Prosecutors Roll Out Reforms in Four States

A Maryland prosecutor stops seeking cash bail, Kentucky and Virginia prosecutors limit pot cases, and a Hawaii prosecutor reduces charges for driving offenses.

Daniel Nichanian | September 18, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

In Kentucky and Virginia, prosecutors limit marijuana prosecutions

A growing number of prosecutors are limiting or ending the prosecution of marijuana possession. The latest to join this trend are in Alexandria, Virginia, and Louisville, Kentucky.

Bryan Porter, the commonwealth’s attorney of Alexandria (a city of about 150,000in Northern Virginia), has announced that people charged with simple marijuana possession will be eligible for pretrial diversion. Their case would be dismissed after up to nine months of supervision and drug screening. This policy goes beyond state statutes, which only provide diversion for people’s first offense. It will help people “avoid the consequences of a criminal record for marijuana possession,” Porter told me. It has no restrictions regarding prior criminal history, he said, nor regarding the amount of marijuana possessed—as long as his staff does not consider possession to indicate an “intent to distribute.”

I asked Porter why he is not adopting a policy of just declining to prosecute marijuana cases, as others have. After all, this program remains burdensome for defendants and for law enforcement. He pointed to a state Supreme Court’s ruling in May that denied the Norfolk prosecutor’s power to dismiss marijuana cases filed by local law enforcement if judges were refusing to. Porter said his policy is on safer ground because he is using “the authority that I do have with regard to the disposition of cases.” That said, he acknowledges that even under his plan judges would need to grant the motions to dismiss the charges of people who have gone through the program. The question remains, therefore, whether local judges are sympathetic to reform. “My understanding is that the judges will honor our dismissal motions,” Porter said. “I do not anticipate any problems.” He also called on the legislature to decriminalize the possession of marijuana.

In Jefferson County, Kentucky (home to Louisville), County Attorney Mike O’Connell rolled out a policy of no longer prosecuting people for possessing up to one ounce of marijuana. It applies to cases where marijuana possession is the only or most severe charge. O’Connell pointed to the racial inequality in marijuana prosecutions. “For me to truly be a minister of justice, I cannot sit idly by when communities of color are treated differently,” he said. In January, a Louisville Courier Journal investigation found that African Americans are far likelier than the city’s white residents to be charged with marijuana possession, despite comparable rates of use.

As county attorney, O’Connell has jurisdiction over lower-level offense. (More severe charges fall under the jurisdiction of the commonwealth’s attorneys.) This covers the possession of up to eight ounces of pot. I asked his office why it continues to prosecute people who possess between one and eight ounces, rather than decriminalizing altogether. “With marijuana still fully illegal in Kentucky, we felt this was the most appropriate step at this time,” said a spokesperson. O’Connell’s decision has sparked discussion elsewhere in the state.

Maryland prosecutor will no longer request cash bail

Aisha Braveboy, the state’s attorney of Prince George’s County, announced a significant bail reform in a speech this month. “I do not believe in the cash bail system,” she said. “Starting October 1st, my office will no longer request cash bail as a condition of release.”

Reform advocates express optimism about the reform in the Washington Post. They also note implementation will be crucial. Reducing pretrial detention will depend on the judges who actually set bond, and who could deny people pretrial release. Also, what replaces cash bail will matter greatly.

One cause for caution is that Braveboy’s office told the Post that prosecutors could seek alternative conditions for release such as drug testing or electronic monitoring. These are burdensome, and could carry costs if defendants choose private monitoring or “less demanding” oversight, the Post reports. Denise Roberts, the communications director of the state’s attorney’s office, told me that prosecutors would seek release on personal recognizance, with no additional conditions, if they judge that a defendant “does not pose a danger” and that “there is no risk of failure to appear.” In addition, prosecutors could seek to deny bond to defendants whom they deem to be dangerous. Roberts said there should be no cases where prosecutors would have previously sought cash bail but would now seek to deny any release.

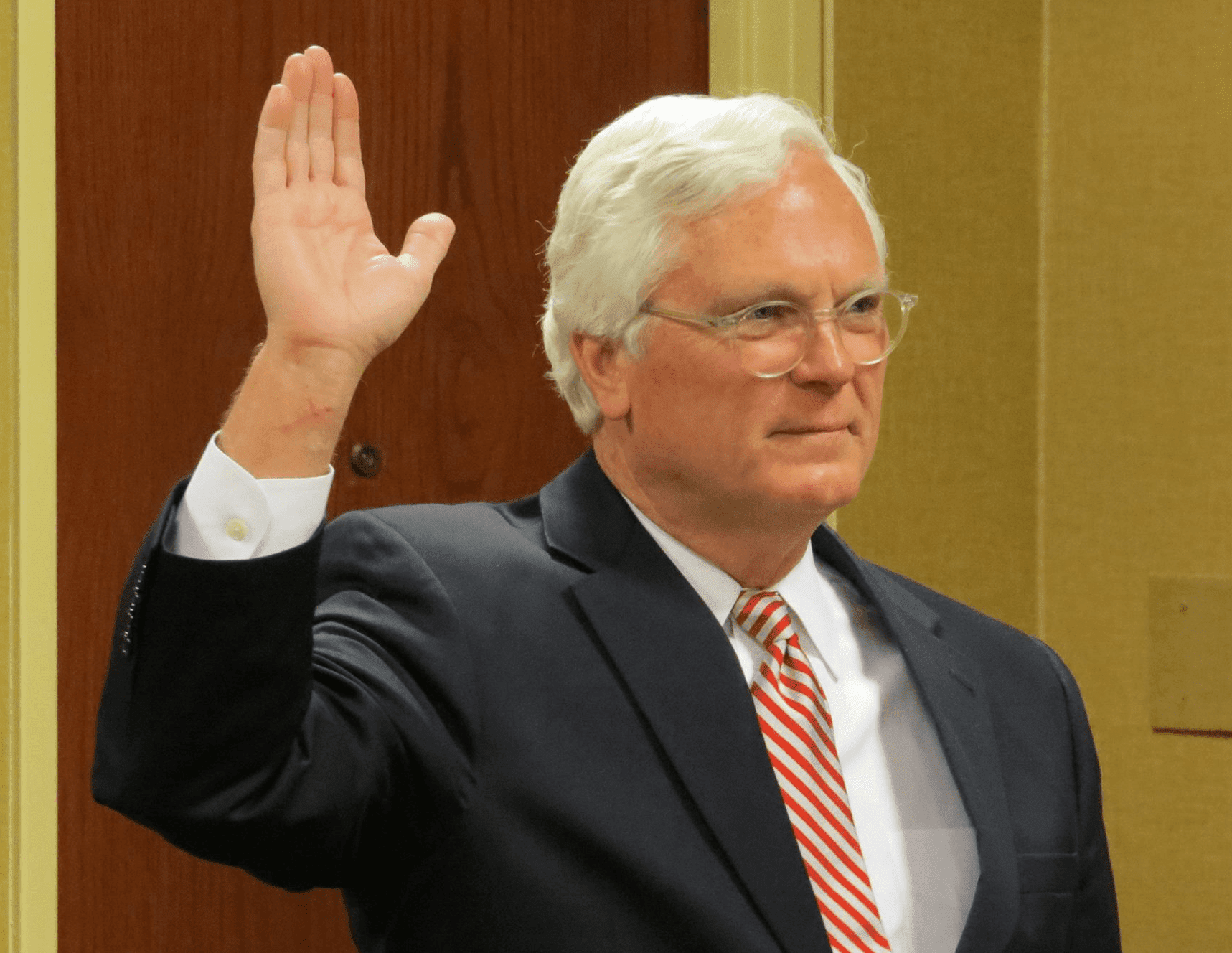

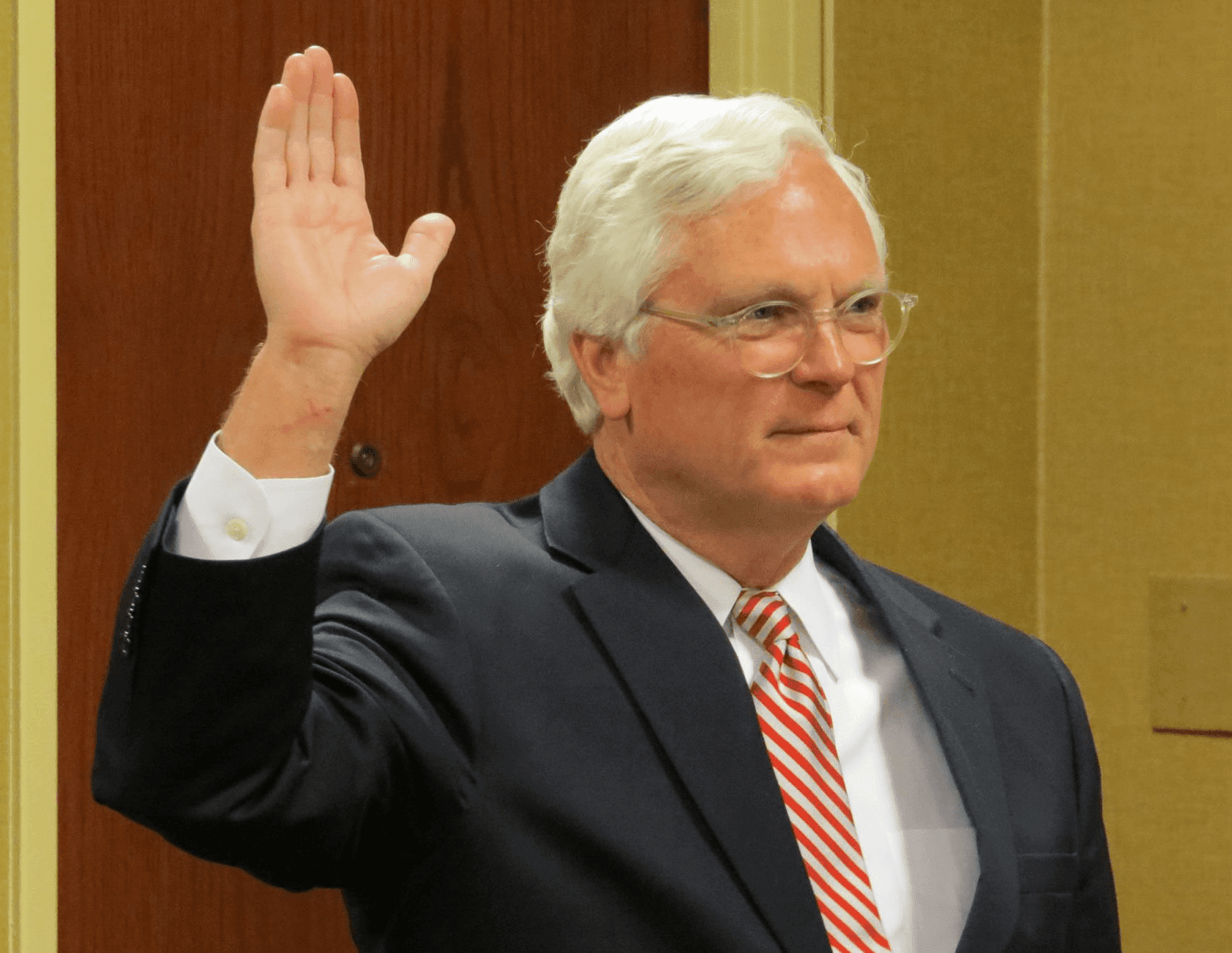

Hawaii prosecutor reduces charges for driving offenses

Justin Kollar, the chief prosecutor of Kauai County, rolled out a new policy to lessen penalties for driving without a license or insurance. These offenses are often linked to poverty and an inability to pay court debt, which triggers license suspensions. Hawaii law provides for harsher penalties and detention when a traffic infraction is treated as a repeat violation. Such enhancements “disproportionately impact the economically disadvantaged,” Kollar said, trapping them in a “cycle they can’t get out of.” So his office will treat all such infractions as first-time violations, regardless of prior history.

Hawaii’s other three chief prosecutors oppose Kollar’s move. They have a history of opposing criminal justice reform.

Elsewhere in the country, DAs like Rachael Rollins in Boston and Amy Weirich in Memphis have gone a step further: They have said they are altogether declining to prosecute cases of driving on a suspended license when the suspension is due to unpaid debt.

I asked Kollar why he is not adopting such a policy. He replied that his office only has access to limited information regarding “what caused the original suspension or revocation,” and that he cannot “see if the suspension or revocation was strictly due to fines.” He added that he would consider dismissing cases if the state provided such data, and that he would support legislation to end the suspension of driver’s licenses over unpaid fines.