To Boost Turnout, Some Cities Just Synced Up Their Local Elections With National Cycles

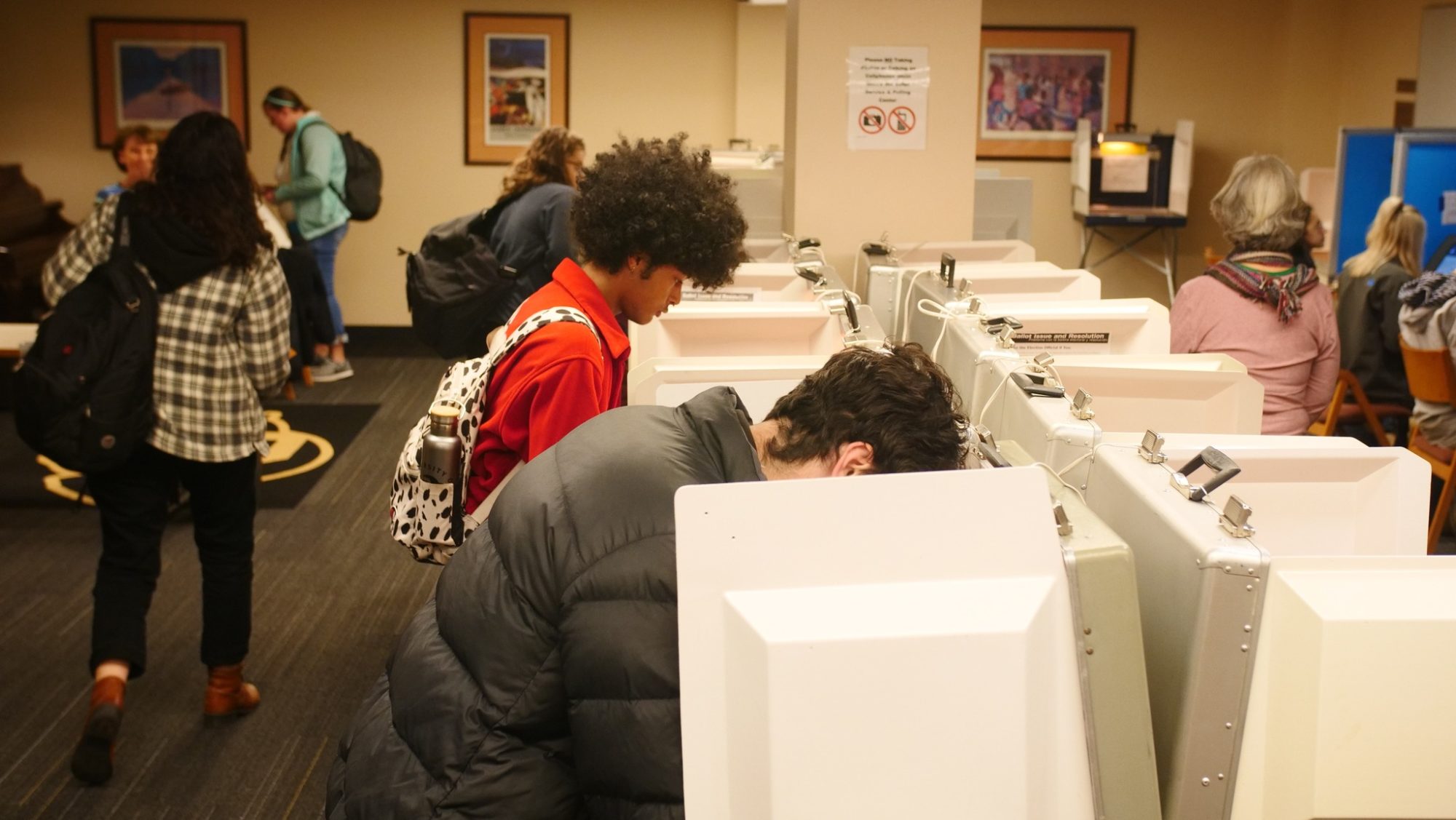

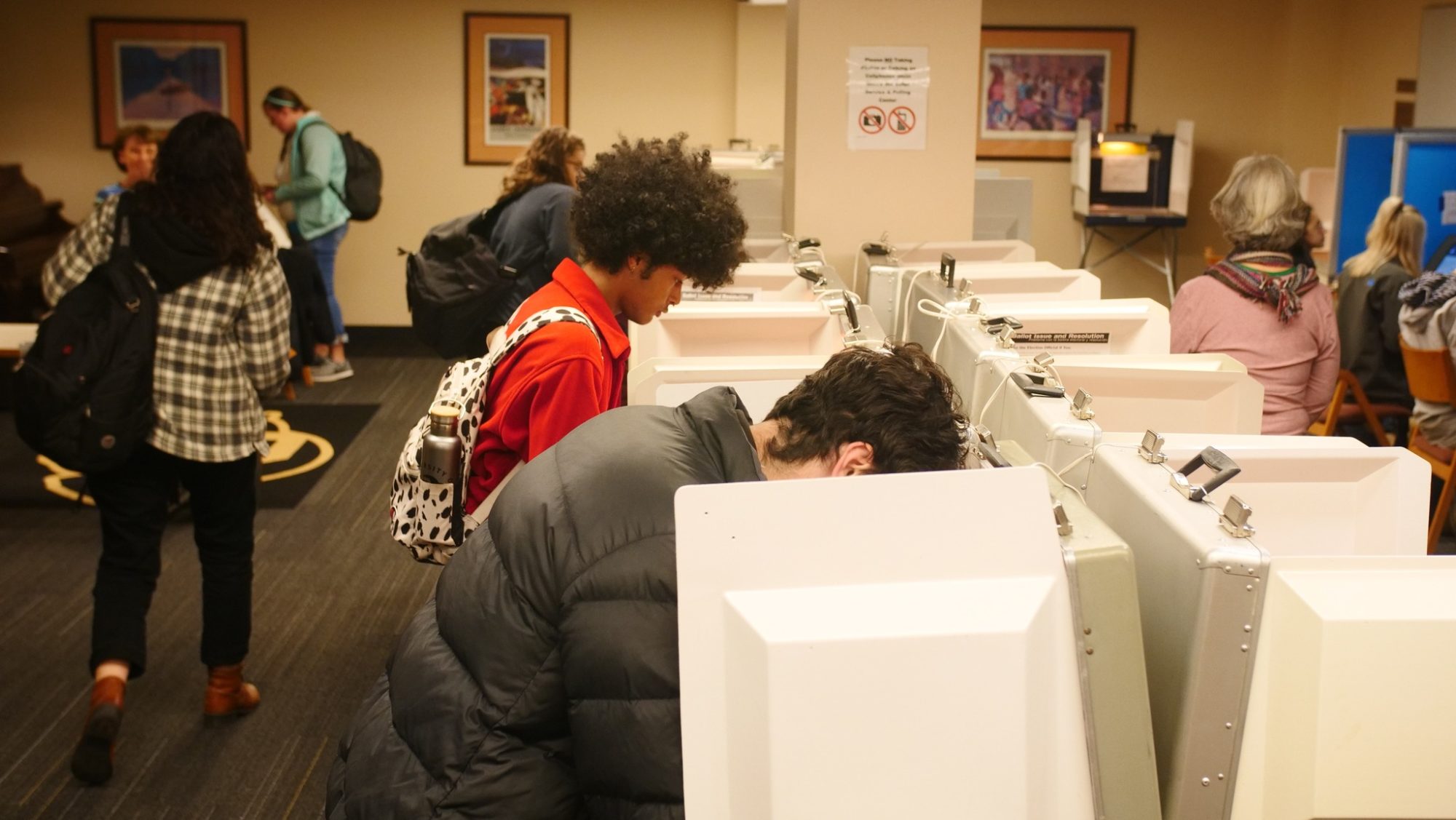

San Francisco and Boulder were among several places that voted to move elections from odd to even-numbered years. Advocates hope it will create electorates more reflective of city populations.

Alex Burness | November 22, 2022

Voters across the country approved ballot measures earlier this month that will move their local elections from odd-numbered to even-numbered years. The changes are primed to send turnout soaring in county and municipal races that typically draw the fewest voters.

Compared to the larger electorate that votes in a presidential or midterm year, off-cycle elections tend to see depressed turnout and draw a wealthier and whiter electorate, which can skew whose interests are spoken for in local politics, research shows.

“This reform makes it such that the power of the people is shared among the whole community,” Chelsea Castellano, an organizer who helped champion Ballot Question 2E to move city council elections in Boulder, Colorado, from odd- to even-numbered cycles, told Bolts. She said the status quo was “keeping voter turnout small and low and among certain groups that are typically pretty well represented on our council.” Question 2E passed easily, with almost two-thirds of the vote.

Election data show that turnout in Boulder hasn’t topped 51 percent in any of the odd-numbered years, when its municipal elections were held, between 2013 and 2021. In the even-numbered years of that same span, city turnout averaged 83 percent.

The drop-off is similarly dramatic in jurisdictions around the country that elect local leaders in odd-numbered years. In San Francisco, which also just passed a ballot measure to move its local elections to even-numbered years, turnout averaged 43 percent in off-cycle years but 80 percent in presidential election years.

Voters in nine other localities also approved measures this year to move their elections to even-year cycles, according to an analysis by Ballotpedia. They Include St. Petersburg, Florida; in King County (Seattle), Washington; and in San Jose, Long Beach, and five other California cities.

This wave of changes came among a series of reforms to election procedures that voters approved last week with an aim of increasing voter participation and turnout. In Connecticut and Michigan, voters codified more days of early voting into state constitutions. Voters in Oakland, California passed two measures enabling noncitizen voting in certain elections and creating a public funding program that allows more voters to financially back candidates of their choice.

In Boulder, Castellano and her allies hope that moving municipal elections away from off-cycles will engage more people of color, low-income earners, and students (Boulder is home to the University of Colorado), making for an electorate more reflective of the actual populace. Another local progressive organizer, former city council candidate Eric Budd, said he hopes this encourages candidates to run on issues that matter to a larger and more diverse set, as opposed to catering to the narrower group of off-cycle voters.

“Back when I was running,” in 2017, Budd said, “a lot of people were giving me the advice that you need to run a really moderate message, to appeal to homeowners.” Looking back at his own platform from that campaign makes him cringe, he added: “The way I was talking about occupancy limits was very guarded, the way I was talking about duplexes. … I think (2E passing) really shifts not only the people that are running, but the platforms that we’re running on.”

Budd and Castellano advocate for housing density and more flexible zoning as tools to build a larger, more transit-oriented housing stock in the name of climate action and improved socioeconomic and racial diversity, and to address the unaffordability of Boulder, where the median home listing tops $1 million. The other, unofficial political party in Boulder has worked to beat back density and development, prizing so-called “neighborhood character” above affordability strategies and has dominated most of the modern era until recently. The pro-density urbanists previously battled the city council to place a measure on the ballot to relax occupancy limits in Boulder, then lost in the off-cycle 2021 election. Budd said they started organizing for 2E three days after that defeat.

John Tayer, head of the local chamber of commerce, which took a neutral position on Question 2E, believes that progressives are more likely to hold onto power moving forward, with the help of voters more likely to turn out in the city’s new even-year election cycle. “There’s no question that this will—and I think it’s the intended purpose of the initiative—draw out a voter pool that would skew toward the youth, lower-income and renter populations, which would then probably align with candidates of a similar character,” Tayer told Bolts.

Opponents of 2E argued that off-cycle elections mean an electorate that is more involved. “Maintain an informed vote!” argued one longtime council member in the opinion pages of Boulder’s Daily Camera newspaper. Similar cries echoed from opponents of various related measures around the country.

For evidence that a larger and more diverse electorate can indeed change political makeup, the pro-2E organizers have looked to cities like Berkeley, California, and Ann Arbor, Michigan—like Boulder, two wealthy, small cities with major universities, where municipal elections have flipped from odd- to even-numbered years.

In Ann Arbor, this change has had the effect of wiping out all council members who strongly resist housing density and development. That city also requires partisan markers for local candidates which means that, in even-numbered years with higher turnout, conservatives have an even harder time winning in the liberal stronghold. One former Ann Arbor council member, a longtime Republican, said in 2020 that she registered as a Democrat just to have a chance. She lost by 20 percentage points that year. (Boulder’s elections remain non-partisan, though there are so few Republicans in town that one needn’t squint to discern most candidates’ affiliations based on their policy proposals.)

Surveying the nation, researchers at the University of California, San Diego found shifts in power are not surprising, given the “unequivocal” finding that, “Across the nation, turnout in cities with on-cycle elections is dramatically higher than those with off-cycle elections.” Moving municipal elections to presidential years produces an average turnout boost of 29 percent, the researchers wrote, as higher-profile races draw more people to ballot boxes in those years.

Inspired by this data and the passage of 2E, Colorado state Representative Judy Amabile, a Democrat of Boulder, told Bolts she is now working on a bill to lift the state prohibition on school board elections in even-numbered years.

And just to the east, in the city of Aurora, progressive council member Juan Marcano is pushing for changes that he believes will better align the local government with its broader citizenry. Aurora, with a population of nearly 400,000 people and greater racial and ethnic diversity than any other city in the state, is clearly liberal: Its congressman, U.S. Representative Jason Crow, is a Democrat who just coasted to reelection. Its state legislative delegation is almost entirely Democratic. And yet the city council, elected in non-partisan races in odd-numbered years, is controlled by conservatives. In the most recent municipal election there, turnout was only at 30 percent, city data show. Nearly three times as many registered Aurora voters turned out for the 2020 presidential election, the Sentinel newspaper reported.

Aurora has had some exceptionally close local elections in recent years—most notably, the former Republican U.S. Representative Mike Coffman won the 2019 mayoral race by about 200 votes over Democratic local NAACP chapter president Omar Montgomery—and Marcano believes his side stands a good chance at flipping power in November of 2023. If it does, he said, he’d like to refer to voters amendments to the city charter that would make local elections partisan and place them on even-numbered years.

“They know that if we had the opportunity to actually have more attention shown to municipal elections, coinciding with when more people are turning out, that they would likely not prevail, to put it politely,” Marcano told Bolts. “They’re relying on low turnout and the disproportionate white, wealthy and conservative voters that turn out for municipal elections.”

The idea, he said, is to meet voters where they’re at. He likened it to designed sidewalks and bike trails.

“You’re going to find the social trails out in the world, and that tells you where the sidewalks should be,” Marcano said. “What we’re seeing from our residents is they want to vote in even years. That’s when they turn out, so it’s our responsibility to allow people to follow the path of least resistance and to be heard when they want to be heard.”

Marcano won his race, in 2019, by 232 votes, or less than 2 percent. The state representative whose district roughly overlaps with his Aurora ward, a Democrat named Iman Jodeh, just won re-election by 28 percentage points.

Those striking numbers aren’t lost on Republican Dustin Zvonek, an Aurora council member who opposes even-numbered and partisan local elections. He said such changes would make municipal politics less personal and more nationalized, and rob city campaigns of the spotlight they presently enjoy during off-cycle elections.

“If you’re just about getting partisan majorities, I understand why you’d want to do this,” he told Bolts. “You can say there are more people that vote overall, so that’s better. But I guess it depends on what you’re looking for.”

Were Aurora to make the moves Marcano seeks, Zvonek added, there is little question that this liberal city with conservative local leaders would elect a more progressive council. “I absolutely believe that,” he said.