Everything You Always Wanted to Know About State Supreme Courts

Why these courts matter, how they work, and the levers for changing them: Bolts answers your questions on these powerful institutions.

Daniel Nichanian, Quinn Yeargain | August 22, 2023

State supreme courts have come under a brighter spotlight as battlefields for some of today’s most pressing issues, from abortion rights and climate to extreme sentencing and ballot access. And attention has intensified around the elections and appointments that decide who sits on them.

Most obviously, these courts have become an urgent route for liberal litigants in light of conservatives’ durable majority on the U.S. Supreme Court. State courts get to interpret state constitutions, which often protect rights and liberties more expansively than the U.S. Constitution, and they’ve proven friendly to arguments that wouldn’t succeed in federal court. The right has also focused on them to expand its control over the judiciary.

But these courts have even more clout than you may realize. They can shape virtually any policy area that state and local governments touch. They’re likely to have the final word on all cases filed in state courts, and many play additional roles that extend far beyond deciding cases, from crafting the rules of criminal trials to taking part in redistricting and certifying elections.

And yet these courts’ exact powers and procedures often remain well under the radar. What justices do and how they’re selected varies widely from state to state, and it always differs from the federal system. Most states elect justices but have their own twist on electoral rules, while some courts are shaped by commissions largely out of public view—and nearly all serve some idiosyncratic function with little scrutiny. These distinctions all influence how each court acts and what might be levers of change.

Today Bolts is publishing a new state-by-state resource that plunges into the weeds of these critical judicial powers. For each of 54 courts—accounting for the highest court in all 50 states, two of which have two separate high courts, plus Puerto Rico and D.C.—we cover every nook and cranny of how they are organized, what functions they serve, and rules for judicial selection.

But here we also wanted to take a step back. Why should we care about state supreme courts? What types of cases do they even hear? And what do we know about the balance of power between liberals and conservatives foothold on these courts across the country? Below is our FAQ to answer your big questions on state supreme courts.

I follow the U.S. Supreme Court: Why also care about state supreme courts?

If state and local governments have any involvement in an issue, you can bet that state supreme courts shape public policy on it. Why is abortion more widely available in this state than in neighboring ones? Why are police officers harder to prosecute in one jurisdiction over another? Why does this state better protect the rights of employees or access to mail-in ballots? The answer often has to do with how legal cases were resolved by state supreme courts, and who was sitting on them when they did.

In fact, many cases begin and end in state court, and never interact with federal judges. That includes countless civil lawsuits, and the vast majority of criminal prosecutions. These cases are heard within each state’s separate judicial system, and then work their way to the top state court that has supreme authority over their outcomes.

That’s how state supreme courts end up with the final word on critical cases—whether a lawsuit against South Carolina’s abortion restrictions, the appeal of a death sentence in Florida, or the legal battle over Illinois pensions. Some of these high courts also have idiosyncratic roles such as drafting bail schedules or approving pardons, and they can shape the rest of the judicial branch: That’s information that Bolts’ new state-by-state resource supplies.

Why would a case end up in state courts instead of federal court?

By-and-large, federal cases involve allegations that something or someone violated federal laws or the U.S. Constitution, or involve large financial amounts, inter-state disputes, or federal agencies.

Everything else is likely to end up in state court, and possibly escalate to a state supreme court.

These can be civil cases—you can bring a lawsuit in state court, especially if you’re invoking your state’s laws or your state’s constitution—or they can be criminal cases. Every state has its own criminal laws, and local prosecutors can charge people for breaking them in state courts; and if you’re convicted of a crime, you can appeal all the way to your state’s high court.

What’s the role of state constitutions?

The rights inscribed in the U.S. Constitution only set a floor. Each state has a constitution that may have different language or protect rights that the U.S. Constitution doesn’t, at least if a state supreme court interprets it that way. How receptive a given court will be to such arguments, of course, will depend on its membership.

For instance, the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual” punishments is mirrored in many state constitutions, with some even banning “cruel or unusual” punishments, a grammatical tweak that may justify more expansive protections. And in each state, the supreme court will effectively have the final word on what exactly those clauses forbid.

In light of federal courts’ sharp turn to the right, many progressive and civil rights groups have prioritized filing state lawsuits by crafting arguments that rely on their own state’s constitution. They may argue, for instance, that its language enjoins climate action or protects reproductive rights.

But can’t the U.S. Supreme Court step in regardless?

Yes, if you’re unhappy with how your state supreme court decided your case, you typically can appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. But that court hears very few cases. It’s also extraordinarily unlikely to consider a case that involves a state supreme court interpreting its own state’s constitution or statutes.

In practice, state supreme courts have the final word on what rights their state constitutions provide, and on nearly all cases and lawsuits that work their way through the state court systems.

So what do these state supreme courts do, day-to-day?

Their primary role is to review decisions made by lower courts. Every state has its own judicial pyramid, like the federal system: there are trial courts, typically appeals courts, and a supreme court at the top. (There are variations on this structure; most notably, Oklahoma and Texas have separate high courts for criminal and civil matters.)

State supreme court justices decide whether to take up a case for review.

But these courts also serve many other functions. Most are responsible for supervising the operations of their state’s entire judicial branch, putting them in charge of vast bureaucracies. They appoint people to key spots, and decide on rules that everyone else must follow, from attorneys to lower-court judges. In many states they also write the detailed procedures that govern any criminal case, including major matters like how bail or sentences are calculated.

Some courts have even more direct powers. In Arizona, justices witness election certification. In Nevada, they sit on the pardon board. In Tennessee, they appoint the attorney general.

Our state-by-state database highlights these unique powers for every high court, including the role each plays in crafting the rules of criminal procedures, and in various tasks relating to elections.

How do states decide who sits on their supreme courts?

Every state sets its own rules for how justices are selected and how they remain on the court, and no two states do it exactly the same—and none do it exactly like the U.S. Supreme Court.

One rare trait that unites nearly all states is that justices serve set terms. They are on their court for defined periods of time and then must seek a new term. Only in Rhode Island do they serve for life with no age restrictions, like they do on the U.S. Supreme Court.

This alone makes the membership of state courts far more fluid than the U.S. Supreme Court’s. To top it off, some states even impose a mandatory retirement age, often between 70 and 75.

Otherwise, state systems differ a great deal. Broadly speaking, they fall into two big buckets as to how justices make it on the court.

Some states elect their justices from the get-go. People not yet on the court can run for a seat, and incumbents who want new terms may face challengers. States like North Carolina and Wisconsin, for instance, consistently have heated judicial elections.

In other states like Indiana and Vermont, justices are always first appointed onto the court, typically by a governor. But these states vary on whether an appointed justice faces elections once they’re on the court. In many states, justices must face retention elections at the end of their term—up-or-down elections in which voters decide whether an incumbent can stay on the court.

States also vary on how much latitude governors have when they select a justice: Some governors are free to choose anyone without even worrying about legislative confirmation. Governors making high court appointments in other states, like Missouri, are much more constrained and must choose from a shortlist preselected by a nominating commission over which they may have little control. And in Virginia and South Carolina, supreme court appointments are made by lawmakers with little involvement from the governor.

In practice, though, the difference between elections and appointments can get very blurry.

Take Minnesota and Georgia, which have regular judicial elections but nearly all sitting justices first made it onto the court through an appointment. That’s because justices often resign before their term is over, letting governors select a replacement with little constraint. Once appointed, these incumbents rarely face any opposition when they run for a full term.

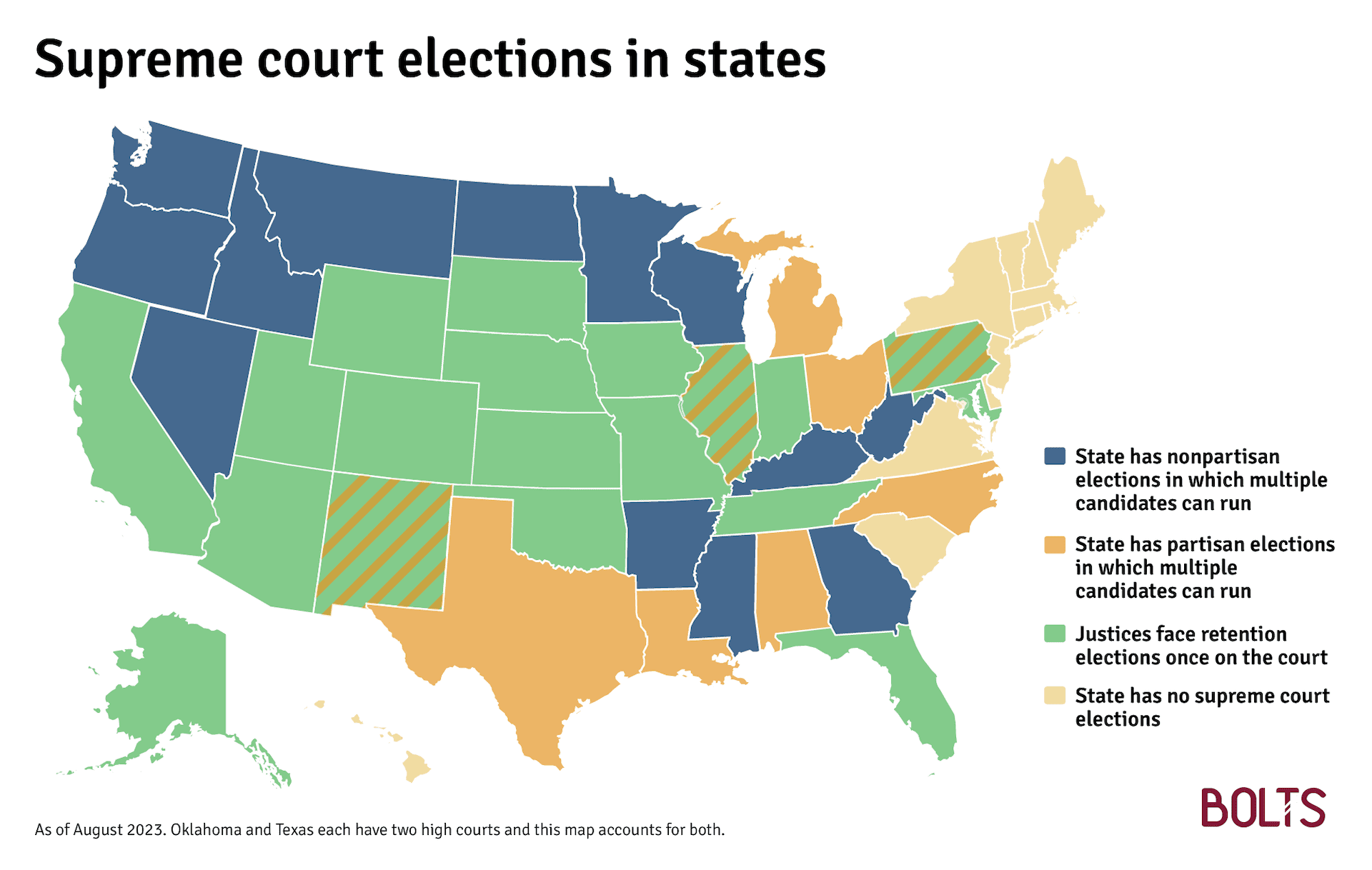

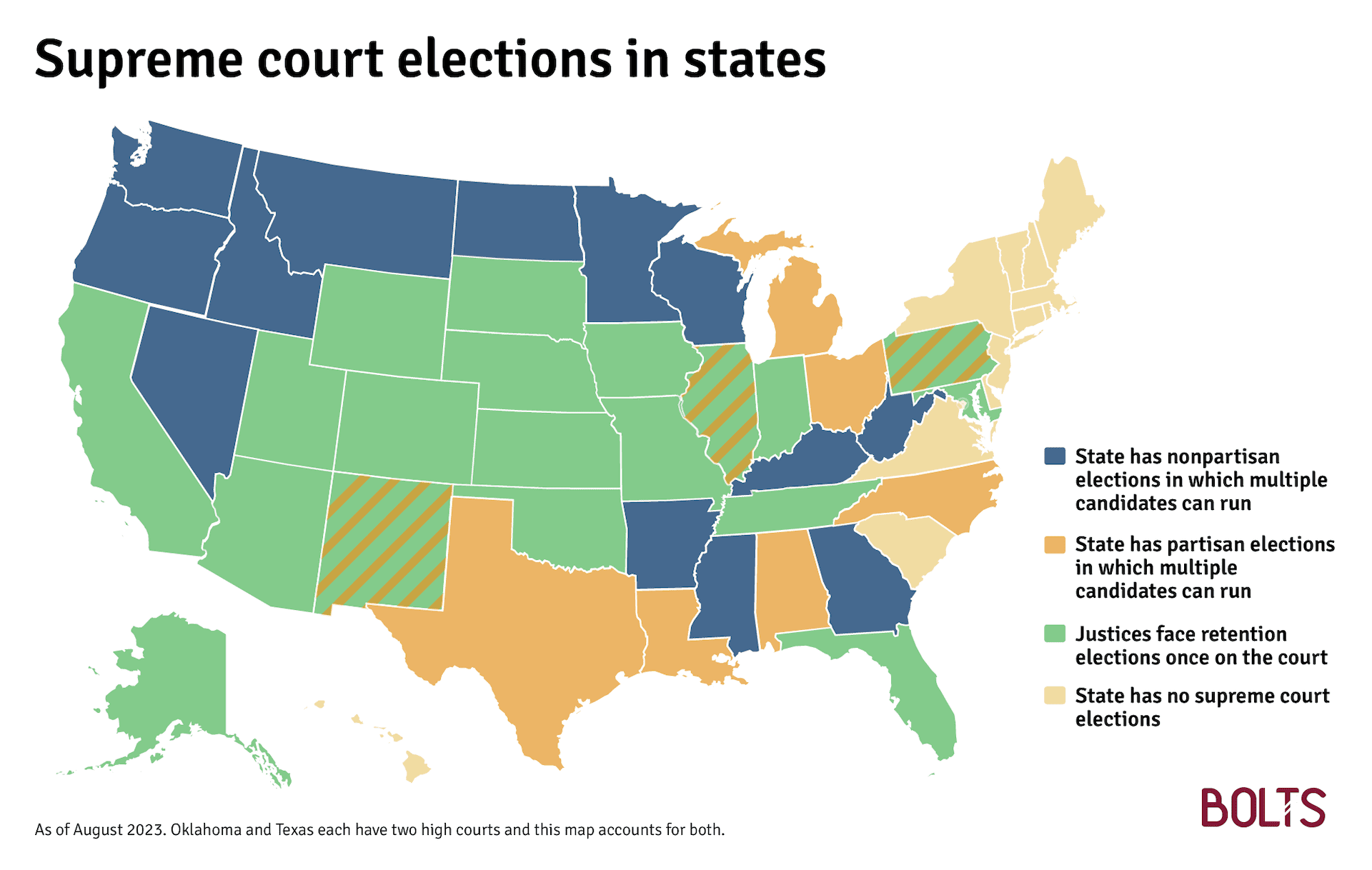

Does my state have elections?

Thirty-one states organize some sort of elections for supreme court justices.

In some states, justices only face voters once they’ve already been on the court for a few years, and only in the form of retention elections—no named challengers, just a yes-or-no vote on whether they should stay on the court.

Other states organize regular elections for all judicial seats: Every few years, any candidate who meets the qualifications to be a judge can run for a seat whether or not there’s an incumbent, and the winner joins the court. That sounds simple enough, but each state comes with some twist. Elections may be held at odd times, they may be canceled at the drop of a hat, and they may be governed by unusual rules that don’t apply to the state’s more prominent elections.

To complicate matters further, states may also mix up these models, using either regular or retention rules depending on the circumstances.

Are judges partisan or political officials?

Only nine states elect judges in partisan elections. Candidates there may file to run as a Democrat or Republican.

Still, in states that hold nonpartisan elections, parties and groups that support a political cause frequently get involved. Elections in Wisconsin are ostensibly nonpartisan, for instance, but are also very polarized. Other states with nonpartisan systems have sleepier elections.

Similarly, in states where justices are appointed, party affiliation is not a formal factor in the process, but the political leanings of prospective appointees are often a factor on the decisions of the governors or lawmakers who make the selection—much like in the federal system.

That may be true even in states that constrain a governor to a list preselected by a nominating commission made up of legal professionals—a process that is meant to be more meritocratic but does not eliminate political considerations. The shortlist may present various options that preserve a governor’s ability to shape the court’s direction, and some commissions also have an ideological bent. There’s often backdoor maneuvering about who sits on them, with governors or legislative leaders shaping their membership. Florida’s commission, for instance, has helped Governor Ron DeSantis move the state’s high court to the right, while New York’s has faced scrutiny for leaving jurists of color off of nominating lists. In Iowa, the GOP recently changed its commission to give the governor more control over who sits on the commission.

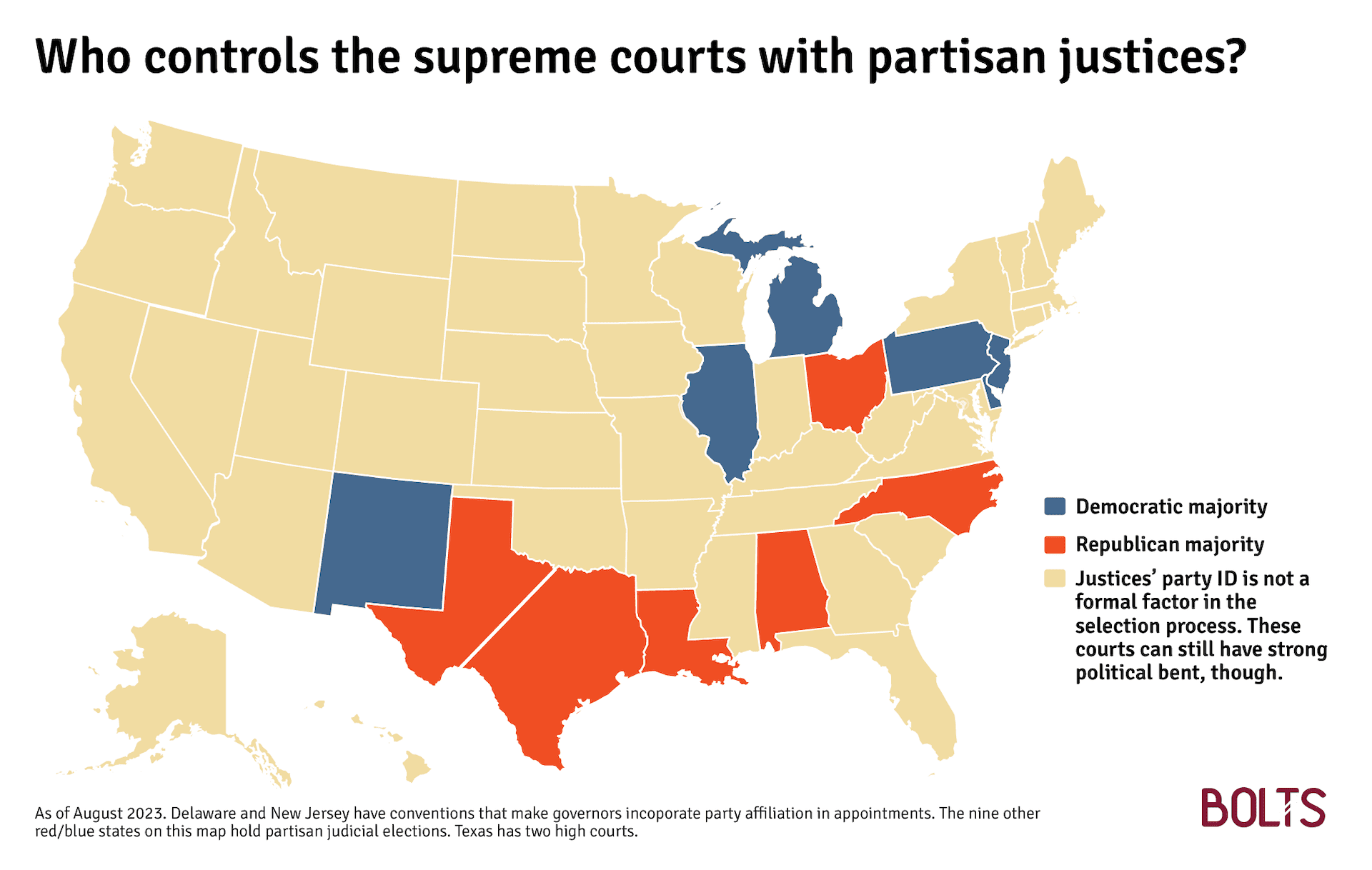

Can you tell me which party, or which ideological side, controls which court?

This is a difficult question. Only 12 high courts explicitly integrate justices’ party affiliation into their selection. That’s usually because the justices are elected in partisan elections, but it may also be because there’s a formal requirement (Delaware) or informal convention (New Jersey) that there be some partisan balance on the court.

In those states, it’s at least possible to say which party holds a majority of the court.

As of today, 6 of these courts have a Republican majority and 6 have a Democratic majority. (Two of those Republican majorities are in Texas, which is a rare state with two high courts.)

But judicial philosophies do not always map onto judges’ partisan affiliation.

Inversely, courts that are technically nonpartisan may have a strong ideological lean. They may have a coherent majority that constantly favors liberals or conservatives, or justices whose careers demonstrate a strong affiliation to a political cause. In Arkansas, for instance, a majority of supreme court justices now have ties with the Republican Party after Governor Huckabee Sanders appointed the chair of the state GOP to the court this summer. Wisconsin’s court flipped from a conservative majority to a liberal one as a consequence of the 2023 elections. New York’s conservative-leaning court took a step to the left this spring after a heated battle in which progressive groups fought the governor’s initial nomination.

Assessing a court’s politics may then entail identifying other proxies for judicial ideology. In states with judicial appointments, we can start by assessing the party of the governors who selected the justices. In Minnesota, for instance, all justices as of now have been appointed by a Democrat, while in Arizona they’ve all been appointed by a Republican.

This is a reliable predictor in some states—but it can be an imperfect proxy in others since some governors must get their choices approved by the legislature, or are constrained to choosing from a commission’s shortlist. Then again, governors can try to craft these commissions to their liking to gain more influence over the process, frequently far out of view of the general public.

The devil is in the details, which is why Bolts’ state-by-state database lays out more information on each court’s process.

How do state supreme courts affect a specific issue I care about?

On any issue, lawsuits may put a state’s statutes and practices under court scrutiny, at which point it comes down to what’s written in the state’s constitution and laws—and who has the power to interpret them. Many courts also have rulemaking powers that give them the ability to upend some matters even more directly. Here are some examples of what to watch on just six key issues.

If you care about abortion rights: The U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, but state supreme courts can interpret their own constitution as recognizing a right to abortion. A Bolts analysis found that a dozen had done so by the time of the Dobbs ruling, and more since. But conservative gains can undo these rulings. In 2018, Iowa’s supreme court ruled that the Iowa constitution guarantees a right to abortion but then reversed itself in 2022 after the arrival of new conservative justices.

If you care about criminal justice: State courts shape the rights of people accused of crimes at every stage of a criminal case, and some courts have pushed back more than others against invasive police practices or extreme sentences. Many supreme courts also write their state’s rules of criminal procedure—lengthy codes that govern how cases unfold, from the issuance of warrants to the calculation of sentences. Some courts even set bail schedules. This is an often-overlooked but potent policymaking role. In 2021, for instance, Arizona’s supreme court eliminated peremptory strikes, the practice by which attorneys can eliminate someone from the jury pool without stating a cause. Explore our state-by-state guide to learn the extent of each court’s rulemaking role with regards to criminal procedure; the guide also specifies for each court whether a court is involved in drafting sentencing guidelines and setting bail schedules.

If you care about LGBT rights: Some state constitutions provide greater protections for individual rights than the U.S. Constitution, and LGBT activists have turned to state courts when federal courts have been unwilling to affirm certain rights. In 2003, Massachusetts’ supreme court recognized marriage equality, setting off a wave of supreme courts that did the same before the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nationally. And as states are now passing new anti-trans legislation, state advocates are again turning to state courts.

If you care about education: Many state constitutions contain provisions that state courts have interpreted as creating a right to education, and activists have argued in court since the 1970s that unequally or inadequately funding schools is unconstitutional.

If you care about the environment: As the climate crisis rages on, the regulatory power of environmental agencies often hinges on decisions by state supreme courts. Plaintiffs have also invoked environmental rights to push for climate action, with some success; Hawaii’s supreme courts, for instance, recently affirmed a robust interpretation of such rights in its state constitution, and a case in Montana that involves a right to a “healthful environment” could soon make its way to that state’s supreme court.

If you care about how elections are run: The shape of democracy can hinge on the composition of state supreme courts, which play a crucial role in blessing or rejecting voter suppression. Lawsuits are constantly filed in state courts challenging election law and practices, anything from voting procedures and gerrymandered maps to legislation restricting access to mail ballots. A change in the court’s membership can lead to major changes in election law, as in North Carolina this year. And some supreme courts are tasked with more direct roles in the running of elections, like supervising the drawing of new maps or participating in the certification of election results.

For more information, explore our state-by-state guide to how each state’s high court.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that covers the nuts and bolts of political power. But it takes resources to plunge into the weeds and produce work like this. If you appreciate our value and want to support us, you can become a member or make a contribution.