When New Jersey Next Redistricts, It Will Count Incarcerated People Where They Lived

A new law ends prison gerrymandering in legislative redistricting. New Jersey will continue to disenfranchise incarcerated people.

Daniel Nichanian | January 21, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

A new law ends prison gerrymandering in legislative redistricting. New Jersey will continue to disenfranchise incarcerated people.

Most states draw political maps by counting incarcerated people at their prison’s location, rather than at their most recent address. Known as prison gerrymandering, this practice shifts political power from cities and more diverse communities, which suffer the brunt of mass incarceration, to the disproportionately white and rural areas where prisons are often located.

New Jersey is ending prison gerrymandering in legislative redistricting, the seventh state to do so.

Governor Phil Murphy will sign Senate Bill 758 into law on Tuesday morning, his office has told the Political Report. The legislature passed the bill last week.

SB 758 provides that, when New Jersey redraws its legislative districts next year, it will count incarcerated people at their most recent residence.

“Today New Jersey puts an end to the process of unfairly skewing districts and the resulting imbalances in our state representation,” said State Senator Nilsa Cruz-Perez, a Democrat, in a press release sent out by Murphy’s office.

The racial skew caused by prison gerrymandering has been acute in New Jersey. The practice, which draws comparisons to the Three-Fifth Clause, has reduced the political representation of counties like Camden and Essex (home to Newark), where a disproportionate share of the people New Jersey incarcerates is from, according to statistics by the Prison Policy Initiative.

“You have citizens from all over New Jersey, like from Essex County, that are put in counties like Cumberland County, which has three prisons,” Aaron Greene, associate counsel at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, told the Political Report. “It shows how the system is set up to take citizens out of their communities… and increase the political power of [other] communities. They are just bodies counted. Legislators don’t consider them citizens but they play a role in their political power.” He added, “Having people counted in the communities where they are from and where they will return, where their families are, is extremely important.”

Greene emphasized that the reform is a “first step,” though. “We also don’t forget that these citizens still don’t have the right to vote,” he said. “I don’t think anyone should be counted as just a body. They should be able to have a basic human right to participate in the civic parts of our society.”

Last month, New Jersey restored the voting rights of people who are on parole and on probation, a move that affects more than 80,000 people.

But New Jersey will continue to bar people from voting if they are incarcerated over a felony conviction. This means that its prison system’s record racial inequality will continue to resonate in its elections. African Americans make up a majority of the people incarcerated in New Jersey, and so of the people who will be disenfranchised going forward; only 13 percent of New Jersey’s population is Black.

Another limitation of the new law is that it only applies to the process of redrawing maps for the state legislature. Prison gerrymandering will perdure for congressional redistricting, and for the drawing of most local districts like city council wards. Its effects are far less pronounced at the congressional level than the legislative one, since the prison population represents a far smaller share of a congressional district’s population. Still, most other states that have adopted legislation against prison gerrymandering addressed congressional redistricting as well.

On Tuesday, Murphy also signed legislation that enables enabling all eligible voters to register to vote online.

The state can go further in easing if not automating the process by which people who interact with the criminal legal system register to vote. Ryan Haygood, president of the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, told the Political Report in December that he would like to see the state “set up regulations that make probation and parole officers agencies that register folks. When they interact with those agencies, those agencies should register them: they should tell them they’re eligible to register and they should help them register.” He added, “We got a fair amount of work to make sure the state is doing its part to notify people and helping them register.”

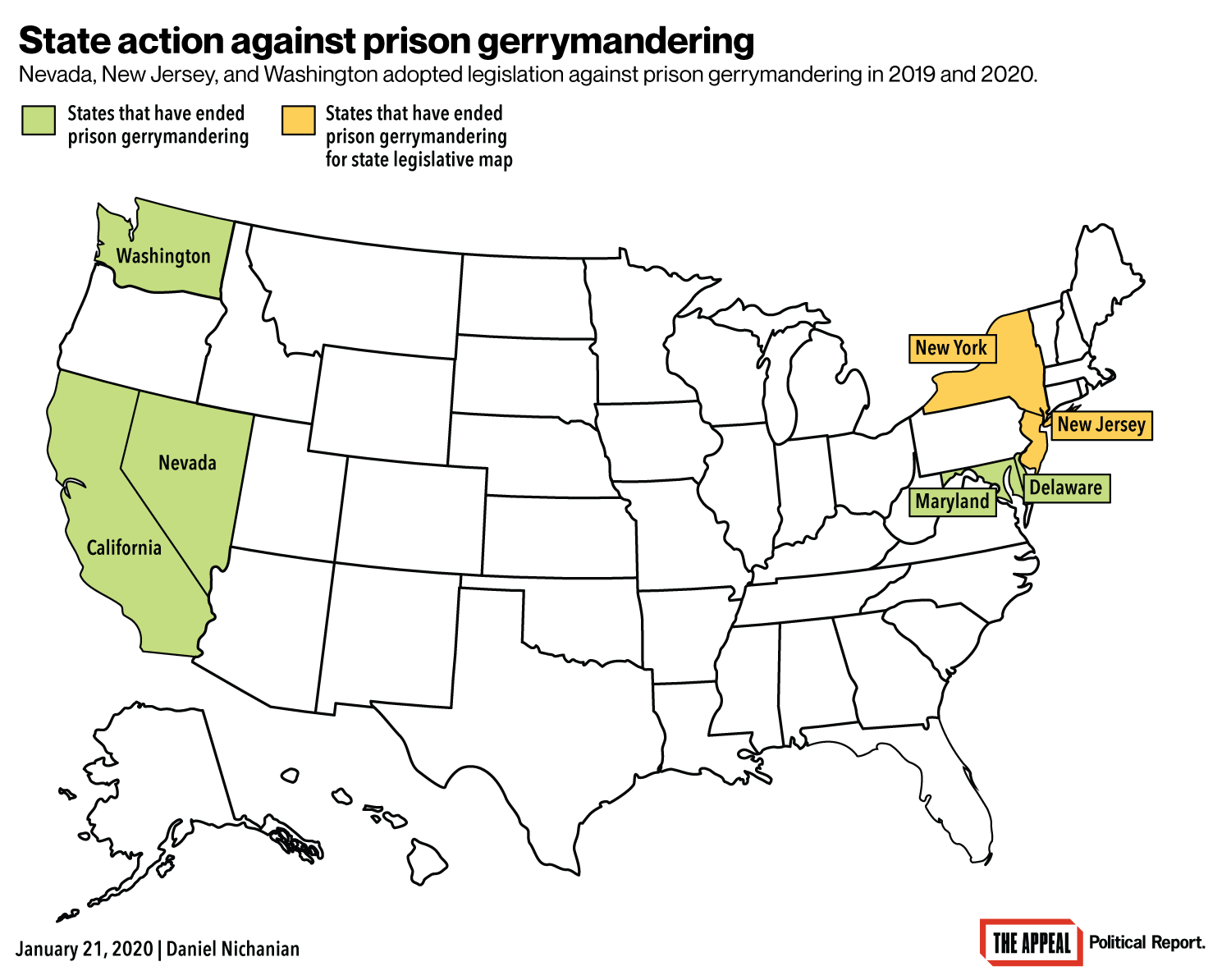

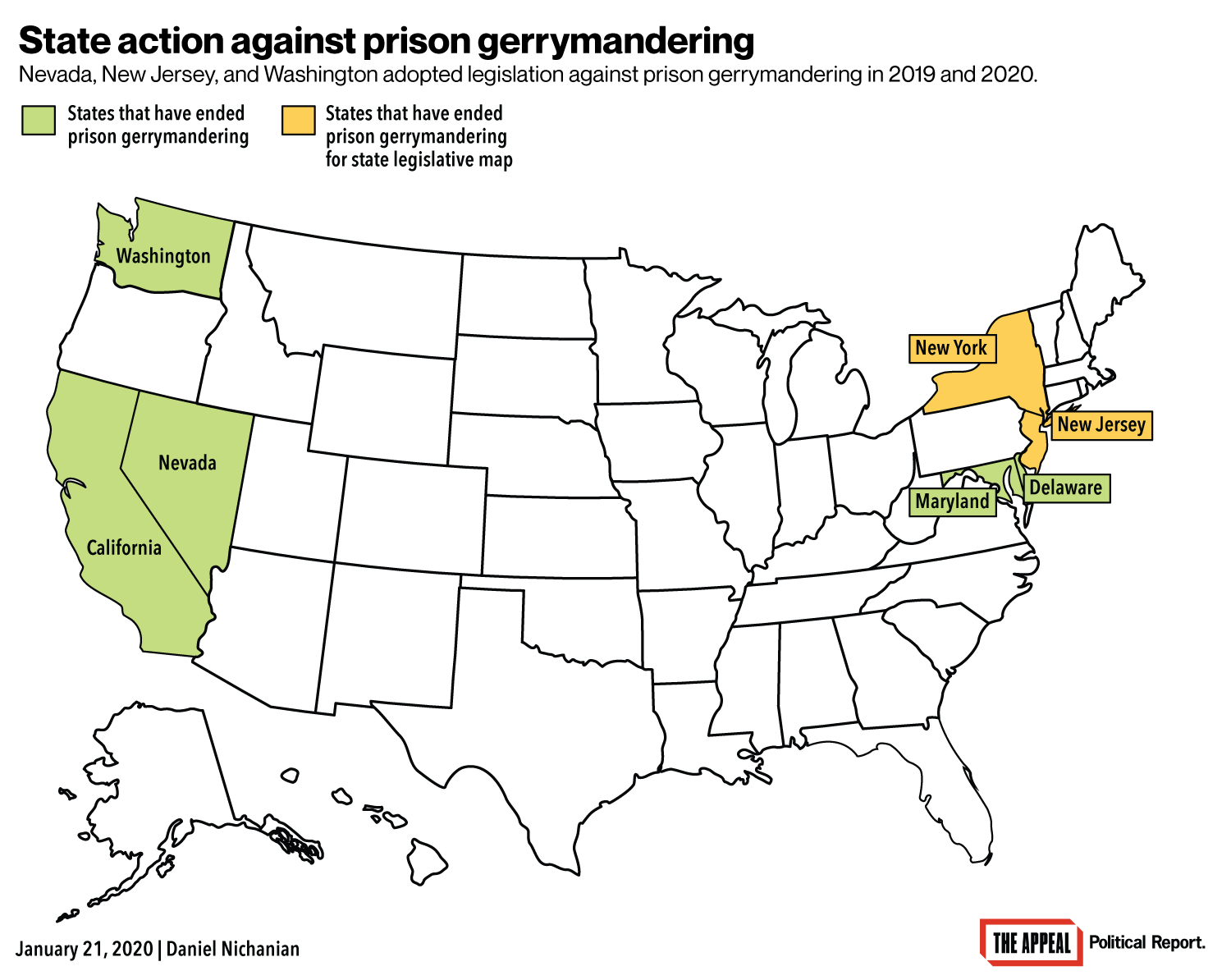

With its new law, New Jersey joins California, Delaware, Maryland, Nevada, New York, and Washington as the only states to have reformed prison gerrymandering. Nevada and Washington did so in the spring of 2019.

Preparing for 2020, lawmakers have filed new legislation against prison gerrymandering in Colorado and Virginia; bills were introduced but did not make it out of committee last year in at least Connecticut, Illinois, Oregon, and Rhode Island. All these states are governed by Democrats. (Other states run by Democrats, or where Democrats have veto-proof majorities, are Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Mexico and Vermont.) Some lawmakers who represent districts that contain prisons resist change, arguing that it would be unfair to their constituents.

The clock is ticking if states are to act in time for the next round of redistricting.

In its upcoming decennial census, the Census Bureau will count incarcerated people where they are imprisoned. Advocates had called for a change to this convention to bring a federal end to prison gerrymandering, but the agency rejected their demands. This left reform to states. New Jersey’s law instructs the Department of Corrections to create adjusted databases out of the census: Subtract incarcerated people from the population count of the place where they are detained and add them to the population count of the place they resided beforehand. (For people with out-of-state addresses, the New Jersey DOC will only complete the first step.)

“There is still plenty of time left for states to pass reforms,” Aleks Kajstura, the legal director of the Prison Policy Initiative, told the Political Report in July, pointing to late 2020 if not 2021 as a horizon. “That said, the sooner the better, particularly to allow for a smooth process for the transfer of data between the Department of Corrections and redistricting authorities.”