How Do New Jersey Counties Still Partner with ICE?

New Jersey attorney general limits local cooperation with ICE, postpones some decisions.

Daniel Nichanian | December 6, 2018

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

New Jersey’s attorney general limits local cooperation with ICE, postpones some decisions

New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal on Nov. 29 released a directive curtailing local law enforcement’s contact and cooperation with ICE. It bars police, sheriffs, and other public authorities from assisting ICE operations, inquiring into someone’s immigration status, and sharing with ICE space and databases that aren’t otherwise public. It also helps individuals know their rights before talking to ICE. “Folks might be speaking to [ICE] out of a belief that they are required to,” Alexander Shalom, a senior supervising attorney for the ACLU-NJ, told me. “No longer will immigrants … be duped into the conversation.”

“The document is going to go a long way to repairing trust in immigrant communities,” Shalom said. “The directive is an extraordinary step forward for immigrant rights in New Jersey,” Sara Cullinane, the director of Make the Road New Jersey, an advocacy group for immigrant and working-class communities, told me.

The document sidesteps or only partially restricts three forms of cooperation, which demand more attention.

1. 287(g)

This program gives local officers the authority to research people’s statuses and notify ICE.

Counties typically join 287(g) through a contract between their sheriff and ICE. Grewal’s directive does not terminate existing 287(g) contracts, nor does it conclusively prohibit new ones. It blocks counties from acting unilaterally, requiring the attorney general’s authorization if they wish to create or renew a 287(g) partnership.

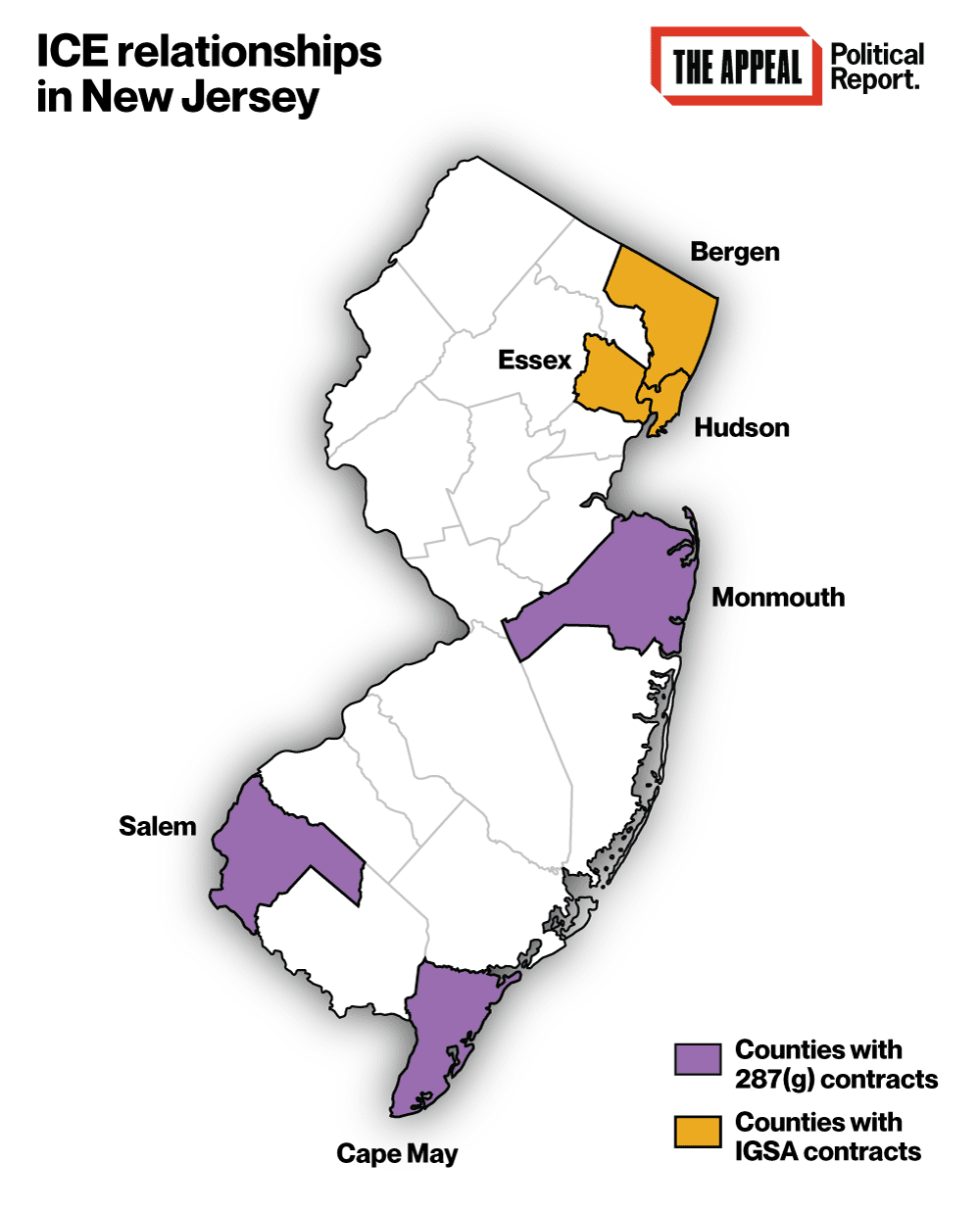

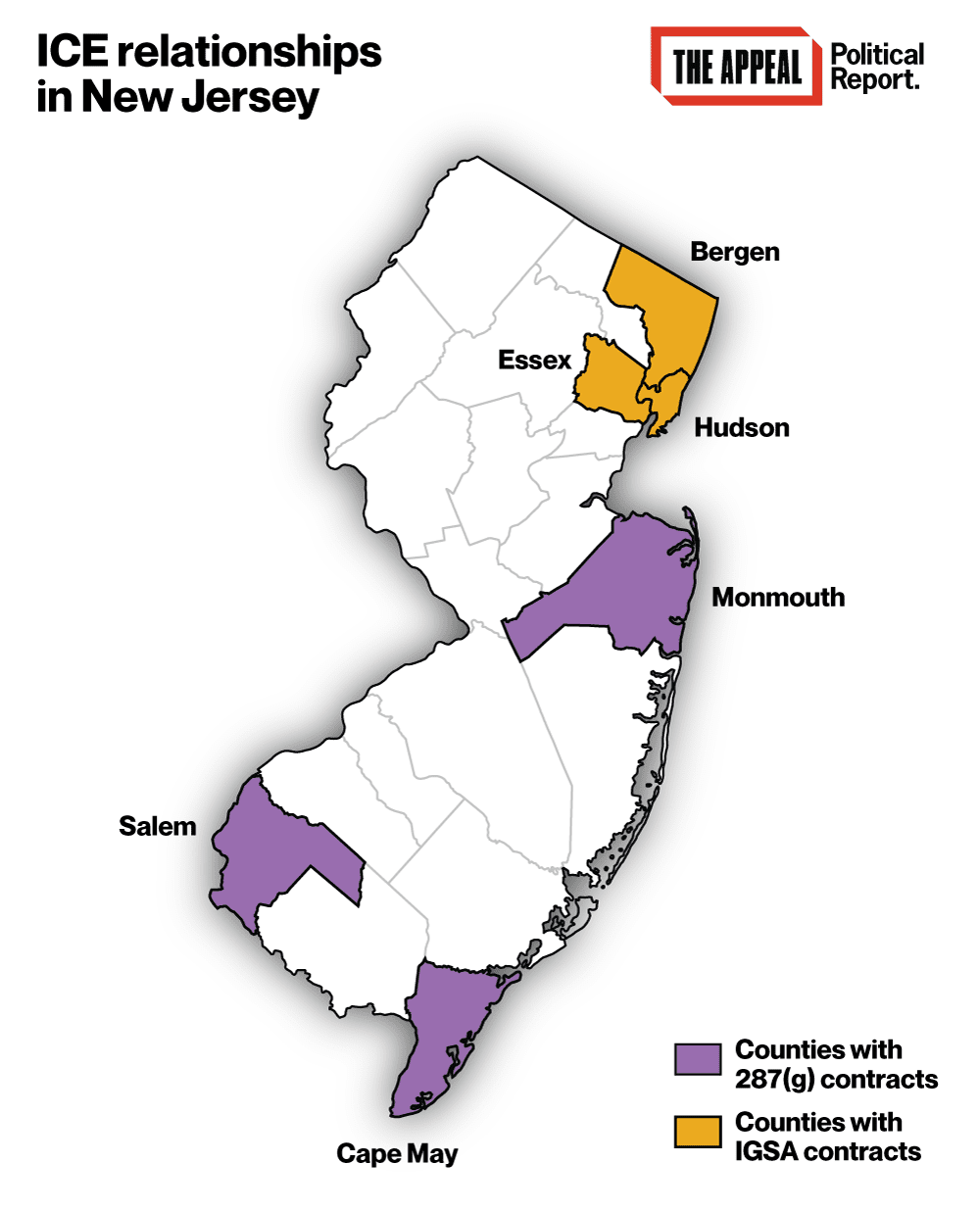

Three New Jersey counties have 287(g) agreements: Cape May, Monmouth, and Salem. All three have a Republican sheriff: Robert Nolan (up for re-election in 2020), Shaun Golden (up in 2019), and Chuck Miller (who was just re-elected and is up in 2021), respectively. Each county’s 287(g) contract expires June 30, 2019. So the question of what Grewal would do if the counties seek to renew their participation will come to a head next year. I asked Grewal’s office under what circumstances he would grant a renewal. “The directive does not list specific criteria. I am not going to go beyond what is in the directive,” a spokesperson responded via email.

“We were hoping that they would get rid of 287(g) completely,” Johanna Calle, the director of New Jersey Alliance for Immigrant Justice, said while praising the directive overall. “We’re going to have to be vigilant and pressure the attorney general to not allow [contracts] to be renewed.”

2. Detainers

According to a report by Erika Nava of New Jersey Policy Perspective, nearly all New Jersey counties voluntarily honor ICE detainers. These are warrantless requests for jails to detain people who are already in custody beyond their scheduled release dates, even if they post bail. Grewal’s directive prohibits counties from honoring detainers in many circumstances. It does make exceptions, for instance for individuals charged of “violent or serious offenses” (the directive contains an enumerated list) or individuals against whom a judge has issued a final order of removal. Counties can notify ICE of such individuals’ times of release and detain them for ICE through the end of the day. Nava told me that she wished the prohibition on detainers had no carve-outs, though “considering where we were before, it’s tremendous progress.”

3. IGSA contracts

Bergen County, Essex County, and Hudson County (three large counties in northern New Jersey, all of which are currently governed by Democratic politicians) have contracts with ICE to detain individuals that ICE has arrested in exchange for payments. Grewal’s directive does not address these contracts, which can remain in place.

In July, WNYC radio’s Matt Katz reported that ICE was paying these three counties a combined $6 million a month to detain thousands of immigrants. This revenue has surged because of increased immigration enforcement under Donald Trump. Officials argue that they would need to increase local taxes and lay off correctional officers without these payments; opponents denounce this as profiting off of deportations. Hudson County freeholders unexpectedly renewed their contract in July; amidst protests they reversed course and announced that they would look to exit the contract by 2020.

Some groups, especially ones like the Bronx Defenders and the Brooklyn Defender Services that provide legal services to immigranfs, oppose canceling these contracts. They argue that it would be harder to mount an adequate defense if ICE moved people far from the region. “We recognize both sides of that argument,” Shalom of the ACLU-NJ told me. “Providing people with access to counsel and proximity to loved ones is critically important. We also recognize the financial incentives to jail more and more immigration detainees are perverse and often lead to gross mistreatment.”

Public officials have also argued that immigrants would be treated worse elsewhere. “I take great pride in knowing they’re in the best possible facility they could be,” Bergen County’s then-sheriff, Michael Saudino, said in July. Saudino resigned in October, and incoming sheriff Andrew Cureton stated in a new interview with the Bergen Record that he favored keeping the contract. “We’re going to continue what we’re doing, have the contract in place, provide the best service we can provide for the detainees,” he said.

But some immigrant rights advocates reject the use of this language from public officials regardless of their own views on the overall question of whether the contracts should be maintained. “What we have seen is that leaders, freeholders, county executives have used real concern brought by legal providers as an excuse to maintain their financial gains,” Calle told me. She added that officials “use our own talking points against us. We can acknowledge that legal providers are raising valid concerns, and hold legislators and elected officials accountable. They could do so much to improve the lives of people they’re detaining.” Reports in WNYC and NorthJersey.com have revealed poor detention practices in Bergen County, for instance. A lawsuit filed in November alleges that staff in the Bergen jail withheld medication from an immigrant detainee.

Nava said that one way for New Jersey officials to show their care for legal representation is to increase the resources allocated to a new legal aid program, since the state still lags New York. She also called on the legislature to codify the attorney general’s changes into law. “That’s one way to make it less possible for future administrations to repeal it,” she noted.