The DA Elections That Will Shape Prosecution in Texas This Year

Reform-minded incumbents defend their turf in two of Texas’ largest cities while challengers elsewhere seek to remake criminal justice policy.

Michael Barajas, Daniel Nichanian | February 23, 2022

Austin police bolstered their reputation for violence during the demonstrations that followed George Floyd’s murder, shooting so-called less lethal weapons like “bean bag” rounds into crowds of unarmed protesters, resulting in numerous severe injuries. The brutal response put Travis County District Attorney Margaret Moore in the hot seat, facing accusations that she hadn’t done enough to hold police accountable just as she fought to keep her job in the 2020 Democratic primary. Jose Garza, a former public defender and labor rights organizer who vowed to push for police reform, beat Moore by more than 30 points in that primary and was sworn in last year.

Last week, Garza’s office announced indictments against 19 Austin cops accused of assault and deadly conduct during the 2020 protests, including an officer who’s currently running for a Texas House seat. The indictments have rocked the local police department, and come on the heels of other charges Garza filed against law enforcement officers in his first year on the job.

The raft of indictments were also a reminder for Texas voters of the potential for DA elections to quickly change the landscape on policing and other criminal justice policies, just as early voting started for the state’s March 1 primary. Fifty districts are electing their next prosecutor across the state this year.

How these DA elections affect the criminal legal system in Texas will largely come down to races in four populous counties—Bexar (San Antonio), Dallas, Hays, and Tarrant (Fort Worth). In Bexar and Dallas counties, a pair of Democratic incumbents are seeking a second term after drawing conserative ire for reforms they’ve rolled out since winning in 2018.

In Hays, a Republican incumbent is retiring after overseeing an explosion in the local jail’s population. In Tarrant County, the GOP’s last urban stronghold that has been drifting blue, a right-wing lawmaker notorious for pushing book bans looks to replace a retiring Republican DA whose selective enforcement of election laws led to lengthy prison sentences for Rosa Ortega and Crystal Mason—women who mistakenly thought they could vote, and whose convictions have been cheered by the Texas GOP in the party’s crusade against voter fraud.

The results of these elections —in the March 1 primaries, May 24 primary runoffs, and November 8 general elections—could have profound consequences on local policies such as bail, the severity of sentences, the death penalty, and prosecutions that target reproductive and voting rights.

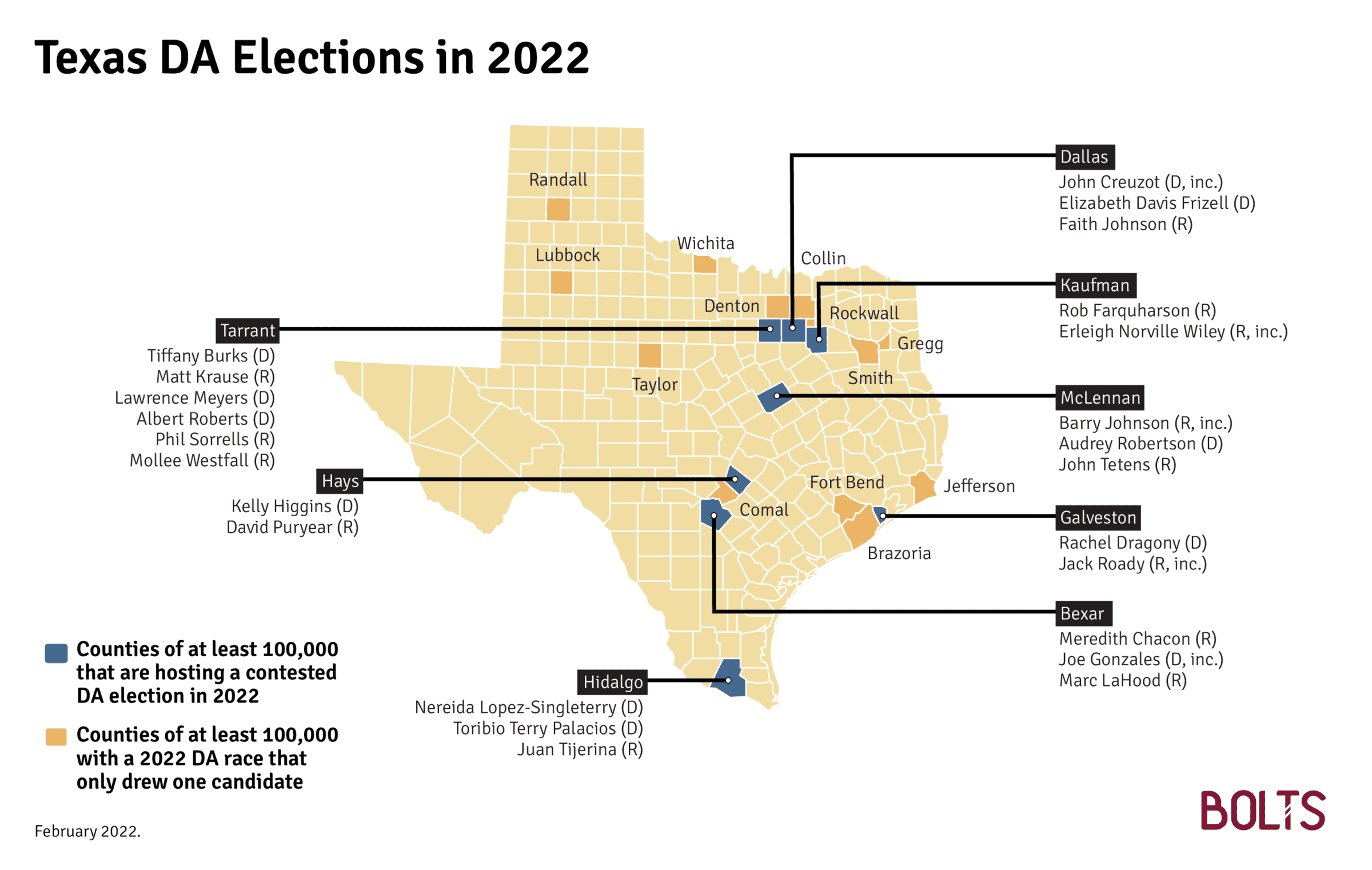

Despite this critical role, more than three-quarters of the state’s 50 DA elections this year only drew one candidate by December’s major-party filing deadline—most of them incumbents. (See the full list of elections and candidates.) That trend holds in the state’s most populous counties with DA elections. Besides Bexar, Dallas, Hays, and Tarrant, only four other counties with at least 100,000 residents drew more than one candidate, and reform stakes are not at the forefront, at least not yet. The vast majority of smaller Texas counties with DA races are also uncontested. (Most Texas DAs are on the ballot in 2024 rather than 2022.)

There is plenty more to watch in Texas besides DAs this year. While the state will only have a handful of sheriff’s races, other local offices with great influence on the criminal legal system are on the ballot. A prosecutor is deploying a tough-on-crime message to unseat a Republican incumbent on the state’s Court of Criminal Appeals, for instance. And Austin has several referendums in May, including one to decriminalize marijuana possession.

To kick off our midterm coverage in Texas, below is a guide to the year’s DA elections.

1. A dual rematch in Dallas

Dallas County’s DA election is a replay of 2018 in more than one sense. The same three candidates who ran four years ago have filed again. In the Democratic primary, former felony court judge Elizabeth Frizell will again face John Creuzot, the sitting DA who beat Frizell by a mere 589 votes in the 2018 primary. Just like four years ago, the winner will then face Republican Faith Johnson, who was the incumbent at the time. Johnson, who had gained national attention for actually trying killer cops for murder, then lost to Creuzot in the general election by a wide margin of 20 percentage points.

But the script has also partly flipped this time. In 2018, local reform advocates largely backed Frizell in the Democratic primary, but Creuzot deployed reforms after winning. He started refusing to prosecute certain drug cases and changed how it handles low-level theft, criminal trespass and other charges often associated with poverty. These changes triggered major attacks against Creuzot, from a police union calling for his removal to Republican Governor Greg Abbott accusing him of stoking crime. Ahead of next week’s primary, Frizell has echoed some of those same right-wing talking points, calling Creuzot’s reforms “dangerous.” Johnson, meanwhile, has overseen one of the nation’s largest and most-scandal plagued prisons systems since Abbott appointed her to the Texas Board of Criminal Justice after her 2018 loss.

2. A family rematch in San Antonio

Bexar County DA Joe Gonzales made jail diversion and other criminal justice reforms the focus of his winning campaign in 2018. But he said it was a personal threat from the county’s former DA that first inspired him to run. As a defense attorney before becoming San Antonio’s top prosecutor, Gonzales claimed that then-DA Nico LaHood threatened to destroy his law practice after Gonzales confronted him about withholding evidence in a case. Gonzales unseated LaHood in the Democratic primary and then won the general election that year, while LaHood eventually faced probation and a fine by the state bar.

Nico LaHood’s younger brother, Marc LaHood, is now running to unseat Gonzales. He is one of two Republican candidates vying to face the incumbent DA in the general election (Gonzales is unopposed in the Democratic primary). In a statement to the San Antonio Express-News, Marc LaHood delivered standard tough-on-crime attacks, like accusing the incumbent of “severing ties with law enforcement agencies.” LaHood must first face former prosecutor and local defense lawyer Meredith Chacon in next week’s GOP primary, and Chacon has also played up her proximity to law enforcement, saying she would stop treating police “as the enemy.” Gonzales has drawn predictable hostility from the local police union since taking office and expanding diversion programs meant to prevent arrest and convictions for people accused of minor offenses, like misdemeanor marijuana possession.

3. A race to the right in Tarrant County

Local DAs who espouse baseless claims of widespread voter fraud have become key foot soldiers in the Texas GOP’s efforts to police the vote. And Tarrant County DA Sharen Wilson, a Republican who announced her retirement this year, has been a prime example of how prosecutorial discretion can turn mistakes into “voter fraud” convictions that GOP lawmakers wield to justify stricter laws.

The GOP primary for Tarrant County DA could push the office even further to the right. Donald Trump has waded into the race to endorse Phil Sorrells, a judge and former prosecutor who vows to targeted undocumented immigrants as one of his main campaign issues.

He faces state Rep. Matt Krause, a member of the chamber’s “Freedom Caucus,” which has successfully pushed for arch-conservative legislation like the state’s near total ban on abortions. Krause helped spark the book-banning hysteria that has gripped school districts across the state. And he backed legislation, passed by Republicans in 2021, that created new voting restrictions and criminal penalties around voting and election administration—a notable record for a prospective DA in the county where Ortega and Mason were prosecuted. Mollee Westfall, a current felony court judge, is also running in the GOP primary for DA.

The winner will face one of three Democrats competing in next week’s primary. Tiffany Burks, a former deputy prosecutor under Wilson until last year, faces Albert Roberts, a former prosecutor in a neighboring county who came within 7 percentage points of unseating Wilson in the 2018 election. Former judge Larry Meyers has not run an active campaign, according to the Fort Worth Report. Tarrant County has trended blue in recent cycles, but Republicans continue to dominate local politics.

4. Hays County candidate takes pride in never having been a prosecutor

The two candidates in the open election in Hays County, home to one of the state’s public universities and the fastest-growing county in the nation, could not have introduced themselves to voters more differently.

David Puryear, the only Republican, puts his work as a staff prosecutor in various offices front and center. Kelly Higgins, the only Democrat, is a defense attorney who does the opposite. “I submit that not having been a prosecutor is, in this county at this time, a blessing,” Higgins writes on his website. “I’ve always been the guy who insists on the protection of the Constitution.”

Higgins vows to bring a “sea change” and “progressive vision” to the DA’s office and faults the retiring DA, Republican Wes Mau, for leaving cases to drag pretrial. The number of people detained pretrial in Hays has more than doubled since Mau became DA in 2015, according to data supplied by the county.

Higgins told Bolts that, to reduce the volume of criminal cases and trials, he would seek to grow the availability of diversion programs and review the legal basis for arrests and charges more rigorously; this is to stop what he describes as the cynical prosecution of cases “based on the calculation that there is enough evidence to proceed.” Higgins also said he would consult reformers elsewhere in Texas, noting that “Travis and Bexar Counties have elected progressive DAs.”

Higgins and Puryear, who did not reply to a request for comment on his own platform, will face each other in November.

5. Heated primaries in McLennan, Hidalgo counties

Only four other Texas counties with a population of at least 100,000 have contested DA races, and at this point in the campaign none of them are defined by major contrasts on criminal justice policy. It is still very early in Galveston County, which won’t see a contested race until the general election.

But in Kaufman, Hidalgo, and McLennan counties, primaries will likely decide the next DA. That may explain the acrimony unfolding in some of those races.

McLennan County DA Barry Johnson faces challenger John Tetens in the Republican primary, with both ratcheting up fearmongering rhetoric about crime. Tetens has support from local police associations and promises to pursue harsher punishments. Johnson has responded to the criticism in unusually strong terms.

“There is always an element of law enforcement that wants a rubber stamp in the DA’s office, and I am not going to do that,” Johnson told the Waco Tribune-Herald. But he has also turned to one of the uglier staples of “tough-on-crime” campaigning: attacking Tetens over his work as a criminal defense attorney, which Johnson says has contributed to putting “criminals back on the streets of McLennan County, where they can continue to prey on you and your family.” The GOP nominee will face Democrat Audrey Robertson in this conservative-leaning county.

Another DA candidate is attacking an opponent’s defense work in Hidalgo County, where Democratic DA Ricardo Rodriguez is retiring. One of the Democrats looking to replace him, Nereida Lopez-Singleterry, has blamed rival Toribio Terry Palacios for securing plea deals for his clients as a defense attorney. Palacios has also questioned his opponent’s ethics. Neither replied to Bolts’s questions about their policy platforms or their dispute. The winner of this Democratic primary will then face Republican Juan Tijerina; Hidalgo is a blue county, but Republicans are hoping to make gains in South Texas this year.

In Kaufman County, finally, the only challenger to Republican incumbent Erleigh Norville Wiley is Republican Rob Farquharson, who is emphasizing a traditionally tough-on-crime platform.

6. Most still run unopposed

In much of the state, there will be DA elections on the ballot but no contested races. Of the 50 districts with DA elections this year, 38 of them drew only one candidate, according to a Bolts analysis.That means 76 percent of the state’s DA elections are uncontested in 2022, the exact same rate as in 2020, when there were many more prosecutorial elections.

In 13 counties with at least 100,000 residents, only one candidate filed to run. Incumbents are completely unopposed in Brazoria, Comal, Collin, Denton, Fort Bend, Lubbock, Randall, Rockwall, Smith, Taylor, and Wichita. In Gregg and Jefferson counties, candidates who aren’t even incumbents effectively won just by filing to run, though John Moore and Keith Giblin have each worked for their respective DA offices in the past. (All of these unopposed candidates are Republicans other than in Fort Bend.)

These counties have a combined population of 4 million. Some are undergoing massive upheavals—Denton, for instance, swung toward Democrats by a net 24 percentage points between the presidential elections of 2012 and 2020. Public scandals around the criminal legal systems have swirled in other counties with uncontested DAs. But voters in these places won’t get a chance to weigh in on an office that largely drives criminal justice policy for another four years.