“We Won’t Have People Stacked on Top of One Another in Prisons, in Cages”

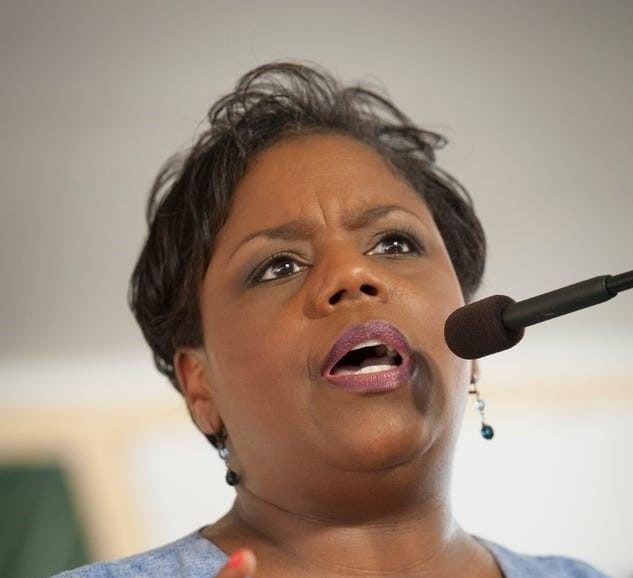

In a Q&A, Jennifer Riley Collins explains how she would fight overincarceration if she is elected as attorney general of Mississippi this November.

Daniel Nichanian | September 6, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

As executive director of the ACLU of Mississippi from 2013 through June, Jennifer Riley Collins worked to reform Mississippi’s criminal legal system. Now, she is running as the Democratic nominee to be the state’s next attorney general.

That office represents the state in court, among other duties. But Collins frames her bid as a continuation of her work as an advocate. “My interest has always been in protecting and defending the Constitution of the United States, protecting and defending the constitutional rights of all its citizens,” she told me. “If our Constitution and our laws say that a person has that right, I want to make sure that that right is evenly applied across the board.”

In a wide-ranging conversation, I asked Collins what this commitment looks like when it comes to issues that involve the criminal legal system, and what an attorney general could actually do.

Mississippi has one of the country’s highest incarceration rates. While DAs and law enforcement officers are generally independent of the attorney general’s office, Collins said she would focus on training them to detain fewer people, so as to free up resources for community services and treatment. “Being hard on crime is not the best approach, because we are throwing people away, we are impacting entire communities,” she said. “I think as I begin to set the standard for how we are going to approach criminal justice as Mississippi’s top cop, you will see the narrative begin to shift as well. … Doing the same thing that we have done, being hard on crime, has already proven not to work, so why do we continue to do that?”

“If we’re working with law enforcement who could have issued a person a summons instead of putting that person in jail, if we’re working with prosecutors,” she added, “then we’re dealing with the drivers of overincarceration, and we won’t have people stacked on top of one another in prisons, in cages.”

On issue upon issue, Collins made the case that inadequate funding for public services—be it teacher salaries, Medicaid expansion, mental health services, or jail conditions—is feeding overincarceration and creating collateral crises. “We need to make sure that our teachers are receiving a wage so they’re not having to work two or three jobs, so that they’re tired and end up trying to push zero-tolerance policies which drive children out of schools, and we know that everyday that they’re outside the learning environment is a day they are more likely to end up in the prison system,” she said. “All of those things connect, none of them are in isolation.”

Part of her approach, she added, would involve using the attorney general’s platform to publicize lawmakers’ budgetary decisions. “If we want to fix what’s going on in jails,” she said, “beat up on the people who are controlling the budget.”

We also discussed the terrible conditions in state prisons (she called them a “direct result of our reliance on overincarceration”), Mississippi’s restrictive disenfranchisement rules, and DA misconduct in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in the Curtis Flowers case.

If elected, Collins would become the first Black politician to hold statewide office in the state since Reconstruction, according to the Jackson Free Press. Mississippi is the state with the highest share of African Americans. It has a long history of voter suppression and intimidation, and Jim Crow-era laws are still weighing on the present campaign.

“I say it is time for us to take a seat that is already at the table so that we can inform laws and policies that are impacting everyone at the table, not a contingent of Mississippi,” she said, quoting Shirley Chisholm’s call for people to “bring a folding chair.”

Collins, who also served in the United States Army, retiring in 2017 as a colonel, secured the Democratic nomination to replace outgoing Attorney General Jim Hood in August. She will face off against Republican nominee Lynn Fitch, who is currently the state’s treasurer, in November.

The interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

You have worked for organizations, like the ACLU or the SPLC, that advocate for change, lobbying or suing the state. The attorney general can advocate for or demand change as well, but part of the job is to defend the state in court. How do you think about that transition, and about how you’ll balance advocacy for change and this role of defending state positions?

My interest does not change. My interest has always been in protecting and defending the Constitution of the United States, protecting and defending the constitutional rights of all its citizens. In my advocacy role, in my leadership role, let’s say on the other side of the law, it is making sure that marginalized Mississippians have been able to have their voice heard in court. When the state is making decisions that impact a person’s rights, a person who is indigent, they should not be penalized or receive unfair practices because they’re poor. Those are issues that I’ve advocated for. As the attorney general, I am duty bound to uphold the Constitution. If our Constitution and our laws, in our country and our state, says that a person has that right, I want to make sure that that right is evenly applied across the board.

I’d like to discuss a range of issues related to criminal justice reform, and what your powers would be as attorney general. First, the opioid crisis: It’s often treated as a law enforcement matter, and addressed with harsh criminal penalties, but you’ve said not enough is done for people to receive treatment. What do you think a system that treats addiction as a public health issue looks like, and what should be the role of the criminal legal system with regards to opioids?

People who are touched by the criminal legal system should be protected from the front end to the back end. If a person has a health disorder — let’s say a person has cancer or diabetes — do we throw them in jail because they have an illness? We don’t. If a person is suffering from an opioid or other illicit drug problem, that is a diagnosable health disorder. We shouldn’t be throwing those persons them in jail where they don’t receive treatment.

Everyone across the criminal legal system can play a role in that. As Mississippi’s next attorney general, I would like to play a role towards training law enforcement officers. When you’re charging a person with a crime that is related to a person’s drug addiction, are we dealing with the root cause of the behavior, or are we just dealing with a symptom of the greater issue that’s the substance abuse problem? Is it better to give a person a summons, or to put them in jail? If it’s simple drug possession, giving a person a summons and allowing them to come to work, versus locking a person up, has a dramatic effect not just on that person but also on their families.

As we talk about law enforcement, are we making smart decisions that impact not only the person, but the person’s family and the community in which they live? Because when we lock people up, who’s bearing the brunt of that cost? It’s the taxpayers, so we need to be able to balance that out.

The most powerful person in the legal system is the prosecutor, the district attorney, because the district attorney decides what cases are brought before the court and which cases are not. They make sentencing recommendations. So looking holistically, and making sure that we’re addressing biases in how we’re prosecuting. As the attorney general, I want to work with prosecutors to make sure that we’re not prosecuting in a biased manner, that we’re making (to borrow a phrase) smart justice initiatives. As Mississippi’s attorney general, I get the honor of training and working with prosecutors across the state and changing the narrative about how we’re impacting the communities.

In fact, the U.S. Supreme court put Mississippi prosecution under the spotlight in June when it struck down the conviction of a man, Curtis Flowers, because of the way in which Mississippi DA Doug Evans dismissed African Americans from the jury. The court’s opinion was circumscribed to this case. But how representative do you think this story is of the role of racial discrimination or racial inequality in how prosecution works in Mississippi?

Without factual data, I couldn’t say. I will say that there are some prosecutors who have been sitting in their seat unchallenged, just like the prosecutor in that matter, for term after term after term. And they came up in an era of war-on-drugs, hard-on-crime. But I think communities are rising up and challenging the status quo and saying, “This is not going to be the way we continue to allow our communities to be treated.” We see more young folks who have begun to run for office, and say we want to be representative of the entire community, because truly that is the only way the entire community is safe.

What we’ve learned is that being hard on crime is not the best approach, because we are throwing people away, we are impacting entire communities. We have to change the narrative. Again, the taxpayer is paying the brunt of the cost; families are paying the cost of these policies that just don’t make sense for Mississippi.

DAs are independent of the attorney general’s office. They are elected independently and make their own decisions regarding charging and prosecution. In light of that fact, what powers would you have as attorney general to improve DAs’ accountability and conduct? What initiatives are under the jurisdiction of the attorney general?

The attorney general’s office does work with district attorneys on training. We train district attorneys across the state. Yes, they are elected independently and responsible in their own jurisdiction. But I will tell you: Leadership leads from the front. I think as I begin to set the standard for how we are going to approach criminal justice as Mississippi’s top cop, you will see the narrative begin to shift as well. I think you will see other attorneys begin to follow that narrative because that is the narrative that makes sense for the citizens of Mississippi. Doing the same thing that we have done, being hard on crime, has already proven not to work, so why do we continue to do that?

When you say, “if you have served your time,” can you specify what stage you have in mind?

Emphasizing treatment, being trained so we don’t have biased policing and prosecution, making sure that we are being not only transparent but also accountable to the communities that we serve.

You mentioned the Curtis Flowers case: I will tell you, as Mississippi’s next attorney general, I will never defend discrimination. If a state actor is acting in a discriminatory manner, then that state actor needs to make an adjustment.

Doug Evans now has the authority to try Curtis Flowers yet again (which would be the eight time) but, as Mississippi Today reports, he can also request that the attorney general’s office take over the case or give it to someone else. Given Evans’s decades-long history in the case, as attorney general what would you recommend that he to do?

I would invite him to uphold the law. And as the Supreme Court has said, when he is moving in a discriminatory manner, making sure that African Americans are not included in the jury pool, he is breaking the law. Of course the decision is his in how he proceeds in his jurisdiction. But I would invite him to uphold the law.

A federal judge, Carlton Reeves, has ruled that Mississippi is not doing enough to keep people with mental health issues in community settings, and that the state must provide “access to a minimum bundle of community‐based services that can stop the cycle of hospitalization.” What is your reaction to this ruling’s characterization? If elected attorney general, would you appeal the ruling?

Judge Reeve’s characterization of Mississippi’s mental health services is accurate. We have not protected one of our most vulnerable, our citizens with mental illness. Protecting our most vulnerable is the hallmark of my life’s work and the touchstone of our campaign.

How would you work as attorney general to improve mental health services? Outgoing Attorney General Jim Hood long called for more mental health funding, though he then defended the state’s situation in court.

The state legislature appropriates funds for state agencies. One of the responsibilities of the Attorney General is to highlight when legislative action is not enough. In this case, the underfunding of mental health services. As attorney general I will inform both the legislature and the public when elected officials are not acting in the best interest of citizens. Our fellow citizens with mental health issues should be taken care of in their communities, not locked away.

One challenge to access to health care has been that the state has not expanded the Medicaid program. What is your view of the impact Medicaid expansion would have on Mississippi, and what would you recommend that the state do?

Mississippi is at the bottom of the pile when it comes to issues of need for access to quality health care. The citizens of the state of Mississippi are dying, literally, because they cannot access health care. I got in the race because I believe in protecting, defending, and serving, particularly those individuals who have not shared the same privileges I’ve had in life. And one of those privileges I have always had is health care. I think everyone deserves to have access to healh care, so of course I would support Medicaid expansion. I fully support as the Supreme Court has said that the ACA is constitutional, and that people deserve access to health care.

The state has not elected an African American to statewide office since Reconstruction, even though nearly forty percent of the population is black. What do you think is the effect of such a representation gap on the shape of politics and racial justice in the state today?

You’re informed by what you’re informed by, by your own life experiences, right? If leadership has not had the experiences of diverse communities when they have made laws and policies (focusing on how those laws and policies impact communities of color, marginalized communities, LGBT communities), those things have not been considered. Bringing diversity to the table, to take a seat that is already at the table, borrowing from Shirley Chisholm who said, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table bring a folding chair.” I say it is time for us to take a seat that is already at the table so that we can inform laws and policies that are impacting everyone at the table, not a contingent of Mississippi.

Perhaps related to this: The election will take place amid Mississippi’s exceptionally harsh disenfranchisement rules, and 10 percent of the state’s voting-age population is barred from voting. How do you think about the fact that you are seeking elected office in such circumstances? What do you advocate for the state to do on this issue?

My position on this has always been the same: If you have served your time, you have paid your fine, you have paid society back, you should be fully restored. We still tax you!

When you say, “when you’ve served your time,” can you specify what stage you have in mind?

When you’ve been convicted of one of the 22 disenfranchising crimes, whatever the sentence was, once you have met the terms of that sentence, you should be fully restored. I’m a Christian, I believe in redemption and restoration. So I think a person should be fully restored to their full rights of citizenship, and access to democracy coming through the vote is a right of citizenship.

The incumbent attorney general has filed lawsuits against prison contractors alleging corruption. Advocacy groups and incarcerated people have filed other lawsuits regarding the poor conditions in prisons; one prison is under a federal consent decree. How would you characterize the conditions inside the state’s carceral system, and how do you intend to use your office’s powers to confront them?

The conditions that are happening inside of Mississippi prisons are a direct result of overreliance on mass incarceration. You cannot put 20,000 people in jail daily, and expect the prison not to fill up and become a place where people are stacked on top of one another. And then, we’re not providing the resources to the department so those people are kept in a safe environment, in an environment where they can be rehabilitated so they can be fully restored.

You cannot look at this system, and what’s happening inside of the prisons, without looking at the drivers of why these people are there, and looking at how the Department of Corrections is being resourced. The responsibility of the Department of Corrections does not lie solely with the commissioner. The issues that are going on with the Department of Corrections also lie with our state legislature and our state leadership, which has been supermajority controlled. If we want to fix what’s going on in jails, don’t beat up on the commissioner, beat up on the people who are controlling the budget.

We have to address front-end issues. Are we putting people in jail for nonviolent offenses that shouldn’t be in jail? If we’re working with law enforcement who could have issued a person a summons instead of putting that person in jail, if we’re working with prosecutors, then we are dealing with the drivers of overincarceration, and we won’t have people stacked on top of one another in prisons, in cages. We have to still treat people, even those people in prisons, even people who break the law, like they’re still human beings.

You have worked in your career on issues involving youth justice and minors’ involvement with the criminal legal system. You also just talked about addressing overincarceration. What do you think that should look like with regards to how we treat young people and kids.

We cannot talk about juvenile justice separate and apart from how we deal with education in the state of Mississippi. Our standard has to be greater than adequate, and that is the standard right now for education in the state of Mississippi. We have to ensure that our children receive quality education, and that our education system is not a school-to-prison pipeline.

It’s a funding issue, it’s also how we are paying our teachers: Teachers in the state of Mississippi are still at the bottom of the scale when you compare to teachers across the southeastern region. We need to make sure that our teachers are receiving a wage so they’re not having to work two or three jobs, so that they’re tired and end up trying to push zero tolerance policies which drive children out of schools, and we know that everyday that they’re outside the learning environment is a day they are more likely to end up in the prison system. All of those things connect, none of them are in isolation.