California Legislature Adopts a Flurry of Criminal Justice Reforms

New laws signed by Governor Newsom target private prisons, and fines and fees, the power of DAs, and more.

Daniel Nichanian | September 18, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Now on Governor Gavin Newsom’s desk, these bills target private prisons, and fines and fees, DAs’ power, and more. Voting rights have to wait until 2020, however.

Before adjourning for the year on Friday, the California legislature passed a series of bills reforming the state’s criminal legal system and its law enforcement and detention practices.

These bills are now all on Governor Gavin Newsom’s desk. Newsom has until Oct. 13 to sign them, veto them, or let them become law by doing nothing.

Here is a preliminary overview of eight of these bills.

1. Rights restoration: “It’s time to allow people with felony convictions to serve on juries,” Vaidya Gullapalli wrote in The Appeal in July. California is currently one of 27 states to permanently bar people with felony convictions from serving on a jury. This could soon end: Senate Bill 310 would allow most people with felony convictions to serve on juries after the completion of their sentence. The bill would not apply to people who are required to register on sex offender registries, however. The Appeal has reported on problems with California’s expansive registry law.

2. Sentencing (1): California is notorious for automatically expanding prison terms. SB 136 would eliminate one such mechanism: one year-additions to a person’s sentence for each prior felony conviction punished with prison or jail. Proponents of SB 136 organized an exhibit called “What a Difference a Year Makes;” it may seem obvious that it does, but as Vermont prosecutor Sarah Fair George told the Political Report in August, we too often treat prison time as an abstraction, “just throwing out numbers.”

3. Sentencing (2): Assembly Bill 484 would eliminate the requirement that individuals convicted of distributing some drug offenses receive a sentence that includes an at least 180-day jail stay.

4. Private facilities and immigration detention: AB 32 would ban private prisons and immigration detention centers; it was amended to include the caveat that the state can extend its contract with a private contractor if that is purportedly needed to alleviate overcrowding in state-run prisons. The bill should significantly cut ICE’s detention capacity in the state. It would not terminate the existing contracts of the four privately-run immigration detention centers in the state, which have capacity to detain 4,500 immigrants, but the contracts could not be extended.

Grisel Ruiz, an attorney with the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, an organization that advocated for the bill, frames AB 32 as a step toward ending ICE detentions in California. “Due process can’t coexist with detention,” she told the Political Report, noting that there is now only one publicly-run detention center (Yuba County). The San Francisco Chronicle reported in May that ICE was looking for more detention space in California, and that with local governments choosing to end their contracts, the federal agency struck new partnerships with GEO Group, a private company. GEO Group lobbied against AB 32. Ruiz acknowledged some advocates’ concerns that ICE detainees may be transferred elsewhere, but argued that bed capacity matters. “If you build it, they will fill it,” she said. “It makes ICE’s job to engage in enforcement much harder if they don’t have those immediate beds in their backyard.”

5. DA power: In her resistance to reform this year, San Diego DA Summer Stephan went so far as to ask some defendants to waive their hypothetical future rights to seek relief under still-nonexistent reforms. Lawmakers replied with AB 1618: If signed, it would void any deals where defendants forfeit rights derived from future reforms.

6. Fines and fees: Criminal fines and fees are a significant burden on poor people, and AB 927 would require courts to determine defendants’ ability to pay before imposing a financial obligation on them (except restitution); the bill also lists circumstances under which defendants are presumed unable to pay. Sponsors connect AB 927 to a recent court ruling that held that financial obligations are unconstitutional if imposed on people who cannot pay them.

That said, the legislature did not pass another bill (SB 144) that proposed outright eliminating many of California’s fees. The bill may return next year, and some local jurisdictions are stepping in for now. This week, the Contra Costa County Board of Supervisors voted to suspend criminal court fees imposed in the county.

7. Surveillance: AB 1215 would ban the use of facial recognition technology in police body cameras over the next three years, a temporary response to worries about surveillance.

8. Expungement: Most people eligible for the cumbersome process of expungement do not apply, so two states have adopted “Clean Slate” laws to automate it. California could be third: AB 1076 creates an automatic expungement process for all misdemeanors and some felonies. “By removing the burden from being on the individual to request a record change (often requiring the services of an attorney), we reduce barriers to success by making the process less bureaucratic and more effective,” Jay Jordan, executive director of Californians for Safety and Justice, told the Political Report via email. Expungement “allows people to access jobs, housing, and other opportunities.” Outstanding fines and fees will not be a barrier.

However, the bill was amended to only apply to offenses committed after 2021. Jordan attributed this to budgetary limits and vowed to press ahead. The bill “establishes a pioneering foundation that can be built upon through future budget allocations to make it retroactive,” he said. “There is no longer a debate on whether providing relief to this broad group of people is sound policy, and that’s a pivotal turning point.”

—

The legislature also adopted other bills on matters like early release or health care in prison.

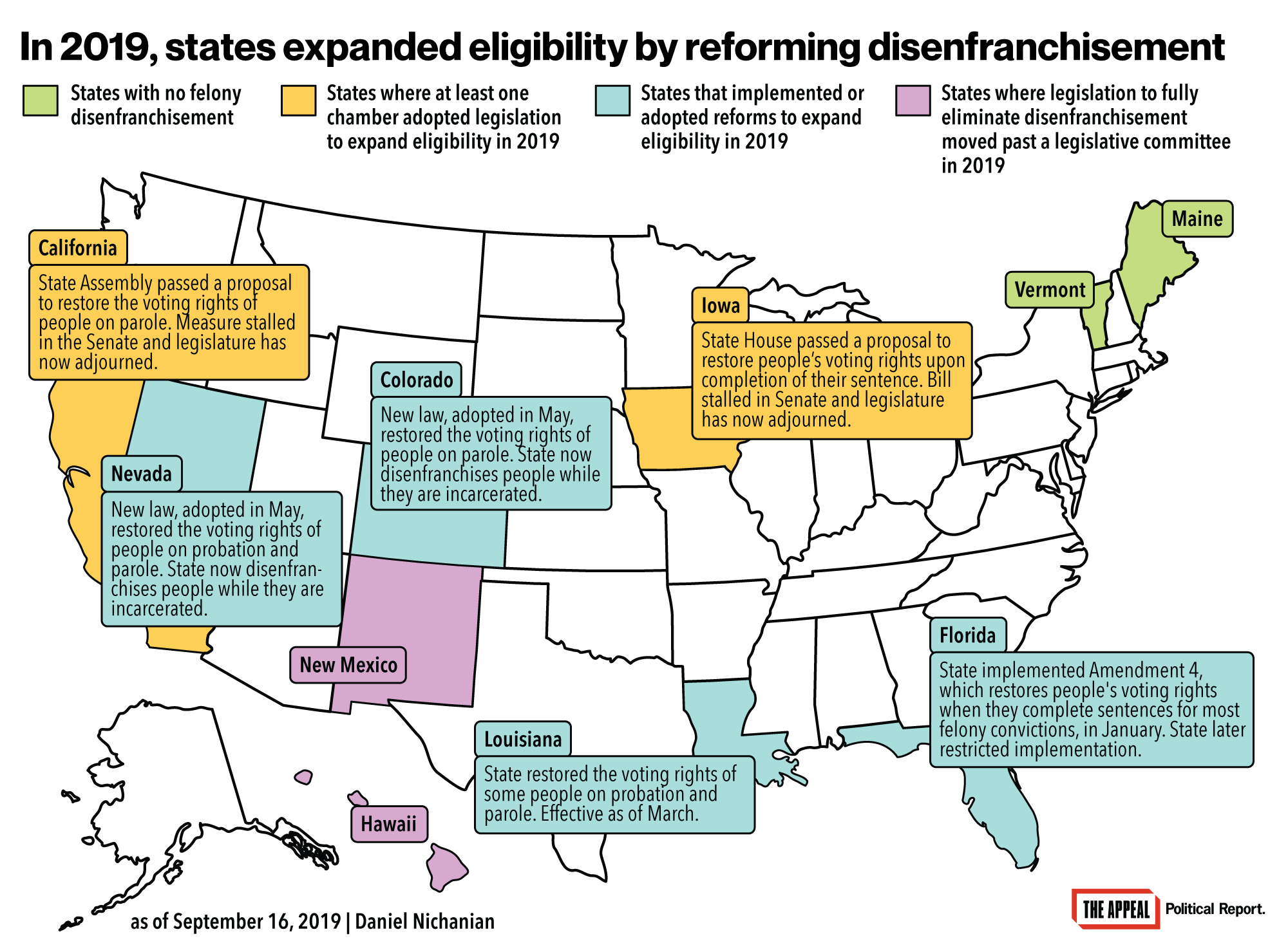

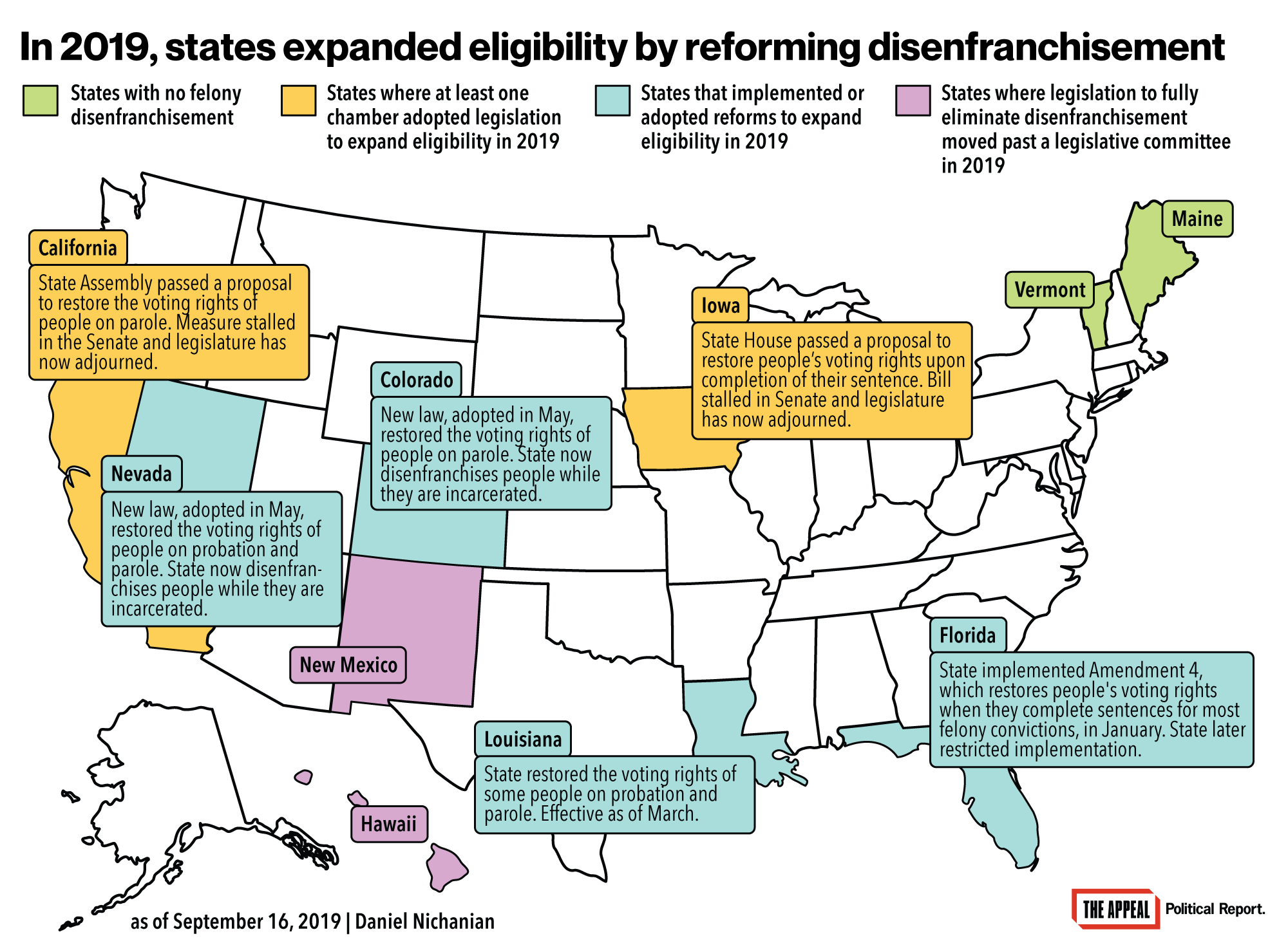

One measure that remained on the table is the constitutional amendment to restore voting rights for people on parole. The Assembly had passed it, but the Senate adjourned without voting on it.

Since California’s legislative process carries over into 2020, the Senate can adopt it after recess in January. That would place it on the 2020 ballot for voters to approve. Taina Vargas-Edmond, the executive director of Initiate Justice, a group that champions ending disenfranchisement, told the Political Report that she was “fairly optimistic” that the Senate would pass it next year. “I was pleasantly surprised by some of the debate on the Assembly floor,” she said. “We are going to continue working hard to raise awareness of the issue.”

California is one of 32 states to disenfranchise at least some people who are not presently incarcerated. (This is more restrictive than states with a more conservative reputation, such as Indiana or Utah.) This issue has seen significant legislative and political movement throughout this year.

—

Many of the laws that govern the American criminal justice system are set at the state level. Explore the latest developments on criminal justice reform in state legislatures around the country with the Political Report’s interactive tool on legislative reform.