Why New Jersey’s Sheriff Elections Matter

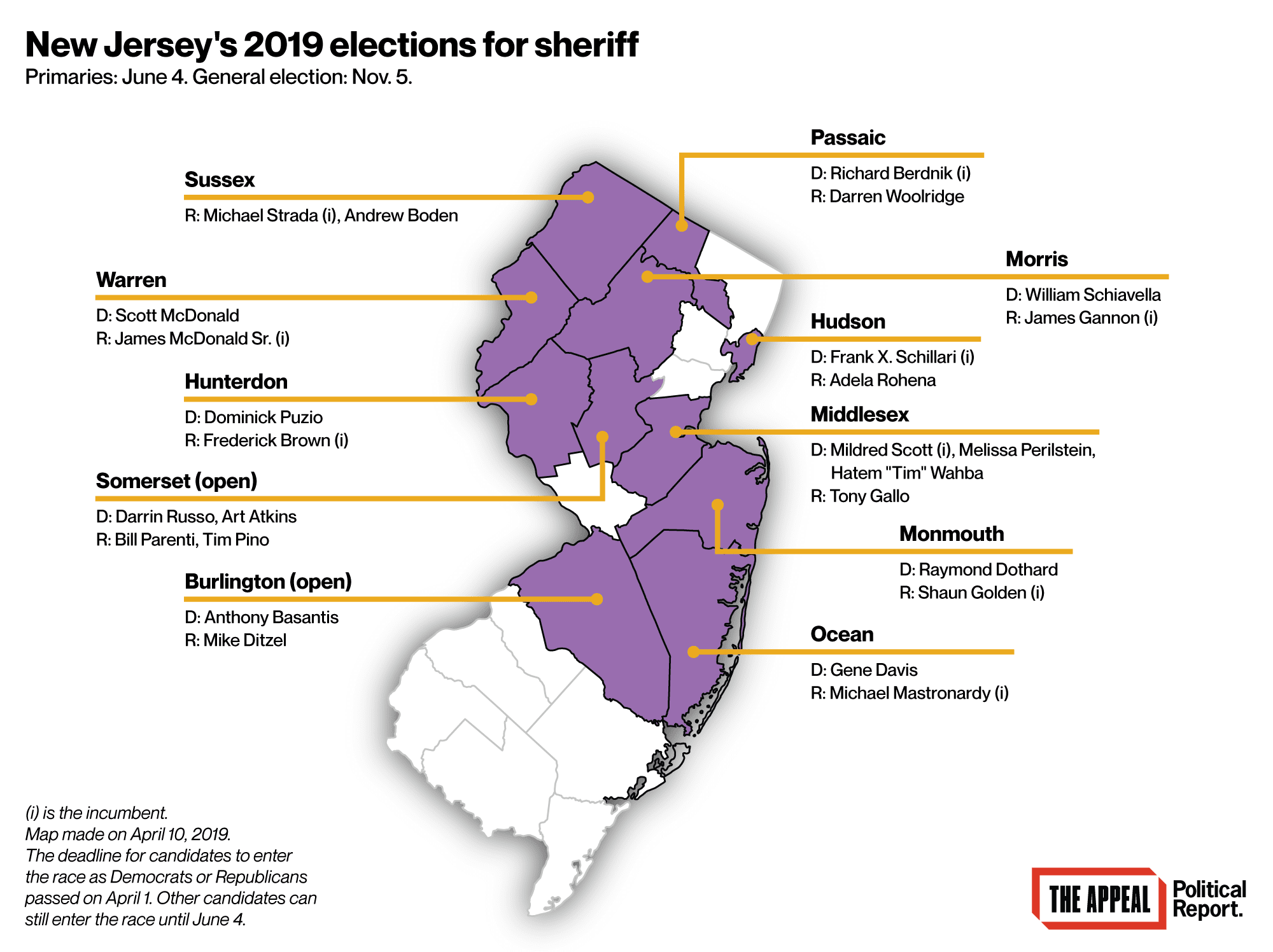

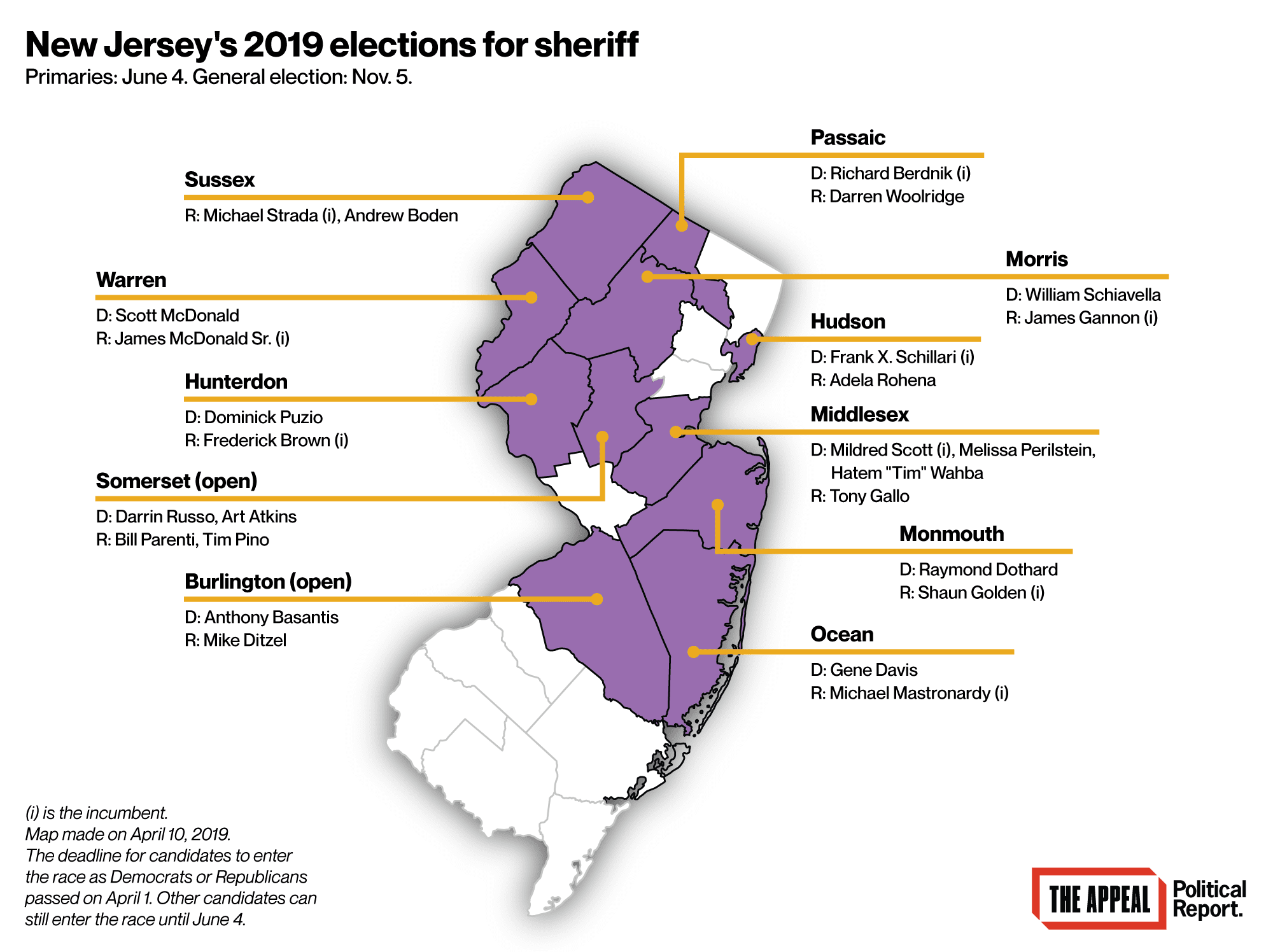

Eleven New Jersey counties vote for their sheriff this year. These elections could shape immigration policy, law enforcement, and jail conditions.

Daniel Nichanian | April 10, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Eleven of New Jersey’s 21 counties are voting for their sheriff this year. These elections could shape immigration policy, law enforcement, and jail conditions, and each has drawn multiple candidates—a striking fact since local elections often go uncontested.

The filing deadline for Democratic and Republican candidates passed last week. As part of our ongoing coverage of 2019 local elections, the Political Report previews some issues that they will face. Independents have until June 4 to file nominating petitions; June 4 is also the day of the Democratic and Republican primaries.

Twenty-three of the 26 candidates are men. Mirya Holman, a political science professor at Tulane University who studies sheriffs and women in politics, told me that this imbalance is if anything less than one might expect because only one percent of sheriffs nationwide are women. “Sheriff candidates are most likely to emerge out of a policing background and police in the United States are much more likely to [be] men,” she said via email. “There’s also a masculinized ethos associated with the office, both from historical patterns and from our national mythology around the office.”

Jail conditions

In a majority of New Jersey counties, the responsibility of running the local jail lies not with the sheriff but with a correctional director appointed by other county officials; that is for instance the case in Hudson County, one of the state’s most populous jurisdictions. However, sheriffs do run the jail and therefore shape detention conditions in five of the counties voting for sheriff this year: Monmouth, Morris, Passaic, Somerset, and Sussex.

Poor detention conditions are major contributors to the high number of jail deaths nationwide. A WNYC investigation reported in November that “New Jersey jails have the highest per-capita death rate among the 30 states with the largest jail populations” but that this has garnered “little attention from the state.” The reporters raise questions about the quality of medical care, and look into a private provider that many county jails contract with.

Efforts to restrict solitary confinement have stalled so far. Governor Chris Christie vetoed a bill in 2016, and legislation introduced in the current session has yet to move forward. The new bill would bar solitary confinement for some groups like pregnant women, and limit it to 15 consecutive days for anyone else. Until legislation passes, or until lawsuits force reform, the officials running carceral centers—including sheriffs in the case of some jails—retain wide discretion over how to use this practice.

Sheriffs can also be gatekeepers for substance use treatment. Jails can provide medical-assisted treatment, and programs can be pursued elsewhere as well. Last week, Morris County Sheriff James Gannon announced an initiative to help people access recovery programs; another county program involves distributing naloxone, an overdose reversing medication. But some sheriffs cite their jails’ drug-related services to oppose other aspects of criminal justice reform. Monmouth County Sheriff Shaun Golden has faulted bail reform on the grounds that people who are promptly released pretrial do not get screened for substance use problems.

Immigration

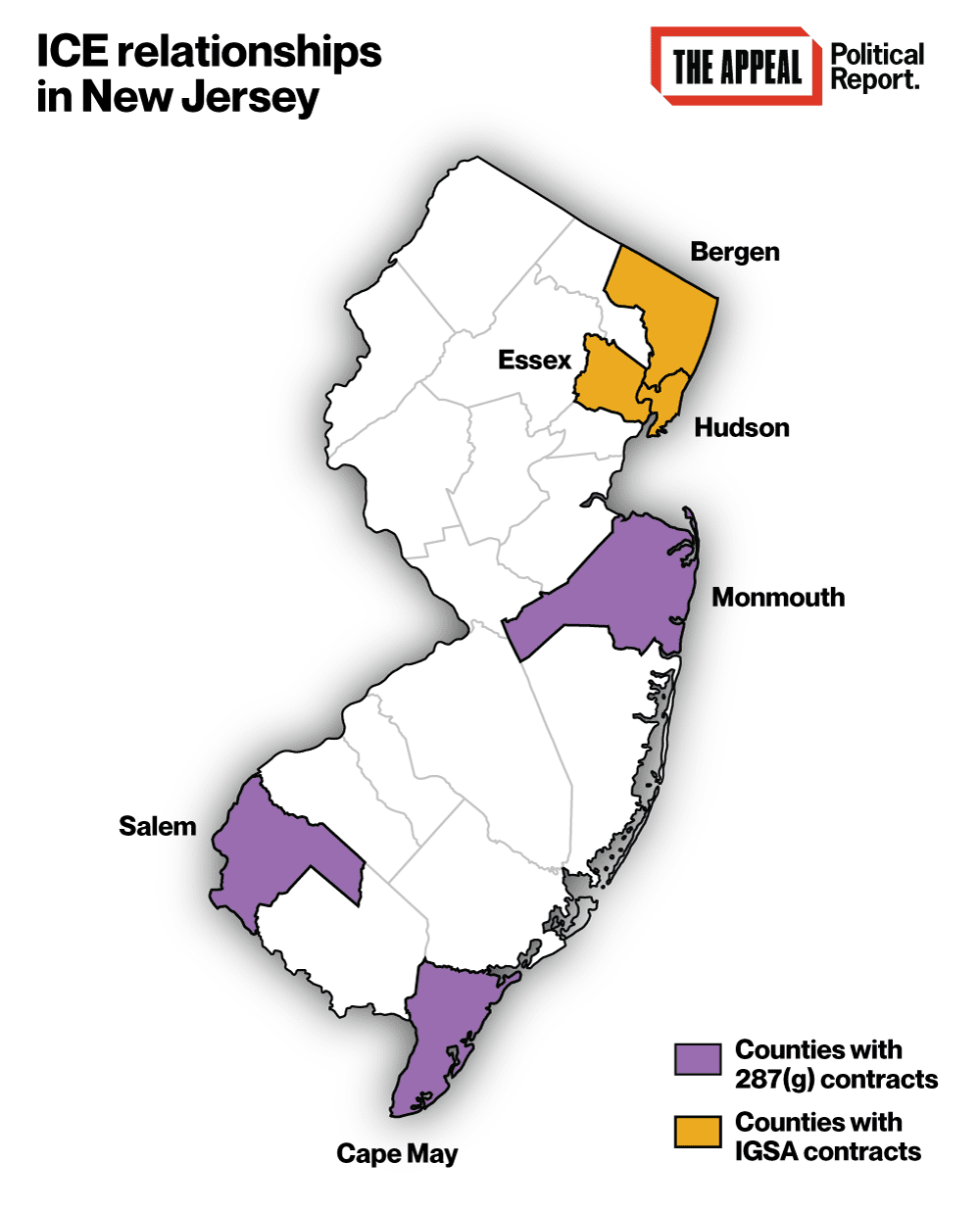

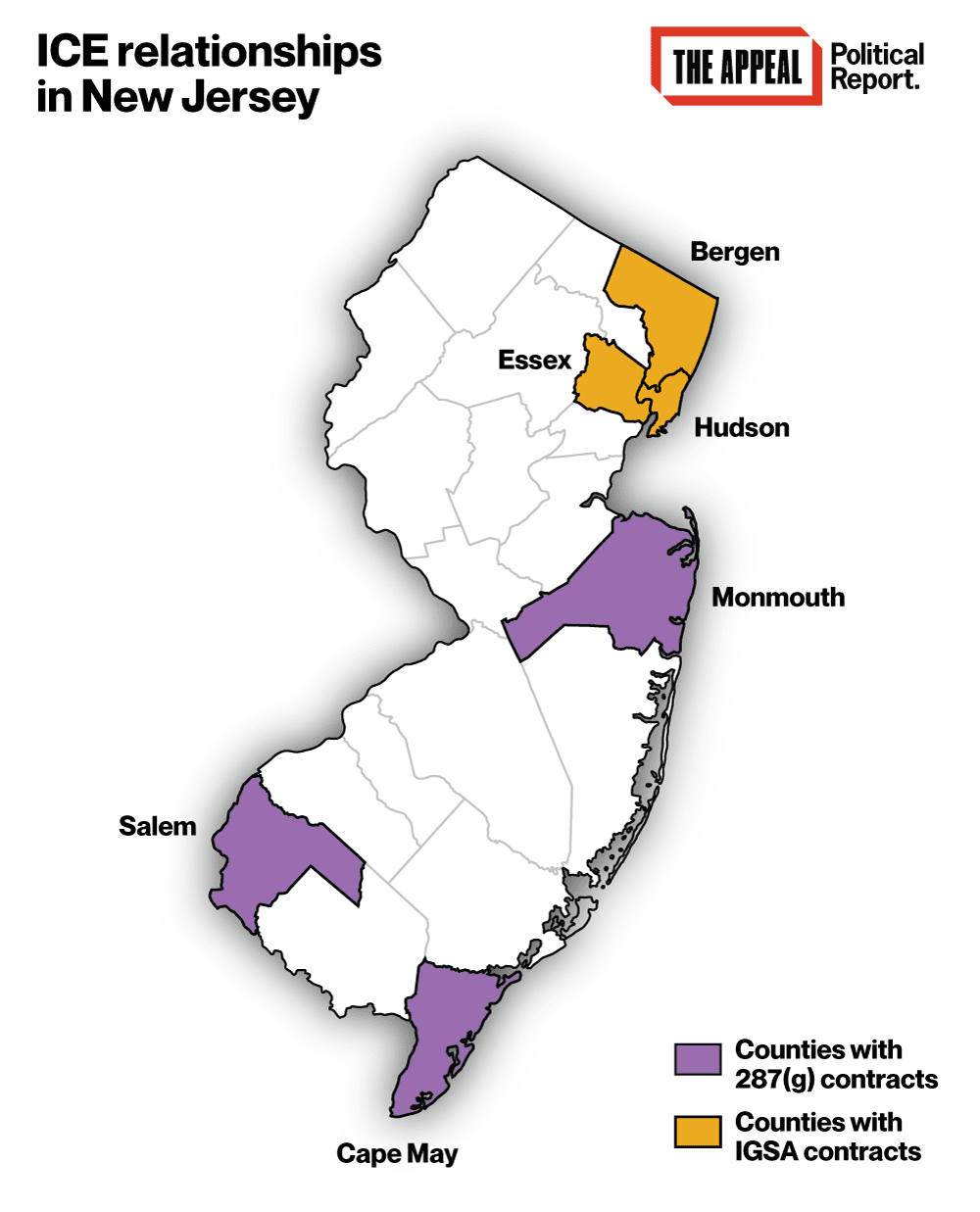

New Jersey may be a blue state, but county governments have been friendly to ICE. The state attorney general issued a directive in November that restricted local cooperation with the federal agency. It bars law enforcement from assisting ICE operations, inquiring into people’s immigration status, and in some circumstances holding people based on a warrantless ICE request. Where does this leave sheriffs?

The directive does not outright bar ICE’s 287(g) program, which gives local law enforcement the authority to act like federal immigration agents toward people in their custody. Sheriffs now need approval from the attorney general to sign a new 287(g) contract or extend an existing one. Still, they retain a crucial role since they can end a contract at any moment or apply for a new one.

Three New Jersey sheriffs have joined 287(g). Only one is up for re-election this year: Golden, the Republican incumbent in Monmouth. Raymond Dothard, his Democratic challenger, did not respond to an inquiry into his position on the contract. Golden’s office also did not reply to an inquiry into whether he plans to renew the current contract, which expires in June.

Other sheriffs who run jails could apply for new 287(g) contracts. They could also seek other forms of partnerships, such as renting jail space to ICE.

A sheriff’s politics matter even in areas where the directive cuts their discretion. After all, they are responsible for ensuring that their deputies abide by the new restrictions on what questions they can ask and what operations they can partake in.

Erika Nava, an analyst at the New Jersey Policy Perspective, told me that sheriffs “have to implement the guidelines, but in terms of how well it’s implemented, it’ll depend on how sheriffs instruct their staff. … If you don’t train officers correctly, if you’re not holding them to a high standard on the directive, chances are they are going to mess up.” Johanna Calle, director of the New Jersey Alliance for Immigrant Justice, also said that “their views on the relationship with ICE matter… If ICE comes to your facility and you believe that ICE is a great agency, you might collaborate with them.” Calle noted that sheriffs for instance oversee courthouses. “In theory a sheriff’s officer should not be transferring someone to ICE agents,” she said, “but that doesn’t mean that they won’t do it.”

Some of the sheriffs running for re-election this year have defended ICE cooperation. There is Golden, who participates in 287(g). In Morris County, Gannon has opposed efforts to pass local sanctuary reforms, and has said that “asking local law enforcement officers to effectively ignore federal law is problematic on a number of levels.” And in Hunterdon County, Sheriff Frederick Brown has championed President Trump’s immigration policies and echoed the president’s rhetoric, blaming “uncontrolled, illegal immigrants” for wage losses, the opioid crisis, and murders.

Calle believes that all candidates should address whether they “think there is a role for sheriffs and local law enforcement to support federal enforcement,” and whether they would be open to entering new partnerships that ICE may come up with. “It has to do with values,” she said.