In San Francisco, “No Intention to Seek Justice”

Internal emails, interviews with former DA staff, and the recent treatment of certain victim families show how Chesa Boudin’s recall and Brooke Jenkins’s early decisions disrupted the city’s most sensitive and rarely-prosecuted cases—police killings.

Piper French | November 5, 2022

San Francisco police shot Sean Moore, a Black man suffering from schizophrenia, right outside his own home. He died three years later of his injuries. Police say they opened fire on Luis Góngora Pat, an unhoused Mayan Mexican man, because he was threatening them with a knife, but multiple eyewitnesses reported that he was sitting on the ground and far from officers when they started shooting—first with bean bag rounds, and then real bullets. A rookie officer who suspected Keita O’Neil, another unarmed Black man, of car theft shot and killed him the moment he exited the vehicle he was in and started to flee.

These are three of the police killings the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office tried to prosecute under Chesa Boudin, who was elected in 2019 on promises of reform that included greater police accountability. Less than a year after he took office, Boudin bucked the longstanding trend of clearing killer cops and filed manslaughter and assault charges against Christopher Samayoa, the officer who shot O’Neil, heralding the case as “historic” and calling it the first known prosecution for an on-duty police homicide in the city’s history.

April Green, O’Neil’s aunt, wants justice for her nephew’s death. “My nephew is not coming back,” Green told me. “But there’s a lot of other kids that are being murdered by police unjustly. He’s not the first and he won’t be the last. The only difference is we have a video.” Green also hopes the case sets an example. “This case will set a precedent for future cases that involve police that abuse their power,” she said. “It will show that police can be held accountable too … I think it’s very important to show that.”

But if Green’s family ever sees justice, it will be a long road. Police killed O’Neil in 2017, a year after former DA George Gascón created a new division inside his office, the Independent Investigations Bureau (IIB), to evaluate instances of police violence and determine whether to prosecute officers. This bureau’s agreement with the San Francisco Police Department, signed in 2019, signaled a sea change: before, police had always led investigations of their own. But Gascón’s IIB never filed charges against an officer for killing someone. Boudin, his successor, revamped the bureau to include attorneys with homicide experience. Boudin’s IIB was pursuing charges against several cops, including the one who killed O’Neil, and investigating dozens of other cases.

Then, this summer, the ground shifted again. Boudin was ousted in June in a recall election organized by critics who accused him of endangering public safety. Mayor London Breed, who frequently clashed with Boudin, appointed Brooke Jenkins, a prominent surrogate for the recall effort, as the new DA.

Jenkins has spoken often about the importance of securing justice for victims, recently tweeting, “Justice delayed is justice denied.” She has professed that she is “dedicated” to police accountability, and has said that cops who break the law should be prosecuted accordingly.

But internal emails I obtained under California open records law and interviews with former IIB staff show that the bureau tasked with holding San Francisco police accountable has been beset by disruption and dysfunction since Boudin’s recall.

Within two months of her appointment, Jenkins had fired or removed all three lawyers working cases on the IIB under Boudin; as of early November, only two lawyers had joined the unit to replace them. The emails reveal that the attorney Jenkins put in charge of the bureau has called the IIB’s work under Boudin “deeply corrupted,” began a “serious review” of police violence cases prioritized under the previous DA, and treated an outgoing lawyer in the bureau like a security threat instead of seeking help transferring complex and sensitive cases to the next administration. The new head of the IIB has accused the previous staff of incompetence and serious breaches of ethics, and criticized their work as being guided by “the political whims of former leaders”—echoing the charge frequently levied by the lawyers defending the police officers charged by Boudin.

After cleaning house and declining to consult with previous IIB staff, the current IIB has cited its unfamiliarity with ongoing police prosecutions as a justification for delaying hearings in the active cases, which have been moved until after the special election set to take place on Nov. 8 to fill the remainder of Boudin’s term. Jenkins faces three opponents, including Joe Alioto Veronese and John Hamasaki. Both are former members of San Francisco’s civilian Police Commission, charged with oversight over the department, and both have taken issue with her handling of the IIB.

“The police union has a very dedicated and passionate interest in ensuring that none of their members face accountability,” Hamasaki, a frequent critic of the city’ police department, told me. “Anything outside of kid gloves is seen as antagonistic by the police,” he said, describing a dynamic that played out in other DA races in the region this year.

Hamasaki added that Jenkins’s IIB has “sent a pretty clear message that they are going to back the police union, regardless of whether or not its members are committing crimes…what it suggests very strongly is that they believe that there’s one law for the rest of us and one law for the police.”

One of the central promises of the reform prosecution movement has been to institute meaningful scrutiny and accountability for police who kill civilians. But Boudin’s attempts to do so, and the apparent rollback under Jenkins, show the challenges of investigating law enforcement killings when police unions interpret any challenge as a declaration of war.

The first case against an officer that Boudin’s IIB brought to trial ultimately ended in acrimony and an acquittal, with accusations of misconduct on both sides. The case infuriated San Francisco’s powerful police officers’ association, and caused the police chief to temporarily back out of an agreement between the San Francisco Police Department and the DA’s office that governs IIB’s work after the threat of a vote of no confidence from his department.

Jenkins has cited the successful renegotiation of the agreement as evidence of a restoration of harmony between the two. She has publicly stated her desire to “repair” the DA’s relationship with the police department, and it appears that police are already reversing course on what many decried as a “work stoppage” under Boudin.

The uncertainty now hanging over the IIB cases is a fresh wound for families who have been waiting years for some form of justice. “I’m really worried that if Jenkins wins this election, that officer’s going to walk away with murdering my nephew,” Green said. “It’s no doubt in my mind.”

“We never stop hoping for justice”

Gascón’s IIB had declined to charge the officers who killed Luis Góngora Pat, Michael Mellone and Nathaniel Steger, but Boudin decided to reopen the case for investigation. For the Góngora family, Boudin’s decision to reconsider the case represented the first glimmer of hope that they might receive some measure of justice since 2016, when the shooting occurred.

“We don’t have high expectations for elected officials,” said Adriana Camarena, a lawyer and Góngara family friend who has served as an informal advocate and spokesperson. “But we believed they were being earnest and truthful to us rather than just political…we never stop hoping for justice, and to clear the good name of your family members that the police has just run through dirt.”

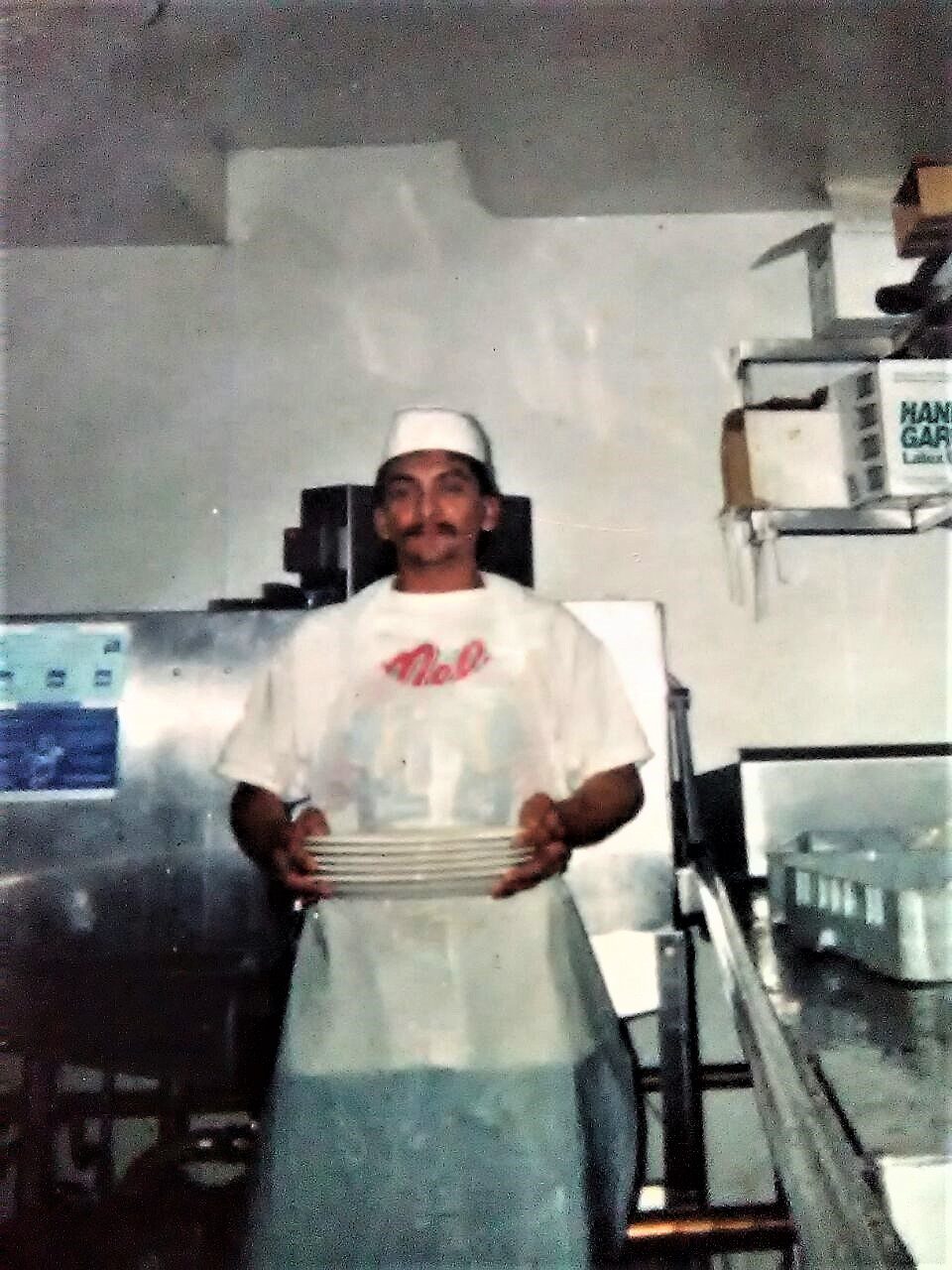

An indigenous Mayan man from the Yucatán who had come to the United States to support his family, Góngora worked in restaurants in San Francisco for years, faithfully sending remittances so that his family could build a house. After struggles with substance abuse and an eviction, he had fallen into homelessness. The entire family was shattered by his death: His brother, José, who also immigrated to the city and had lived with him before they lost their apartment; his cousin, who also lived in San Francisco; and his widow and children back in the Yucatán, who hadn’t seen him in years.

In the months before the June 2022 recall election, IIB attorney Rebecca Young had worked to get the investigation into Góngora’s death to the point where the IIB could impanel a grand jury to make a charging decision. Two workdays after Jenkins was sworn in as Boudin’s replacement, Young emailed the new top prosecutor requesting an appointment to discuss her cases, anxious to know how they might be impacted by the change of leadership. Three days after that, Jenkins fired her in a call that Young had mistakenly assumed was going to be a case meeting. Lateef Gray, the IIB’s managing attorney under Boudin, was fired the same day as Young, leaving only one attorney, James Conger, to manage all the IIB cases on his own for weeks. (Gray didn’t respond to several requests for an interview for this piece; Conger declined to comment.)

Young says she felt like she had failed the family. “I worked so hard just to have it go nowhere,” she told me, adding that she assumes the case won’t go forward since it was never filed.

The sudden changes to IIB staffing after the recall left the Moore and Góngora families reeling—the Góngoras, for instance, had an upcoming meeting to discuss their case with Young and Kate Chatfield, Boudin’s chief of staff, both of whom were now gone.

On July 21, Jenkins announced that Darby Williams, an attorney who prosecuted general felony cases at the office and who had previously worked at IIB under Gascón, would manage the bureau. Two days after Williams officially took over the IIB, Camarena wrote to her asking for updates on the case and wondering about accessing victims services, which the family had been in touch with during Boudin’s tenure. “This is a matter of urgency for us as it must be for you,” she concluded.

Soon after, Williams sent a brief reply telling Camarena that she needed time to familiarize herself with the case, stressing that she would reach back out when she was ready to discuss it further, and promising to have someone from victims services follow up. When Camarena replied with several more questions, writing, “What may we do to help you step into our shoes and understand the type of emotional and psychological grind it is for the family to fear that justice for Luis is once again at risk due to bureaucratic changes?” Williams never responded. Camarena and the Góngora family haven’t heard from Jenkins or Mark Koo, the IIB’s most recent attorney hire, either. And victims services never did get in touch.

“I asked her to give me a reassurance that she’s prioritizing the review of Luis’s case and taking steps to preserve the investigation work carried out by her predecessors and she did not respond at all,” Camarena told me. “All of that together let me know that she had no intention to seek justice.”

Camarena had also asked Williams if she’d consulted with Young about the case, writing, “I’m sure she can be extremely helpful in explaining the current progress.” But Young says Williams never contacted her to ask about her months of work on either police shooting.

The internal emails I obtained show that Williams herself was concerned about her lack of knowledge about the IIB cases. Discussing one case with Conger on Aug. 3, she wrote, “I am sure you can appreciate that I know little about any of these cases and the concern that brings when going to court.” But Williams emphatically declined when Conger, the sole holdover from the Boudin-era IIB, offered to contact Young, who had previously worked on the case. “That would not be appropriate,” she replied. “I will figure it out.”

“He was an angel to me”

Gascón’s IIB investigated but never charged Kenneth Cha, the officer who shot and seriously wounded Sean Moore in 2017. Moore’s mother, Cleo, says he was denied proper medical care at San Quentin State Prison, where he died three years later, in 2020. After the Marin County coroner ruled Moore’s death a homicide, Boudin decided to reinvestigate the case.

For Cleo, who is in her eighties, the agony of losing her son still feels as raw as the day it happened. Losing her husband of nearly six decades the same year as Sean only added to the grief. They had both worked in service of San Francisco for many years—she as a nurse at SF General, her husband as a city bus and trolley operator. She still struggles to understand how the same city they dedicated their lives to took away their son. “I did what I could for the citizens of San Francisco,” she told me, “and I’ll say to anybody, my son did not deserve to be killed the way he was.”

As a teenager, Sean loved basketball, and he was popular with girls. But a schizophrenia diagnosis upended his life. “I’m not trying to paint a picture of my son being an angel,” Cleo said, “but he was an angel to me.”

The pain of her son’s death has been compounded by the protracted nature of the court proceedings surrounding it. To both Cleo and Young, the IIB attorney who had been assigned to the case, Cha’s counsel seemed to be deliberately stalling in advance of Boudin’s recall election this past summer.

“I have been sitting in the courtroom since January of 2021, every month,” Cleo said. “What his attorney has done, he has come into court every month and he has decided that he doesn’t have what he needs … They kick it off to the next month … he just went on and on and every month it was the same exact thing. And then we knew what he was doing. He was prolonging this until [Jenkins] took office.”

Emails from the office indicate the Cha prosecution itself could now be up in the air under the new IIB. After Conger, who at the time was the only remaining attorney from Boudin’s IIB team, took over the case by default, he tried setting a court date for late September, where a judge and lawyers would determine a future date for a preliminary hearing. But Cha’s lawyer, Scott Burrell, quickly interjected to tell the judge that he and Williams, Conger’s supervisor and the new head of the department, had already agreed on a much later date for the hearing—after the special election. In his email, Burrell also informed the judge on the case that Williams had told him the DA’s office was now reconsidering the charges against Cha, writing, “We discussed the time necessary to complete a serious review and are asking that we set the matter for November 16.”

Like Cha’s prosecution, the case against Samayoa had been pushed back multiple times before the recall—and like Moore, the victim’s family accuses the officer’s defense team of stalling. After Williams took over the IIB, the office asked to postpone a preliminary hearing for Samayoa initially scheduled for Aug. 18, where evidence in the case would have been made public. The next court date is now scheduled for Dec. 1—again, not even a preliminary hearing, but a meeting to set a future date for it.

Randy Quezada, a SFDA spokesperson, told the San Francisco Chronicle that Jenkins needed more time to review the case and claimed Gascón had first declined to prosecute the officer before Boudin’s decision to pursue it, but former Gascón chief of staff Cristine Soto deBerry told the paper that Gascón never declined the case and it was still open when Boudin took office. (I asked Quezada for clarification, but did not receive a response.)

Emily Lee, co-director of San Francisco Rising, a local progressive organization, vocalized a fear born of these delays that she hears from families. “They’re very worried that post-election, very quietly, the DA might choose to drop charges,” she said.

Veronese, one of Jenkins’s opponents, has also criticized the new DA for “punting” the cases until after the election. “She doesn’t want to be held accountable for the choices she makes,” he told Mission Local.

After Jenkins was appointed as DA, O’Neil’s aunt April Green demanded a meeting with her. The encounter, at which Williams was also present, took place on August 24. Green called me afterward, perturbed by one thing in particular: Green said that Williams told her prosecuting law enforcement killings would require proof “beyond a reasonable doubt, and then some.”

“Why should this officer get a higher burden of proof than anyone else?” Green asked. “I looked at her and I knew then: you’re trying to find an out.”

“I’m just in limbo”

It’s unclear why Jenkins and Williams kept Conger around longer than the other IIB attorneys who were fired under the new regime; neither responded to questions for this story. But the emails I obtained show that they were done with him by the middle of August—and that they were just as eager to kick him out of the IIB as the other lawyers who staffed the department under Boudin.

On Aug. 17, just five days after Jenkins reassigned Conger away from the IIB and into the general felonies department via an all-staff memo, he emailed the facilities manager to say that he returned from a late meeting to find himself locked out of the IIB office. Williams, who was copied on the exchange, responded directly to the facilities manager, chastising Conger for being too sluggish in packing up and leaving the IIB.

“Mr. Conger has not been diligent in effectuating his physical move,” Williams wrote. “I appreciate that he is now locked out but I can attest to the fact that over the last two days he has been significantly slow in moving.” She also asked that the office immediately remove his access to IIB documents, writing cryptically, “I have concerns.” Only afterward did the office send Conger his new office seating assignment, “as of tomorrow.” Conger emailed that he would be in court first thing the next morning and could be there all day, but could circle back “and begin my move.”

The following morning, Williams followed up with another email to the facilities manager insisting that Conger vacate his IIB office that day, “even if he has to do so during lunch,” and that they restrict his access to the IIB offices for good. The next day, she emailed Conger expounding on the “noble requirement” of confidentiality and asking that he “avoid communication with members of the public, friends, family, former IIB co-workers, and the persons involved in the investigations (by family relationships or otherwise) about subject matter related to your time here in the IIB-Unit.” She copied a number of higher ups at the DA’s office on the email. Soon after his forced exit from the IIB, Conger decided to leave the DA’s office altogether.

With every attorney on Boudin’s IIB out, victims’ families feel completely out of the loop.

December 1, Samayoa’s next court date, is also the fifth anniversary of O’Neil’s killing. Green told me she’s going to keep fighting for her sister, O’Neil’s mother, who has dementia. “She’s not forgotten that her son was murdered by a police officer. She’s forgotten a whole lot, but not that,” Green said. “Before she closes her eyes, I want to make sure that she can close them in peace, knowing that justice has been served.”

Cleo Moore is also waiting for her next court date on November 16, as she has done for so many months. It particularly pained her to see a television interview with Jenkins where she spoke of meeting with victims’ families. “This Miss Jenkins has never, never never spoken to me in her life,” Moore said. “Nobody has even tried to contact me. Not a soul. I’m just in limbo.”

“I feel like I’m being shut out,” said Green. “Like I’m out in the dark.”

“Gross misuse and abuse of resources”

If Jenkins cleaning house wasn’t direct enough, Williams made it crystal clear that police prosecutions would be handled differently in a bombshell email that circulated inside the office three weeks after she became the IIB managing attorney.

In her letter, Williams excoriated former IIB staff, accusing them multiple times of “gross misuse and abuse of resources” and saying that “attorneys were employed in this Unit who were unqualified to work in it.” She criticized Boudin’s IIB for failing to close out cases in a timely fashion, noting that there were 36 open investigations going back to 2015. Gascón’s IIB appears to have filed many more declination reports than Boudin’s did relative to both men’s time in office; Boudin’s IIB also spent significant time taking another look at cases and bringing one to trial.

Williams also accused the former staff of investigating police officers, “not because the facts warranted those investigations” but because of “‘mission-like’ perspectives.” She wrote: the “lack of oversight and submission of the Unit’s members to the political whims of former leaders also deeply corrupted the Unit.” (You can read the full memo here.)

Young called Williams’s allegations “red herrings” to justify changes to the IIB post-election.

Lee, of San Francisco Rising, rejects the implications that pursuing police shooting cases is inherently political.

“If you don’t want to have the same thing thrown in your face, then you should actually treat these cases with what they’re due, and that means an actual impartial investigation of the facts,” she said. “I just think that’s all the victims are asking for—and if [Jenkins] disagrees for some reason, be transparent about it.”

Although Jenkins and Williams have both been tight-lipped in public about their intentions for the police killings that Boudin’s IIB tried to prosecute, Williams didn’t hold back in the internal email, calling the IIB’s reopening of cases investigated by the previous DA “baseless.”

“An injustice to all human beings”

On October 20, the families of Sean Moore, Luis Góngora Pat, and Keita O’Neil held a rally outside Jenkins’s office along with a number of community groups, including San Francisco Rising. April Green spoke, then Sean’s mother, Cleo Moore, resting on her walker near the podium. Cleo’s other son stood next to her, holding a photo of Sean at his high school graduation.

Next, José Góngora Pat spoke briefly in Spanish. “I came today to ask for justice from the district attorney,” he said. “What the police have done is an injustice to all human beings.”

I spoke with Camarena a few days later. “I know that for people outside the circles of these families and those of us who support the families, it might seem like these cases happened a long time ago,” she said. “But being in that rally, for me, it reminded me of how fresh the pain and the suffering is for these families.”

Before the rally, Camarena and José had spoken to another journalist. “At some point she says, ‘how do you feel,’ and he points to his heart and he just says he carries Luis in there,” Camarena said. “But what he’s told me in the past is that it’s just like a dagger in his heart.”