Mississippi Sets Up Its DA Elections, and Only Five Are Contested This Year

Head of state reform group jumps in Jackson’s election. But a DA about to face the Supreme Court is unopposed.

Daniel Nichanian | March 6, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Mississippi’s local elections are still nine months away, and already 16 of the state’s 22 district attorneys are guaranteed to win re-election because no one filed to run against them.

One of them is Doug Evans, the DA of the Fifth District since 1991. A Democrat, Evans has drawn national attention this year as one of the protagonists of the podcast “In the Dark” (produced by American Public Media), which documents how he has put a man named Curtis Flowers on trial six separate times over the same murder allegations. Later this month, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear Flowers’s appeal against Evans’s sustained pattern of excluding African Americans from juries.

Even if the Supreme Court overturns Flowers’s conviction, which would be Flowers’s sixth successful appeal, his fate will still be in the hands of Evans, who will be in office for the foreseeable future and who could try him for a seventh time.

This is the fourth consecutive election where Evans is unopposed. This is a common pattern in Mississippi. In addition to the 16 incumbent DAs against whom no one filed to run against this year, there is a seventh candidate who isn’t even an incumbent and yet is now sure to win: Assistant District Attorney Daniella Shorter is the only candidate running to replace the retiring Alexander Martin in the 22nd District. It is also a common pattern nationwide. The majority of Wisconsin counties haven’t held a single contested DA election this decade, for instance.

The difficulty in fielding candidates is an obstacle to reformers who have increasingly used local elections to elect DAs who defy the job’s traditional tough-on-crime mold. That was the case in Mississippi in 2015, when Scott Colom won the 16th District on a reform-oriented platform that de-emphasized incarceration for drug offenses. Colom is also unopposed this year.

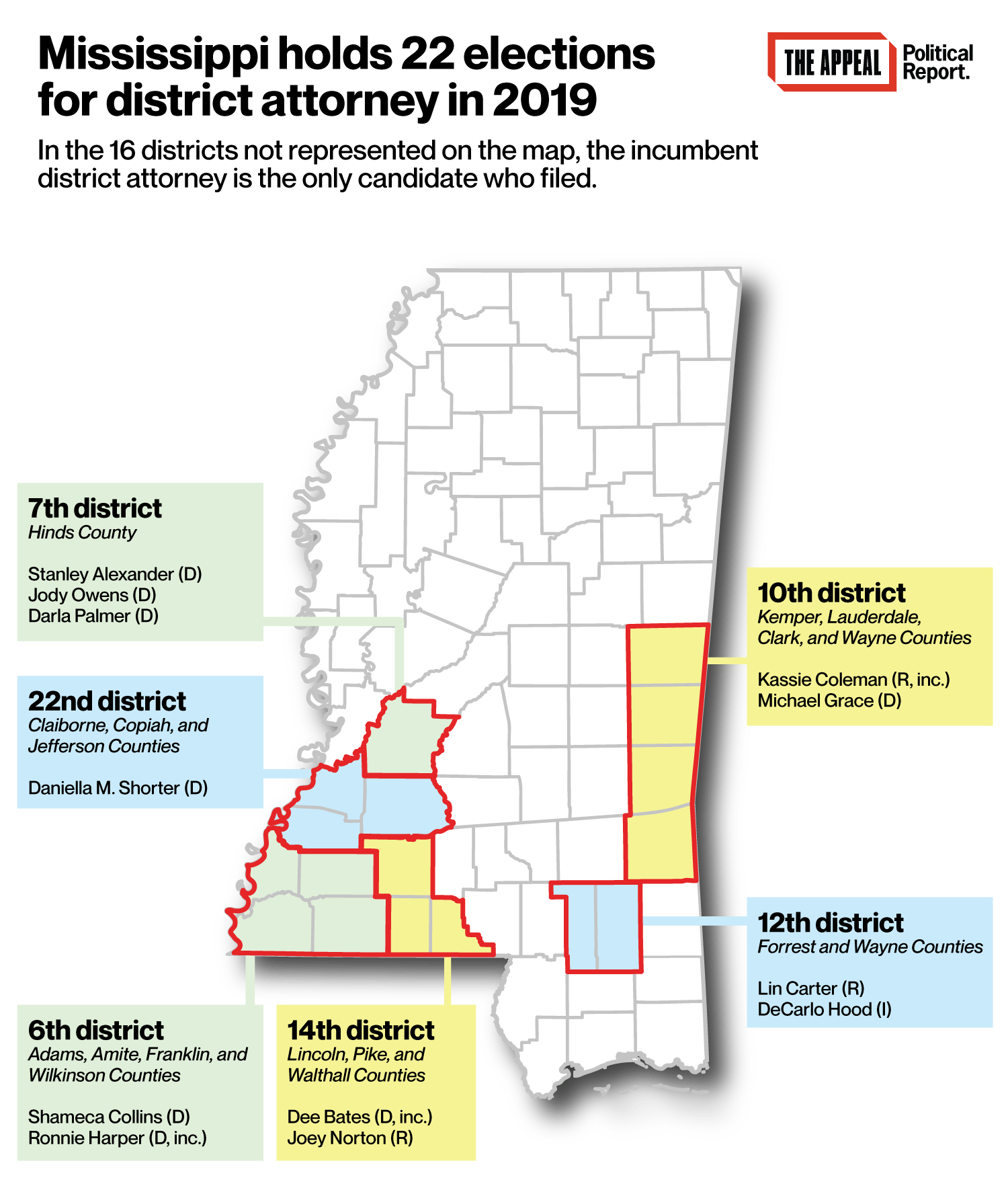

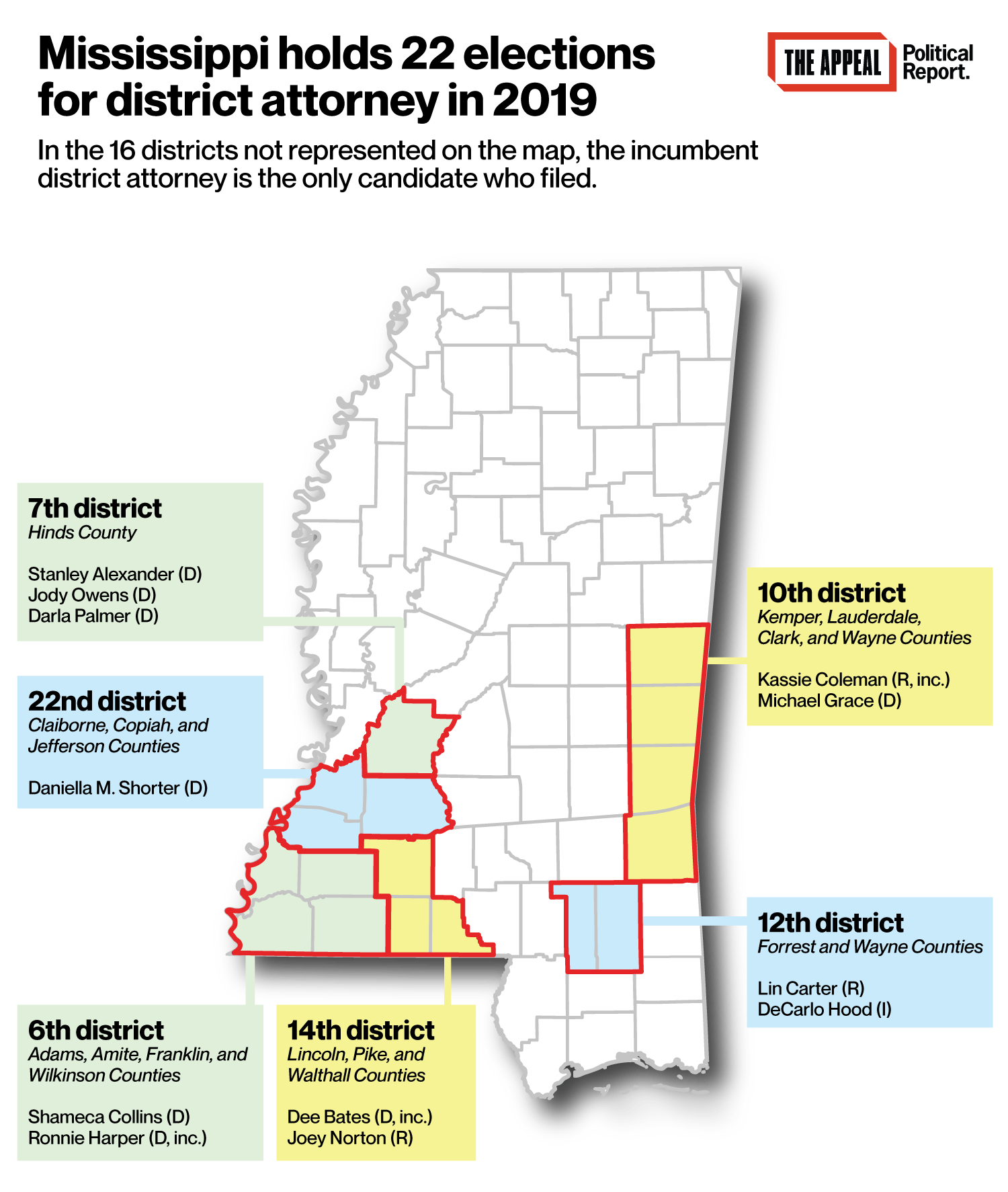

All of this still leaves five elections that will feature some competition this year. Three (the 10th, 12th, and 14th districts) will be contested only in November’s general election; the other two (the sixth and seventh districts) will be decided in the August Democratic primaries.

You can review the full list of DA candidates in this Political Report master list. The map below provides details on those elections that might produce a change in leadership this year:

From the standpoint of criminal justice reform, the year’s marquee election is likely to be the one to replace Robert Shuler Smith, the DA of the Seventh District, who is running for governor.

The district contains only Hinds County, the state’s most populous county and home to Jackson. The county’s legal system has drawn investigative fire. In 2016, the Clarion Ledger exposed “the often staggering amount of time” the county was detaining people before indicting them, with one person held 467 days for a burglary for which he was never indicted, a situation that led a local judge to confront Smith’s office last year. The three candidates running to replace Smith are Stanley Alexander (an assistant attorney general who also ran in 2015), Jody Owens (the chief policy counsel of the Southern Poverty Law Center and managing attorney of the group’s state office), and Darla Palmer (a Jackson-based defense attorney). All are running as Democrats.

As managing attorney of the SPLC’s Mississippi office, Owens has played a role in pushing for reform in the state. In 2015, he penned an essay in Politico Magazine on what he called a “civil rights crisis in America,” namely “a ‘school-to-prison pipeline’ that sucks vulnerable children out of the classroom at an alarming rate and funnels them into the harsh world of police, courts and prison cells.” And in a lengthy 2018 interview with Amy Goodman on Democracy Now, he discussed his group’s litigation alleging prison abuses, problems with private prisons, and the prison strike against forced labor. “The only time a suppressed group of individuals, whether they be prisoners or civil rights workers, will ever have any rights is if they take ownership of it,” he told Goodman. Owens has also been a part of the SPLC’s ongoing lawsuit challenging the state’s disenfranchisement rules.

Mississippi’s 22 DA elections will take place under harshly exclusionary circumstances since the state imposes a lifetime voting ban on anyone convicted of one of a list of 22 offenses. According to a Sentencing Project study, 9 percent of the state’s voting-age population, and 16 percent of the state’s Black adults, were disenfranchised as of 2016.

This means that the state’s 22 prosecutors will be elected—or re-elected—without the input of the hundreds of thousands of Mississippians who have been most affected by the decisions and policies of their offices. “We can’t have true criminal justice reform until we restore the voting rights of formerly incarcerated individuals so they can have their full citizenship back, and their right to vote,” state Representative Kabir Karriem told me in February of efforts to change Mississippi laws.