How Medicaid Expansion and Criminal Justice Reform Boosted Each Other in 2018

In Georgia, Idaho, and Nebraska, advocates connected the dots between access to care, drug addiction, and mass incarceration.

Daniel Nichanian | November 28, 2018

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

In Georgia, Idaho, and Nebraska, advocates connected the dots between access to care, drug addiction, and mass incarceration.

The Idaho ballot initiative to expand Medicaid got a lift in September when the Idaho Sheriffs Association endorsed it, citing in part the effect it could have in relieving the criminal justice system. “Their endorsement was a big boost to our campaign,” Luke Mayville, a founder of Reclaim Idaho, the group that put this initiative on the ballot, told me. “They’ve seen the extent to which drug addiction problems are interwoven with criminal justice and incarceration, and they believe that the kind of drug treatment and addiction treatment that Medicaid would provide would be an aid to their effort to reduce crime.”

Calls for criminal justice reform and efforts to expand Medicaid boosted one another nationwide during the 2018 campaign.

Stacey Abrams, Georgia Democrats’ gubernatorial nominee, explicitly connected these dots in a detailed criminal justice reform platform that featured the expansion as a core plank. “When individuals receive Medicaid and can finally access mental health and substance abuse treatment in their communities, crime rates drop,” the document states, describing the expansion as “a vital investment in public health and public safety.”

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) significantly expanded Medicaid eligibility for low-income people. But some states have refused to expand the program, depriving millions of the public insurance that the ACA was meant to provide. This harms people released from incarceration. “They most likely will be uninsured because they won’t come out and have a job with employer benefits, and they’re unlikely to be able to afford private insurance,” Robin Rudowitz, an associate director for the Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told me. “Without coverage, those individuals do not have access to affordable, comprehensive medical care.” It also leaves many individuals who experience mental health or addiction issues unable to afford treatment, making them more vulnerable to punitive policies.

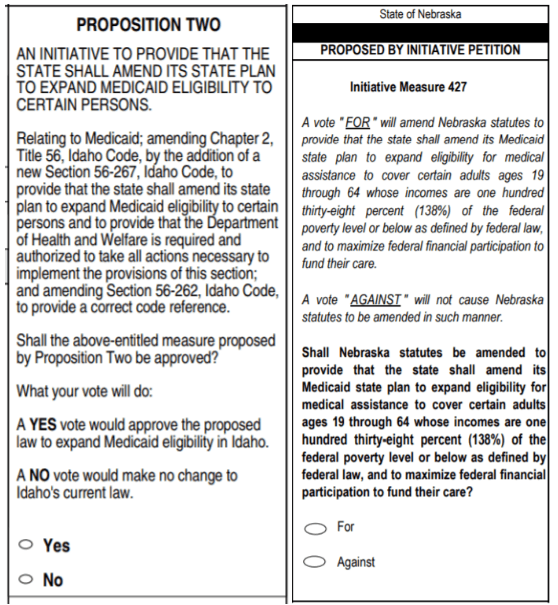

Stacey Abrams fell short in Georgia. But voters in Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah all voted to expand Medicaid via referendums.

Molly McCleery, the deputy director of the health care program of Nebraska Appleseed and an adviser for Nebraska’s expansion campaign, and Mayville both said that criminal justice reform messaging did not feature prominently in their states’ campaigns. But they both also believe that it proved potent with conservative voters worried about the opioid crisis and “the severity of drug addiction,” as Mayville put it.

Mayville recalls encountering criticism that expansion meant providing public benefits to people who are addicted to drugs. “I made the case that far from it being a problem that people on drugs would be on Medicaid, that’s one of the main positives, a tool to fight drug addiction,” Mayville said. “Once I framed it in terms of, we’re trying to give people a way out of addiction, rather than just simply giving benefits to people who are wallowing in addiction, once I framed it as these benefits giving people a way out of addiction and the incarceration that comes with it, I found that to be a good argument.”

Similarly, McCleery told me that the opioid crisis came up during community presentations in Nebraska, and that expansion proponents emphasized the care that Medicaid coverage enables. “One thing people really understand is that if you don’t have insurance you are relying on safety net services, a patchwork of services, and you may not get the full scope of treatment you would get if you had insurance,” McCleery said. She noted that this resonated in rural areas, which have been hit by hospital closures nationwide and in Nebraska.

The successful referendums are just the beginning for Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah. Beyond the questions about how officials will implement them, eligible individuals who interact with the criminal justice system still encounter obstacles to coverage. The Kaiser Family Foundation has released multiple reports on how to facilitate actual access to care, for instance by helping people sign up before they are released or suspending rather than terminating their coverage while they are incarcerated. “The Medicaid expansion created more incentives for states to link [the justice-involved] population to coverage and care,” Rudowitz said.