Virginia Makes All Children Eligible for Parole, a Major Shift for This Punitive State

The reform’s impact will hinge on Virginia’s parole board no longer denying most applications it receives.

Daniel Nichanian | February 24, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

The bill’s impact hinges on Virginia’s parole board no longer denying the vast majority of applications it receives.

Virginia will give hundreds of people who have been incarcerated for decades, ever since they were kids, a shot at petitioning for release.

House Bill 35 will make people who have been convicted of an offense committed before the age of 18 eligible for parole after 20 years in prison. The legislature adopted the bill last week and the governor signed it into law today, effective July 1.

In practice, the bill abolishes sentences of life without the possibility of parole for minors; minors sentenced to sentences that amount to life in prison would also get some chance at parole.

“It’s a huge victory,” Heather Renwick, legal director of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, told me. Besides banning life without the possibility of parole for minors, “the bill will provide broader relief and parole eligibility for all kids sentenced in the adult system,” she said.

Still, a major question looms over the concrete effect that the reform would have.

It will only make people eligible to go in front of a parole board, with no guarantee that anyone gets paroled. And the recent history of Virginia’s board is to quasi-systematically deny the applications it receives. This signals the importance of strengthening the parole process alongside reforms that expand eligibility.

HB 35 also will not address the expansive mechanisms that lead minors to be prosecuted as adults in Virginia, and that trigger lengthy sentences in the first place. But the legislature is also considering separate bills to at least narrow those mechanisms.

The proposal was mainly carried by Democrats, including chief sponsors Delegate Joseph Lindsey and Senator Dave Marsden, but it also got GOP support. Seven of the 18 Republican senators who voted supported it.

—

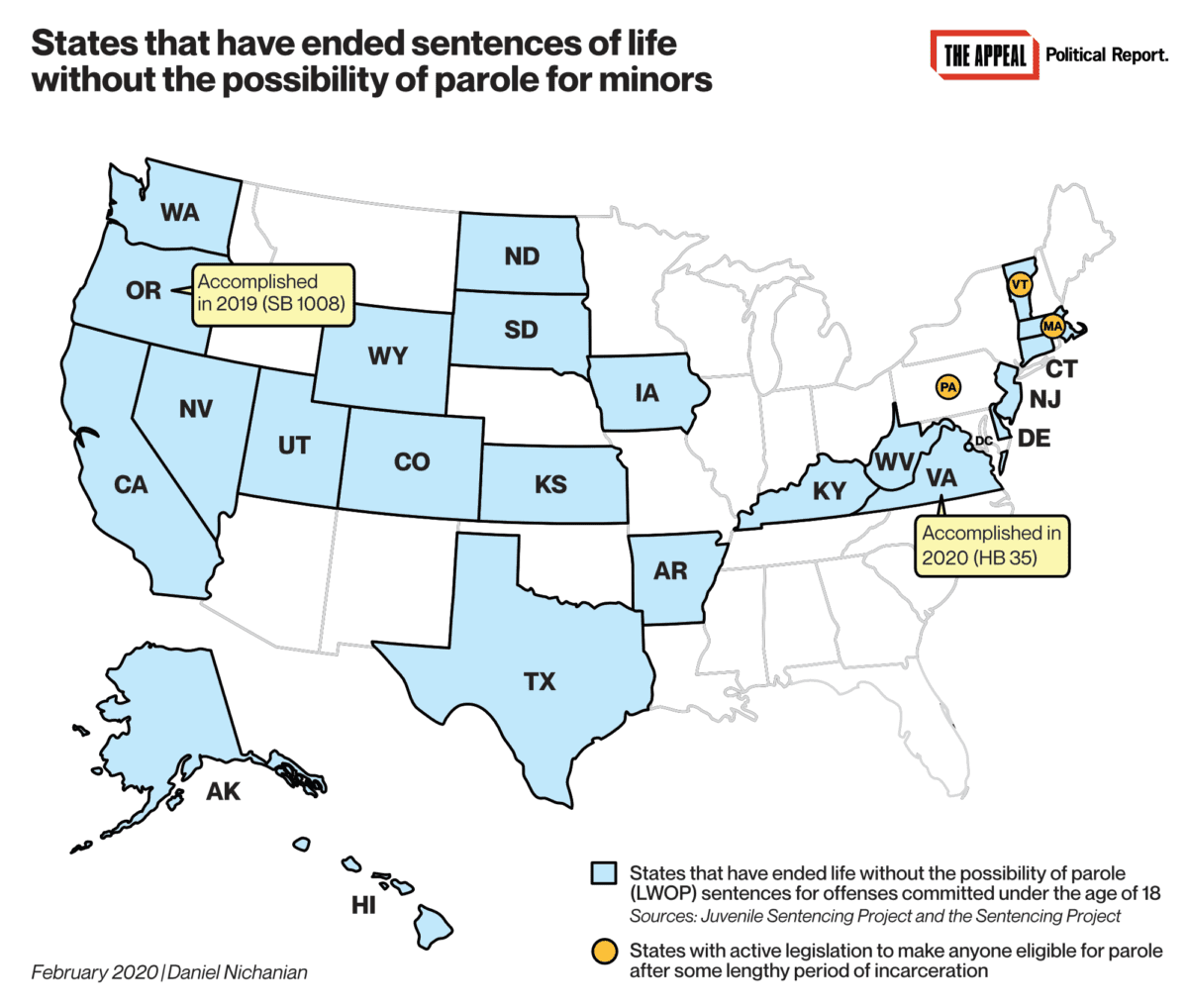

In some ways, this bill is a modest reform. For one, it brings Virginia in line with many of its peers. With HB 35 signed into law, Virginia becomes the 23rd state (plus D.C.) to end sentences of life without the possibility of parole for minors. Oregon passed a similar bill last summer, and such proposals are on the table in other states as well.

HB 35, moreover, is a less expansive change than we’ve seen in other states. When neighboring West Virginia adopted a similar law in 2014, it made minors eligible for parole after 15 years, rather than the 20 that HB 35 stipulates. (Oregon’s law also stipulated 15 years.)

And when Illinois established new parole rules for youths last year, it made people up to age 21 eligible to apply, affirming that considerations of youth do not just stop when someone is a day over 18. HB 35 still sets a cutoff at age 18.

The bill also better aligns Virginia on the U.S. Supreme Court rulings, such as Miller v. Alabama, which ended mandatory life without parole sentences for minors. The state has been slow at granting resentencing, and there is also litigation on whether the other mechanisms that impose extreme sentences on minors are any more constitutional. HB 35 addresses such concerns by retroactively conferring parole eligibility to minors sentenced to de facto life sentences.

When the bill becomes effective, it will affect 720 currently-incarcerated people, according to a legislative analysis.

According to Julie McConnell, a professor of law at the University of Richmond, many minors serve “just as lengthy sentences” as the mandatory life sentences struck down in Miller, and yet their youth is still not adequately considered. “We know so much more about brain development now,” she said. “We know that the brain is not fully developed until 25 or 26. We know juveniles are not necessarily as culpable as adults because they don’t have a sense of long-term consequences, they’re stuck in the environment in which they’re being raised.”

She added of HB 35, “This is a natural extension of what the Supreme Court has said, which is that we should consider the attributes of youth.”

—

This bill’s significance is greatly magnified by Virginia’s exceedingly punitive statutes.

Virginia largely eliminated parole for everyone in 1995, as part of a punitive wave that cut off the ability to obtain early release and considerably increased the length of time people serve.

The state now denies so much as a parole hearing to all but the oldest prisoners. People are only eligible to petition for parole if they were sentenced before 1995, if they were convicted under a youthful offender statute (a label granted to some youth under 21 if their conviction is for a first offense that is not a class 1 felony), or if they qualify for geriatric reasons. As a result, Virginia is one of 16 states graded “F-” in a Prison Policy Initiative review of state parole systems.

This has fueled Virginia’s growing, and aging, prisons. From 1990 to 2015, the prison population more than doubled, while the share of people above age 50 went from to 20 percent from 4.5.

HB 35 and similar bills “are a first attempt to really crack open the idea of bringing parole back to the system,” said Amy Woolard, an attorney and policy coordinator at the Legal Aid Justice Center. “There seems to be a pretty meaningful commitment to looking to bring parole back in the state.” This year, lawmakers filed several broad bills to roll back the 1995 changes and reinstate parole, but they did not move forward. (Even such changes would fall short of proposals around the country to make everyone who is incarcerated at least eligible for parole.) Virginia’s legislature may still commission a review of whether to reinstate parole.

Virginia may also soon pass a bill to make about 300 people sentenced between 1995 (when it ended parole) and 2000 (when it began informing juries of this change) eligible for parole.

—

Expanding eligibility may not by itself change much for anyone, though, including for minors.

That’s because Virginia’s parole board has been denying the vast majority of applications it receives.

According to a Capital News Services analysis of Virginia’s parole board published in December, the vast majority of parole applications are denied: 94 percent since 2014. The rate of denial was above 90 percent for all age groups. Earlier analyses have found similar numbers.

This paints the all-too-common picture of a parole board that routinely, and in many cases yearly, denies the applications of people who have been sitting in prisons for decades.

So would HB 35 provide a “meaningful opportunity for release,” to use the U.S. Supreme Court’s turn of phrase? Or would it mainly provide false hope?

That might depend in part on who gets to sit at the parole table, and on whether the state adopts institutional changes like those advocated by the Prison Policy Initiative to ensure that people receive assistance in preparing for their hearings, and that they are treated fairly by the board.

“Having to pass the hurdle of a parole board is always a gamble, and in the past it has not been a meaningful path,” said Woolard. But she noted Northam’s recent decision to appoint Kemba Smith Pradia, a formerly incarcerated advocate who worked at the ACLU of Virginia, as a sign that attitudes may be changing.

Renwick, of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, called on the Virginia parole board to “reassess its policies and procedures” to take into account “the mitigating attributes of youth” and “the idea that children who commit serious crimes outgrow that antisocial behavior through normal ordinary human development.” The board should “operate under a presumption of release for individuals who went to prison as children barring evidence to the contrary,” she said.

Added Woolard, “There’s optimism, but for those of us who have been advocating on these issues, the proof is in the action.”

Update: The article was originally published on Feb. 21. It was updated on Feb. 24 to reflect the governor’s decision to sign it into law.