"It Undermines Communities to be Seeking Convictions for Nonviolent Misdemeanor Offenses:" An Interview with Tracey Lenox

Daniel Nichanian | May 23, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Tracey Lenox, a candidate for commonwealth’s attorney in Virginia’s Prince Williams County, talks to the Political Report.

Daniel Nichanian

You can visit the Political Report’s broader coverage of the 2019 elections here.

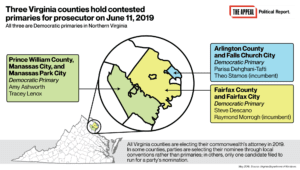

The prosecutorial election of Prince William, a populous county in Northern Virginia, is up for grabs for the first time in decades. Commonwealth’s Attorney Paul Ebert, a Democrat whose office is known for frequently pursuing the death penalty, as well as for findings of misconduct, is retiring after 51 years in office. Amy Ashworth and Tracey Lenox are running to replace him in the June 11 Democratic primary.

Tracey Lenox (Photographer: Mark Finkenstaedt)

This week, I talked to Lenox, who works as a criminal defense attorney, about her politics. She described “criminal justice reform” (making “a significant change in the way Prince William handles equal justice issues and justice reform”) as an impetus behind her candidacy, and I asked for details about what this change would consist in. She said she would “divert and dismiss” most “nonvictim misdemeanor charges,” including possessing marijuana and driving with a suspended license. It “doesn’t make sense” to “convict people of offenses like that,” she said. She indicated that she would rather use pre-conviction diversion programs than to decline these cases. Lenox also discussed wanting to set up a restorative justice program and open file discovery, and she explained that the death penalty is used inequitably. She did not rule out seeking it, however. I also asked her how her emphasis on reform fits with the endorsement she received from Ebert, the incumbent, and how she would ensure her office shares exculpatory material.

The Political Report has also published an interview with Ashworth, Lenox’s opponent in the Democratic primary, who is a private attorney and a former prosecutor in the commonwealth’s attorney’s office. The winner of this primary will then face Mike May, a former county supervisor who has secured the GOP nomination, in November.

The interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Commonwealth’s Attorney Paul Ebert has made comparatively frequent use of the death penalty. If elected, would you ever seek the death penalty, and if so in what circumstances would you do so?

I do not in principle object to the death penalty. Having said that, I believe that if you cannot apply the death penalty in a fair and equitable way, you shouldn’t seek it. We have lots of evidence that we don’t do a very good job applying it equitably. I would have to have assurances and confidence that we can apply it equitably, and not just the prosecutor’s office. It’s not even enough that the prosecutor knows how to equitably pick the right case, it’s also troublesome to me about the way we have to instruct juries about it.

So would I in principle object to the death penalty? No. Would I seek it myself? I can’t rule it out, but I’d have to have assurances that it can be done in an equitable way. And if you can’t do equitably, you shouldn’t do it.

Can you clarify what kind of assurances you have in mind? I’m aware you have prosecuted these cases. There are research laying out the equity issues with the death penalty, so what does it look like for you to have these assurances over the next few years?

I don’t know if we could, I’m not confident that we could.

The United Supreme Supreme Court is who makes the decisions about interpreting what the Eight Amendment means, that’s the prohibition on cruel and unusual punishments. They have interpreted what it means, for example, to have future dangerousness as a component of an offense. Future dangerousness is necessary in order for a jury to find that the death penalty is appropriate punishment. But the Supreme Court’s law, the cases that interpret what future dangerousness means, don’t allow the jury for example to hear that people who are incarcerated and on death row actually have a minuscule recidivism rates. They’re not allowed to hear that actually there is no future dangerousness if you’re on death row. That’s an example of it, if you can’t give jury information that will give them the full picture of the case, and the defendant, and his background, and his wife, and his future dangerousness going forward, then how can you be convinced that the jury will make the right decision to seek death or not. That’s just one example. I don’t have control over that, over what the SC decides future dangerousness looks like.

I have great concern over the ability to apply the death penalty cases fairly. I wouldn’t rule it out, I don’t think I can do that. But I have very strong feelings having been a criminal defense attorney my entire 25-year career and fighting on behalf of my clients for fair and equitable treatment by the court system, fighting about justice reform in my day-to-day life for 25 years. I am just not convinced how you apply to death penalty fairly.

Prosecutors in Virginia and elsewhere have announced new policies to altogether decline to prosecute certain categories of cases or else to expand pre-charge diversion programs that don’t rely on filing charges or obtaining convictions. Are there specific offenses that you would favor either altogether declining to prosecute, or for which you would like to expand opportunities for pre-charge diversion?

Absolutely. Super easy ones: driving on suspended, first-offense shoplifting, possession of marijuana. Disorderly conduct is another one that is utilized in a very destructive way. So the majority of nonvictim misdemeanor charges.

What would that exclude? It would exclude assault and battery, which is a Class 1 misdemeanor, it would probably exclude at least right now driving under the influence charges, though I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that for low-level driving under the influence you could institute a diversion program. But you have to be very careful about public safety. For possession of marijuana, I don’t think it should be decline to prosecute when there is a child that’s smoking pot or possessing marijuana. It concerns me having marijuana on school property, whether you’re smoking it or not. You should be an adult, just like alcohol or tobacco.

Almost any Class 1 misdemeanor that’s not a crime of violence or doesn’t have a victim involved in it, I would be seeking ways to divert and dismiss. We have proof that people that have been tagged with conviction have a very difficult time getting jobs, going back home and supporting their family, and being productive members of their community. We also know data-wise that it doesn’t cause less recidivism, it doesn’t make a community safer to convict people of offenses like this. It doesn’t make sense from a public safety standpoint. It really undermines communities more than anything else to be seeking convictions for nonviolent misdemeanor offenses. It’s easier for me to tell you which ones I don’t think it applies to. You have to be very careful with things like assault, battery, and driving.

Could you walk me through how you’re thinking about diversion versus declination in these cases? For the offenses you listed, would you want to use a diversion program, or would you consider dropping the charges altogether?

I think a very important point: Prosecutors have enormous power. We can make a lot of decisions that are going to reduce the mass incarceration that we have right now. We can do dramatic things to attack the school to prison pipeline, which I think is a reality. But if you unilaterally make decisions that do not incorporate the other stakeholders and players in the legal justice system, you can get a backlash. Look at what’s happening in Norfolk, where the judges are rebelling against a unilateral “we aren’t going to prosecute marijuana charges.” That doesn’t help the defendant to do that. If you go in and null pross without having gotten some buy-in from the judges that you have to go in front of every day, you aren’t going to be able to accomplish what you’re setting to do, which is making sure that people don’t have convictions, and have a second chance. Instead, diversion is the easier project, because then you can give the judges something to hang their hat on.

I personally favor legalization of marijuana, that’s a legislative issue. In the meantime, for example, I’m envisioning a couple of things. In Fairfax, there is already a diversion program for shoplifting. You have diversion in the sense of a shoplifter’s awareness class, for first-offense, and that’s what Fairfax does, but I think it would be appropriate to go beyond that and look if there is a mental health issue underlying it, in which case mental health would be more appropriate, or whether there is an actual need component, in which case connecting to services would be a more appropriate way to manage. Prince William County’s practice has been that not only do you get convicted but you go to jail on a shoplifting case, and that’s flatly wrong. For possession of marijuana, instead of doing 251 dispositions we have now, which can’t be expunged, maybe you do something like just have a mental health or substance abuse evaluation, and the evaluation is enough, and a few days days later you just null pross the charge after the evaluation is done. We have those sort of resources in place that can be done now, and our judges, who I know very well, having appeared in front of them my entire career, would go along with it. I think you would achieve what you’re trying to achieve without backlash that you can’t control from your own bench.

Virginia’s incarceration rate is higher than the national average, so, more broadly, what role do you think prosecutors play a role in mass incarceration? To what extent would you make shrinking incarceration a goal if elected?

It would absolutely be a goal. Prince William County’s Detention Center right now has an evidence-based decision making board whose goal is to reduce the jail population by focusing the jail’s resources on people that are dangerous, for whom jail is the appropriate place to be. I’ve already participated in that. I’ve already been involved in an actual boots-on-the ground, how do we resolve this problem by reducing the jail population while not increasing the risk to the community. You don’t want to trade off actual public safety for reduction of the jail population.

There are ways that prosecutors actually hold the keys to this. That’s in the charging decisions, the plea recommendations, and the sentencing recommendations that prosecutors make. You obviously are familiar with all of the statistics that show that the decisions to become “tough on crime,” and I’m putting that in quotes, resulted in prosecutors who only ever see the conviction, lock-people-up. That whole culture has to change. If the culture changes, you make different decisions about the charges that you make. You don’t use charges as leverage in order to obtain convictions or guilty pleas. You don’t seek jail on charges for which mental health treatment is going to be more efficacious, or drug treatment is going to be more efficacious, or there’s not a true victim in the case and no reason that this person is going to be a risk to the community by being out of jail. Those decisions have really not been a component of the culture of prosecutors for a long time. But I don’t have those sensibilities, I’m a defense attorney at heart. My sensibilities have always been, how do we get people out of jail that don’t need to be in there?

We have limited resources, and we do have violent crime, and people need to be safe in their communities. Those are the things that you should be focused on: what does public safety require, not how I get more convictions. Diverting the majority of low-level offenses that are not violent and don’t impact public safety, it’s just a better use of our law enforcement resources than what we do right now.

The prosecutors hold it, we can make decisions about charging and about plea offers and about sentencing, tomorrow. We can institute those policies the day after I take office.

Many of the reforms you are proposing in this interview focus on changing the approach to low-level offenses. Research shows that significant cuts to mass incarceration will require changing our approach to higher-level offenses, and ones that involve violence. Are there also changes you would make with regards to the severity of charges or sentences sought?

I have a couple of thoughts about that. Violent crime has a component to it that lower level crime doesn’t, and that is that there’s an actual victim on the other side of it. And protecting victims is a fundamental job of the prosecuting attorney. You are now in an area where you have to be pulled in different directions. You absolutely have to protect people who are themselves the victims of crime. A goal should be to try to find cases and circumstances where restorative justice might be a path for certain kinds of crimes. You have to have the buy-in of the victim to do restorative justice; restorative justice is two people. It would be a good thing to set up a restorative justice program, make it entirely voluntarily for victims to get involved in, and see if you can build a restorative justice system.

The other thing I would say is, prosecutors can find cases where it’s appropriate to recommend something different than a guideline sentence. The legislature went and took 30 years of previous criminal convictions, and they created these formulas based on what had already happened. So the guidelines are premised on decades and decades of previous conviction data. This means that guidelines, which are the perceived norms, are built on a time where the country believed that high incarceration was the solution to things. You’re fighting this uphill battle in the criminal justice system of changing what the norms are because the guidelines, which are set up by the legislature, are built on a time when incarceration was the answer. One thing you could do differently as a prosecutor is offer a guilty plea but leave open the possibility that a defense attorney can argue for less, that they can argue for something other than a guideline sentence, in cases that you think the person deserves that second chance or deserves to have an advocate talk about why the guidelines are too high for them. We’re talking about crimes of violence, right, so the prosecutor’s job is going to be to advocate for the state, but you can absolutely leave open ways for defendants to have the opportunity to argue for something else.

The most damaging thing that prosecutors do in those sort of cases is foreclose the ability of their lawyers to make arguments for below guidelines. They’re harm-stringing you into a guilty plea. As prosecutors you have to be careful about that, and it’s not something you can do overnight. You’d have to change the culture around this, and always be mindful — we’re representing the state and we’re representing victims. Violent crimes are harder to make very rapid change to by the stroke of a pen.

Those are the two things. I would love to create a true restorative justice program, and find victims in crimes where they want to actively participate in that restorative justice. It can be much more healing, something useful for victims. And you can look at how you make recommendations for defense.

You have just talked about the inequity of the death penalty, or about overincarceration. You have also been endorsed by the incumbent commonwealth’s attorney. How do you think about that endorsement given that you are now describing reforming how the county approaches prosecution?

It’s not inconsistent. Paul Ebert didn’t endorse me because he thinks I’m going to carry on the policies of his office. I’ve been banging my head against that office for 25 years. What Ebert talked about, if you actually read his endorsement, what his endorsement says, is that I have deep convictions about the fairness and carrying out of the rule of law and the importance of honesty and integrity of law enforcement, and courage in doing the right thing regardless of popularity. Ebert knows, are you kidding me? I’ve been advocating like this my entire career. He knows what I believe in. He doesn’t endorse that I will continue his legacy, he says that I will have courage, and I’m going to do the right thing, and I’m going to be honest.

You said earlier that you had the sensibility of a defense attorney. What explains your decision to jump to the office of the prosecutor?

Exactly the reasons we’re talking about right here. Because prosecutors have enormous power to reform the justice system in ways that will bring equality and fairness to the system, in ways that don’t exist right now. A single defense attorney, day in and day out, representing one client at a time, is going to make enormous changes in the lives of their clients. But, if you really care about criminal justice reform, I can see a much better way to have much larger, and more broad, and more deep impact on our communities and on the individuals that get caught up in the criminal and legal system by being a prosecutor instead of a defense attorney. I want to make that change. I’ve been fighting for it my entire career, and now I have a chance to make real change as a prosecutor that understands criminal justice reform. I have been actually on that evidence-based decision-making board, and I have been the prisoner’s advocate for Georgetown University’s Institutional Review Board. This is a great way to make real criminal justice reform. Who better to do it than a trial lawyer that’s tried absolutely every kind of case, including a death penalty case, has actual thoughts about how to accomplish this stuff? I’ve done it. I mean, I’ve practiced in Fairfax, I’ve watched how their docket works with shoplifters. This is a great opportunity, finally, to make a significant change in the way Prince William handles equal justice issues and justice reform, while making the safe community that we have.

There is a sense that in the midst of all this incredible growth of opportunity in Prince William County—the county is a safe place to live for most people, the problem is that the justice system’s fairness and equality haven’t been shared equally by every part of our community. People are left out, communities of color especially, and that has to change. Secure communities have to be universal. Everybody has to be treated fairly and equally.

There have been instances in which the incumbent commonwealth’s attorney has been found to engage in misconduct, for instance in withholding exculpatory materials. What steps would you implement to make sure to avoid repeating this, and in particular to release all potentially exculpatory material?

We would do what I have advocated for 25 years, and what other jurisdictions do. We move to an open file system. The Supreme Court of Virginia is moving in this direction anyway, so it’s going to happen anyway. The commonwealth’s attorney should be at the leading end of this. There are issues for things like witnesses protection where there are legitimate concerns about some things being disclosed, but those are not insurmountable, in fact they are not that difficult to deal with. You just implement a policy of open file in most cases. That levels the playing field. It makes things fair. We’re still going to convict the people that need to be convicted, even if you open our files and show the defense what we have. You lay out guidelines for criteria that prosecutors have to follow, and if they don’t want to follow them they can go work somewhere else.

Can you define what exactly you mean by open file, or what exactly you understand by it?

Sure. In a simple case, you are going to have the charging documents, sometimes a criminal complaint, those are already part of the court’s files, so defendants can get that. The things that they can’t get, or traditionally don’t get, are things like the officer’s narratives of the event, what the officer typed in his file about his investigation, and you don’t typically get victim’s statements. Some jurisdictions give it to you, Prince William County generally does not. So you don’t know necessarily what the allegations against you are. Most of those things, in my opinion, again with some care about protecting potential at-risk witness, should be handed over to the defense. Make copies and give it to them. Don’t have the defense attorneys come in and sit down and have to write stuff down. Make a copy, hand it over.

The Appeal: Political Report has also interviewed Parisa Dehghni-Tafti (Arlington County), Steve Descano (Fairfax County), and Amy Ashworth (Prince William County).