“This Election Is So Quiet”: Inside the Scramble to Mobilize Milwaukee in a High-Stakes Judge Race

Tuesday’s supreme court showdown will shape Wisconsin’s future and is breaking spending records—but it’s all coming down to an off-year, springtime, low-turnout election.

Katjusa Cisar | March 30, 2023

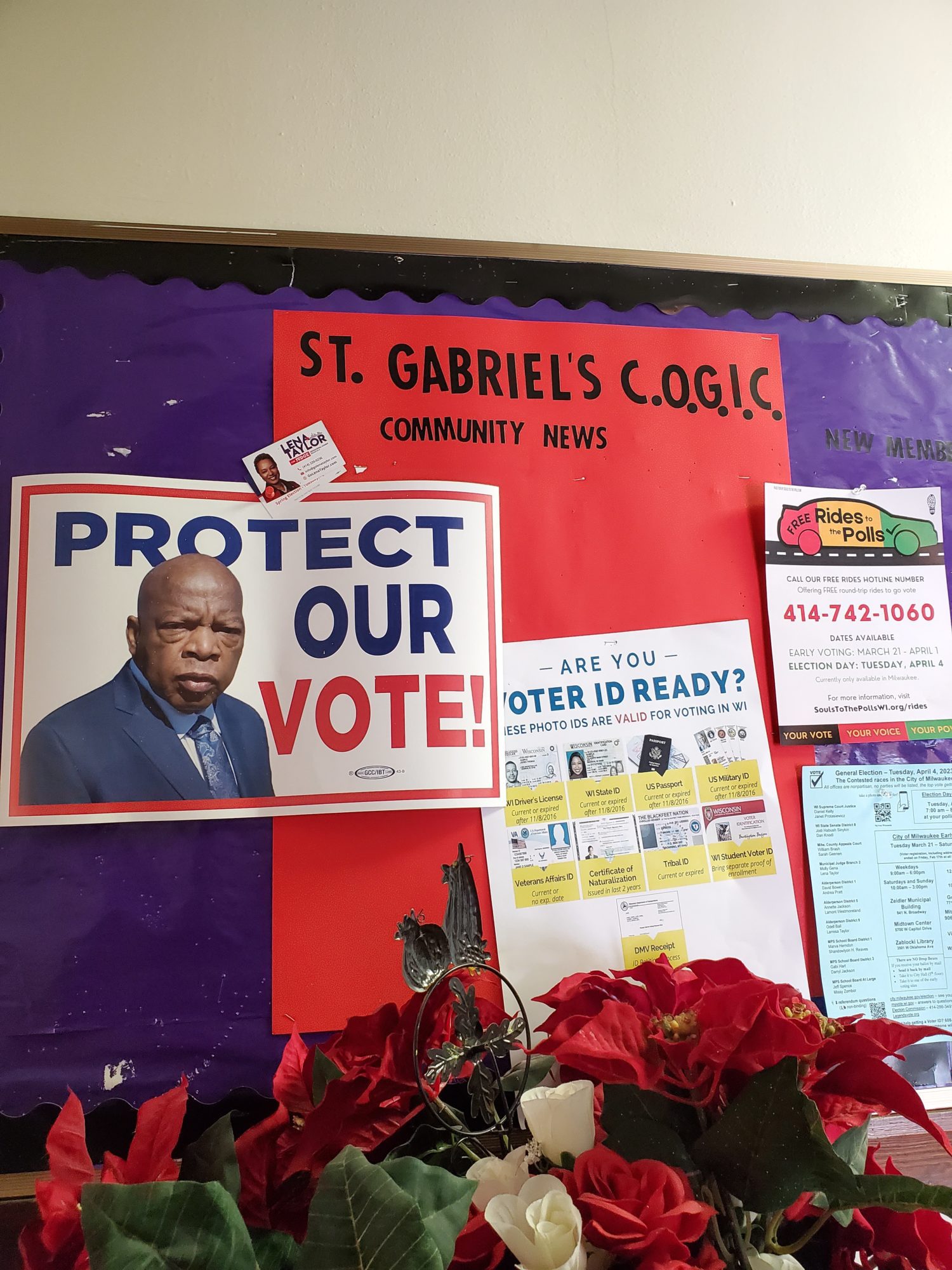

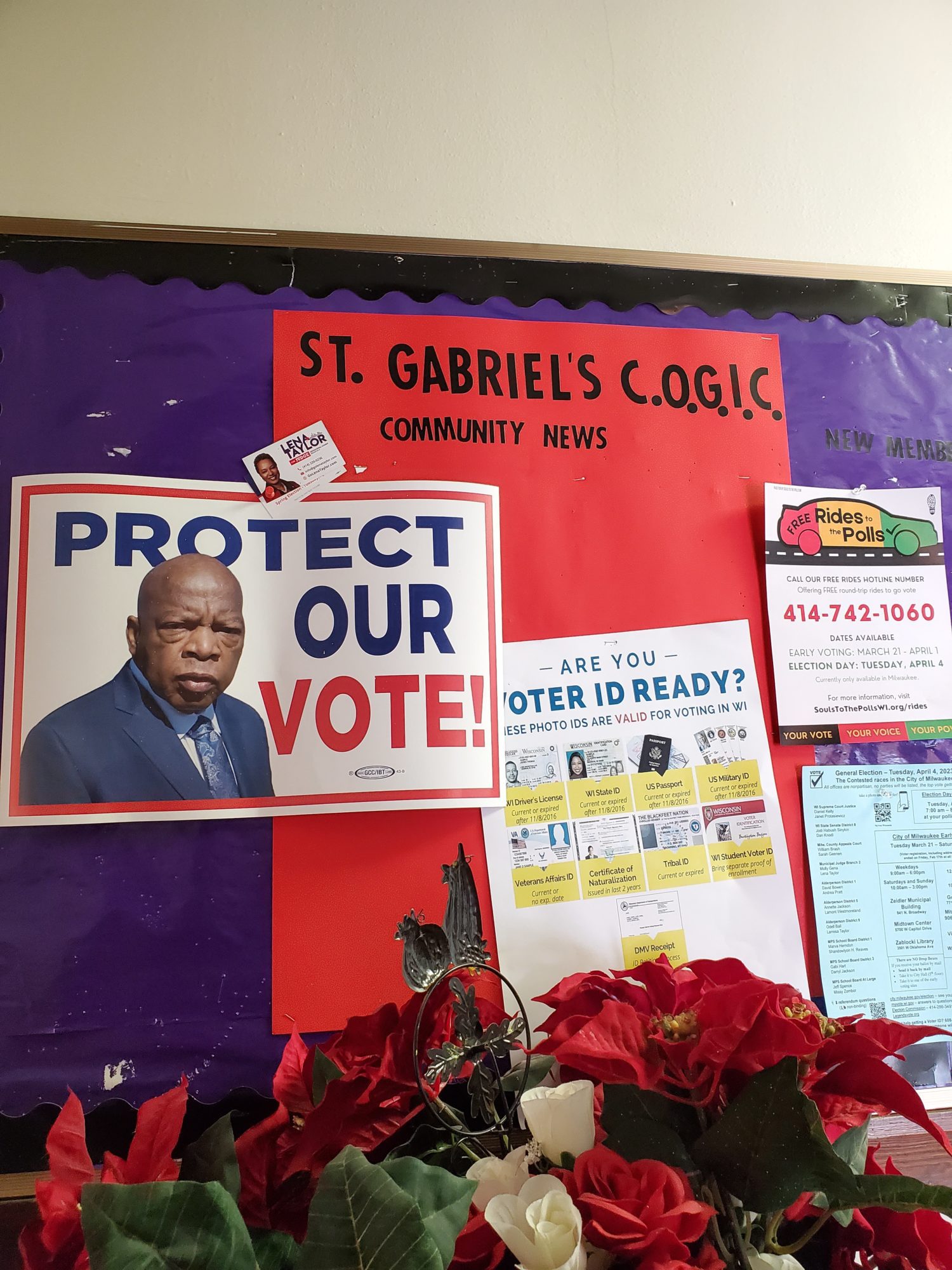

On a Saturday morning this month, several dozen people turned out to the St. Gabriel Church of God in Christ, on the majority-Black north side of Milwaukee, for a town hall about Wisconsin’s April 4 supreme court race. The live-streamed event was organized by The Union, a national organization set up by The Lincoln Project, and by local groups that promote higher voter turnout, such as Souls to the Polls and Milwaukee Turners.

In the church vestibule, someone had put out free “Justice 4 Wisconsin” spice packets from the outspokenly progressive spice company Penzeys, which is headquartered in the Milwaukee area and has trademarked the phrase “Season liberally.” “Wisconsin’s Republicans lie and cheat, and when we stay silent they win,” says the messaging on the packet. “Speak out for Justice, our environment, a fair playing field for all, and the importance of voting April 4.”

The event itself was nonpartisan and the candidates’ names were barely mentioned. Instead, the panelists discussed how they grapple with getting out the vote in underserved Milwaukee communities that are struggling with gun violence, underfunded schools, and food deserts.

They lamented the challenges of organizing in Milwaukee given some state conservatives’ undisguised hostility toward the voters of color who make up the majority of the city’s population. Most recently, a GOP member of the Wisconsin Elections Commission bragged to other Republicans in a January email about a successful voter-suppression campaign “in the overwhelming Black and Hispanic areas” of Milwaukee; the commissioner, Bob Spindell, refused calls to step down and has not been disciplined.

“There’s so many needs pressing our community today. When we talk about disparities in this country, Milwaukee leads the nation,” said panelist Sharlen Moore, who co-founded the local youth leadership program Urban Underground in 2000. To energize voters, “we got to get back to the block” and build community with neighbors.

Another panelist, 20-year-old activist Deisy España, shared a message that she said resonates with her peers, many of whom—like España—have immigrant parents who cannot vote. “I tell them they’re voting for their parents,” she said.

After the town hall, attendee Deborah Thompson told Bolts that in her neighborhood of Heritage Heights, a small middle-class, majority-Black community about six miles northwest of the church, she is talking with her family, friends and Bible study group about voting on April 4.

“Democracy is a big concern of mine because I do see it as under threat,” said Thompson, who is 75. To encourage people to vote, she first brings up the erosion of voting rights and the loss of ballot drop boxes, which the state supreme court disallowed last year in a 4-3 ruling.

“If I feel safe enough, then I’ll bring up women’s rights,” she added.

Tuesday’s election will settle if conservatives keep a majority on Wisconsin’s supreme court or if it flips to the left, and all of those issues hang in the balance. Amid an outpouring of national attention and spending, the urgent questions the race will decide have dominated the campaign and its coverage. Will the state’s abortion ban from 1849 survive a legal challenge, will Wisconsin end up with fairer electoral maps for the rest of the decade, will voters regain access to drop boxes? For people who are volunteering their time on this race, these stakes are as enormous as they are self-evident.

But they also face a difficult reality. This momentous showdown is taking place in an off-year, springtime, low-turnout election, far from the energy that greets a presidential race.

Mobilizing people to come out in elections that aren’t synced with national cycles is always a challenge, and there’ve been efforts across the country to move their time. “Historically these spring elections have extremely low turnouts. This election is going to be all about who gets the people out to vote,” Christine Sinicki, a Democratic Assembly member who represents the southernmost parts of Milwaukee and some adjacent suburbs along Lake Michigan, told Bolts.

Roughly 960,000 people statewide cast ballots in the first round in February that decided which two judicial candidates would move on to next week’s general election. That’s a huge drop from November 2020, when nearly 3.3 million Wisconsinites voted for president. It’s an especially pressing headache for liberals: The drop-off is far more prevalent in Milwaukee, an engine of Democratic politics, than in the outer ring of conservative suburbs that power Wisconsin’s GOP candidates.

As a share of all registered voters, turnout in February was 26 percent in Milwaukee County and 33 percent in the WOW counties. Within just the city of Milwaukee, it reached only 22 percent.

In Wisconsin’s nail-biters, these shifts can make all the difference. And now, control of the state’s supreme court hinges in part on whether organizers in Milwaukee persuade and help enough city residents to vote.

Restrictions that have been blessed by that same court, like the ban on drop boxes, have not helped. A Republican law adopted in 2018 also cut back early voting in Milwaukee from nearly six weeks to two weeks before an election. That makes it harder for working families in Milwaukee to find time to vote, Sinicki said. “There’s a lot of people out there working two jobs who just can’t get there on Election Day.”

Even within the city of Milwaukee, turnout is not spread evenly. According to an analysis by Marquette University researcher John Johnson, Milwaukee’s overall voter turnout in recent years has declined, with the biggest losses in low-income and predominantly Black and Latinx areas. That pattern held in the first round in February: Turnout varied wildly, from roughly 5 percent of registered voters in some wards to roughly ten times that rate in more affluent neighborhoods.

In the ward that contains St. Gabriel Church of God in Christ, turnout reached only 12 percent in February—down very precipitously from where it stood in the November midterms, 51 percent.

LaToya White, another panelist in the town hall, pointed to the disparities felt by residents on the north side of Milwaukee, especially younger people. “Being an organizer, you’re in the community every day, and you see our youth,” she said. “They feel like they’re left out.”

White works at Wisconsin Voices, a community organization that promotes civic participation; she saw “amazing” engagement here last fall but this has not carried into the judicial race. “This election is so quiet,” she said. “A supreme court race to them, they don’t see how important this is and don’t know that this election here is one of the most important out of the next ten years.”

In a race where so much is at stake, organizers and party representatives aren’t sticking to one issue to energize voters.

“A lot of people until recently I don’t think understood the importance of the supreme court and how important it was to our day-to-day lives and our rights,” Sinicki said. “People are finally waking up. I always said we have to hit rock bottom before people realize what’s going on here, and I think we’re there. If they can strip away our rights to control our own healthcare, what’s next?”

A lawsuit against the state’s abortion ban is working its way through state courts, and Janet Protasiewicz, the liberal candidate in the race, has campaigned on her personal support for abortion rights. Last week, in her only public debate with her conservative opponent Daniel Kelly, Protasiewicz said, “If my opponent is elected, I can tell you with 100 percent certainty, that 1849 abortion ban will stay on the books.”

For reproductive rights advocates, anger over the ban is tied in with concerns about democracy in Wisconsin. There is no plausible path for Democrats to overturn it legislatively because Republicans have maintained ironclad control over Wisconsin’s legislature thanks to the heavily gerrymandered electoral maps they have drawn. The maps are widely considered some of the most skewed in the country. Sam Munger, an election consultant and panelist at the town hall, said the maps have “rendered voting largely irrelevant.”

But the supreme court election is a statewide race, so it offers Wisconsinites the opportunity to vote outside the confines of those gerrymanders. Protasiewicz has called the state maps “rigged” and many Democrats hope that a liberal court could strike them down.

Protasiewicz’s supporters talk up the election’s implications for the future of voting rights. The Democratic Party of Wisconsin held a “Voting Rights Panel” in mid-March on Milwaukee’s north side to address issues of gerrymandering and voter suppression, in the presence of prominent Democrats like former Lieutenant Governor Mandela Barnes, who lost the U.S. Senate race last fall.

Conservatives are mobilizing around the same issues. Wisconsin’s leading anti-abortion groups have rallied around Kelly.

Scott Presler, a young, pro-Trump conservative from Virginia and founder of the Super PAC Early Vote Action, has spent the last couple of weeks in Wisconsin, door-knocking and making appearances to get out the Republican vote for Kelly, with the long-term goal of advancing what he calls “election integrity” in swing states to ensure a win for Trump in 2024. On a March 16 episode of Steve Bannon’s War Room show, Presler called the April 4 election “one of the most consequential elections in Wisconsin history” because of the state supreme court’s control over voter access issues like ID and proof-of-residency requirements.

“If the liberals are able to win on April 4, we will have unmanned drop boxes in Milwaukee and Madison going into the 2024 election,” he warned. The morning after the first day of early voting last week, Presler took to Twitter to celebrate strong turnout numbers in conservative Waukesha County and to call on people to vote in a string of counties that did not include Madison and Milwaukee.

Other Republicans are also treating Milwaukee, where Protasiewicz serves as a local judge, as a foil for the rest of the state. That’s a frequent campaign tactic for the GOP in Wisconsin. Some are already floating impeaching her over her work as a Milwaukee judge if she wins. (On the same day as the supreme court race, a special election for a state Senate seat will decide if the GOP has the Senate supermajority it would need to remove a state official on a party-line vote.)

The judicial race is ostensibly nonpartisan but Democratic groups are backing Protasiewicz and Republican groups are supporting Kelly, a lawyer who used to sit on the state supreme court and has a long history in conservative politics.

Money has poured into the race, reflecting national interest but also lax campaign finance rules that allow for massive expenditures. Total spending in the supreme court race is already near $45 million with a week to go, according to WisPolitics, which triples the national record for a judicial election.

That includes at least $15 million in independent spending since Jan. 1, according to the Wisconsin Ethics Commission. Groups supporting Protasiewicz have a slight edge in spending as of publication, but far more of the money on the liberal side has gone directly into the candidate’s campaign coffers. Billionaires George Soros and J.B. Pritzker, the Illinois governor, are among the largest liberal donors, while conservatives include megadonors Richard and Elizabeth Uihlein and Federalist Society co-chairman Leonard Leo. People and groups with ties to the efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election have also donated millions to help Kelly.

But as the panelists of the St. Gabriel Church town hall attested, that noise isn’t heard equally in all parts of the state.

After the March 18 town hall, a few groups of volunteers left to canvass nearby. They handed out nonpartisan fliers that listed general election and early voting information.

Milwaukee resident Jodi Delfosse, 55, took a stack of fliers and walked up and down a nearby block knocking on doors. It was a finger-numbing 16 degrees and the weather switched disorientingly between blizzard-like snow and clear sunshine every few minutes. She was met mostly by Ring security systems, with residents answering the door through their intercom, and a few face-to-face interactions. In a friendly voice, one resident told her through a closed door to leave the flier outside because “I’m not dressed.”

These obstacles to reaching voters door-to-door was one reason Linea Sundstrom started Supermarket Legends, a nonpartisan Milwaukee voter advocacy group that is run exclusively by volunteers, mostly retirees. They pass out informational literature and register voters outside local supermarkets and food pantries, at bus stops, on college campuses and on public sidewalks or outside any business that gives them permission.

“Everybody has to eat, and what we’re trying to do is go where people are instead of expecting them to come to us,” she told Bolts. The group’s flier for the supreme court race does not advocate for a candidate but identifies issues with a series of questions, such as “Is the 1849 abortion ban right for Wisconsin today?” and “What regulations are right for tap water?”

Supermarket Legends focuses on low-turnout areas and wherever “people don’t have a lot of resources,” Sundstrom said. They pay attention to where other groups are working and “try to fill in the gaps.” Right now, she said, the biggest gap is on the near-south side, a predominantly Latinx area where voter turnout outside of major elections is typically very low.

Sundstrom described her group’s work in a ward where only 29 people voted in February, which is only 6 percent of registered voters. “One person standing in front of El Rey Supermarket on the south side can talk to 60, 70 people an hour, face to face,” Sundstrom said.

Sylvia Ortiz-Velez is a Democratic lawmaker who represents the Wisconsin Assembly district with the highest share of Latinx residents in Wisconsin. Two weeks out from the runoff, she was canvassing her constituents in Milwaukee’s Polonia neighborhood, which is located about three miles south of the El Rey supermarket. Voter turnout is reliably higher in this neighborhood—26 percent in the primary—as is household income.

Going door to door is a way to reach the registered voters who regularly vote because they are the “lower-hanging fruit” of any get-out-the-vote campaign, she said. Plus “you learn a lot about what’s landing.”

At one house, the barrel-chested 64-year-old who opened his door to Ortiz-Velez already had his mind made up about the two candidates. “Get rid of ’em both. They’re wishy-washy. We need law and order,” he told her. He was wearing a National Latino Peace Officers Association T-shirt. He said Protasiewicz is too soft on crime, echoing GOP attacks. He called Kelly, who was paid by state Republicans to advise them in a covert scheme to overturn the 2020 election, “a crook.”

Then he added: “The one thing I like about (Protasiewicz) is giving women their rights.”

This comment surprised Ortiz-Velez. “In my district, abortion might come up, but it might not come up. It’s not something I would lead with,” she told Bolts. “Most of the people in our community make maybe $35,000 per year and work very hard for their families and they’ve always had to do a lot with less.” If she has time, she said she’ll “absolutely talk” with voters about gerrymandering, rigged district maps and voter access.

Here in Polonia, Ortiz-Velez made sure to mention that Protasiewicz is homegrown—she grew up on the south side, her parents are buried in a nearby cemetery and she attends a Catholic church about eight blocks away.

As she walked, she consulted a canvassing app on her phone called MiniVAN. It tells her the name, age and voting history of registered voters on the block.

“Back in the day we put this all on index cards,” she said.

Ortiz-Velez has been canvassing in the district for over 20 years. Some things have not changed. “My father was an evangelist and he always told me, ‘Smile, smile, smile,’” she said outside one house while waiting for an answer at the door.