Massachusetts Candidates Run for Sheriff as Outsiders to Law Enforcement

A social worker and a nurse are challenging incumbent sheriffs in Tuesday’s primaries and pushing a new approach to managing local lockups, the primary responsibility for sheriffs in the state.

Alex Burness | September 2, 2022

Voters might imagine a badge and gun when they think of sheriffs, perhaps even a cowboy hat and horse, but in Massachusetts they usually don’t patrol their counties. Sheriffs are mainly tasked with running their local jails, with little oversight, and monitoring the people locked inside.

Most sheriffs in the state are still longtime cops. But this year there are several candidates running without a police background, and some are proposing a different approach to the job and arguing for better treatment and care of incarcerated people and their families.

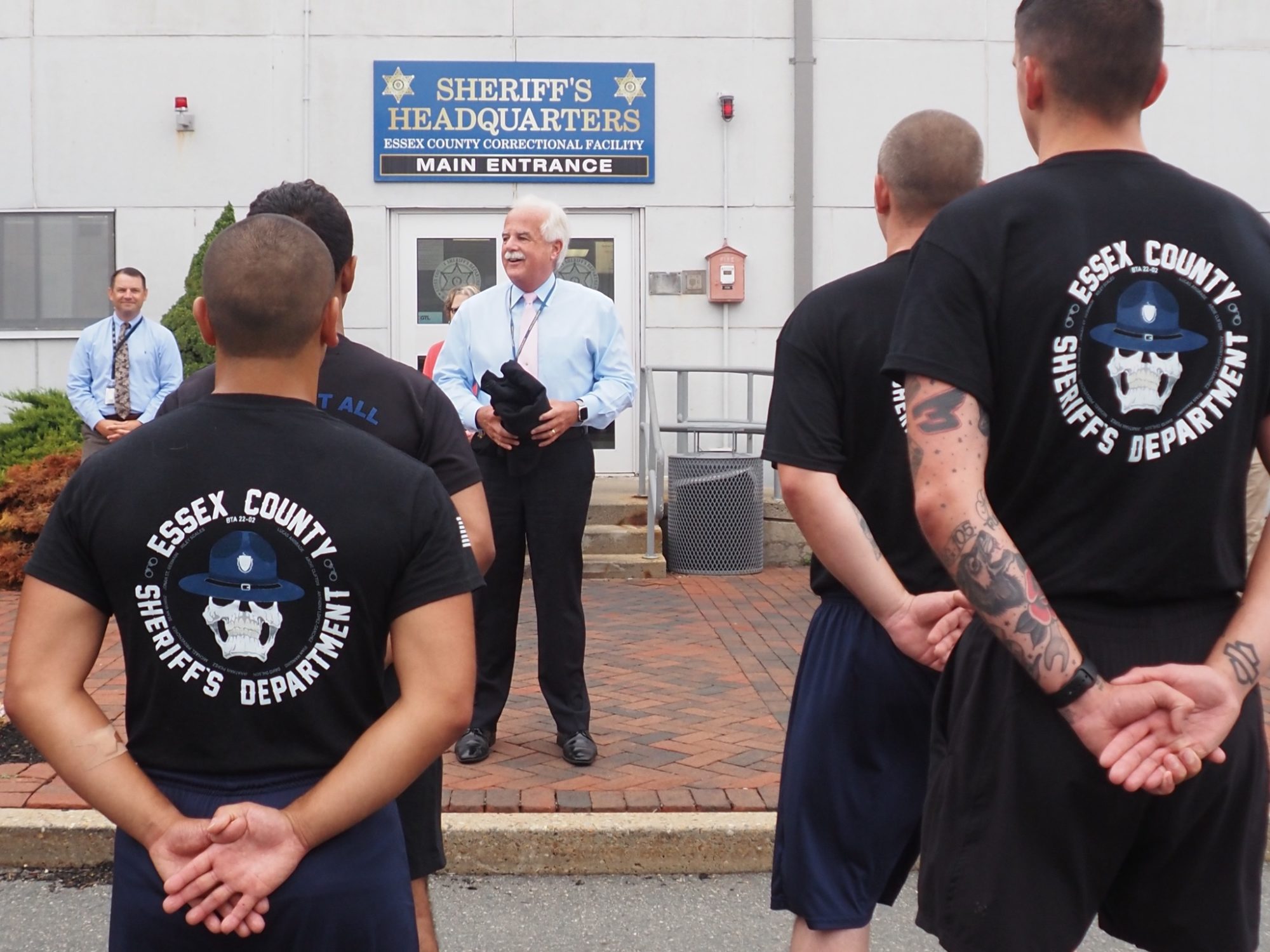

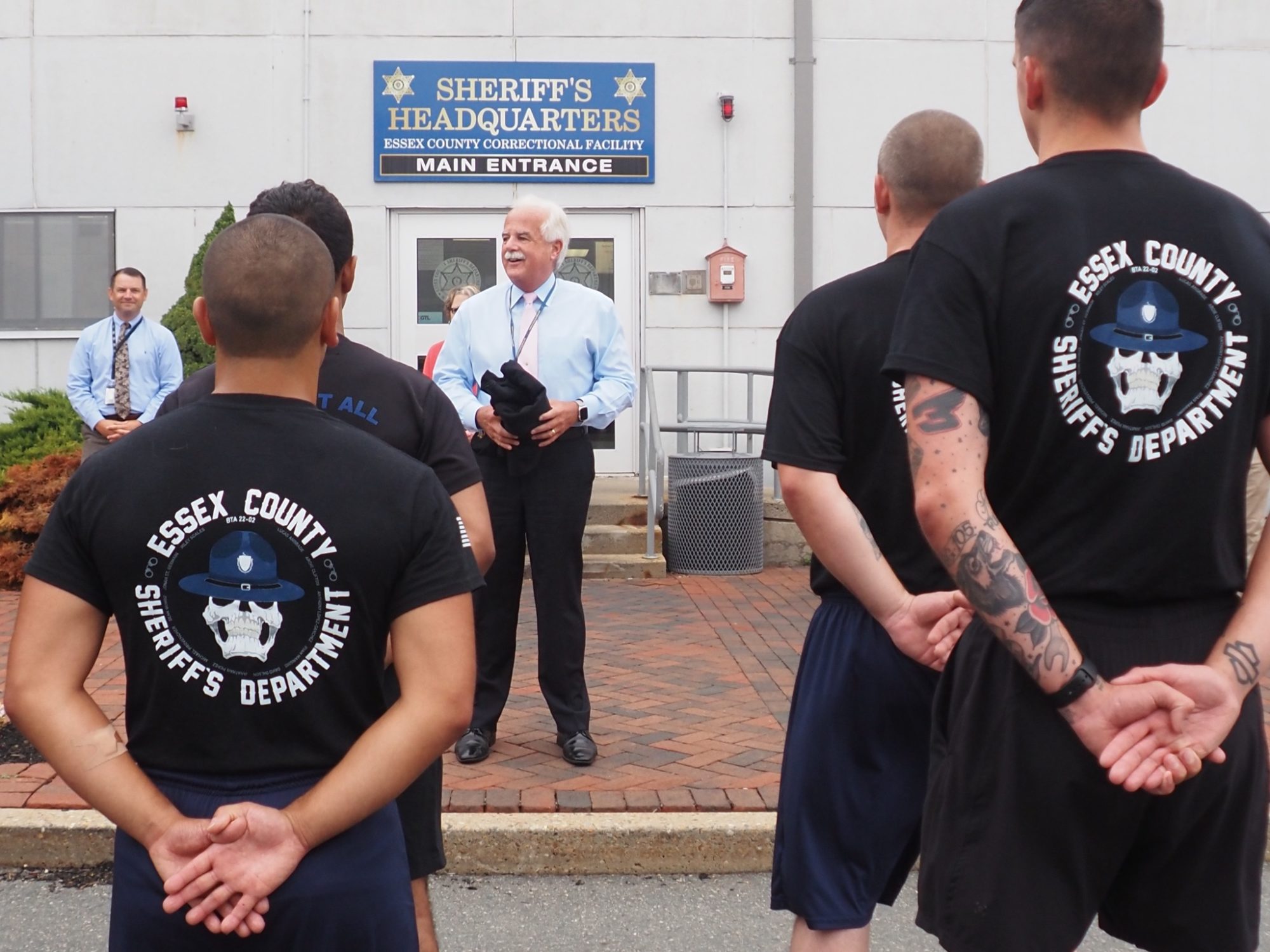

Virginia Leigh, a social worker who is challenging incumbent Essex County Sheriff Kevin Coppinger in the Sept. 6 primary, told Bolts she would try to make the county jails into “clinical, trauma-informed” spaces, where family contact is free and happens more often. She has worked closely with incarcerated people in both Massachusetts and Mexico.

The Essex sheriff “is responsible for prisoners’ care, treatment, well-being, rehabilitation and ultimately successful re-entry into the community,” said Leigh, who seeks to run one of the state’s largest jails. “This is human services work.”

Some states require their sheriffs to have backgrounds in law enforcement, which boxes out candidates who may want to take over the office from outsiders. This has been an impediment to reform in California, advocates have argued.

But even where statute allows greater candidate pools, as a general rule, non-cops don’t win these seats.

Out of some 3,300 sheriffs in the U.S., “you could probably count on two hands” those without law enforcement experience,” said Max Rose, executive director of Sheriffs for Trusting Communities, an organization fighting jail expansion and racist, anti-immigrant policies within sheriff departments.

“The status quo of the sheriff, as we see with a lot of sheriffs in Massachusetts, is regressive and incompetent, and uses their power at the legislature to fight things like free phone calls” to and from people in jail, Rose said.

Massachusetts has for years debated whether to make phone calls free, amid a body of research showing that restricting phone contact—a service that, in many parts of the country, currently produces revenue for profit-driven telecommunications companies and kickbacks for government agencies—inhibits successful re-entry to free society after jail and prison.

These calls are now capped at 14 cents per minute in Massachusetts, which adds up; one woman told the Boston radio station WGBH that she works three jobs and spends $300 a month on phone calls to her incarcerated husband. She said her family has “cut back” on calls to limit spending.

The latest legislative effort to fund free calls from prisons and jails fizzled in July at the end of this year’s session. Some sheriffs raised concerns about the costs of the proposals.

Leigh said that as sheriff she would not wait on lawmakers to make phone calls free.

“If you have somebody who has major mental illness and you look at what one of the most important factors is in determining whether that person is able to live a full and successful life … it’s whether or not that person has family in their life,” she told Bolts.

Leigh noted that her incumbent opponent, Coppinger, accepts campaign donations from representatives of Securus Technologies, the company that provides and profits off of these calls in her county and many others. A recent report by the nonprofit Common Cause documents the contributions by Securus representatives to multiple state sheriffs. (Coppinger did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story.)

Coppinger, a Democrat like Leigh and most elected officials in Massachusetts, has been slow to modernize his office. He initially resisted medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for people incarcerated in his jail, until he was sued for denying it and a judge forced him to allow methadone for a man serving a minor sentence. In his re-election campaign, Coppinger now praises the treatment option a court forced him to permit.

Leigh says her priority in office would be to improve rehabilitation efforts, promising to dramatically increase treatment, educational and professional programming options inside the jails. She also wants to strengthen support for people who’ve already re-entered free society after being incarcerated in Essex County.

Massachusetts reformers in recent years have pushed to repeal a state statute that enables courts to involuntarily detain people in a jail or prison to receive substance use treatment, making the case that incarceration is harmful to public health. Leigh agrees with harm-reduction experts who say treatment should be free and widely available in communities, not something to be accessed once a person has been locked up. But she also said she has to work with the system that exists.

“I’m a social worker, so my training is to not try to force a system to be something that it’s not,” Leigh told Bolts. “My clinical training tells me I need to meet people where they are.”

Jail can be a dangerous place for someone struggling through withdrawal, with some dying while receiving little medical care. A jail or prison stint can also carry a higher risk of overdose upon release because of lowered opioid tolerance.

Caitlin Sepeda, a nurse with many years of experience working in jails, is challenging incumbent Hampshire County Sheriff Patrick Cahillane in Tuesday’s Democratic primary. She says that local lockups need to revolve around treatment so long as they continue to be a dumping ground for sick and vulnerable people. She pointed to state data showing that 60 percent of the more than 100 people incarcerated in Hampshire County receive a substance use diagnosis. Nearly half are diagnosed by the jail as having severe mental illness; 70 percent self-report severe mental illness.

“Those are not law enforcement issues,” Sepeda told Bolts, “Those are nursing issues. Those are social service issues.”

Sepeda also argued that in addition to comprehensive health care, people locked up in Hampshire County need greater connection to the outside world. That means modernized vocational and educational options to better position people for employment after incarceration, which she says are currently lacking at the jail.

Also running in Hampshire County’s Democratic primary is Yvonne Gittolson, who worked as education coordinator in the local jail until last year, and is now proposing to reinforce educational programs to facilitate re-entry. No Republican is running for sheriff in either Essex or Hampshire, so the Democratic primaries on Tuesday are virtually certain to decide the next sheriff.

Anyone in the state trying to unseat an incumbent sheriff this year faces steep odds in part because of how little attention people pay to the office. Eighty-three percent of respondents couldn’t name their sheriff in a poll conducted by Beacon Research and released by the ACLU of Massachusetts this spring. Ninety percent didn’t know that sheriffs in that state serve six-year terms, and 41 percent didn’t even know that sheriffs are elected in the first place.

“People just aren’t paying attention,” said Laura Rótolo, field director for the ACLU of Massachusetts. “They know very little about the position in general, and even less about the candidates.”

In 2016, the last time the state’s sheriff offices were up for election, only four of the 10 incumbents who sought reelection faced challengers and none lost their seat. State elections data show the average margin of victory for Massachusetts sheriffs in contested races has never been lower than 33 percent in any of the last three major cycles.

But things have changed this year, with eight races contested in either or both the primary election or the general. The uptick in challengers follows protests over law enforcement accountability, Trump-era political activation and, more recently, the state ACLU launching a “Know Your Sheriff” educational campaign.

Tuesday evening marks the close of the Massachusetts primary, one of the last in the country this year. Five sheriff candidates are women, and, given that all Massachusetts sheriffs and some 98 percent of sheriffs nationwide are men, it would be statistically and historically significant if even one were to win.

Even if this isn’t their year, Leigh and Sepeda hope, at minimum, that the public is starting to wake up to the critical role that sheriffs play. Recent advocacy has also targeted Massachusetts sheriffs’ power in denying ballots to eligible voters in jail and their cooperation with ICE.

“I think for so long—particularly in Massachusetts, where the sheriff is a long-term position, six-year terms—there’s very little oversight to the job,” Sepeda said. “The sheriff is accountable pretty much only to the voter. And usually the voter doesn’t hear what goes on at the facility and only hears when something is drastically wrong. I’d argue that hearing nothing doesn’t mean everything’s OK.”

The article has been updated with more information about the candidates.