The Thousands of Local Elections That Will Shape Criminal Justice Policy in 2024

Counties across the nation are electing DAs and sheriffs next year. Bolts guides you through the early hotspots.

Daniel Nichanian | December 12, 2023

Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis’ decision to charge Donald Trump for trying to steal the 2020 presidential race will make Atlanta courtrooms a focal point of next year’s elections. But Willis and Trump could also share a different stage come 2024: They’ll likely appear on the same ballot, as one bids for the White House while the other seeks a second term as Atlanta’s chief prosecutor.

Local DAs like Willis have become a key GOP target this year, as Republicans go after prosecutors who they think are standing in the way of their political or policy ambitions. New laws in Georgia and Texas give courts and state officials more authority to discipline DAs. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, who is challenging Trump for the GOP’s presidential nomination, has over the last 18 months removed two Democratic prosecutors from office, angry over their policies like not prosecuting abortion.

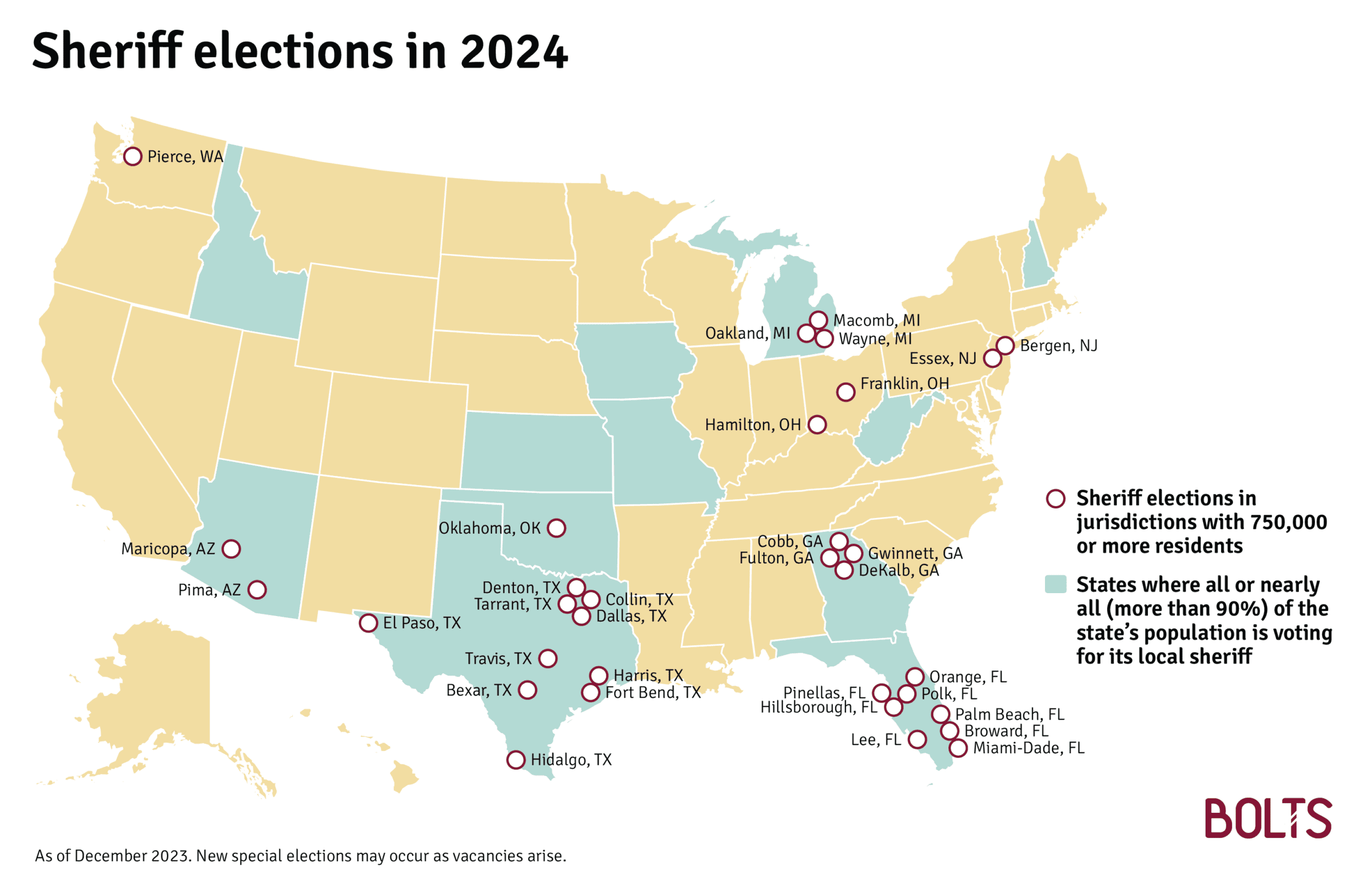

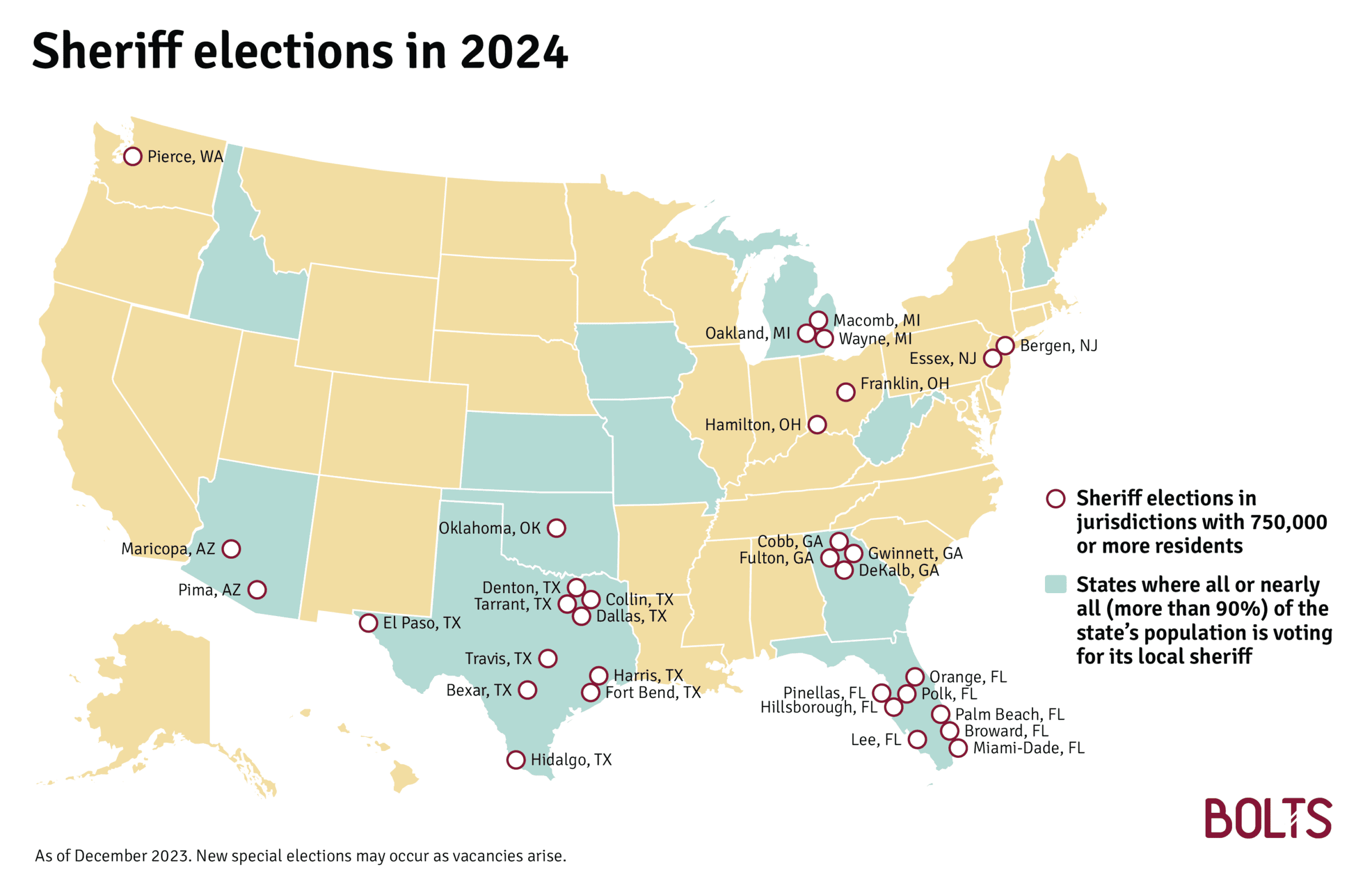

The presidential election is also pulling sheriffs into its orbit. Far-right sheriffs have allied with election deniers, using local law enforcement to amplify Trump’s lies about 2020, ramp up investigations, and even threaten election officials. One such sheriff, Pinal County’s Mark Lamb, is now running for the U.S. Senate in Arizona, leaving his office open. Over in Texas, Tarrant County (Fort Worth) Sheriff Bill Waybourn inspired a new task force that will be policing how people vote while he runs for reelection next year.

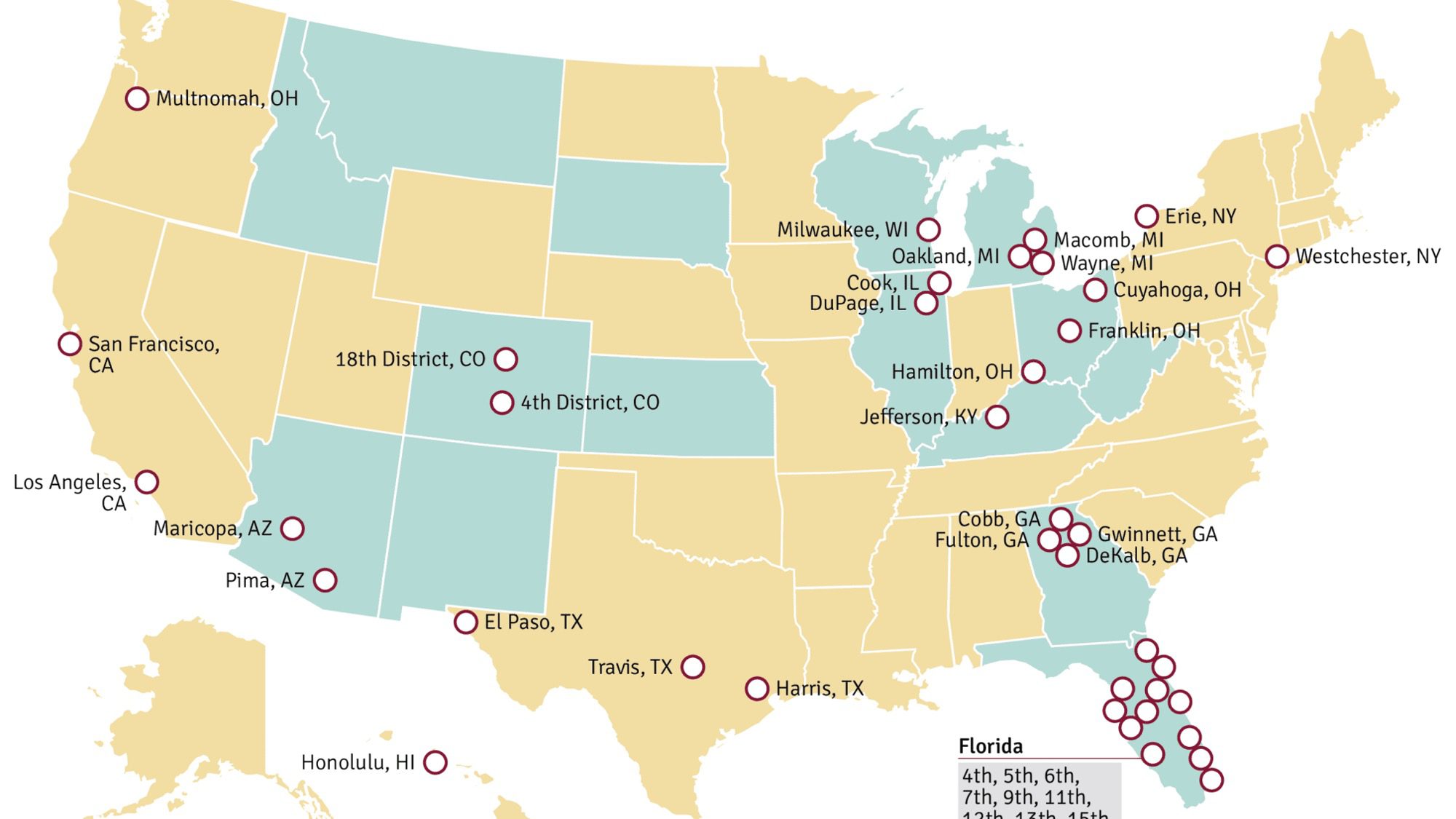

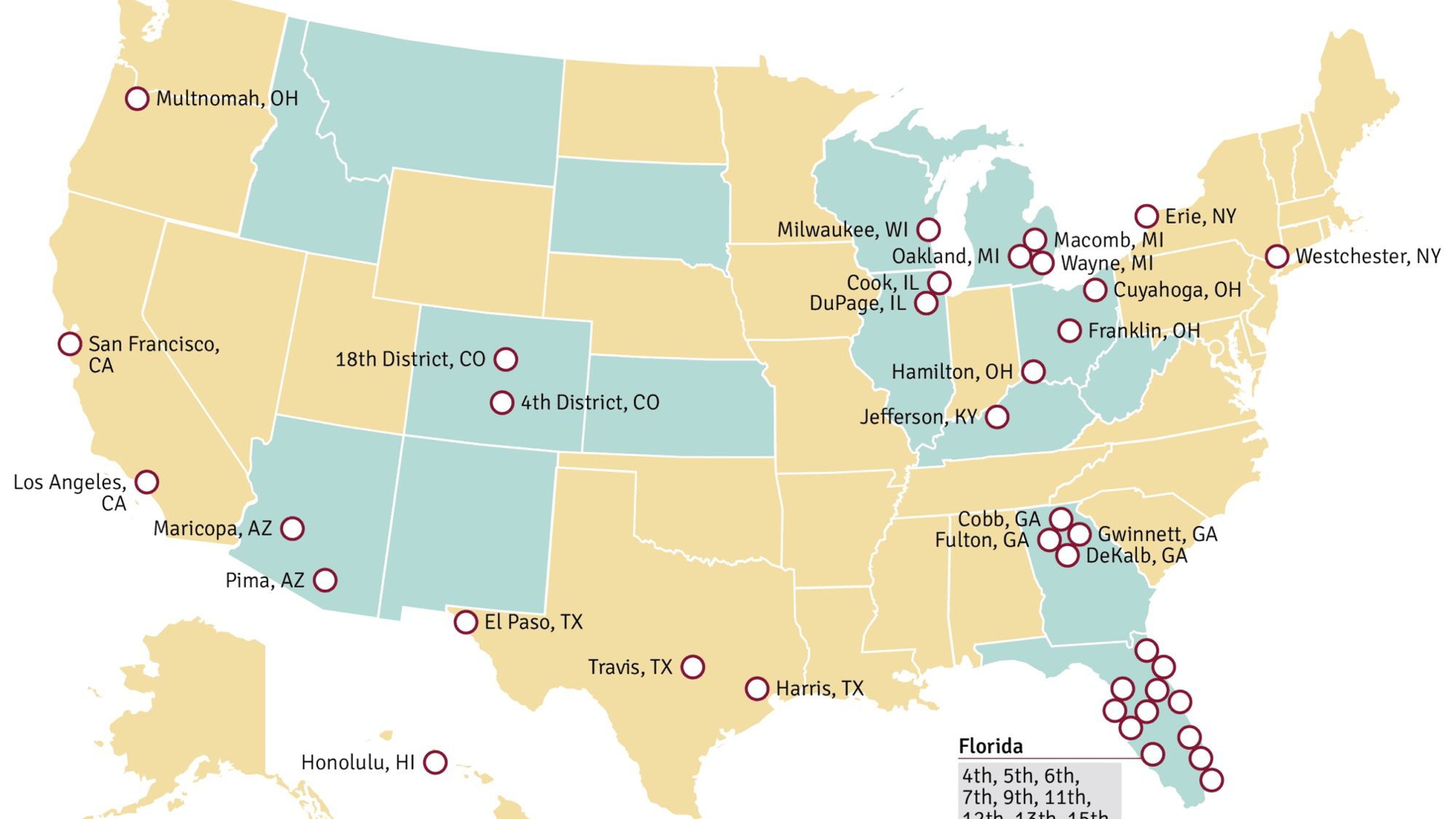

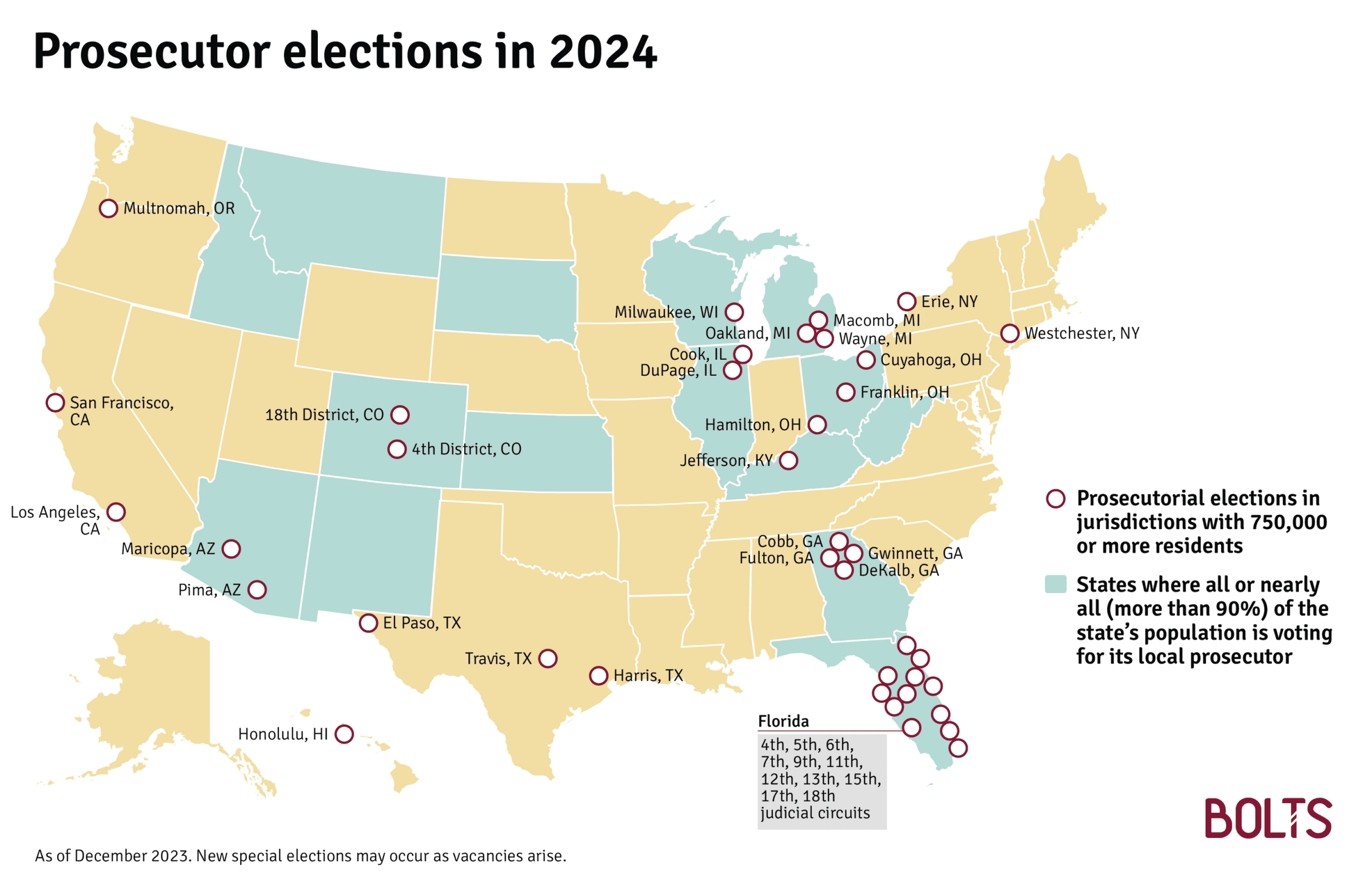

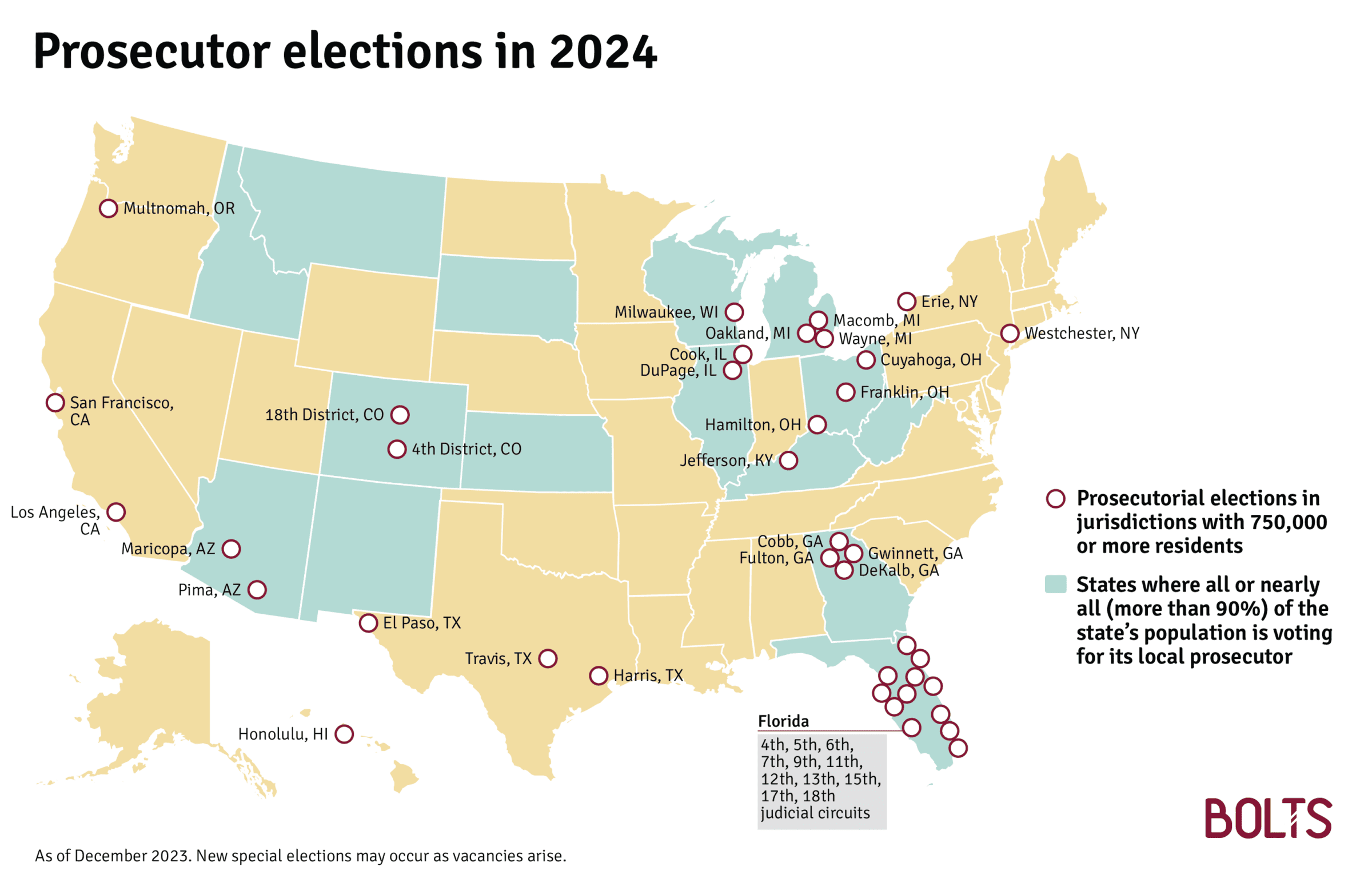

With roughly 2,200 prosecutors and sheriffs on the 2024 ballot, voters will weigh in on county offices throughout the nation next year, settling confrontations over the shape of local criminal legal systems while also choosing the president and Congress.

Bolts today is launching its coverage with our annual overview of which counties will hold such races and when: Find our full list here.

Which Counties Elect Their Prosecutors and Sheriffs in 2024?

These offices often get overshadowed since the criminal legal system is so decentralized, but that’s also what makes these offices so powerful: DAs exert a great deal of discretion within their jurisdiction, choosing what cases to prosecute and how harshly, as do the sheriffs who run their county jails like fiefdoms.

Most of the counties choosing their prosecutors and sheriffs in 2024 last elected these officials in 2020, a tumultuous year defined by the summer’s Black Lives Matter protests and amplified attention to racial injustice.

Many candidates broke the traditional mold of law-and-order campaigning that year, making the case instead that punitive practices haven’t delivered on safety even as they’ve ballooned prisons. Reform-minded prosecutors were elected or reelected in the counties that contain Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, Tucson, and Ann Arbor, among others; voters also elected some new sheriffs who interrupted immigration detention. But progressives fell short in high-profile races in the contain Houston, Detroit, Fort Worth, and Phoenix.

Those offices are all back on the ballot in 2024. Criminal justice reformers are defending more incumbents than ever but also hope to gain some new ground where they’ve faltered in the last cycle, with the future prospect of policies that would ramp incarceration up or down on the line.

To kick off our coverage of criminal justice in 2024’s local elections, here is an early guide to storylines to watch.

1. The reform-minded prosecutors seeking second terms

Los Angeles County’s size (ten million residents) and the tensions around George Gascón’s reelection bid are enough to make LA the marquee DA race of 2024. After Gascón ousted his tough-on-crime predecessor in 2020, he faced an internal revolt from staff prosecutors unwilling to implement his reforms and survived several efforts by his critics to force a recall. (One of the loudest champions for recalling Gascón, Sheriff Alex Villanueva, was ousted by voters in 2022.)

Gascón, who has dubbed himself the “godfather of progressive prosecutors,” now faces a very crowded field to secure a second term. While he’s also faced criticism from the left for not delivering on some of his promises, his opponents are largely running to his right, promising to roll back his sentencing reforms.

Other first-term progressive incumbents are also up for reelection. They include former labor organizer José Garza in Texas’ Travis County (Austin), Eli Savit in Michigan’s Washtenaw County (Ann Arbor), Deborah Gonzalez in Georgia’s Clarke County (Athens), and Laura Conover, who went from protesting the death penalty as a youth activist to promising to never seek it as the chief prosecutor of Pima County (Tucson).

Police groups have taken note and are already involved in these races. In Austin, police groups have tried to drum up complaints against Garza, who used his first term to prosecute police officers accused of violence, breaking with usual norms of impunity in a way that has made him a target for the national right. Last week, though, Garza dismissed the felony assault charges he had brought against 17 officers for their actions against protesters in 2020.

Other new prosecutors who’ve clashed with police include Mike Schmidt in Oregon’s Multnomah County (Portland), whose challenger Nathan Vasquez has a closer relationship with the police, and Mimi Rocah in New York’s Westchester County. Rocah, who won her DA race in the wake of a major police scandal, vacated convictions that were tied to the testimony of a disgraced police officer. She won’t seek reelection next year, sparking an open race.

2. Clashing visions of public safety

Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx is retiring in 2024, eight years after ousting Chicago’s chief prosecutor and starting to implement some reforms. So far, the Democrats running to replace her are walking a line between promising to keep Foxx’s changes and vowing to work more closely with law enforcement; a GOP candidate, meanwhile, has denounced Foxx for turning the office into a “social service agency instead of the prosecuting arm of the people.”

However hyperbolic, that statement underscores the clashing visions of public safety in many of these prosecutorial races. Reform-minded candidates often make the case for strengthening a broader array of public services as an answer to crime, while their critics want to keep the focus on the more conventional tools of policing and incarceration.

In Ohio’s Hamilton County (Cincinnati), for instance, Republican incumbent Melissa Powers hopes to prevail in a county that’s trending leftward by stroking fears about the effects of a Democratic takeover. She recently said her loss would turn Hamilton County into “a Baltimore, a Saint Louis,” naming two of the nation’s big cities with the highest share of Black residents. To prevail in November, Powers would need to perform strongly in the county’s populous suburban areas, which are far whiter than its urban core of Cincinnati.

But many of next year’s most intriguing elections will be decided within the Democratic Party. Incumbents with a record of fighting local criminal justice reforms, and who beat back progressive challengers in 2020 or 2022, may choose to seek new terms in 2024.

These incumbents include: San Francisco DA Brooke Jenkins, who has embraced harsher policies and dropped police prosecutions since replacing Chesa Boudin, a progressive who was recalled in 2022; Harris County (Houston) DA Kim Ogg, a fierce critic of local bail reforms whose clashes with reform-minded Democrats have escalated this year; Cuyahoga County (Cleveland) Prosecutor Michael O’Malley, known for the frequency with which he seeks death sentences; Wayne County (Detroit) Prosecutor Kym Worthy, who has defended punitive practices toward minors; and Albany County DA David Soares, who is a leading voice among New Yorkers demanding more rollbacks to the state’s recent bail reforms.

Some of these races will be slow to take shape since the filing deadlines are still months away. But in Houston and Cleveland, the primaries are already around the corner. On March 5, Ogg faces Sean Teare, a former prosecutor in her office whose platform is more muted than some of Ogg’s prior opponents but who has support from some of her progressive critics. On March 19, O’Malley faces law professor and former public defender Matthew Ahn, who has pledged to never seek the death penalty and decrease pretrial detention.

Bolts will keep an eye on these and many more races next year, with prosecutor elections still taking shape all around the nation, from Bernalillo County (Albuquerque) and Maricopa County (Phoenix) to Milwaukee and Honolulu.

3. Can criminal justice reformers even run for local prosecutor in certain red states?

When DeSantis suspended Tampa prosecutor Andrew Warren over policy disagreements in 2022, Bolts writer Piper French pondered how to take future Florida elections seriously in light of that abrupt move. “What does it even mean to run for office when the governor’s political whims could turn a win into a loss?” she asked. Since then, Warren’s DeSantis-appointed replacement has rolled back some of his reforms, and DeSantis has since fired a second prosecutor, Monique Worrell, in Orlando. (Worell is still contesting her ouster in state court.)

Nearly all Floridians will vote on their prosecutor in 2024. That means that in Hillsborough (Tampa) and Orange (Orlando) counties, residents will get to weigh in for the first time since DeSantis summarily dismissed the officials they’d elected in their last local elections.

But the atmosphere created by DeSantis will make it tricky for there to be real policy choice in those elections. In Tampa, Orlando, and everywhere else in the state, candidates will know that their win may be overturned by the governor if they run on a vision that differs from his.

A similar dynamic exists, to a lesser extent, in Georgia, where the GOP adopted a new law that makes it a removable offense for local DAs to propose certain policies that progressives have prized, as well as in Texas, where some DAs are facing similar efforts to oust them. Conservative critics of Garza, Austin’s DA, filed a complaint seeking to remove him from office this month over his approach to prosecuting lower-level offenses.

4. Who will speak up against gruesome jail conditions?

Aggravated by routinely poor health care, jail deaths are a crisis all over the country—including in states such as Georgia, Michigan, Texas, and West Virginia that will be electing all of their sheriffs in 2024.

Sheriff Bill Waybourn, for instance, has overseen a startling string of deaths in Tarrant County, Texas, though that didn’t stop the Republican incumbent from narrowly securing reelection in 2020.

Patrick Moses, one of Waybourn’s two Democratic challengers next year, promised to step up investigations into jail deaths when he launched his bid last week. “I view the 60 in-custody deaths at the Tarrant County Jail since 2018 as 60 individual reasons to run for office,” he says on his new website.

Other counties with sheriff races are under investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice for conditions in their local jails, including Fulton County (Atlanta) and parts of South Carolina.

Fulton County Sheriff Pat Labat, a Democrat, is facing heavy fire and calls for his resignation due the many people who’ve died under his custody in Atlanta and due to his flailing response. Asked by Atlanta News First last week if Labat should step down, the chair of the county board pointed to the upcoming elections: “In the final analysis, it’ll be up to the voters come 2024.”

5. The rise of the far-right sheriffs

After Kansas’ most populous county, Johnson County, voted for Joe Biden by eight percentage points in 2020, Republican Sheriff Calvin Hayden went on a crusade claiming that elections are marred by widespread fraud and ramping up investigations, echoing Trumpian conspiracies.

Hayden is just one of the many sheriffs who have linked up with election deniers and other far-right organizations, using the power of the badge to push their agenda. And now he’s already facing an opponent in what’s likely to be a tough reelection bid next year.

Many sheriffs with similar politics represent far redder territory, though recent examples show they may still lose against fellow Republicans or independents. The GOP primary to replace Mark Lamb in conservative Pinal County will be especially noteworthy if it yields a new sheriff who won’t see his role as propping up so-called constitutional sheriffs all around the nation.

6. Immigrants’ rights will define more sheriff elections

Several Southern counties in 2020 interrupted their history of anti-immigration policies. In Charleston County, South Carolina, and Cobb and Gwinnett counties, Georgia, voters elected Democratic sheriffs who terminated their counties’ so-called 287(g) contracts—agreements with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) that authorizes sheriff’s deputies to arrest and detain people they suspect to be undocumented immigrants.

These sheriffs are all up for reelection in 2024, all in counties that may be competitive in a general election.

It may be hard for immigrants’ rights activists to break up more of these contracts through the polling booth in 2024, though. Per Bolts’ analysis, there are almost 90 counties presently in the 287(g) program that hold sheriff’s races, but they’re mostly in staunchly conservative areas. The exceptions are largely in Florida, due to a recent law signed by DeSantis that mandates that sheriffs join 287(g) whatever their own preferences. Outside of Florida, only one Biden-carried county has a 287(g) contract and is voting for sheriff in 2024: Bill Waybourn’s Tarrant County.

But collaboration with ICE extends far beyond 287(g). Many sheriffs rent out jail space to ICE, or seek out federal grants to police immigrants. And come 2024, sheriff races in Arizona—a border state with a long history of anti-immigrant practices—may be the central battleground for those debates, especially with yet another unpredictable election taking shape in Maricopa County.

Home to Joe Arpaio, one of the nation’s most visible far-right politicians, Maricopa County in 2016 saw Democrat Paul Penzone oust Arpaio and end some of the county’s most aggressive practices against immigrants. But Penzone also severely disappointed immigrants’ rights activists by maintaining close ties with ICE and keeping federal agents in his local jails.

Penzone announced this fall that he’ll resign in January, making the race unpredictable at this stage. In early 2024, the county board will need to replace him with a new Democrat, who’d then decide whether to seek reelection; already in the running is Penzone’s 2020 Republican rival, Jerry Sheridan, a former Arpaio deputy. In this county of 4.4 million, the race may present an opportunity for local immigrants’ rights activists to gain a stronger ally, though it also opens the door for one of the nation’s largest law enforcement agencies to swing back to the far right.

7. The many other elections that will matter greatly for criminal justice policy

Sheriffs and prosecutors are just slices of the vast institutional edifice that runs the nation’s criminal legal systems. In 2024, big cities such as Baltimore and San Francisco will elect their mayor—an office that often, though not always, exerts direct control over the police department.

Ten states will elect their attorneys general, a role with broad authority over law enforcement. At least 33 will elect supreme court justices, who’ll shape local policy and individual criminal cases.

And all of these races are bound to be overshadowed by a presidential campaign likely to pit President Biden against his predecessor. Trump is again playing up a strongman image, proposing the death penalty over drug sales and outlining a vast deportation infrastructure for which the collaboration of local sheriffs could prove critical.

Stay up-to-date

Now is the best time to support Bolts

NewsMatch is matching all donations (up to $1,000) through the end of the year. Support our nonprofit newsroom today.