Public Defenders Shake Up Key Prosecutor Races from Arkansas to Oregon

A guide to the 2022 prosecutor elections in North Carolina, Oregon, Utah, Arkansas, and Nebraska.

Daniel Nichanian | March 11, 2022

This article is part of our ongoing series of primers covering DA elections in 2022.

The filing period for candidates to run for prosecutor closed in five states over the past month, adding clarity to the question of where the midterms may shake up the criminal legal system’s status quo. With primaries looming as early as May, criminal justice reformers are pressing their case from North Carolina’s biggest cities to Omaha and the Portland suburbs.

Public defenders and legal aid advocates are running in Arkansas, Nebraska, and Oregon, enlivening proceedings in places like Little Rock and Salem that have not seen a contested election in decades. In North Carolina, where racial justice protests drew thousands into the streets in 2020, challengers are now running on reform promises. And Utah brings the uncommon sight of a Republican reform incumbent who faces a tough-on-crime challenger.

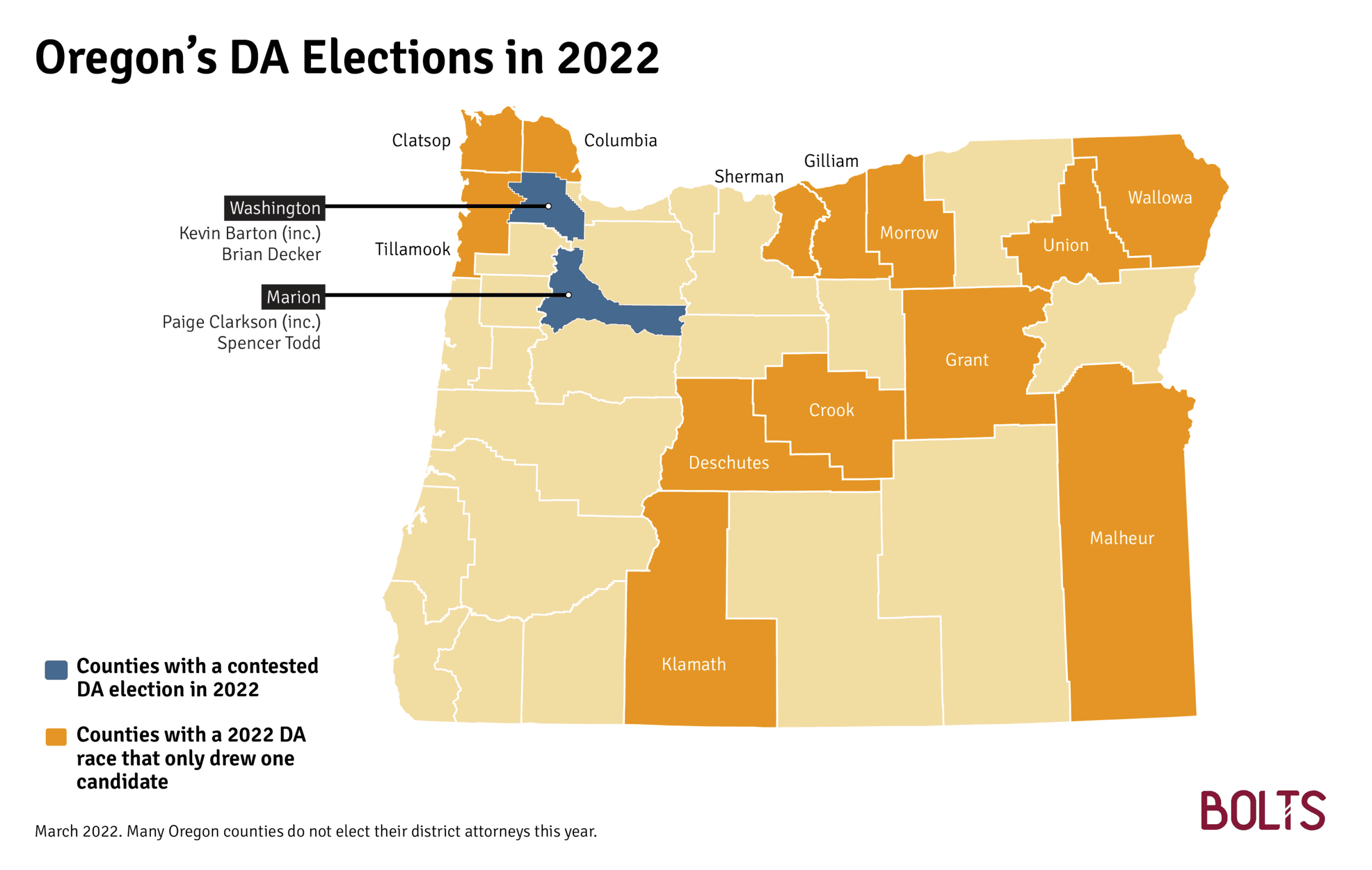

But away from those fireworks, the filing deadline is more often than not the end of the road for a prosecutor election, as most races only drew one candidate. In Oregon, whose filing deadline passed on Tuesday, just two of 15 DA elections feature multiple contenders.

The situation is only slightly less desolate in Arkansas and North Carolina, where filing deadlines passed last week. Roughly one-third of their elections will be competitive this year. In each of Nebraska and Utah, the two most populous counties at least will have contested elections. (In Texas, as Bolts reviewed last month, 76 percent of elections are uncontested this year.)

Still, those elections that will be contested offer rare opportunities to confront local injustices. Arkansas, for instance, has a unique law that criminalizes falling behind on rent, empowering local prosecutors who choose to use it. And North Carolina allows children to be prosecuted at an unusually young age, though the state reformed its statutes last year.

Below is Bolts’s preliminary guide to the prosecutor elections in those five states.

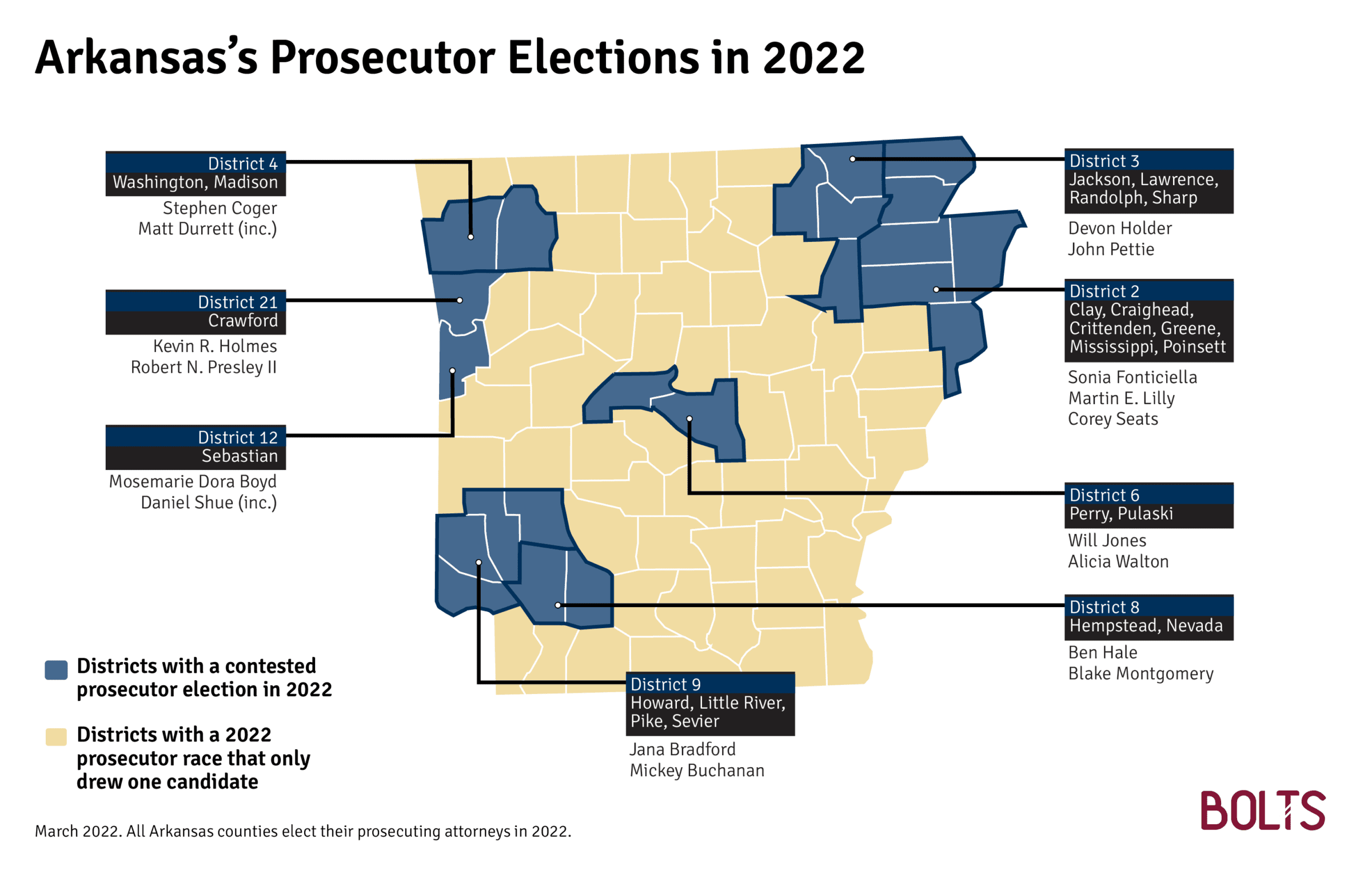

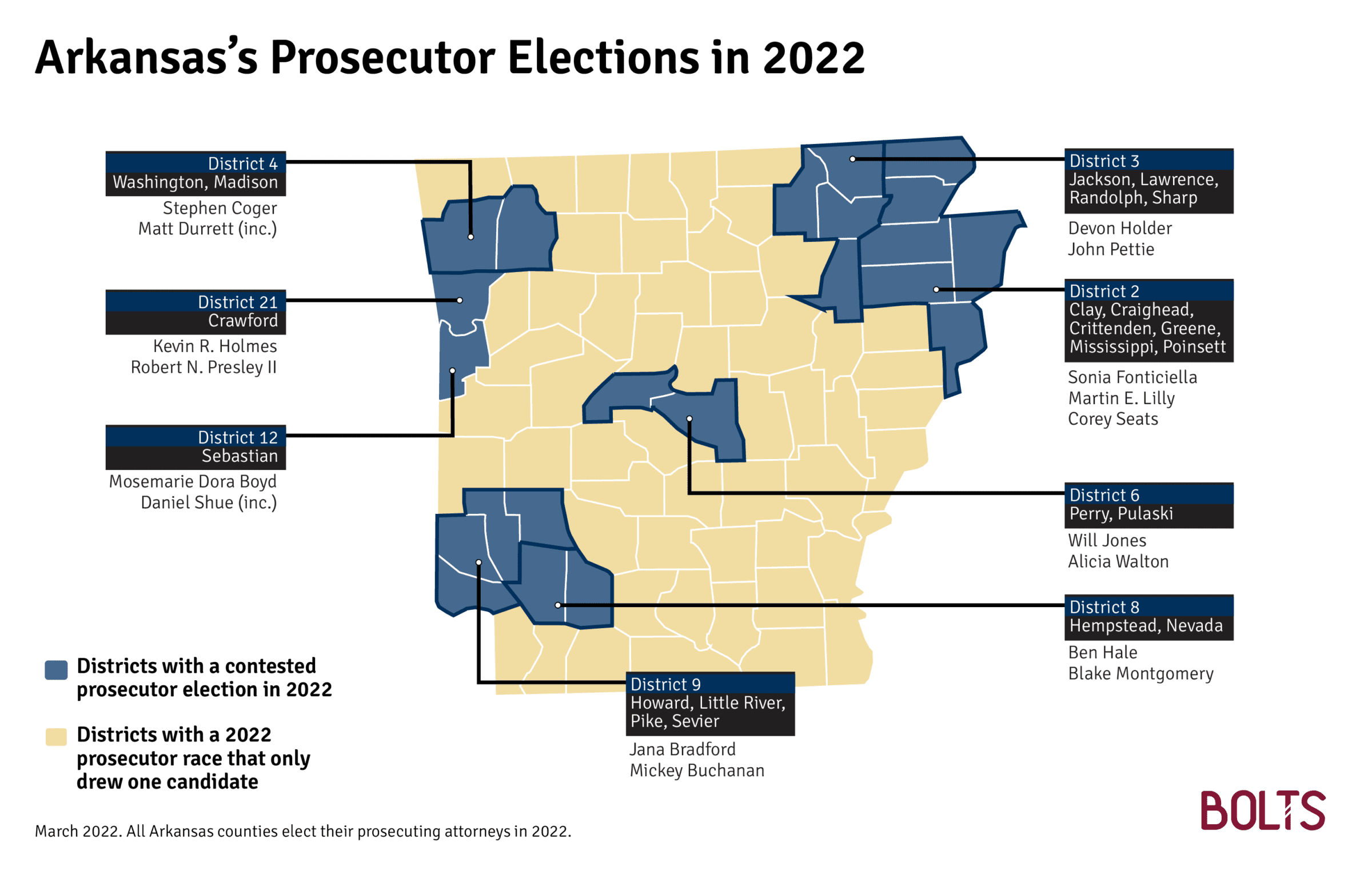

Arkansas

Larry Jegley has been the prosecutor in the state’s most populous judicial district (Perry and Pulaski counties, home to Little Rock) since 1997, and yet he has never faced an opponent—not once, over eight elections. This year Jegley is retiring, and voters will get a choice for the first time in decades. And it may be a historic election: Alicia Walton is running to become the first Black prosecutor in the history of a district whose population is 37 percent Black.

Walton, a public defender, vows to reform what her website calls a “fundamentally flawed” criminal legal system. Her opponent Will Jones is the chief deputy prosecutor in a neighboring district who worked under Jegley for more than a decade.

Another public defender, Sonia Fonticiella, is running for prosecutor in the eastern part of the state, in a district that covers Clay, Craighead, Crittenden, Greene, Mississippi and Poinsett counties. She will face deputy prosecutors Martin Lilly and Corey Seats. And in Northwest Arkansas (Madison and Washington counties), incumbent Matt Durrett faces Stephen Coger, who says incarceration is too high in the district and that he would change bail and jail practices, though Coger also attacks Durrett for being too lenient toward people accused of higher-level crimes.

The state has five other contested races, all in smaller jurisdictions (twenty districts drew only one candidate). The full list of candidates is available here.

These are nonpartisan elections scheduled for May 24.

Nebraska

Each of Nebraska’s 93 counties will elect its prosecutor this year, but stakes are highest in the only two counties with at least 100,000 residents with a contested election.

Both races pit a Republican incumbent against a Democratic challenger who proposes some reforms in counties that went for Joe Biden in 2020. In Lancaster County (Lincoln), County Attorney Pat Condon faces Adam Morfeld, a former lawmaker who founded the progressive organization Civic Nebraska and helped lead efforts to expand Medicaid in the state.

But the state’s premier battle is in Omaha: Douglas County Attorney Don Kleine switched to the GOP two years ago after the Democratic Party accused him of furthering white supremacy; he had brought no charges against the man who killed James Scurlock, a Black protester. In November, Kleine will face Democratic challenger Dave Pantos, the former director of Legal Aid of Nebraska, whose platform is largely centered on reform themes.

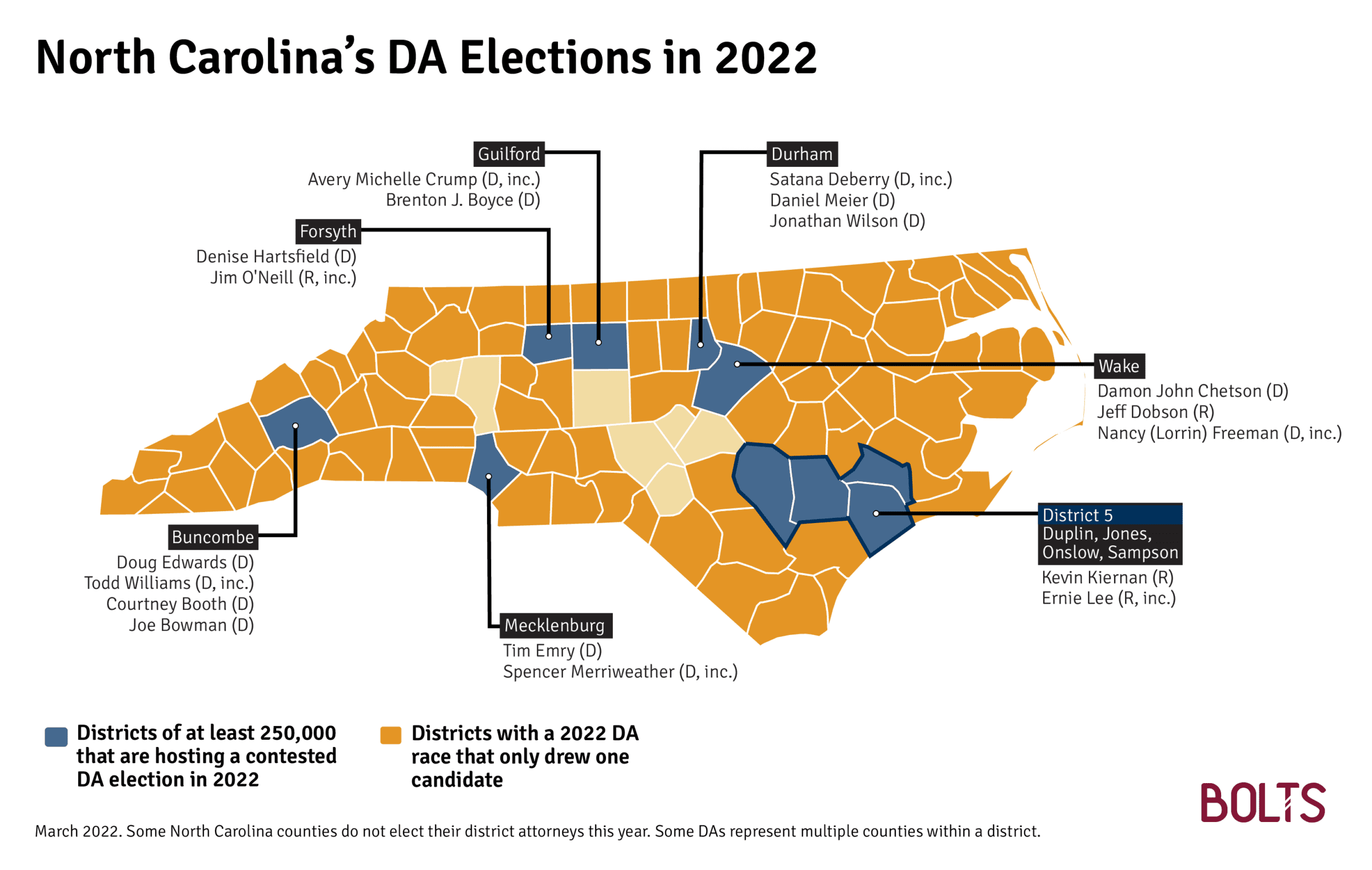

North Carolina

Mecklenburg (Charlotte) and Wake (Raleigh) counties, each jurisdictions of more than one million people, mirror one another this year.

In each, a Democratic DA is seeking re-election but must face a defense attorney in the May primary. In Charlotte, challenger Tim Emry has been part of the local coalition Decarcerate Mecklenburg, which has sought to reduce jail population during the COVID-19 pandemic; he faces DA Spencer Merriweather. In Raleigh, Demon Cheston, whose criminal defense practice involves capital punishment cases, is challenging DA Lorrin Freeman. Cheston and Emry are each running on progressive platforms that include never seeking the death penalty and accountability for police officers who lie or commit misconduct. During the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Charlotte and Raleigh drew thousands of protesters who demanded action against racial injustice and more accountability for the police.

Other populous North Carolina districts are hosting competitive DA elections as well.

In Forsyth County (Winston-Salem), the race will come down to the November general election. In this county that voted for Biden by 14 percentage points, Republican DA Jim O’Neill will face Democrat Denise Hartsfield, a retired judge who is also a former prosecutor and attorney with the Legal Aid Society.

There are also Democratic primaries to watch in Buncombe (Asheville), Durham, and Guilford (Greensboro) counties, though some of the candidates who filed do not appear to be running active campaigns as of publication. In Buncombe, the incumbent faces tough-on-crime attacks from at least one challenger. In Durham, two defense attorneys filed to run against DA Satana Deberry, who has built a reformer profile, rolling out bail reform and clearing thousands of old fines and fees. Deberry testified in Congress earlier this week on behalf of progressive prosecutors. “Stop pretending reform is the real threat to public safety,” she said.

The North Carolina primaries are on May 17th. The full list of candidates is available here.

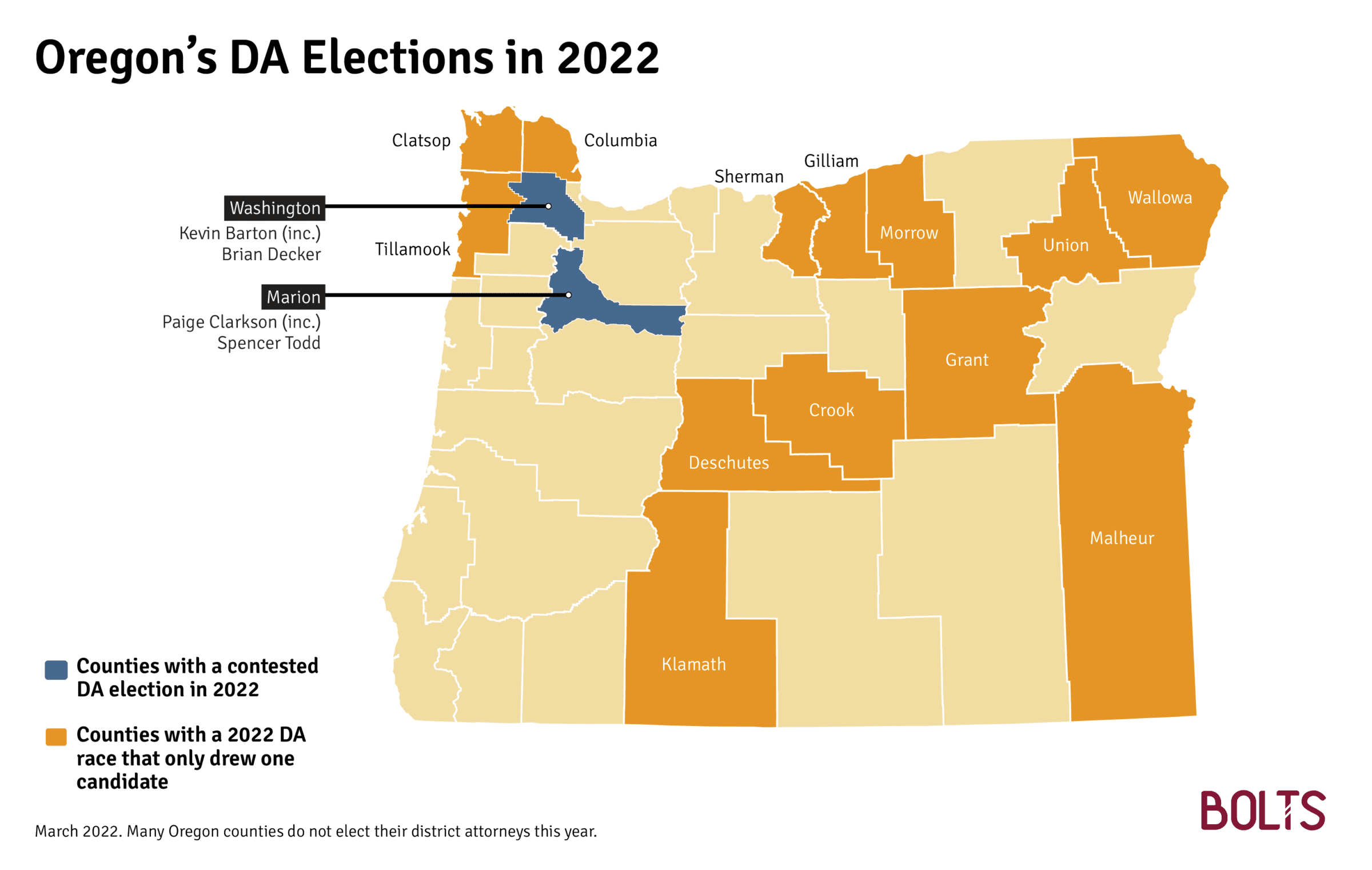

Oregon

Even by low national standards, Oregon has a striking problem with democracy when it comes to its DAs. It has long been marred by a pattern of DAs resigning shortly before their terms conclude—with governors filling the resulting vacancies by appointing deputy prosecutors who then get to face voters as incumbents. That dynamic struck again in 2022, though only in one county. What’s more shocking is that only two elections out of 15 drew multiple candidates.

At least both of those races offer voters a real choice on the direction of local criminal justice policy.

Populous Washington County, right next to Portland, features a clear-cut divide between DA Kevin Barton and challenger Brian Decker, a public defender who is active in various reform drives and advocates for investing in programs that fall outside the criminal legal system. Barton is attacking Decker’s views as “dangerous” and holding up neighboring Portland, which is led by a reform-minded DA, as a boogeyman. (Barton’s 2018 election featured a similar contrast, and he won with some ease after an uncommonly expensive campaign.) Further south, in Marion County (Salem), public defender Spencer Todd is challenging DA Paige Clarkson, saying he wants to turn the page of “tough on crime” policies. Marion County has not had a contested DA race since at least the 1990s.

Oregon’s DAs are notoriously active in opposing criminal justice reform legislation, making these elections meaningful for statewide policy as well. However a coalition of three reform DAs formed in the wake of the 2020 elections, with the new DA of Multnomah County (Portland) banding together with those of smaller Deschutes and Wasco counties to defend reform bills. But the group is set to lose one of its three members as Deschutes County DA Jon Hummel is retiring. He will be replaced by Steve Gunnels, a longtime prosecutor who is the only candidate who filed. (The Multnomah and Wasco DAs are not on the ballot this year.)

Oregon’s DA elections are nonpartisan elections that are scheduled for May 17. The full list of candidates is available here.

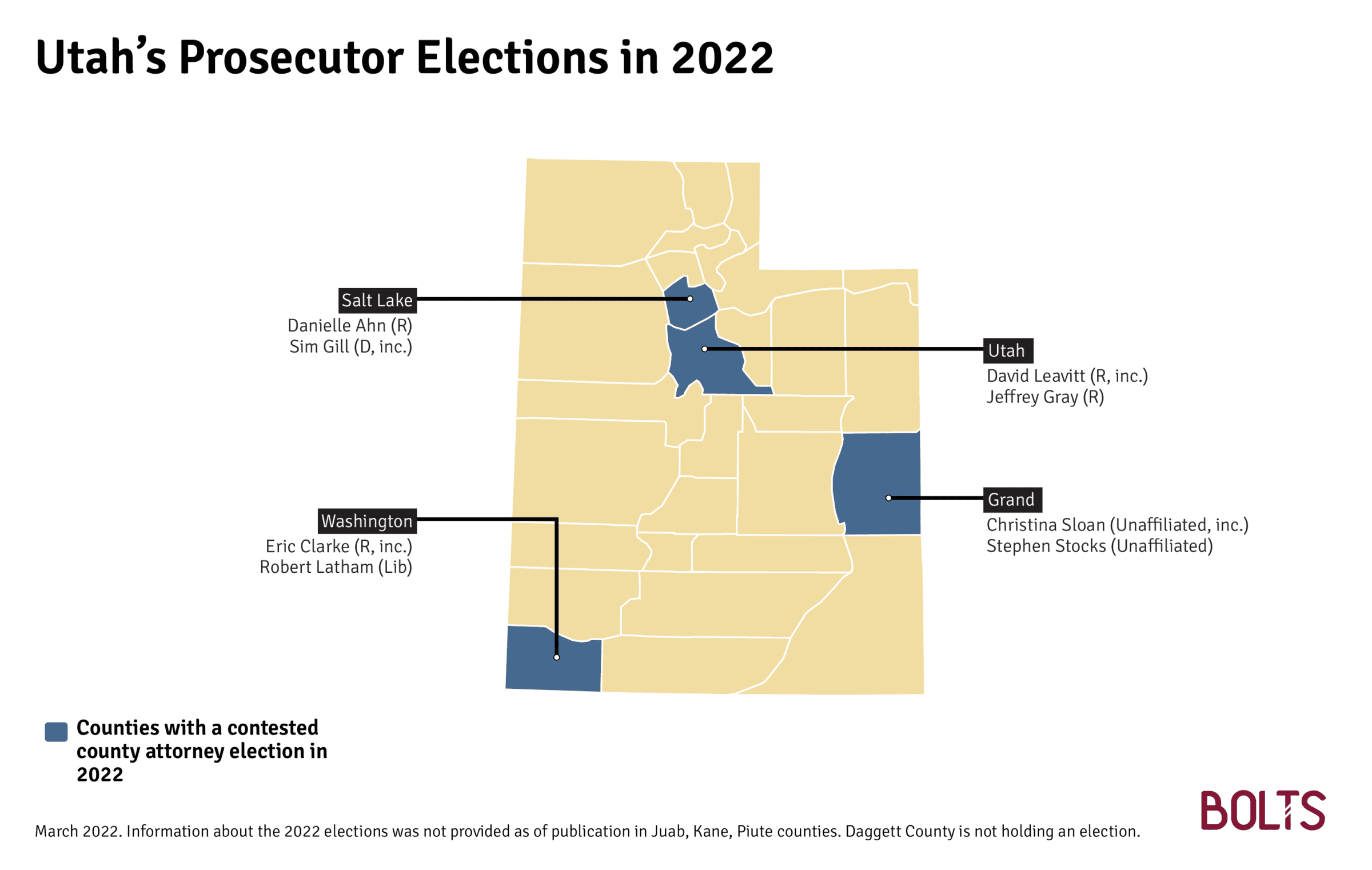

Utah

David Leavitt is the rare Republican prosecutor who grabs headlines for championing criminal justice reform. As county attorney of Utah County, he established new diversion programs after he came into office, and last fall he announced he would no longer seek the death penalty. “It simply demonstrates our societal preference for retribution over public safety,” he said of capital punishment in a public release.

Leavitt’s re-election race will test the GOP’s appetite for such changes. He faces Jeffrey Gray, an assistant Utah solicitor general who touts his ties to law enforcementand promises to bring back the death penalty if elected.

Over in Salt Lake County, Democratic prosecutor Sim Gill triggered a national furor during the Black Lives Matters protests of 2020, filing gang enhancements against protesters accused of spilling red paint in front of his office, which threatened sentences of up to life in prison (the charges were later amended). Protestors were criticizing Gill’s decision to decline charges against officers who killed 22-year-old Bernardo Palacios-Carbajal earlier that year. But Gill is in relatively good shape in his reelection bid this year; he drew no challenger in the Democratic primary, which can be decisive in this blue-leaning jurisdiction. Republican challenger Danielle Ahn has no campaign website or campaign account as of publication.

Utah only has two other contested prosecutor races: one in Washington County where a GOP incumbent faces a Libertarian challenger, and one in the very sparsely populated Grand County.

The primaries will be held on June 28, followed by the November general elections. The full list of candidates is available here.