Elections Could Expand Voting Rights This Fall. They Will Take Place in an “Intolerable Condition.”

The November elections in Mississippi, Kentucky and Virginia could alter the politics of rights restoration and potentially expand the electorate.

Daniel Nichanian | September 26, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Hundreds of thousands of citizens are barred from voting in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Virginia’s elections this November. And whether they get to participate in future elections will be perversely decided by those who are already allowed to vote.

The electoral process “implicates every single thing about my current state, so to deny people the right to vote perpetuates an intolerable condition on human beings,” Shelton McElroy, a member of the grassroots group Kentuckians for the Commonwealth (KFTC) who is disenfranchised himself, said in reference to Kentucky’s exceptionally harsh criminal disenfranchisement laws. People who are barred from voting are organizing around the country to expand voting rights.

Kentucky disenfranchises more than 300,000 people for life because of a felony conviction, according to a study by the Sentencing Project. That number is more than three times the margin by which Governor Matt Bevin won the state’s last governor’s race, in 2015.

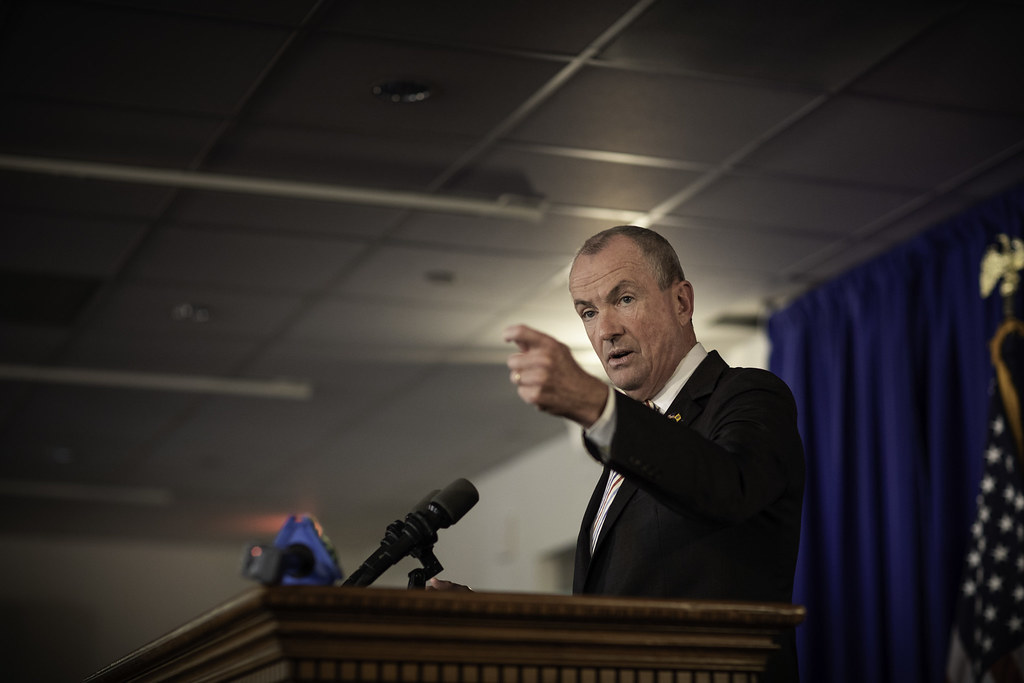

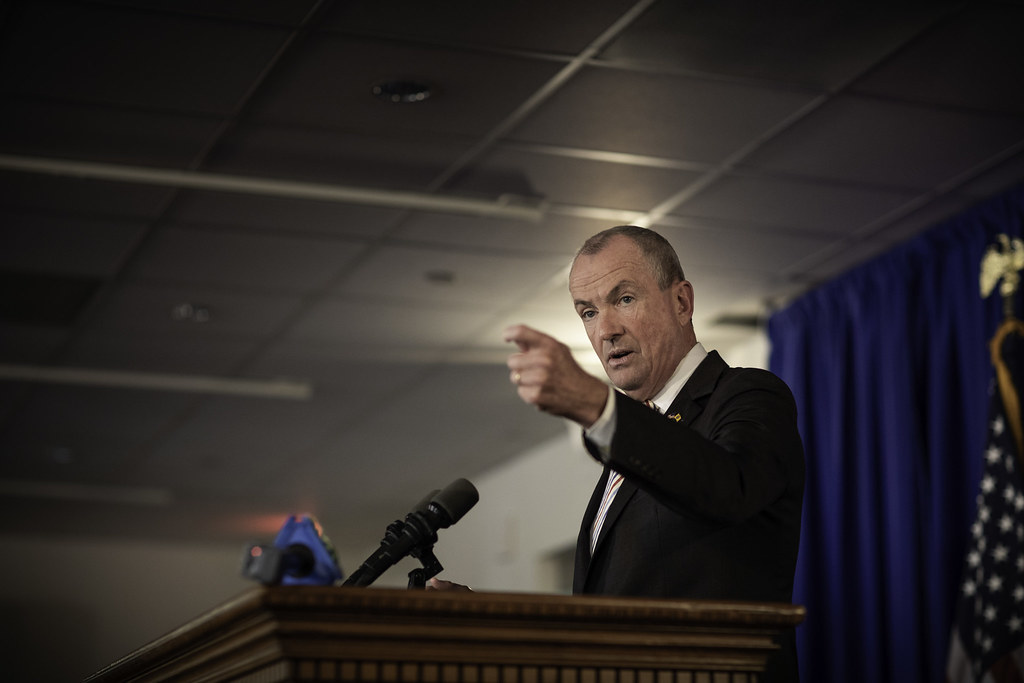

Andy Beshear, Kentucky’s Democratic attorney general, is running for governor this year on a platform of restoring the voting rights of tens of thousands of Kentuckians through his executive authority. He faces Bevin, the Republican incumbent, in the Nov. 5 election.

Here, as elsewhere, the system disproportionately affects people of color. The state disenfranchised 26 percent of all Black adults as of 2016, compared to 8 percent of the rest of the population.

“What kind of state is Kentucky, truly?” Tayna Fogle, an organizer with KFTC, told the Political Report last year. “What kind of democracy, if you take away folks, Black and brown folks?” McElroy, who is also an advocate with the Bail Project, a national advocacy organization, mirrored Fogle’s assessment this week. “It is a state that has perpetuated via policy and practice horrendous hardships and disparities on Black communities,” he said. “Denial of voting is just commonplace through Kentucky.”

Mississippi and Virginia are also having state and local elections that could alter the politics of rights restoration. In Virginia, they may usher in new legislative leadership that supports constitutional reform to expand the electorate.

Using executive authority

All three states have exceptionally harsh disenfranchisement laws. Kentucky and Virginia laws provide for a lifetime voting ban on anyone convicted of a felony; Mississippi imposes a lifetime ban for a long list of offenses, which range from perjury and theft to murder.

Although Virginia law is as harsh as Kentucky’s, in practice voting rights have been considerably more expansive there since 2016.

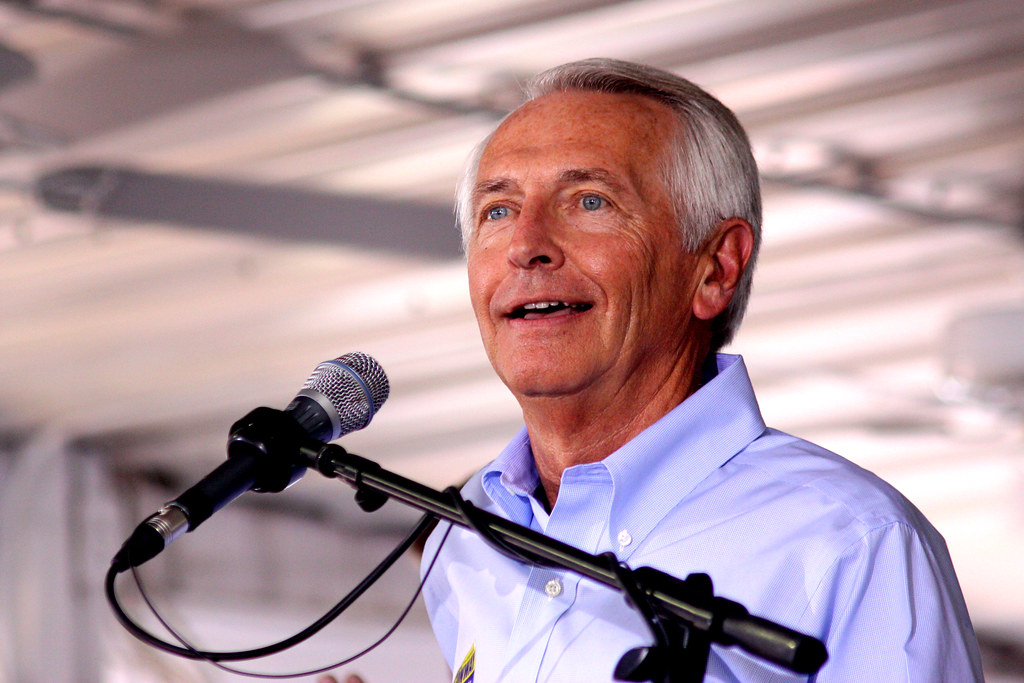

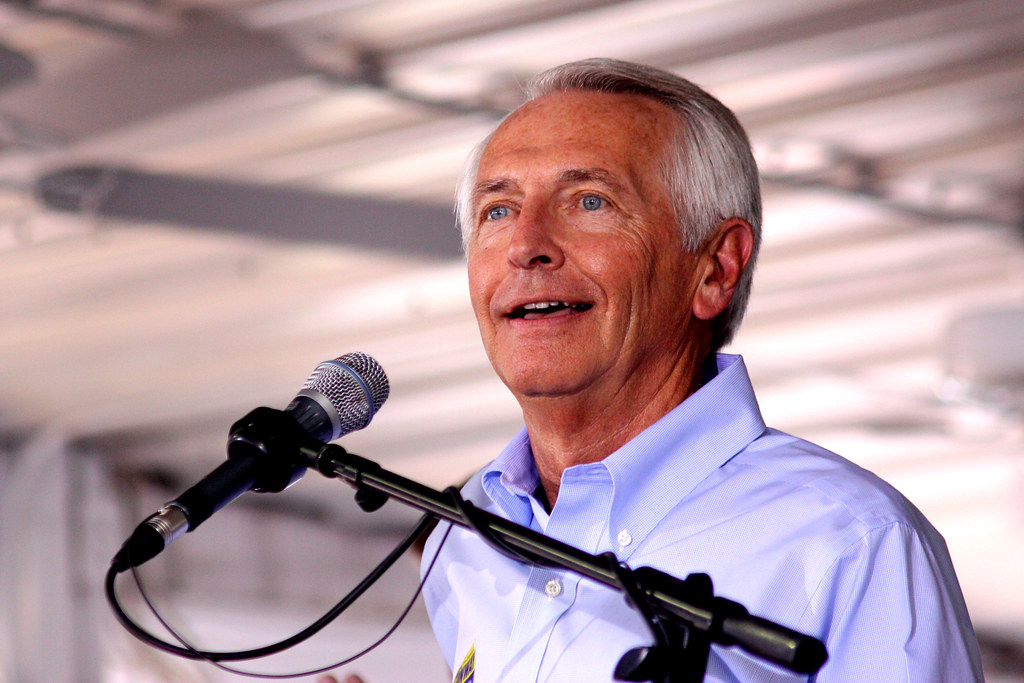

That year, then Governor Terry McAuliffe used his executive power to restore the voting rights of Virginians who had completed their sentence. He enfranchised approximately 173,000 people by signing an individual order for each of them. His initial attempt to issue one collective order was blocked by state Republicans through a lawsuit joined by a bipartisan group of prosecutors.

Both Democratic prosecutors who joined that lawsuit and then ran for reelection this year lost in the June primaries.

McAuliffe now holds up this initiative as a model for other states with lifetime voting bans.

Rights restoration “is so fundamental to our democracy, to that individual feeling of self-importance like he belongs or she belongs in the community,” he told the Political Report in an interview this week. “If you don’t have it, it’s going to cause you problems down the road.” McAuliffe also said that the disparities in the “racist criminal justice system” were a major factor in his own decision to take executive action in 2016. “If you were a person of color, you were going to get a disproportionately longer sentence,” he said. “To me, that is blatant racism, and until we fix our criminal justice system racism will exist.”

“I hope that other governors use what I did as an example of what they need to do in their state,” he added.

Kentucky is the likeliest to meet this call. Beshear says in his gubernatorial platform that, if he is elected, he will “sign an executive order that automatically restores voting rights for Kentuckians who completed their sentences after being convicted of a nonviolent felony.”

Such an order would be similar to the one issued in 2015 by Steve Beshear, who was then the governor and who is the father of Andy Beshear, the current Democratic nominee.

Steve Beshear released his executive order a mere weeks before he left office, even though he had been there for eight years. Bevin, his successor, promptly rescinded it, acting before its intended audience could take advantage to once more strip them of the right to vote. An estimated 140,000 Kentuckians qualified under the short-lived 2015 executive order.

The plan proposed by Andy Beshear, the 2019 candidate, is likely to have a similarly large impact. That number alone represents about 4 percent of the state’s voting-age population.

“There has been a lot of movement, some in a bipartisan fashion, to address Kentucky’s worst-in-the-country felon disenfranchisement law, so having a governor in office who is also committed to the reform would be positive for our democracy,” said Joshua Douglass, a professor of law at the University of Kentucky and the author of Vote for US, a book on the movement to expand voting rights. “The right to vote is the most fundamental, important right in our democracy. Enfranchising more people can only be seen as a positive step forward on this front.”

Beshear’s proposal would only apply to felonies classified as nonviolent, as did the 2015 executive order.

This restriction, which uses an overdrawn distinction between violent and nonviolent offenses, would leave out many Kentuckians who have completed their sentence, let alone others. These individuals would remain dependent on the current process to obtain an individual pardon—a burdensome and rare commodity.

Corey Shapiro, the legal director of the ACLU of Kentucky, said that, while Beshear’s plan would be a “positive first step,” it is incomplete. The ACLU “would like to see a much broader expansion,” he added, including a constitutional amendment that abolishes disenfranchisement.

But a spokesperson for Beshear’s campaign told the Political Report that the attorney general favors this carve-out because he wants to “put victims and survivors of violent crime … first.”

This policy would be more restrictive than Amendment 4, the rights restoration measure adopted by 65 percent of Floridians last year, and which contained narrower exceptions. It would also be more restrictive than McAuliffe’s policy, which made no distinction between categories of offenses. “The judge and the jury determines what a sentence should be,” McAuliffe told the Political Report in explaining his thinking. “Once someone has completed what the judge and jury decided the sentence or penalty should be, that should be the determinant.”

McElroy, of KFTC, warns against dividing people based on who is judged to be more deserving. “The idea that you can differentiate between the allegations, the convictions and the charges in a way that creates fairness is moot,” he said. “You can’t create fairness and agitate to democracy when it comes to voting, which is a God-given right, nothing that a man should be able to take from everybody, not even if a person is incarcerated—let alone when someone is released.”

McElroy also notes that partial reforms would disproportionately leave behind “Black, brown, and poor people.” Racial disparities increase at every stage of Kentucky’s criminal legal system, according to data published by the state’s Department of Public Advocacy. McElroy points to cash bail as one factor that compounds inequalities; people unable to afford it are likelier to plead guilty, and having a record can trigger further encounters with the criminal legal system.

In search of a “permanent fix”

Executive action, regardless of its scope, is a fragile remedy. Kentucky’s 2015 initiative didn’t last long, and Virginia law has not been changed since McAuliffe’s executive orders. Rights restoration there still hinges on the good will of whoever occupies the governor’s mansion.

“There needs to be a legislative fix, or some sort of permanent solution,” said Caren Short, a senior staff attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center, an advocacy group that works in Mississippi. Short was addressing the prospect of reform in that state. “We certainly wouldn’t want to discourage any current or future governor of Mississippi from using his or her executive pardon power to restore anyone’s voting rights or civil rights,” she said, “but it’s not a permanent fix.”

The campaign of Jim Hood, the Mississippi attorney general and the Democratic nominee for governor this fall, told the Political Report that Hood believes people convicted of nonviolent offenses should have their voting rights restored upon completion of their sentence. The campaign did not address whether he would use his executive authority to facilitate this, or ask the legislature to act first. The campaign of Lieutenant Governor Tate Reeves, the Republican nominee, did not reply to a request for comment about his views.

Lawmakers in both Kentucky and Mississippi filed bills on the issue this year, but these failed.

Legislative movement is likelier in Virginia, depending on the results of November’s legislative races. Democrats are trying to seize control of the state government for the first time since 1993 by flipping both chambers of the legislature. That could broaden the range of viable reform, given Virginia Republicans’ opposition to expanding rights restoration.

McAuliffe is asking the legislature to enshrine his initiative into law. “The governor should not be involved, it should be automatic,” he said. “We need to codify this.”

Narrowing what counts as a felony would also reduce the number of people disenfranchised in the first place. Virginia raised the threshold of felony-level theft from $200 to $500 in 2018, but that remains low by national standards.“You steal an iPhone, you become a felon, and you lose the right to vote for the rest of your life,” McAuliffe said. “That is so unfair, it is morally wrong.”

The legislature could also go further than the scope of McAuliffe’s 2016 policy. This year alone, three states restored the voting rights of people still serving a sentence. One of them is Louisiana, where a law adopted by a GOP legislature and signed by a Democratic governor has newly enfranchised many people who are on parole and on probation.

Virginia already has the roots of an infrastructure to end disenfranchisement altogether.

Two state lawmakers, both Democrats, have filed two measures, which are championed by the ACLU of Virginia, to restore the voting rights of all adult citizens, including those who are incarcerated. A GOP-run committee killed them on a party-line procedural vote in January.

Illustrating the turning tide on this issue, multiple candidates running for prosecutor this year told the Political Report that they questioned why anyone would ever be stripped of their right to vote due to a criminal conviction. “These disenfranchisement laws were about making sure that black people would not be able to vote, and I think that we need to pull ourselves away from that history,” said Parisa Dehghani-Tafti, Arlington County’s presumptive next prosecutor. “We should never forget that these laws are the vestiges of Jim Crow.”

McElroy also called on Kentucky to keep that legacy in mind, and stop treating the franchise as something one could lose. “We should be all equals,” he said, “and whether incarcerated, whether free, whether Black, whether white, whether straight, whether gay, whether lesbian, every single citizen in the state of Kentucky should have the right to vote. There should be no schism with that.”