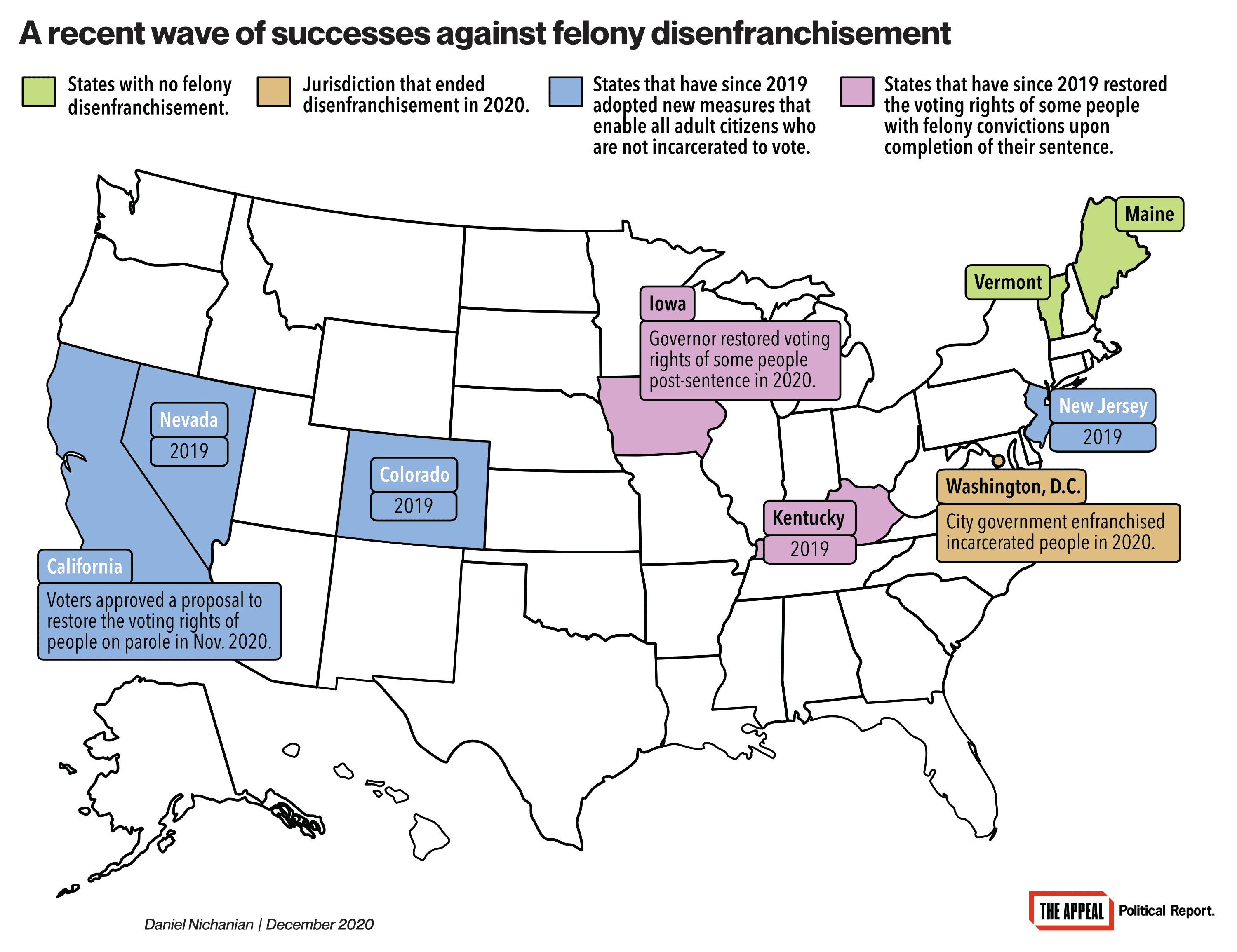

Voting rights and disenfranchisement

Washington, D.C., made history this summer when it eliminated disenfranchisement for anyone with felony convictions, including when they are in prison. It joined Maine and Vermont, which have never barred people from voting because of a criminal conviction.

Elsewhere, though, millions of U.S. citizens were once again barred from voting in this year’s elections. And in the many states that have expanded voter eligibility in recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic stalled outreach efforts and voter registration drives.

Still, some jurisdictions took big steps in loosening disenfranchisement, even if they did so more incrementally than the nation’s capital. California voters overwhelmingly approved Proposition 17 in November, which enfranchised people who are on parole. In practice, the reform means that all voting-age citizens who are not incarcerated will be able to vote. California is the 19th state to adopt such a rule.

Over the summer, amid protests against racial injustice in law enforcement, activists amplified the pressure for Iowa to no longer be the only state in the country to disenfranchise anyone with any felony conviction for life. GOP Governor Kim Reynolds issued an executive order in August that restored the voting rights of most people once they finish a felony sentence. The order affected tens of thousands of people, but also kept Iowa among the nation’s harshest states.

Bills against disenfranchisement did not advance in many other states, including Virginia and Washington State, which have harsh rules by the current standards of Democrat-run states.

Prison gerrymandering

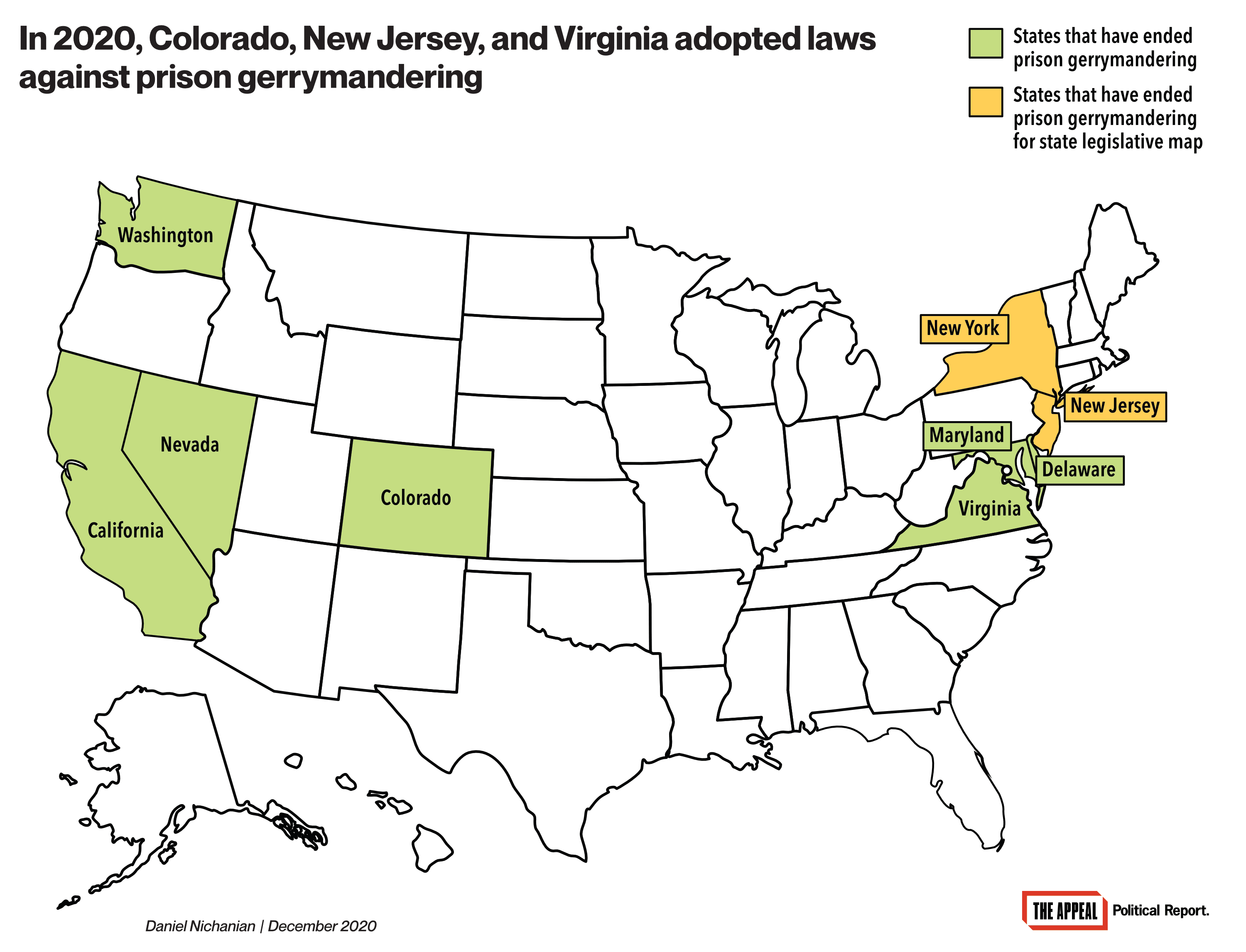

The next round of redistricting is almost upon us, and most states are poised to once again employ prison gerrymandering, the practice of drawing political maps by counting incarcerated people at their prison’s location, rather than at their most recent address. This disproportionately skews political power toward white and rural communities.

The issue has gained political visibility in recent years. In 2020, three states adopted laws to end prison gerrymandering: New Jersey, Colorado, and Virginia. When they redraw some or all of their maps in coming years, they will count incarcerated people at their most recent residence.

“The system is set up to take citizens out of their communities … and increase the political power of [other] communities,” Aaron Greene, associate counsel at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, said after New Jersey’s reform. “Having people counted in the communities where they are from and where they will return, where their families are, is extremely important.”

There are now nine states that have taken legislative action against prison gerrymandering. The clock is ticking for other legislatures to act before redistricting.

And there’s more

Regarding conditions of incarceration: New Jersey made incarcerated people eligible to apply for state aid for higher education programs; California provided that transgender people be detained in a prison based on their gender identity, though the law enables correctional officials to override this; and South Carolina banned shackling women who are pregnant, in labor, or recovering from giving birth. This law also mandates that jails and prisons provide menstrual hygiene products, a reminder of the low bar for state reforms meant to change prison conditions.

Regarding probation: Two states imposed new limits this year on the length of probation terms, which are often interminable, stringent, and can result in incarceration over technical violations. In Minnesota, a notoriously harsh state when it comes to probation terms, the Sentencing Guidelines Commission adopted a presumptive five-year cap, though it comes with carve-outs and will not apply retroactively. And California capped probation terms at one year for misdemeanors and two years for felonies. However, legislative efforts to curtail Pennsylvania’s punitive probation system derailed this year despite some early momentum.

Regarding civil asset forfeiture: New Jersey required that, in some cases, people be convicted before their assets can be seized—a change that falls short of the more comprehensive reform Arkansas adopted last year. Throughout the country, police routinely seize property without trial.

Regarding repression of protests: Tennessee’s GOP-run government toughened penalties for offenses associated with protest activity, part of a wave of recent legislative activity to restrict protests; the new Tenneseee law makes it a felony punishable by up to six years in prison to illegally camp on state property. Florida is considering similar legislation, proposed by Republican Governor Ron DeSantis. And a Georgia law that created a new offense of “bias motivated intimidation” against a police officer was denounced by the ACLU of Georgia “as a direct swipe at Georgians participating in the Black Lives Matter protests.”

Regarding prosecutors: Their often-unchecked clout suffered some setbacks. A California law will enable judges to steer people charged with misdemeanors into pretrial diversion (so completing a program would result in the dismissal of charges) without a prosecutor’s assent. Virginia somewhat narrowed prosecutors’ unilateral ability to transfer children to adult court (see above). Kentuckyians rejected an initiative to extend DAs’ terms to eight years. And, in California and Virginia, importantly for future legislation, cracks began to show in the state associations that lobby on behalf of local prosecutors, often to stymie reforms bills.

Regarding pardons: Nevada voters passed Question 3, a measure that will make the state’s pardon process a bit easier. It ends the governor’s de facto veto power over pardons, and requires the Board of Pardons Commissioners to meet more often to address a backlog of requests.

Finally, regarding immigration: Colorado and New York adopted laws to bar ICE from arresting people who are in or on their way to courthouses, amid a pattern of arrests and detentions. No state adopted new protections for immigrants against local law enforcement cooperating with ICE, even though such sanctuary reforms appeared to have momentum earlier during President Trump’s term. Voters took matters in their own hands by firing some sheriffs who were helping ICE arrest and detain immigrants.