‘The Arpaio of the East’ Faces His First Opponent in 12 Years. Is Anyone Watching?

Thomas Hodgson, the longest-serving sheriff in Massachusetts, is infamous among jail watchdogs for dangerous conditions, medical neglect, malnutrition, and mounting suicides.

Alex Burness | October 31, 2022

The official line was that Mark Trafton’s suicide came out of nowhere.

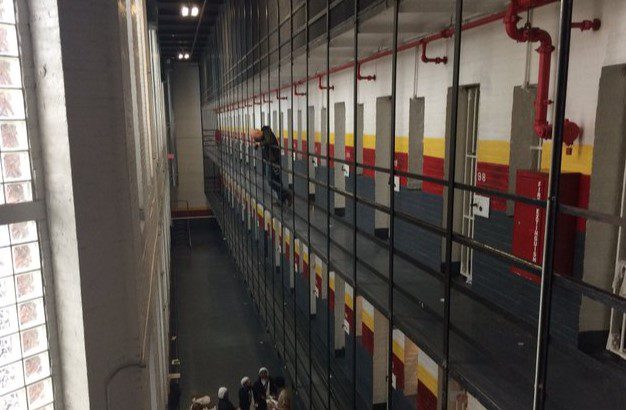

A guard found Trafton hanging in his cell just before 5 a.m. on May 3, 2019, inside the Ash Street Jail in New Bedford, a city by the bayline in Bristol County, southeast Massachusetts. He was 59, pronounced dead the same day he was set to appear before a judge in a rape case.

This wasn’t an unusual scene in Bristol County, where at least 22 people have taken their own lives while in jail since 2006. Lawsuits against the sheriff’s office, which runs the local lockups, have for years alleged the kind of degrading conditions and neglect that can increase the risk of suicide behind bars.

The local news made Trafton’s death sound unavoidable, writing that he’d indicated no suicidal ideation when meeting earlier that week with a mental health profressional and his attorney, and that he did not “exhibit any suicidal behaviors or statements since he arrived in custody” in September of 2018. The New Bedford Guide quoted Tom Hodgson, the Republican sheriff in charge of the jail since 1997, who offered condolences to Trafton’s family and said, “we’re keeping not only them but everyone involved in this incident in our prayers.”

But Richard Saunders, who was incarcerated with Trafton at the Ash Street Jail, told Bolts that Trafton was obviously suicidal and spoke often of killing himself. Through tears, Saunders recalled how others incarcerated with Trafton worried he would act on the threats—and said at least three people warned guards about it—when he scribbled suicidal thoughts on the wall in his cell, and started calling a drawstring from his laundry bag his “hanging rope.”

Saunders said he was horrified, but not surprised, when he heard guards rush into Trafton’s cell before dawn, then the beeping and static crash of a defibrillator before he saw his friend whisked out under white cloth.

Hardly two months passed before another person died by suicide in another Bristol County jail—again portrayed as an unavoidable tragedy, with Hodgson telling the local news, “There was absolutely no indication to anyone. This was a shock.”

Jail suicides under Hodgson have long been shown to surpass those in other counties. According to a statewide review of jail suicides in Massachusetts by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting, Bristol County, home to about 8 percent of the state’s population, accounted for nearly a quarter of its jail suicides between 2006 and 2016.

Lawsuits and protests over dangerous jail conditions, malnutrition and medical neglect have made Hodgson infamous among many jail watchdogs.

“He’s earned the nickname ‘The Arpaio of the East’,” said Elizabeth Matos, executive director of Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts, referencing Joe Arpaio, the rightwing strongman and former sheriff of Maricopa County (Phoenix), Arizona, whose brutal jails and discriminatory policing practices were so egregious as to earn him unusual national scrutiny and a criminal conviction.

“I don’t know why he’s not as famous as Arpaio,” Matos said of Hodgson in Bristol County. “But he should be.”

There are plenty of similarities: Both are staunchly anti-immigrant strongmen deeply embedded in far-right networks. Both support the movement of “constitutional sheriffs,” which preaches that sheriffs have ultimate authority within their counties. Both tied themselves closely with Donald Trump once he came to power in 2016. And both are also known for scandals and inhumane treatment inside their jails, and have faced heaps of lawsuits over dangerous conditions.

“Jail shouldn’t be a country club,” Hodgson has said, a longtime mantra that nearly mirrors an infamous Arpaio catchphrase.

Hodgson, Massachusetts’ longest-serving sheriff, is again seeking re-election on Nov. 8. He has defended his oversight of the jail, including releasing his own internal report on jail suicides that absolves his department of responsibility while ignoring key details. He has pushed back against a state probe into his jail practices, calling it a “political witch hunt.” After the most recent suicide on his watch, earlier this month, Hodgson said his staff had gone “above and beyond” to help the man, and should be applauded.

There are no consistently Republican counties in Massachusetts, but Bristol County, where Trump claimed 43 percent of the vote in 2020, is widely considered to be the state’s most conservative. Hodgson’s Democratic opponent Paul Heroux, the mayor of Attleboro, a small and largely working-class city near the state’s Rhode Island border, is running with support from the state’s Democratic establishment. His campaign recently released an internal poll showing him within two percentage points of Hodgson.

Heroux, who is Hodgson’s first election opponent in twelve years, criticized the sheriff’s treatment of incarcerated people. “How can anybody say that’s a good idea, to have this type of person, with his mindset, being our chief jailer?” he said.

But Heroux added he has struggled to rally interest since entering the race in January. “A lot of people told me this race would get national attention,” Heroux told Bolts in mid-September. “I was told I was going to get a million dollars in my campaign account from donations all over the country. … Right now, I’m struggling to raise money. People don’t really care about a sheriff.”

Hodgson was appointed sheriff in 1997 by Governor William Weld, a Republican who compared himself to Attila the Hun on crime issues, and said prisoners should be made to break rocks. Since then, he has won re-election four times, most recently in 2016 in an uncontested race.

In his more than two decades in power, Hodgson has worked to build a brand as a tough-on-crime community protector. The responsibilities of sheriffs in Massachusetts, unlike in many states, are largely limited to overseeing jails; they do not have regular patrol or arrest duties. But Hodgson has repeatedly sought to have his office patrol the county, drawing pushback from local officials. In 2003, for instance, he declared New Bedford a “killing field” and sent his deputies to “the troubled areas” of town. The mayor asked a judge to block Hodgson’s patrols in the city while the district attorney at the time publicly criticized the sheriff’s plan, telling the Boston Globe, “You can’t have the guy who was serving mashed potatoes to inmates last week calling himself a drug detective this week.”

Matos, who grew up in Bristol County as Hodgson rose to power, says the sheriff has a charming public persona that belies the callous indifference to human suffering that occurs inside his jails. Dangerous conditions and far-right politics are common in American sheriff’s offices, but Matos, who has helped sue jails and prisons across Massachusetts, said conditions inside the Bristol County jails stand out. “Folks who are incarcerated who we’ve interviewed consistently say that (Bristol’s) is by far the worst they’ve ever been in,” she said. “It’s intentionally dehumanizing.”

Matos’s organization is currently suing Hodgson in a state court on behalf of three people with mental illness who allege they were placed in solitary confinement inside Bristol County jails with little treatment for their conditions. The suit accuses the sheriff of tolerating an “alarmingly high” suicide rate—twice that of other Massachusetts county correctional facilities and three times the suicide rate for jails nationally, according to the lawsuit—and argues that “harsh and humiliating” jail policies “discourage prisoners from reporting thoughts of self-harm or suicide.”

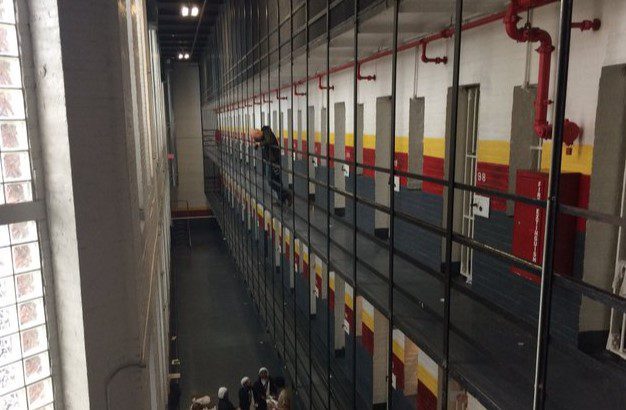

The lawsuit also alleges squalid conditions in solitary confinement. “Prisoners describe a pervasive stench when disturbed prisoners flood their cells and their floods with human waste,” it states. “All too often, correctional staff respond to such events with verbal or even physical abuse.” The suit says people confined to solitary are allowed outside their cells for only about five hours per week, for recreation “alone in small pens resembling dog cages.”

Hodgson declined through spokespeople to be interviewed for this story and didn’t respond to written questions from Bolts. The sheriff, who on his podcast once said, “I never, have ever, denied any outlet an interview, … because I felt like I’m in a public position, I have an obligation to answer,” has suggested that people who complain about treatment in his jails are liars. He told The Boston Globe in response to the solitary confinement lawsuit, “Surprise, surprise, we might have people in our facilities who are not telling the truth.”

Hodgson has also pushed back against critics by citing his department’s stellar ratings from accreditation inspectors at the American Correctional Association. But Matos said that people incarcerated in the Bristol County jails tell Prisoners’ Legal Services the inspections are easy to pass. “We have heard consistently that there is plenty of notice when inspections happen, and incarcerated people almost always know because things are suddenly getting painted and patched,” she told Bolts. “Then things go back to normal after the dog-and-pony show.”

Saunders said he was scared to speak up when inspectors came by. “You want to talk to them, but they’re walking with lieutenants and you know that if you say anything, you’re going to the hole,” he told Bolts. “And they (the inspectors) don’t even look in the cells. My ceiling was falling down. The mice had eaten into my ceiling, and there was mold. There’s toilets coming off the wall. There was an opossum that came through. They didn’t look in.”

Saunders, who was released from the jail earlier this month, said that he experienced extreme temperatures during his four years at the Ash Street Jail; he said his cell, which was near an open door to the building, once started to fill with snow. He said the food was barely edible and often comprised mostly carbohydrates like unseasoned, nearly raw potatoes, meant to meet minimum calorie standards without providing much nutrition. “Everyone gets a belly in there,” Saunders said. “Even the guys who work out seven hours a day.”

Saunders said the plumbing at Ash Street often fails, with pipes bursting regularly. He recalled one time feces exploded from a pipe into a living area. He remembered the solitary confinement cells being even worse. “There’s feces rubbed on the walls,” he said. “Nobody cleans it. They throw you in there and they disrespect you. They don’t give you your property.”

Kellie Pearson said she recalls her former partner, Michael Ray, describing extreme medical neglect at the Bristol County jail campus in Dartmouth. He once suspected he had a staph infection, she said, and called her inconsolably upset: “He said, ‘Kellie, I’m worried I’m going to die and they won’t listen to me. They gave me a cream, they told me it was like a bug bite.’”

Pearson said she tried every phone number she could locate for the jail, and finally, after threatening to sue and to whistle-blow in the press, she convinced a nurse to call him down for treatment. “When they checked him he needed to be rushed to hospital,” Pearson said. “The doctor told him that he might have died if he hadn’t come in.”

Ray’s incarceration ran almost two years, before he hanged himself in his cell in 2017. Pearson unsuccessfully sued Hodgson in 2018 over the high cost of phone calls from jail, explaining that the financial stress inhibited Ray’s ability to communicate with her.

Stories like these abound in Bristol County. The Standard-Times of New Bedford reported in 2018 that people incarcerated in Bristol were receiving no fresh fruits or vegetables—until the newspaper began investigating, at which point the sheriff’s office “changed its policy to allow each person two apples a week.”

People detained there have mounted hunger strikes to protest lack of medical care, overpriced commissary items and unsanitary facilities. And lawsuits against Hodgson piled up to the point that Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey called for a state investigation into his office in 2018.

“Recent lawsuits have raised serious allegations about the conditions of confinement at Bristol County jails,” Healey wrote in a letter to state law enforcement officials. “ Among other things, these lawsuits allege that inmates with mental illness are routinely segregated for unreasonably long periods of time, exposed to unnecessarily harsh conditions, and denied access to basic programs and services.” She said the lawsuits were consistent with complaints her office had received about “inadequate mental health screening and treatment, denials of medical care, overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, poor nutritional services.”

In December 2020, Healey’s office released a long report detailing civil rights violations committed under Hodgson against immigrants detained at his department’s Dartmouth campus. It investigated a clash early in the COVID-19 pandemic between staff and detainees who were scared of how they would be treated in quarantine and refused to be removed from their units.

According to the report, one detainee said that Hodgson personally shoved him while he was phoning his attorney, an allegation Hodgson has denied. The report says that the scene dramatically escalated as Hodgson’s staff overwhelmed detainees with dogs and so much pepper spray that two men were hospitalized and another needed an emergency procedure, performed in the jail, to be revived. After he was revived, Healey’s office wrote, the man “was not taken to the hospital for a medical evaluation or assessment, but was instead placed in solitary confinement.”

Prior to the incident, Hodgson had multiple partnerships with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. One was a contract to detain immigrants in ICE’s custody; the other was membership in the 287(g) program, which deputizes local law enforcement to act on ICE’s behalf within jails. A staunch defender of ICE detentions, Hodgson has repeatedly traveled to Washington, D.C., to champion stricter immigration enforcement, and he once offered to send Bristol County detainees to the U.S.-Mexico border to help build Trump’s wall.

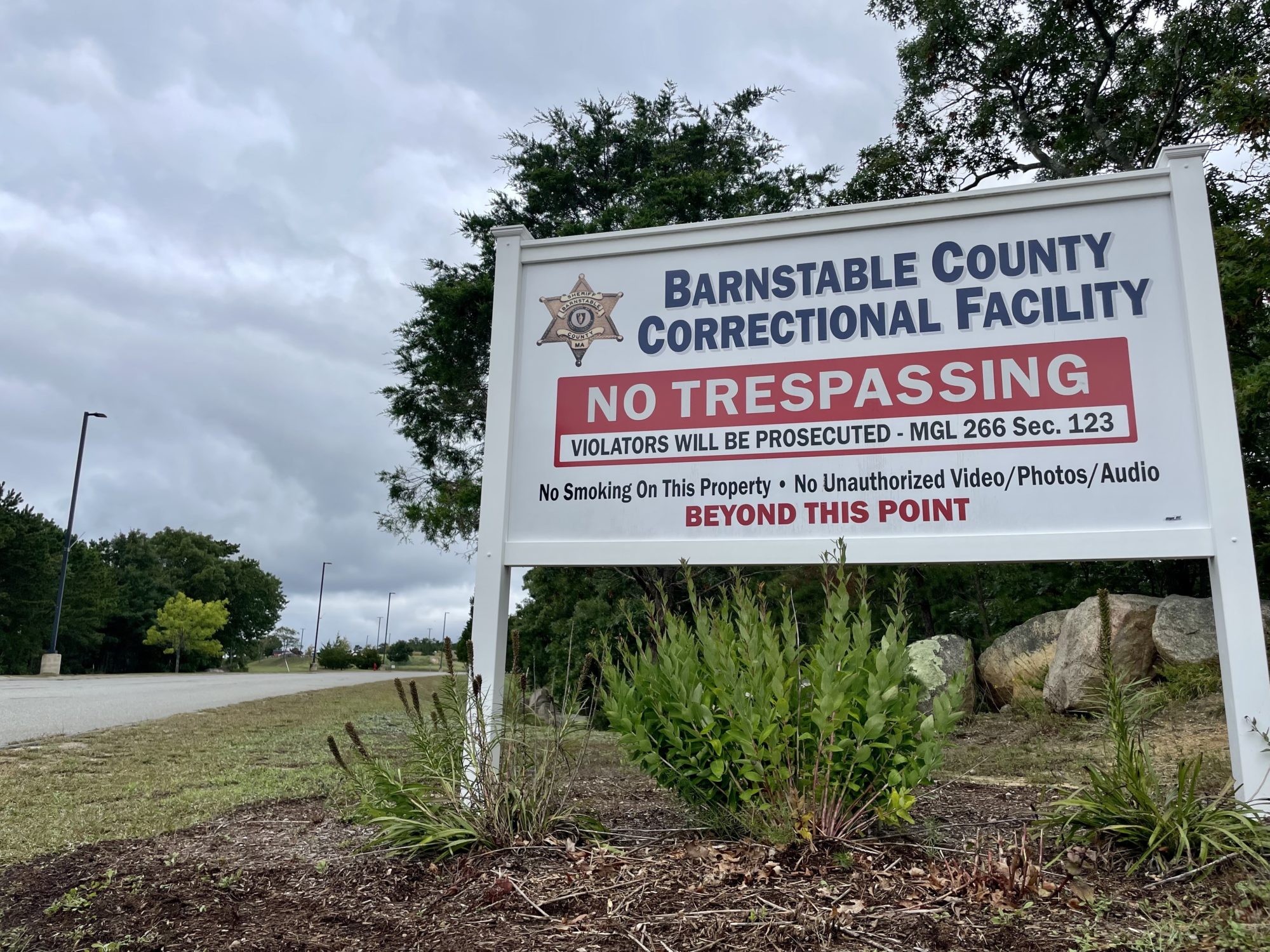

But the attorney general’s investigation in 2020 found that Hodgson’s staff had shown “deliberate indifference” to the safety of detained immigrants, and recommended that the federal government break off its partnerships with him. The Biden administration agreed, terminating the 287(g) and detention contracts last year. (Neighboring Barnstable County, home to Cape Cod and immediately to Bristol’s east, is now the only county in all of New England involved in 287(g).)

Albert Orlowski, a retired longtime deportation officer with ICE and a Dartmouth resident who says he advised Hodgson’s staff on immigration enforcement, described Hodgson as unprofessional and unreliable in an interview with Bolts. Orlowski aired some of his criticism in the local press in 2017, and Hodgson replied by accusing Orlowski of lying about their prior relationship.

“You do not use tear gas on detainees. You do not use canines,” Orlowski told Bolts about the 2020 events. “If you go into a facility, which is a closed environment, and you throw tear gas and send in barking, vicious dogs who are trained to react, how do you think people are going to behave in that situation?”

The man running to unseat Hodgson calls his jails revolting and inhumane, arguing that people under the sheriff’s custody deserve better medical care and services.

“His attitude is to make life miserable for you,” Heroux said. “My attitude is that we’re going to address your needs, your drug addiction, mental illness.” He also vows to increase the transparency of the office.

A report released this year by a special commission on correctional funding convened by the Massachusetts legislature found that Bristol County spends far less on programming for detainees than the other eleven counties studied, and roughly a third as much as the next highest county. In 2017, the New England Center for Investigative Reporting found that Bristol had just three mental health clinicians for a jail population averaging about 1,350 people; by comparison, Hampden County (Springfield) had ten for roughly the same average jail population.

Saunders told Bolts that few efforts are made to help the people detained in Bristol County—almost all of whom are there pretrial, and will eventually reintegrate in the community—prepare for release. “There is absolutely zero success stories, and everything Hodgson says is a lie,” Saunders said. The sheriff’s office lists dozens of programs, ranging from religious meetings to vocational classes. “There is no such training. There are no programs available,” said Saunders, who added that most people locked up in Bristol County spend at least about 21 hours a day in their cells.

Pearson similarly told Bolts that she never heard her former partner mention being involved in a single program while he was locked up.

Hodgson has blamed his office’s lack of investment in jail services on state funding, while also bragging that he’s simply good at cutting costs and saving taxpayer money. Court documents show his office has collected millions in kickbacks from Securus Technologies, the private company that charges incarcerated people to make phone calls. He also spent at least about $2 million early in his tenure on a “homeland security force,” even though he has little authority beyond his jails—the money reportedly covered a $500,000 “mobile command center,” and a set of miniature fire trucks and police cars meant for simulations of terrorist events.

In conversation with Bolts, Heroux did not detail many policy changes he would make to improve conditions at the jail. Asked about local advocates’ longtime push to close the jail on Ash Street, Heroux did not stake a position, other than to say he’d be wary of shutting it down without first freeing up new bed space somewhere else. He also did not name any offense for which people are presently jailed that he believes should not carry jail time; more reform-minded figures in the state have tried to move Massachusetts away from arresting and incarcerating people for drug offenses and other actions typically deemed “low-level.”

Heroux also said that he is “indifferent” toward the 287(g) program, though he added that he feels local law enforcement should not do the federal government’s job. He said he “would entertain it” if ICE made any request of him, including if it asked him to share information on detainees or to keep people detained past their release dates.

Asked about the push to make phone calls from jail free, Heroux initially was under the false impression that the legislature already eliminated those costs. But a legislative proposal died earlier this year, after heavy pushback from the state’s sheriffs. Once corrected, Heroux added that the issue called for legislative action so that the costs are incorporated into the state budget. “We shouldn’t obstruct an inmate’s ability to call home to stay in contact with friends and family,” he said. Massachusetts sheriffs in 2021 jointly announced they would cap the cost of phone calls but opposed making them free; Hodgson himself has fought a lawsuit to eliminate fees in Bristol.

Heroux is backed by local activists who have organized against Hodgson for years, penning endless guest columns in local media, publishing deep opposition research and staging protests. Several activists told Bolts that it’s been hard to get voters to care about abuses at Hodgson’s jails.

“The average person doesn’t want to know what brought somebody to jail. Their attitude is, you made your bed, it’s not my concern, you did this to yourself,” said David Ehrens, a member of the citizen group Bristol County for Correctional Justice and a prolific anti-Hodgson writer.

Everytown for Gun Safety, an organization founded by Michael Bloomberg, began digital advertising against Hodgson earlier this month, NBC News reported.

Pearson, the former partner of Michael Ray, is among those Bristol County residents who cannot afford to ignore the topic of jail conditions. As a mental health clinician, Pearson told Bolts that she is well positioned to understand that Ray should have received special care when in jail. She spoke of his lengthy history of mental illness history and of another suicide attempt years before he was locked up in Bristol County.

Never far from her mind is something Ray wrote to her in a letter before he took his own life in Hodgson’s custody: “If something happens to me, I want people to know I’ve been getting no help.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.