New Jersey May Open Juries to Most People with Criminal Convictions

New Jersey has one of the nation's harshest jury exclusion laws. A bill championed by formerly incarcerated people seeks to walk that back and make juries more diverse as a result.

Alex Burness | January 29, 2024

Accused of armed robbery 20 years ago in Somerset County, New Jersey, Dameon Stackhouse had reason for hope when he headed to trial: the charges the state had filed against him suggested he’d used a weapon, and he knew he had not. If he could prove his innocence on that front, he could spare himself an extra decade in prison.

His confidence faded as jury selection began. Stackhouse, a Black man then in his late 20s, found no one who looked like him among the pool. There were no Black males and few people of color at all, and hardly anyone close to his age, he recalls.

“I was terrified,” Stackhouse, now 47, told Bolts. “I remember going through and trying to select individuals who I felt would at least hear my side of what happened, but then I was going to trial knowing that I could definitely be speaking on deaf ears.”

Stackhouse was convicted and later incarcerated for 12 years.

The jury arrangement in his case was hardly an unlucky break. By design, New Jersey jury pools are unrepresentative of the populace, in large part because of state law excluding people with past convictions from juries for life.

These exclusions massively bias the jury pool because New Jersey’s criminal legal system so disproportionately targets Black residents, from police stops to sentencing. The state permanently bars about 25 percent of Black adults from serving on a jury, according to estimates shared by the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice. By comparison, it bars 7 percent of all adult residents.

These are high rates even by national standards. Though every state excludes some people with criminal records from juries, New Jersey’s policy is unusually harsh: It bans people from jury service for life if they’ve been convicted of any “indictable offense”—a category which include felonies as well as some lower-level crimes that would be considered misdemeanors elsewhere. Only four other states are as restrictive as New Jersey: Maryland, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Texas.

A free man today, Stackhouse is now helping to champion a proposed reform meant to make New Jersey juries more representative of the communities in which they serve. Assembly Bill 834, filed earlier this month, would allow anyone to serve on a jury so long as they are not currently incarcerated for an indictable offense.

The bill calls for the continued exclusion of those who’ve been convicted of murder or aggravated sexual assault, but otherwise opens jury service up to everyone living on the outside—including those on parole or probation. Its passage into law would instantly make New Jersey’s jury exclusion law one of the country’s most permissive.

“New Jersey has an opportunity to be a leader in the nation, and a leader in one of the best ways: having our juries be robust and reflective,” Emily Schwartz, senior counsel for the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, told Bolts. “We have an incredibly diverse state of all life experiences. That can only make this process a stronger one.”

New Jersey lawmakers have been debating this question as far back as 1995, when the state adopted a law permitting jury service for anyone who’d completed a full sentence for an indictable offense—only to repeal it in 1996.

More recently, lawmakers have considered reforms to expand jury service eligibility every session since 2018. This year’s proposal seems to have real momentum, as a reform identical to AB 834 already cleared one chamber of the statehouse in early January, at the end of the last legislative session. AB 834 was filed the next day, at the onset of the current session, sponsored by Assembly members Verlina Reynolds-Jackson and Shanique Speight, both Black women.

“We’re getting close,” Stackhouse said. Schwartz added she believes this bill can pass by the summer.

New Jersey, like the rest of the country, owes much of its jury exclusion practice to explicitly racist post-Reconstruction campaigns to keep Black people out of jury boxes. Those efforts are still serving their purpose today; all across the country, Black and other Americans of color overall are disproportionately more likely to be arrested and incarcerated. This means they are less likely to serve on juries, either because of exclusion for past convictions or because of state policies that alienate marginalized communities from civic life.

Plus, defendants must contend with a criminal legal system in which trial judges and elected prosecutors are almost always white.

“We’re whitewashing a space that’s disproportionately affecting Black and brown communities,” Schwartz said, “which really calls into question: who is getting a jury of one’s peers?”

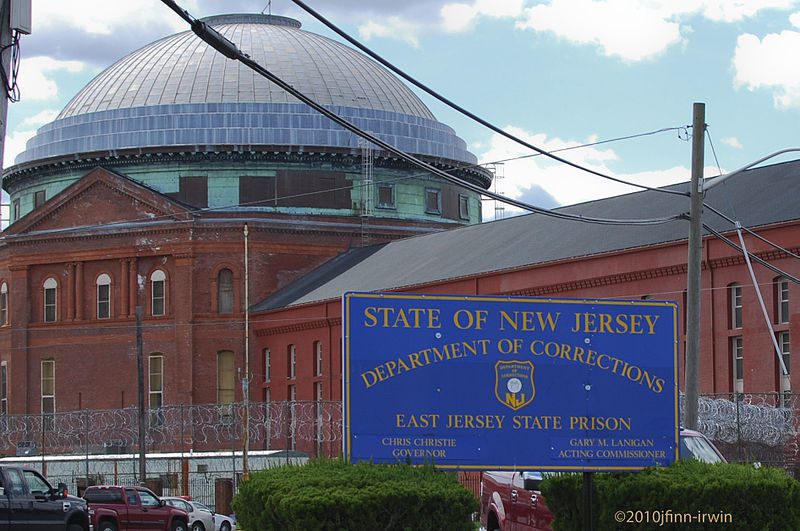

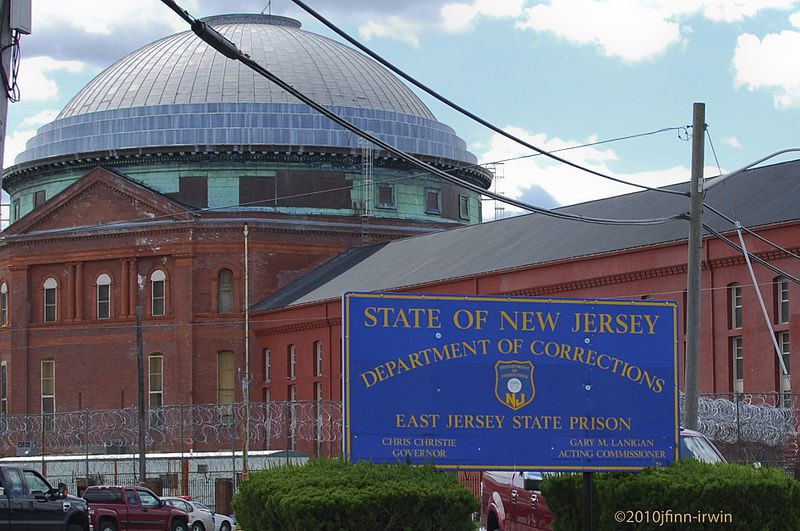

The upshot in New Jersey is a disparity between imprisonment rates for Black and white citizens greater than in any other state in the country. The Sentencing Project reported in 2021 that Black New Jerseyans were 12 times likelier than their white neighbors to be incarcerated—more than double the national average disparity.

In New Jersey and the U.S. overall, the vast majority of criminal cases never go to trial, resolving instead with plea deals. Among the reasons why, several formerly incarcerated New Jerseyans and criminal defense attorneys told Bolts, is the discouragement that comes from knowing one’s fate at trial may well be determined by a set of people who cannot relate to the defendant.

“The expected composition of the jury affects the way we advise people about whether to go to trial, in certain types of cases,” said Andy Elders, a Virginia-based public defender. “If our defense is going to be that the police are lying, or that there was police violence, or if our defense is that the accused fled from the police because he was afraid of them—those are experiences that are more likely to be racially coded, where, for example, Black people may have different experiences than white people.”

Research has shown that more diverse juries are less quick to convict, deliberating longer and more thoughtfully. One study conducted in the Houston area concluded that proportionate representation on juries could reduce median sentence terms by 50 percent.

“More perspectives on juries means more understanding,” Schwartz argued. “In a room where you have 100 people and they all hear the same story, what each person takes from that story can shift a little bit, so doesn’t it give more credibility to the process to have more perspectives?”

The jury selection process, known as voir dire, is already designed to dismiss those who demonstrate biases that could cloud their judgment. At the heart of the argument for New Jersey’s reform is the basic premise that everyone has a unique worldview that precludes total impartiality, and that it is thus unfair to exclude one class of people entirely.

“Ultimately, the prosecutor and the attorney have to agree on who sits on the jury. There’s a process in place to weed them out, so why wouldn’t we be included in that?” Frank Gilmore, who was incarcerated for seven years in New Jersey, told Bolts.

Gilmore is now a city council member in Jersey City. It’s one of the most racially diverse cities in the country, with roughly equal numbers of white, Asian, Black, and Latinx residents—but Gilmore recalls that the jury in his trial was mostly white. The conviction resulting from that trial is still keeping him from serving on juries today, which he finds especially, bitterly ironic.

“I’m a legislator; I create legislation, I write laws. Who better to judge if someone broke the law than a person that created it?” he said. “It doesn’t make sense, and it’s not consistent with this idea that we give people second chances.”

Gilmore and others backing the New Jersey bill say they’re concerned that it carves out those convicted of murder and aggravated sexual assault. Schwartz called this a “kneejerk reaction to what [lawmakers] think of more upsetting crimes,” and said this selective exclusion “also ignores the reality that we all have our biases.”

Rev. Dr. Russell Owen, who was released from prison in 2021 after being incarcerated for 32 years on a murder conviction, said that the exclusions in the bill also serve to keep people like him in a permanent underclass. “They’re telling me there’s a limit to my integrity, a limit to my goodness, a limit to my rehabilitation,” Owen, now a community organizer with Faith in New Jersey, told Bolts. “I am not a carve-out. I am more than that, but what they’re saying is that I’m still not a real citizen.”

But those proposed carve-outs were the product of an amendment to last session’s version of the bill that passed late last year by a Democratic-controlled Assembly committee and later by the full Assembly. Advocates aren’t happy with the change, Schwartz said, but they feel it makes the bill much more likely to pass.

Ann Roan, a longtime public defender who has lectured around the country on voir dire, warns that even if New Jersey’s bill does become law, it may not make juries much more racially representative. Roan has seen up close how a law that appears inclusive on paper may not play out in practice: she’s from Colorado, which has one of the country’s most permissive laws on jury exclusion, and she said racial bias still very much persists there in jury trials.

Though the U.S. Supreme Court has held that one cannot be dismissed from a jury pool simply on the basis of race, Roan said plenty of proxy options remain. Those hailing from communities that experience heaviest policing and incarceration are often most skeptical of law enforcement, Roan has found. In the voir dire process, she said, many prosecutors find such skepticism to be disqualifying.

“Your lived experiences and your honesty about your lived experiences only work if those lived experiences are congruent with support for law enforcement. Otherwise you’re deemed not fit to serve,” Roan said.

“I tend to believe that if this bill in New Jersey passes, you will not see skyrocketing numbers of prior convicted felons being part of juries, because prosecutors are not going to let that happen.”

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.