A Double Blow to Disenfranchisement

Colorado and Nevada will now restore voting rights upon release from incarceration, amid nationwide efforts against disenfranchisement.

Daniel Nichanian | May 31, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Colorado and Nevada will now restore people’s voting rights upon their release from incarceration, amid nationwide efforts against disenfranchisement.

Colorado and Nevada adopted new laws this week that will restore people’s voting rights as soon as they are released from incarceration, as opposed to doing so at later stages of the legal system (if ever).

These reforms deal a double blow to a system that excludes and marginalizes millions of U.S. citizens, disproportionately African American, across the country. They are the latest successes in a nationwide movement to confront felony disenfranchisement. The movement has upended the voting rights debate and opened space for bolder reforms than we have come to expect, whether ones like Colorado and Nevada’s or ones that go further by targeting disenfranchisement altogether.

Prior to this week, just one state had passed a law to enfranchise people upon their release over the last decade (Maryland in 2016). Colorado and Nevada did this within a day of one another.

Other legislatures ignored the issue or killed reform proposals this year, however. The fate of voting rights is now squarely on the national agenda, but politicians often do not follow through in the legislative spaces where there are opportunities to move the needle.

Tens of thousands of people will be able to exercise their right to vote

Nevada had some of the country’s harshest statutes as one of 12 states where some people could not vote even after completing their sentence.

The new law enfranchises people who have completed their sentence (as Florida’s Amendment 4 mostly did). But it also goes further by enfranchising people who are on probation and on parole.

Approximately 75,000 Nevadans were disenfranchised in 2016 for reasons that will no longer exist in 2020, according to a Sentencing Project report; that’s more than 3 percent of the voting-age population. Twenty-three percent were Black, even though African Americans represent only 8 percent of the state’s voting-age population.

Colorado’s new law reaches the same point through a smaller jump since its statutes were less restrictive to start with. The state disenfranchised people who are in prison and on parole; this reform ends the latter. There were approximately 9,000 Coloradans disenfranchised while on parole in 2016. Of those, 17 percent were African American, compared to 4 percent of the state’s voting-age population.

Both states are governed by Democrats. Every single Democratic lawmaker supported these two bills. (That’s 100 in total; the two governors are Democrats too.) But the reforms drew some Republican support as well; 13 of 61 GOP lawmakers backed expanding voting rights.

The changing landscape

Colorado and Nevada make it 16 states that will restore people’s voting rights after incarceration. Florida and Louisiana also implemented reforms that increased voting eligibility—these reforms that are not as expansive—earlier in 2019.

Neither Colorado and Nevada abolished felony disenfranchisement, however. In Maine and Vermont, which do not disenfranchise people based on a criminal conviction, people can vote from prison. “They’re still people, they’re still human beings, they’re still American citizens,” Matthew Dunlap, Maine’s Secretary of State, told me this month.

From Hawaii to New Mexico, activists are organizing at the state level to emulate Maine and Vermont’s model, with support from national civil rights organizations. Voting while incarcerated was also among the demands of last year’s prison strike, and it came to the fore in the presidential election when Senator Bernie Sanders stated his support.

No other candidate took Sanders’s position, but most at least embraced the stance that people’s rights should be restored once they are released from incarceration. Listening to these national debates, you would think that the view that formerly incarcerated people should vote is the default stance to which the Democratic party has sternly adhered.

But even that remains far from the case at the state level, at least before the organizing against disenfranchisement acquired increased visibility over the past year through efforts like Florida’s Amendment 4 initiative and the prison strike.

Of the 14 states with a Democratic government, five allow all formerly incarcerated people to vote. Colorado and Nevada will make it seven. But similar bills like theirs were killed this year in New Mexico and Washington, and have not advanced so far in Connecticut and New York. (Governor Andrew Cuomo did expand the voting rights of New Yorkers on parole in 2018 via executive order, but his approach kept complex layers including individualized review and a requirement that some people only be allowed to vote after 7 p.m.)

The synchronicity of Colorado and Nevada’s reforms, and the striking intraparty unity around them, makes them appear routine for Democratic legislatures. But that impression underscores the scale of this change. Reforms that until recently pushed the envelope of Democratic governance are more clearly coming into view as compromise measures, which are essential but still removed from universal suffrage.

“Restoring parolees’ voting rights” is an “important first step,” Representative Leslie Herod, who authored Colorado’s new law, said earlier this month. But “we need to consider restoring voting rights to those incarcerated” because “if anyone should be voting, it’s those who have been most affected by our laws.”

The flipside is that, in most of the states that permanently ban people from voting—even beyond the completion of their sentence—legislatures controlled by Republicans failed again this year to expand voting rights. That was the case for instance in Iowa or Mississippi, despite the support of some Republicans like Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds for incremental reforms. In Florida, the Republican legislature narrowed eligibility in May by shrinking the scope of Amendment 4, the ballot initiative implemented in January.

Clarifying eligibility

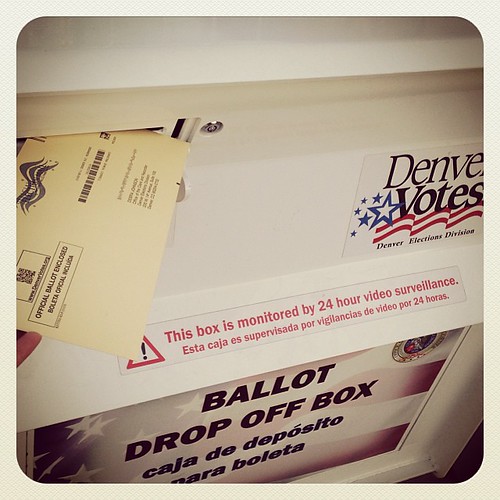

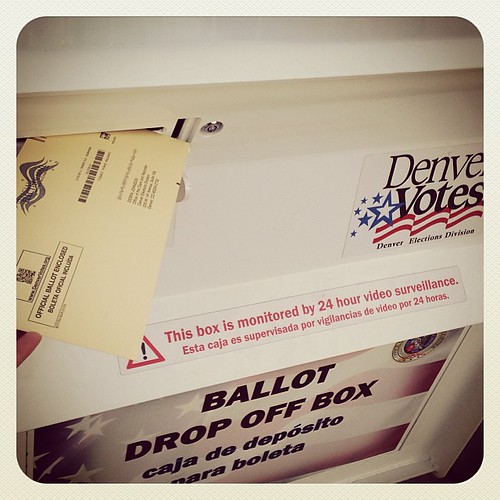

Reforms like Colorado and Nevada’s don’t just expand eligibility. They also clarify it. People involved in the criminal legal system must often face a dizzying maze of rules and stipulations to figure out whether they are entitled to vote, with the potential threat of prosecution looming if they get it wrong. In Nevada, for instance, you needed to incorporate factors like the level of your charges and the number of past convictions just to figure out if your rights were automatically restored. If not, you could always apply via a complex rights restoration petition.

State officials sometimes pointedly refuse to provide information to affected individuals.

Even as it leaves many people stripped of the right to vote, enfranchising anyone who is not presently incarcerated at least makes the situation more straightforward for communities outside the prison walls. “We need a law that is so simple and so clear that you don’t need to get legal advice,” Lonnie Feemster, the Nevada director of the NAACP National Voter Fund, told me in December. That’s a low bar that most states still have not crossed.