Reform Candidates Face Pushback in Virginia

In Fairfax and Chesterfield counties, candidates for prosecutor want to reduce the volume of felony convictions. Reform opponents have coalesced against them.

Daniel Nichanian | October 17, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

In Fairfax and Chesterfield counties, candidates for commonwealth’s attorney want to reduce the volume of felony convictions. Criminal justice reform foes have coalesced against them.

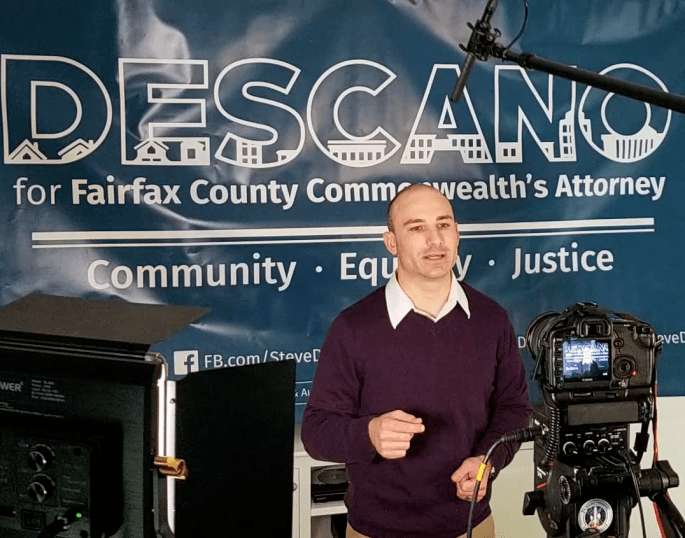

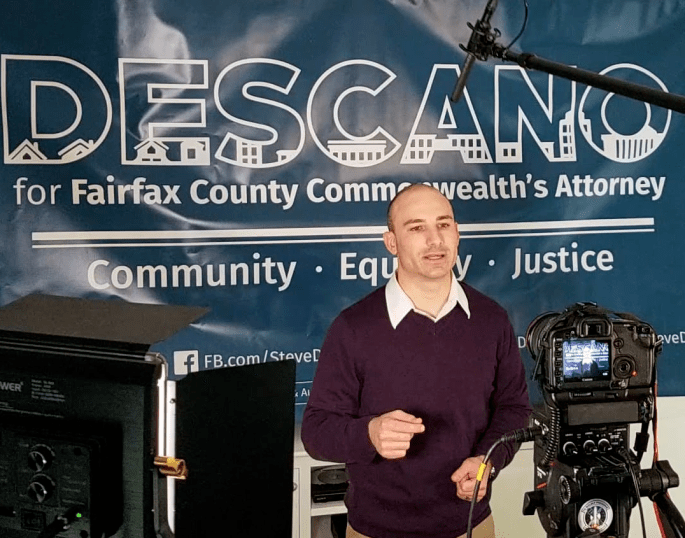

In the June Democratic primary in Fairfax County, Virginia’s largest jurisdiction, Steve Descano achieved what seemed like the hardest lift for his prosecutorial candidacy. Running on a platform of ending mass incarceration, he ousted incumbent Commonwealth’s Attorney Ray Morrogh. Since Fairfax County leans Democratic, and Republicans had no candidate anyway, Descano looked to be the favorite to win the prosecutor’s office on Nov. 5 and roll out his proposed reforms.

But Morrogh has since joined the local Republican Party and police unions in endorsing Jonathan Fahey, an independent who jump-started his campaign against Descano in August. Fahey is a former federal prosecutor like Descano, but unlike his opponent he is running on defending the integrity of the existing criminal legal process. He calls it a “great system.” And he says electing Descano would make Fairfax “go down the road of Philadelphia.”

Further south, in Chesterfield County, Scott Miles won a special election in 2018 to complete the term of a retiring incumbent. He proceeded this year to scale back the aggressive prosecution of lower-level offenses.

He, too, has faced concerted pushback from local players such as police unions that are skeptical of prosecutorial reform. Miles, a Democrat, now faces Republican challenger Stacey Davenport, who faults his reforms for ignoring crime and for going beyond a prosecutor’s role.

A defining issue in both elections is whether a prosecutor’s office should aim to reduce the volume of felony convictions, whether by steering more defendants toward programs that circumvent guilty verdicts, declining cases, or seeking convictions on lower-level charges.

A recent report by Justice Forward Virginia, a nonpartisan political action committee, documents great variation between Virginia counties as to the share of arrests over serious offenses that result in a conviction at the severe felony level. For Justice Forward Virginia, these disparities highlight some prosecutors’ greater tendency to overcharge, and thus their discretion to impact the volume of felony convictions and severity of sentences. Brad Haywood, the group’s executive director who is also Arlington County’s chief public defender, told me in an email that prosecutors who “produce higher rates of felony prosecutions and felony convictions” are fueling “over-incarceration.”

Haywood called on prosecutors to create “diversion programs that might be able to rescue us from this mess: programs that help defendants charged with non-violent offenses avoid criminal convictions (or felony convictions), and that prioritize treatment for defendants suffering from mental illness and substance use disorders.”

Miles has rolled out some such diversionary policies in Chesterfield County, but his challenger wants to discontinue them. Descano, in Fairfax, has proposed doing the same if elected. “I want to keep people away from felony charges whenever possible,” he told me in April. “There is a cycle of decreased opportunity, increased poverty, increased crime. That’s what we want to break here.”

Elsewhere in the state, other candidates echo such proposals. Jim Hingeley, running in Albemarle County, told me that he would make more frequent use of misdemeanor-level charges to decrease incarceration and to “make it more likely that a person could stay in the community.” Hingeley, alongside Descano, Miles, and others like Parisa Deghani-Tafti in Arlington County, could produce a possible wave of reform prosecutors in Virginia’s Nov. 5 elections. If elected together, most have said they would use their relationships to influence legislative changes.

Independently, they would still have authority to shape practices in their own jurisdictions.

Chesterfield County

Miles, who won in 2018 on a promise to lower the severity of drug charges, issued a directive to his staff soon after entering office to avoid seeking jail time for those found guilty of marijuana possession. Then, over the summer, he launched a diversion program in which defendants with felony-level drug possession charges (e.g. for heroin, cocaine, or oxycodone) are given the opportunity to complete a series of treatment steps in exchange for having charges dropped. The program is operating at a small pilot scale, but Miles has said its upshot would be to process more cases than the existing drug court permits.

This program does not require that people plead guilty before accessing the lower penalties that it unlocks, though it still holds the threat of criminal charges over people’s heads. Miles told the Chesterfield Observer that, before his tenure, office policy “was to obtain the felony conviction in almost every case.” Indeed, Justice Forward Virginia’s study shows that Chesterfield County prosecutors sought and obtained felony-level convictions more frequently than most of the state’s largest jurisdictions as of 2017.

Miles also implemented other policies to forgo criminal charges, though access to those alternatives sometimes implicates a financial cost like a $60 shoplifting prevention class, Richmond Magazine reported. Miles did not respond to questions on his policies.

Law enforcement figures have pushed back against his policies on behalf of more punitive practices. Kevin Carroll, president of the county and state Fraternal Order of Police, invoked a slippery slope of lawlessness last year in response to Miles’s marijuana policies. “When we start down this road, what’s the next thing we don’t charge on?” he told the Chesterfield Observer.

Davenport, Miles’s challenger who currently works as a prosecutor in a neighboring county, uses similar language. Of proposals to not prosecute pot possession, she said, “I feel like if you’re just continuing to ignore it or give people a slap on the wrist over and over and over again, you’re ignoring a problem. The constant use of marijuana is a problem and does lead to other drugs.”

She also told the Chesterfield Observer that she would discontinue Miles’s initiative to avoid felony-level drug possession convictions. She faults him for refusing to “prosecute as the law is written because of your personal feelings,” and for using the office to “pursue his political agenda.” A commitment to “prosecute as the law is written” is vague, however, given the vast discretion prosecutors enjoy and given counties’ varying practices and outcomes. Davenport did not reply to repeated requests for comment on her views.

In a September statement, Miles notes that he campaigned on the policies he has pursued during the 2018 election. “I did so in response to community observations that our court system’s decades-long approach of felonizing and incarcerating those engaging in self-harm has served us poorly,” he wrote. “This office is an elected one so that the person occupying it will perform consistently with contemporary community values.” Nov. 5 is indeed likely to determine the fate of his reforms.

Fairfax County and Fairfax City

Descano, a former federal prosecutor, has also made the case that prosecutors file excessively severe charges. He told me in April that he wants diversion programs that do not require defendants to first plead guilty, so that if they complete them they do “not have that record that follows them around” — records that make future incarceration likelier. He also said he would “create a presumption that any theft under $1,500 is treated as a misdemeanor.” (Virginia’s felony threshold is $500, low by national standards.)

His opponent Fahey, by contrast, denies that the criminal legal system needs much reform.

He has called Descano’s proposals “radical” and opposed his emblematic commitments of not prosecuting marijuana possession and not seeking the death penalty. In one radio interview, he attacked those who say that “the criminal justice system is inherently flawed and unfair and needs to be fundamentally changed.” He described it instead as “a great system we should be proud of and always work to keep improving.”

Fahey did not respond to repeated requests for comment over what improvements he would like to see, and for his views on decreasing the volume of felony convictions.

Fahey’s case against reform has earned him the GOP’s backing and the endorsements of the two Democratic prosecutors who lost to decarceral challengers in the June primaries: Morrogh, who lost to Descano, and Theo Stamos, who lost to Dehghani-Tafti in Arlington County. Morrogh and Stamos have histories of fighting reforms proposed by others in their party. In 2016, both joined a lawsuit against then-Governor Terry McAuliffe’s executive order to restore voting rights; in 2014, Morrogh testified in front of the U.S. Congress against the Obama administration’s proposals to reduce prison sentences.

Stamos said in 2018 that “mass incarceration” is a term “used to delegitimize what we do,” and Fahey echoed that language on a radio show this fall when he argued that “the agenda for these George Soros candidates is essentially to delegitimize the entire process.” A political action committee funded by Soros provided Descano significant financial support before the June primary; Fahey has raised more than twice as much money as Descano since July 1, according to campaign finance statements filed by both candidates as of Oct. 15.

Descano, meanwhile, has rolled out endorsements of his own from state prosecutors who have launched reforms, such as Portsmouth’s Stephanie Morales, who is now declining to charge people for marijuana possession. Nov. 5 will decide whether the ranks of those reformers grow.