California’s Midterms Bring Plenty of Forks in the Road for Criminal Justice Reforms

Across dozens of sheriff and DA elections, reformers target incumbents over “tough-on-crime” policies or dire jail conditions, but they are also playing defense in offices they hold.

Daniel Nichanian | March 29, 2022

Orange County’s scandal-plagued sheriff’s department is known for evidence that goes missing, the shady use of jailhouse informants, and shielding deputies from discipline. But Sheriff Don Barnes won’t need to break a sweat or answer questions about his record to secure another term this year. No one filed to challenge him in the 2022 elections.

Nextdoor, the Los Angeles County sheriff’s department has a similar history and faces an impeding investigation into a secret unit accused of targeting his political enemies. Sheriff Alex Villanueva, whose deputies have been accused of harassment and organized violence against the community, faces an avalanche of challengers—eight in total—in what is arguably the nation’s most important law enforcement election this year.

The filing deadline for candidates passed earlier this month in California, filtering out dozens of counties where voters won’t get to weigh in on criminal justice policy this year. As happens nearly everywhere in the country, district attorneys and sheriffs like Barnes across the state are now certain to stay in office until 2026 because no one else is running.

Still, millions of voters will see competitive elections for these powerful offices, which enjoy vast discretion on the rules and conditions of the local criminal legal systems. At stake are issues like whether the state continues to send people to death row—with a competitive DA race in Riverside County, one of the most aggressive jurisdictions in the entire country when it comes to seeking the death penalty—or whether minors should be prosecuted as though they are adults, a major fault line in Santa Clara County’s heated DA election.

California offers no centralized database of county-level candidates after the filing deadline, so Bolts created a cheatsheet to paint a clearer picture of what will unfold in coming months. Candidates will appear on the state’s June 7 ballot without party affiliation listed; if no one receives more than 50 percent of the vote, a runoff will be held in November between the top two candidates.

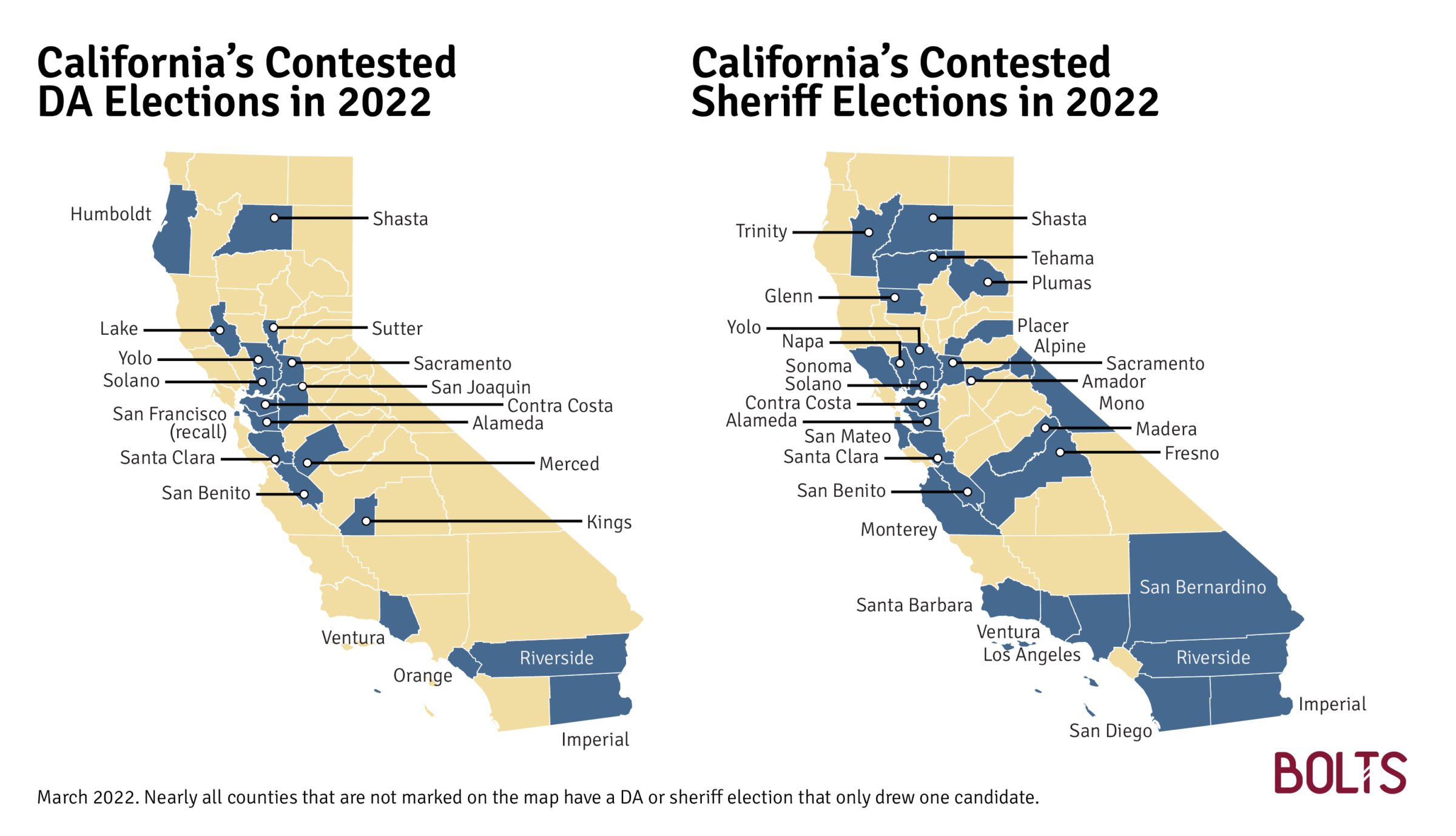

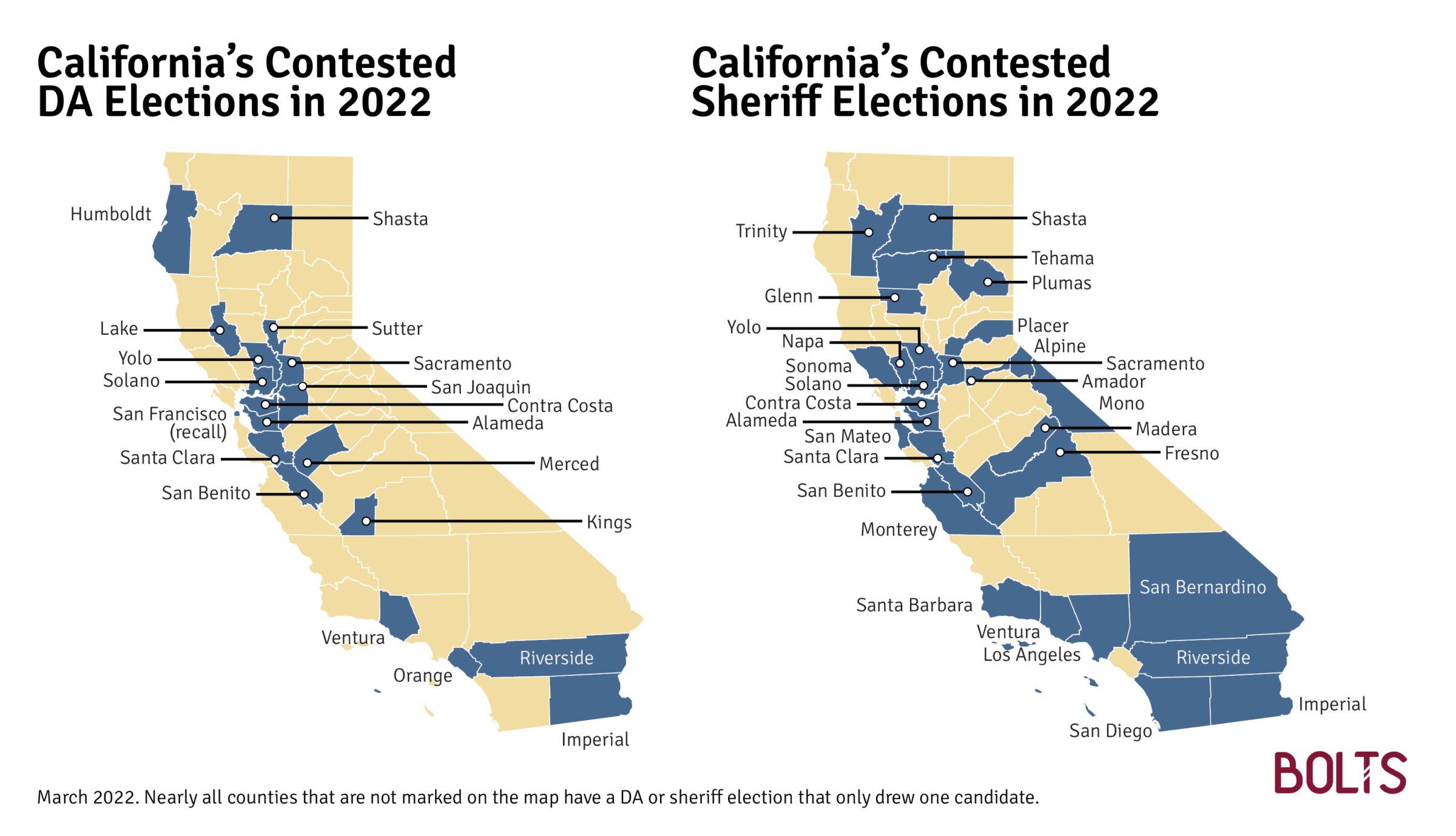

Out of 57 counties with sheriffs’ offices on the ballot, 30 drew multiple candidates. On the prosecutor front, San Francisco will hold a recall election against DA Chesa Boudin, organized by opponents of his reforms in office. Of the 56 other counties with regular DA races, 18 counties drew multiple candidates this year—seven of which are bigger than San Francisco, including Orange County, where DA Todd Spitzer faces a new fallout from racist comments.

In fact Orange County is the most populous in the entire nation to hold a contested DA election this year. All in all, more than 16 million Californians live in counties with contested DA races, and more than 30 million in counties with contested sheriff elections. Of course, plenty of other elections matter greatly to criminal justice and law enforcement this year, notably the statewide attorney general election that has become a major proxy battle over criminal justice reform, and plenty of local elections for mayor, city attorney, and council.

See: The full list of candidates running for sheriff and DA in California.

These elections occur against the backdrop of heated debates about the future for criminal justice reform in California. The state has taken major steps away from the “tough-on-crime” consensus that sent its prisons and jails ballooning over the past decades, often through changes that voters have directly approved. In 2014, for instance, voters adopted Prop 47, which lowered the severity of some property crimes, and they rejected rollback efforts in 2020. In recent years, progressive candidates Boudin and George Gascón also won competitive DA races in San Francisco and Los Angeles on promises to lower incarceration. Both DAs went on to champion major changes to their offices like restrictions on sentencing enhancements and cash bail, efforts to reduce long prison sentences, and a ban on seeking the death penalty.

Boudin and Gascón have since become lightning rods for critics of decarceration, who connect their policies to the rise in homicides and to broader concerns about public safety—including fears over highly-publicized burglaries, which have become a dominant issue in San Francisco. Boudin’s recall is among the highest-profile tests of the electoral resonance of this argument in the 2022 midterms, as he is arguably the most emblematic member of the nation’s “progressive progrecutor” movement alongside Philadelphia DA Larry Krasner, who easily won re-election last year after facing similar attacks. (Gascón is not on the ballot this year. One recall drive against him has already failed, though his opponents are now trying again.)

But reform proponents are pointing out that similar concerns over public safety are playing out in counties run by vocal foes of criminal justice reform. Orange County’s Spitzer paints neighboring Los Angeles in apocalyptic terms to bolster his own standing, a familiar strategy for public officials in more suburban areas that border major cities. But Spitzer’s more progressive opponent is pointing out that murders and other crimes have also risen during the DA’s tenure.

The same dynamic holds in Riverside County, another jurisdiction on Los Angeles’s doorstep that has sentenced more people to death over the past five years than any other in the nation.

Elsewhere, candidates are running to push criminal justice reforms much further in their counties. In Santa Clara County, public defender Sajid Khan accuses incumbent DA Jeffrey Rosen of being too punitive, promising a major overhaul if he is elected. Khan and Rosen have a long personal history, including Rosen threatening Khan with an ethics complaint during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, as Bolts reported in February.

Orange, Riverside, and Santa Clara are California’s three most populous counties with contested DA elections this year. Six other counties with at least half-a-million-residents also host contested DA elections this year. San Francisco’s recall election has dominated national attention. In Alameda (Oakland) and Sacramento counties, incumbents who have been critical of reform are not seeking re-election (Sacramento’s DA is running for attorney general); the field to replace them offers markedly different choices, with both reform-minded candidates and others more in line with the incumbents’ politics. In Contra Costa County, reform-minded DA Diana Becton, who in 2020 joined a progressive association with Boudin and Gascón, faces one challenger. A similar dynamic is playing out in San Joaquin County. And in Ventura County, an incumbent faces a deputy DA running on his experience as a prosecutor.

Missing from the list are plenty of populous counties like San Diego, where DA Summer Stephan will face no opponent; during her last term, Stephan tried to blunt the impact of hypothetical future reforms by pushing plea deals that required defendants to waive any rights they may have to to seek re-sentencing if the legislature passes new laws. Also missing from the list of contested elections is Kern County, where the DA has sought to go further than most in deploying carceral tactics against Calfornians experiencing homelessness.

Elections for sheriff are unfolding in a similar statewide context, since sheriffs have long been prominent foes of the state’s criminal justice reforms. By and large, there is little indication that this will change after 2022. In fact, one of the more influential Democratic critics of reform is trying to switch from the legislature to the sheriff’s office: Jim Cooper, an assemblymember who is also a former sheriff’s deputy, is one of the two candidates running for sheriff in Sacramento.

But these elections may also offer rare windows into the often disastrous conditions in the local jails that sheriffs supervise. San Diego’s jail has long been the subject of investigations into a string of deaths and other major concerns, and the county has responded by targeting a chief local journalist who was holding them to account. Sheriff Bill Gore is retiring this year, and a crowded field of seven candidates is running to replace him and inherit this system.

In Alameda County, JoAnn Walker is running on an unusual progressive ticket against Sheriff Gregory Ahern, who has also faced scrutiny for the high number of jail deaths under his watch. Walker has tied Ahern’s use of solitary confinement to a series of suicides at the jail. “How can they come out and be normal?” she asked about people held in the local lockup at a recent forum.

California has restrictive rules on who can run for sheriff, which boxes out anyone who is an outsider to law enforcement. Some reformers have sought to eliminate this barrier to more candidates, but in the meantime there remain limits on who can even try to change these offices. In 2018, Villanueva was a veteran of the Los Angeles sheriff’s department when he ran on promises to clean it up from the inside. Instead, one of his earliest decisions once he became sheriff was to rehire deputies who were fired for misconduct.

Catch up with our other primers on prosecutor and sheriff elections in 2022 on Arkansas, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Utah, as well as our national primer.