New Hampshire Abolishes the Death Penalty

New Hampshire becomes the 21st state to abolish the death penalty.

Daniel Nichanian | May 30, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

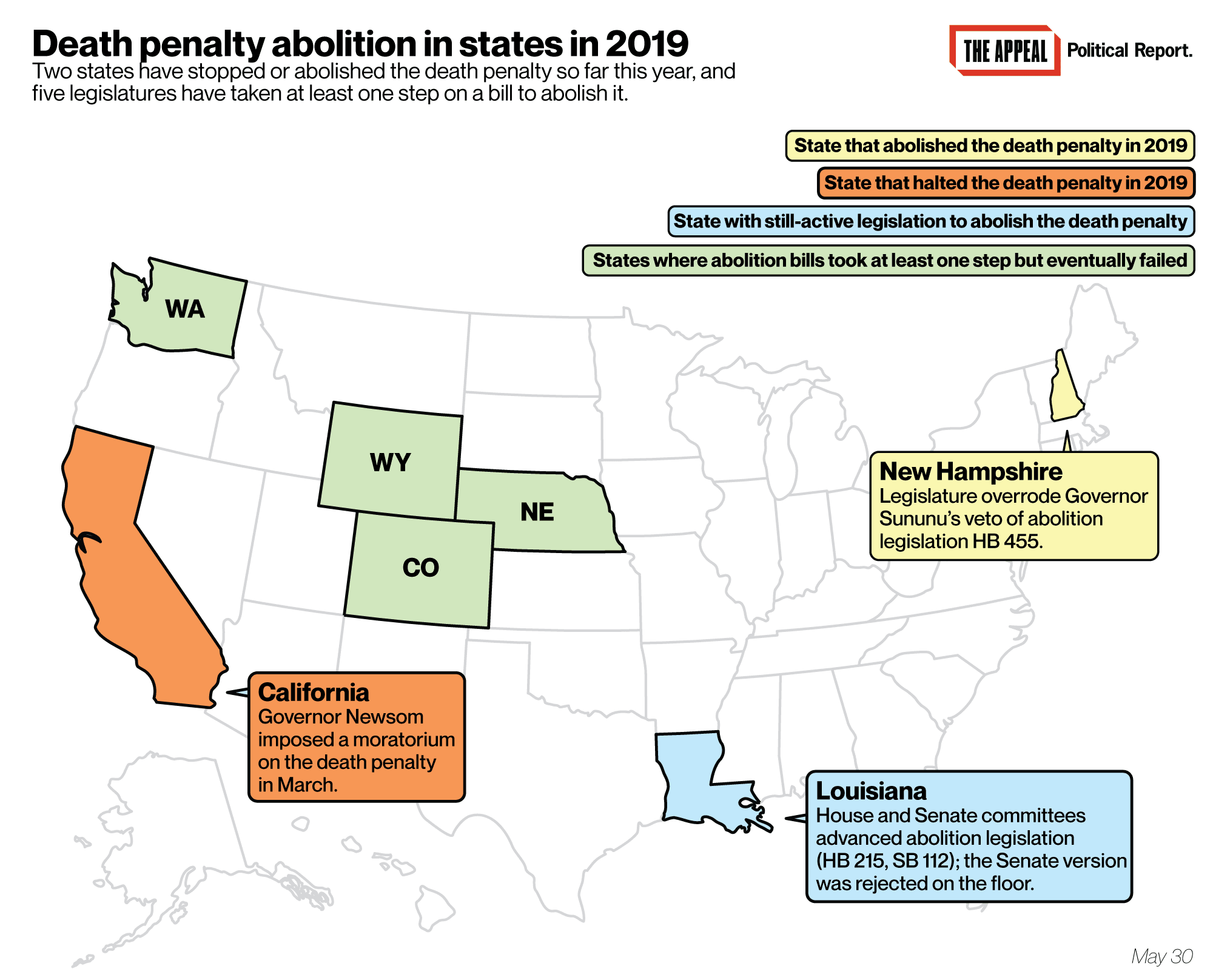

New Hampshire is the first state to repeal the death penalty this year. What is happening elsewhere?

New Hampshire abolished the death penalty Thursday. The Senate voted one week after the House to override Governor Chris Sununu’s veto.

The law passed the Senate with no vote to spare, but that was enough to make New Hampshire into the 21st state to have abolished the death penalty. That number that does not include states with governor-imposed moratoriums. Sentences and executions have also considerably declined nationwide.

“We’re experiencing a climate change in the United States when it comes to the death penalty,” Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, told me after the vote. “With New Hampshire’s abolition, half of the states have either abolished the death penalty or have a moratorium on executions. … The death penalty is disappearing from entire sections of the United States.”

Washington was the most recent state to repeal the death penalty when its Supreme Court struck it down in 2018. But no legislature had repealed it since Nebraska in 2015, and voters there reinstated it a year later. Abolition bills adopted by Connecticut, Illinois, and Maryland earlier this decade still stand. Also, Governor Gavin Newsom imposed a moratorium on the death penalty in California this year.

Although New Hampshire has not executed anyone for 70 years, abolition proponents say this law is significant. John-Michael Dumais, the campaign director of the NH Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, told me in the fall that success would help people around the country who argue that the death penalty “doesn’t conform to our evolving standards of decency.”

Achieving abolition can also free up the energy and imagination of reform advocates. New Hampshire will now have “space to look more broadly at the issue of criminal justice reform,” Dunham told me. “In states with the death penalty, when you address criminal justice reform, it’s hard to do so while ignoring the harshest punishment that’s available. By redressing that issue, you have the opportunity to address others as well.”

Case in point: In Massachusetts and Vermont, which have already repealed the death penalty, advocates this year have pushed for abolishing sentences of life without the possibility of parole. In death penalty states, life without parole sentences are discussed in the context of being an alternative to capital punishment. “When I talk about those, I have to talk about death penalty cases,” a reform-oriented candidate for prosecutor in Virginia told me last month when I asked him about life without parole sentences.

One immediate matter in New Hampshire is that its new law is not retroactive. It does not affect the sentence of the only person currently on death row, Michael Addison. Local observers say that state courts may commute the sentence.

Newsom’s moratorium in March prompted conversations about Democratic politicians’ growing comfort with opposing the death penalty. That was on display in New Hampshire. Democratic lawmakers were nearly unanimous in favor of abolition (218 of 224 voted yes in the chambers’ initial votes). Moreover, the Democratic surge in the 2018 elections is what gave abolition the veto-proof supermajorities it lacked last year.

But GOP lawmakers proved decisive as well. Nearly half backed abolition when legislators first sent the bill to the governor. While that share fell when it came time to override the Republican governor’s veto, the override would not have passed on Democratic votes alone. In the Senate, where the bill needed 16 votes, four Republicans joined 12 Democrats to override Sununu’s veto and get abolition across the finish line.

“I’m a pro-life advocate, and that is a credo I’ve tried to live with my entire life,” Republican Senator Bob Guida said on the floor shortly before voting for abolition. “We need to reinculcate a consideration of the All-Mighty as the arbiter of life.” Heather Beaudoin, a senior manager of Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty, told me after the vote that she was “excited to see so many Republicans jump on board, which is completely consistent with what we have seen across the country… We think it’s inconsistent to say that we are pro-life, but then say except people who have committed heinous crimes.”

Other abolition efforts have moved forward but fallen short so far this year.

Wyoming came remarkably close to repealing the death penalty. Abolition passed the largely GOP House but fell just short in the Senate. It also lacked sufficient support in Colorado and Nebraska. In Washington, the House did not take up an abolition bill adopted by the Senate by the end of the legislative session; it would have enshrined last year’s ruling striking down the death penalty in state law.

Legislatures also considered other sorts of legislation pertaining to the death penalty, but many legislatures adjourned over the past month without adopting these changes, effectively killing them until at least 2020. As a result:

Iowa will not reinstate the death penalty this year. A bill moved past a Senate committee, but the chamber’s leadership did not call it for a floor vote by the end of the session.

Missouri will remain one of three states, alongside Alabama and Indiana, that allows a death sentence even if a jury has not reached unanimity on sentencing. I flagged bills to change this in April, but both died at the end of the legislative session.

In Texas, a bill that would have established a pretrial hearing about intellectual disability had initial success and passed the House but it was considerably weakened in the Senate. The chambers did not reconcile their versions by the end of the session this week.

The most significant death penalty bill still standing this year may be Oregon’s House Bill 3268. The death penalty cannot be fully abolished via regular legislation in Oregon, but this bill would significantly shrink the category of crimes capital punishment covers.