Cape Cod Will Decide Whether to “Rip Up” Agreement for ICE Collaboration

Barnstable is the only county in all of New England that has contracted in ICE’s prized 287(g) program. The upcoming sheriff’s race will test the relationship.

Alex Burness | September 30, 2022

This article is part of a series on how the midterms may reshape immigration policy. Read our previous installments on Wake County, North Carolina, and Frederick County, Maryland.

Editor’s note (Jan. 7, 2023): Donna Buckley won the sheriff election on Nov. 8, and she terminated the Barnstable County contract with ICE on Jan. 4, her first day in office.

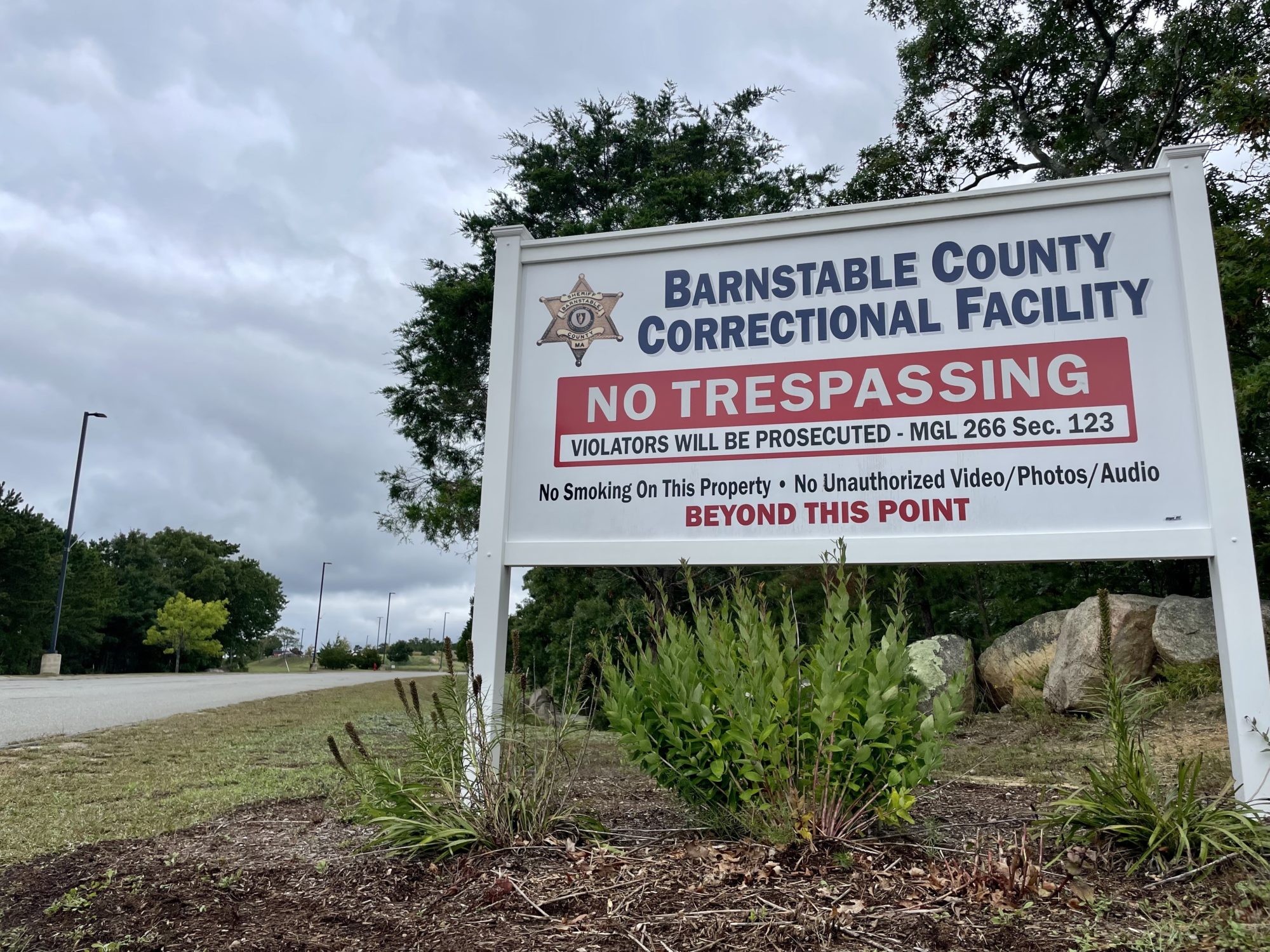

Barnstable County, which comprises Cape Cod, Massachusetts, is known for its beautiful coastal scenery, busy summers and snug, sleepy off-seasons.

Ron DeSantis, Florida’s Republican governor earlier this month sent about 50 Venezuelan migrants on a plane to Martha’s Vineyard who were then promptly transferred to Cape Cod. Local politicians decried the stunt as a cruel attempt to expose the area’s immigrant-friendly self-image as fraudulent, but refused to take the bait. “We are going to take care of these people,” state Senator Julian Cyr, a Democrat, told reporters. Articles about the open-armed response abounded.

But Barnstable also has another distinctive feature: an unusually tight relationship with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

It is the only county in all of New England that has an active contract with ICE’s 287(g) program. This program, which is typically up to sheriffs to opt into, deputizes local officers to assist ICE in sharing data about, questioning, and detaining people suspected to be unauthorized immigrants.

“It just makes everyone feel worse, afraid. Afraid to be deported any time,” Katia Regina Dacunha, a Brazilian immigrant and Barnstable resident, told Bolts. She moved to this country 18 years ago and gained citizenship seven years ago. “ The level of anxiety and tension is huge in our community.”

Among more than 3,000 sheriff’s offices in the country, only about 130 have this arrangement with ICE. Of this sliver of 287(g) participants, sheriffs are up for election this November in 39 counties—34 of which voted for former President Donald Trump in 2020.

Barnstable is one of the exceptions. It favored Joe Biden over Donald Trump by nearly 25 points. Once a Republican stronghold, it has voted for Democrats in every presidential election since 1992. Most local politicians, including every county commissioner, is a Democrat, though the outgoing sheriff is a Republican and the GOP has held the district attorney’s office for the last 51 years.

Immigrant rights advocate Mark Gabriele, a member of the community group Cape Cod Coalition for Safe Communities, says people in the county don’t particularly favor punishing non-citizens, but rather many in the resort communities that dot this part of southeastern Massachusetts simply aren’t aware of the program that lumps additional anxiety onto an immigrant community already on high alert.

“It never dawns on a lot of people that we have this active 287(g) thing, this certainly unfriendly atmosphere,” he said.

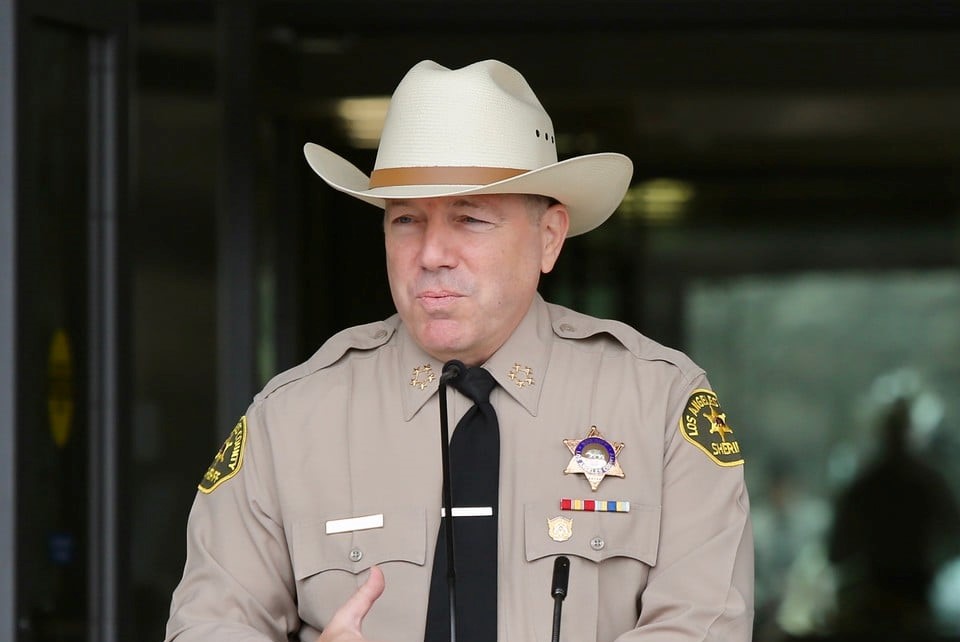

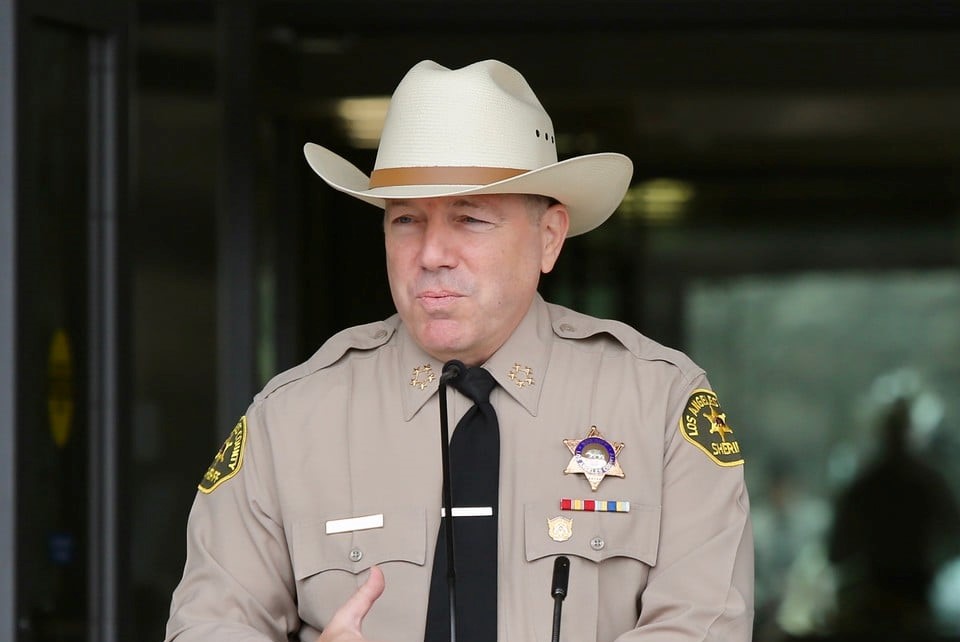

The sheriff who signed this agreement, Republican James Cummings, has for years published demographic information about the people his office refers to ICE each month—in total, more than 300 people since 2018. (A Syracuse University national database shows that ICE placed detainers on people held in the county jail during the partnership, though not all may have been deported.)

This could all change soon, though. Cummings is retiring after 23 years on the job, and in November voters are set to choose a replacement in a contest where cooperation with ICE has become a faultline. Republican lawmaker Tim Whelan wants to preserve the ICE partnership, and Democratic attorney Donna Buckley says she’d “rip up” the 287(g) agreement on her first day in office.

Buckley, who served as general counsel for Cummings for the last four years, says she only decided to run this spring because, she said, she lacked confidence in Whelan to reform an office she’s observed as failing to prepare incarcerated people for success after release. Her entry into the race gave voters an affirmative choice in a contest that otherwise would be unopposed.

“The sheriff’s office should not be doing ICE’s job,” Buckley said. “The sheriff’s office should be focusing on all of the people who come out (of jail) and make sure they do not commit more crimes, that they do not have more victims, that they don’t overdose and die, that they don’t put our police at risk.”

“[The 287(g) agreement] has nothing to do with correction, rehabilitation and treatment of people who are sent to the custody of the sheriff, and it needs to go,” Buckley added.

But it speaks to Gabriele’s point about the relative apathy on this issue that even Buckley emphasizes her position on immigration enforcement is not a defining part of her platform. She describes the 287(g) involvement as merely symptomatic of what she alleges to be a broader problem of mismanaged priorities in the office, as opposed to casting it as a matter of social or racial justice. She also says the issue does not come up much on the campaign trail.

“One thing I’ve definitely noticed,” said Sarang Sekhavat, political director at the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition, “is that immigration, for folks who support immigration and pro-immigrant policies, is a low priority. It’s not the kind of thing they’re usually calling their legislators about.”

Many in Massachusetts may also have no idea where a sheriff fits in on immigration enforcement. A recent survey by the firm Beacon Research showed most in the state don’t know the name of their sheriff and don’t understand well what the job entails.

Whelan, who didn’t respond to requests for an interview for this story, told The Provincetown Independent that 287(g) is “a tool by which we can keep Cape Codders safe.” Proponents of 287(g) often cast it as a crime-fighting measure, since it consists of researching people after they are brought into a jail—though nationwide data shows that 287(g) is typically used against people arrested for low-level offenses or traffic infractions. Cummings, who is currently being sued over the program by Lawyers for Civil Rights and Rights Behind Bars, also defends it.

“What we’re doing is working, and it’s not costing us a lot of money and all the things they’re saying about immigrants’ rights, it’s all B.S.,” Cummings told The Cape Cod Times.

The lawsuit argues it is, in fact, costing taxpayers money, and draws on the Cape Cod Times reporting that showed the sheriff’s office spending more on overtime pay even as the number of people jailed there fell in the pandemic. The suit notes that some sheriff employees who’d earned the most in overtime were also among the handful who’d been specifically trained and deputized under 287(g). One of them, Corrections Officer Kevin Fernandes, had a salary of $85,050 last year and made another $60,476 in overtime, the lawsuit states.

Critics like Gabriele also fault the program for perpetuating racial disparities within the legal system.

Barnstable County is about 92 percent white, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The Cape Cod Coalition for Safe Communities has compiled a running tally of Cummings’ published demographic information, showing that Black men comprise the plurality of those the sheriff has reported.

According to this data, out of the more than 320 people Cummings has listed over the years, at least 98 are from Jamaica—easily the largest share by country of origin. The largest group of immigrants on the island by far is Brazilians, but there are about half as many people from Brazil as from Jamaica in Cummings’s published statistics.

Said Buckley of Cummings’s policy to publish information about jailed immigrants, “It’s making them look like these bad scary people and not acknowledging the fact that they’re no different than anyone else” incarcerated in Barnstable County.

In Massachusetts, unlike in many other states, sheriffs are almost singularly empowered to run jails. They do not have regular patrol and arrest duties. In her interview with Bolts, Buckley pointed out that she would have no control over deciding which people end up in custody.

Still, the participation in 287(g) exacerbates a problem of disproportionately harsh policing and incarceration that affects Black men in Barnstable as well as in the state at large. A 2020 report by the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School documented large racial disparities in Massachusetts throughout the stages of the criminal legal process, fueling huge differences in the incarceration rate among white, Latinx, and Black residents.

“There are all these layers of where the problem could be originating,” Gabriele said. “It could be in (racial disparities in) accusations, in prosecution. You don’t get screened for the 287(g) until you’re actually on the premises of the jail, so the overrepresentation of Jamaicans could’ve originated earlier in this whole criminal prosecution process.”

Whether or not Buckley wins, there are signs that 287(g) may be on its last legs in Massachusetts. It exists now in just two areas: in Barnstable, and in an agreement between ICE and the state prison system.

County-level agreements have already been reversed in neighboring Plymouth County, where the sheriff voluntarily ended the program a year ago, and in Bristol County, where the Biden administration terminated the 287(g) contract after a scathing state investigation into a violent episode in 2020 in that county’s now-shuttered ICE detention center. The office of Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey found the Bristol County officers had committed civil rights violations and recommended the termination.

Healey, a Democrat, is running for governor this year and heavily favored to win. Her campaign did not respond to repeated requests for comment on whether she’d preserve the state prison system’s 287(g) agreement.

If she wins, she would succeed Republican Governor Charlie Baker, who this year vetoed a bill to grant driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants. The Democratic legislature overrode his veto, but opponents collected enough signatures to force a referendum in November on whether to repeal the new law.

Dacunha argued that the changes that this election may bring would make Barnstable County a safer home.

“People want to pay taxes, contribute to the communities, get their status, not be afraid to do that,” she said. “Somehow, they are here. So what are we going to do about it? Close our eyes and abuse them?”