Virginia Becomes the First Southern State to Abolish the Death Penalty

Abolition advocates are celebrating a milestone for racial justice.

Elizabeth Weill-Greenberg | March 24, 2021

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Abolition advocates are celebrating a milestone for racial justice.

Virginia, the state that has executed more people than any other in the nation, has abolished the death penalty.

The legislation abolishing the death penalty, which passed the House and Senate in February, was signed this afternoon by Governor Ralph Northam. “It is the moral thing to do,” he said during the signing ceremony. “The death penalty is fundamentally flawed.” Virginia becomes the first formerly Confederate state to abolish capital punishment.

“That’s a really clear and powerful denunciation of the death penalty,” said Cassandra Stubbs, director of the Capital Punishment Project at the American Civil Liberties Union.

Virginia has executed more than 1,300 people since its founding as a colony in the 1600s. It executed 113 of those people in the years since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated capital punishment in 1976, according to the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC). Only Texas has executed more people in the last 45 years.

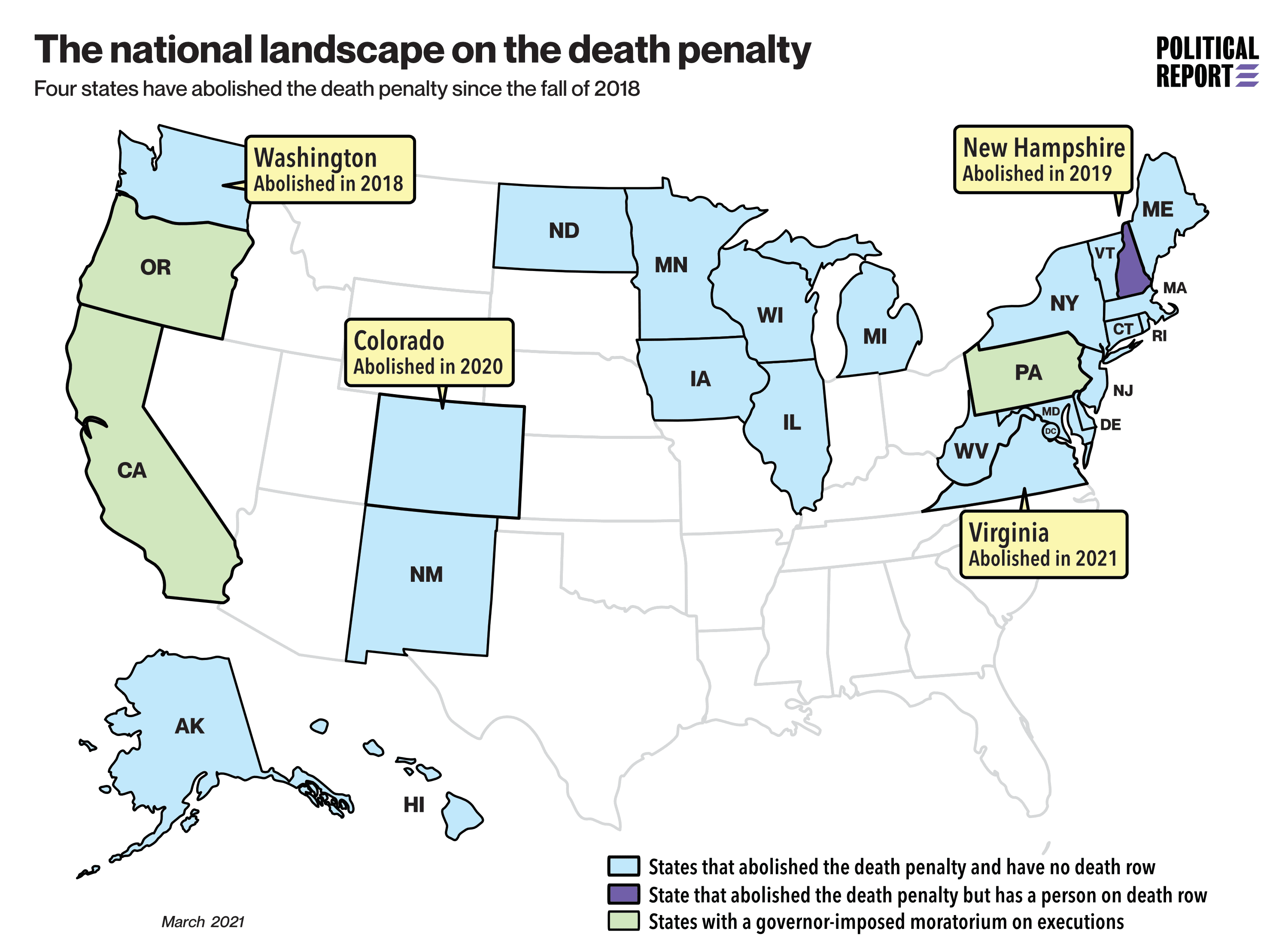

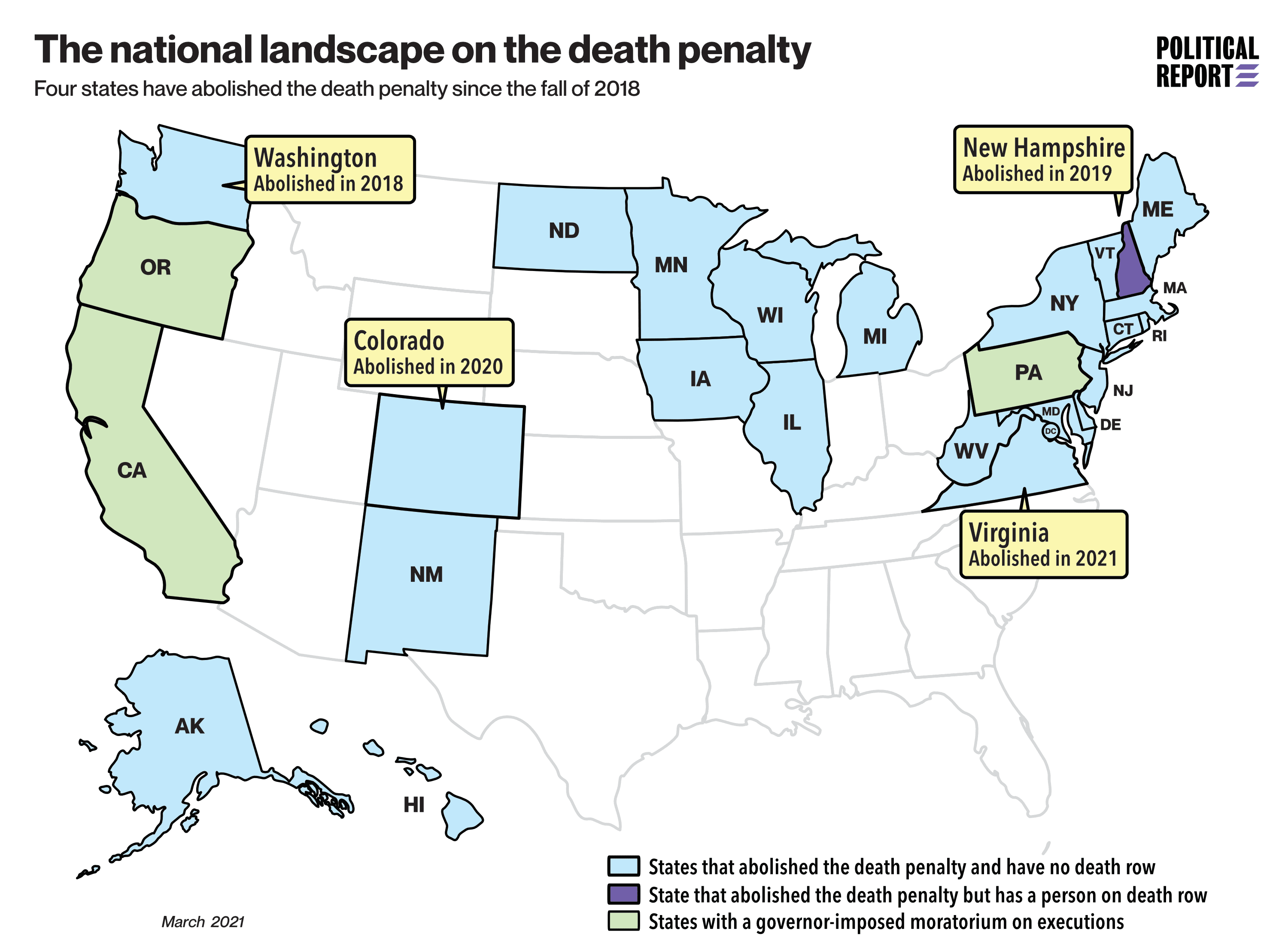

But the death penalty, both in use and popularity, has steadily declined in Virginia and throughout the country. In addition to the 22 states that had already abolished capital punishment, another 12 have not carried out an execution in at least 10 years, according to DPIC. In Virginia, a death sentence has not been handed down since 2011.

There are only two people on death row in Virginia, Anthony Juniper and Thomas Porter. Under the new legislation, their sentences will be changed to life in prison. Because they were 18 or older at the time of their offenses, they will not be eligible for parole or conditional release.

Even those who once defended executions have embraced abolition. State Senate Majority Leader Richard Saslaw, a Democrat, was among the 21 senators who voted to abolish the death penalty. But throughout his career, he had supported capital punishment, and in 2016 he joined then Governor Terry McAuliffe in protecting pharmacies that supply lethal injection drugs.

“There’s only two people on death row; juries are just not handing out the sentences anymore,” said Saslaw about his vote, the Washington Post reported. “That option’s not there right now.”

McAuliffe, who is running for governor again, announced his support for abolition in December. As governor, although he said he personally opposed the death penalty, he oversaw three executions during his tenure, including that of William Morva, the last person to be executed in Virginia. Rachel Sutphin, a daughter of one of Morva’s victims, asked McAuliffe to stop the execution, but he ignored the request.

In January, Sutphin and about 20 other family members of murder victims released an open letter to members of the Virginia General Assembly, calling on lawmakers to abolish capital punishment. Among the signatories were three state legislators who lost loved ones to murder, including Senator Janet Howell. Howell supported the death penalty until her father-in-law was killed.

“I don’t buy the idea that we would support the death penalty for the benefit of victims’ families,” Howell told legislators last month, the Associated Press reported. “It doesn’t work that way. Trust me, it doesn’t work that way.”

—

Capital punishment in Virginia, and throughout the country, is entrenched in white supremacy; its origins reach back to slavery, the Confederacy, and lynchings. Its demise in the formerly Confederate state was precipitated by last year’s Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

“It’s a major step in the right direction because this is a very biased judicial system, especially here in Virginia, the birthplace of racism, the birthplace of Confederacy,” said JaPharii Jones, president of Black Lives Matter 757 and an organizer of last year’s protests.

“It’s very significant, but there is still a whole lot more work to be done,” said Jones.

Police brutality and wrongful arrests remain a threat to Black Virginians, he said. And although the Virginia legislature advanced several criminal justice reforms after the protests, it voted down bills to limit qualified immunity. Qualified immunity protects public officials from lawsuits unless the victim can show that they violated a right that had been “clearly established” by previous court decisions. Progressive and conservative critics of the doctrine say it has allowed officers to escape accountability for even the most egregious abuses.

Because of the protests, criminal justice reform became the “preeminent political issue in Virginia and in many other states,” said Michael Stone, executive director of Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. “The police murder of George Floyd changed everything.”

Since the reinstatement of capital punishment, more than 45 percent of those executed in Virginia have been Black, according to DPIC. The two remaining people on the commonwealth’s death row are Black.

“It’s just heartening to see that hearts and minds are being changed,” said state Senator Jennifer Boysko, a longtime death penalty opponent. “When George Floyd died last year a lot of people took a lot of hard looks at their own biases, at their own beliefs, and they educated themselves.”

Prior to the Civil War, Virginia law delinated capital punishment by race: White people could only be executed for first-degree murder, but enslaved Black people could be executed for non-homicide offenses, according to DPIC. This segregated system continued into the 20th century. Between 1900 and 1969, more than 70 Black men were executed for rape, attempted rape, or robbery in Virginia; no white men were executed for these crimes during this time, according to DPIC. During the same time period, 185 Black and 46 white people were executed for murder.

In 1908, Virginia replaced execution by public hanging with the electric chair, but extrajudicial lynchings of Black residents continued. Between 1877 and 1950, there were 84 documented lynchings of Black people in Virginia, according to the Equal Justice Initiative.

Activists with the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy held anti-death penalty prayer vigils in January at locations where lynchings had occurred.

“Virginia’s death penalty is rooted in racial oppression,” LaKeisha Cook, an organizer with the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy, told The Appeal: Political Report. “We stopped lynching Black people and instead started executing them so we just traded in the noose for the electric chair.”

The death penalty still remains on the books in a majority of states, including three states that have gubernatorial moratoriums: Pennsylvania, Oregon, and California. These moratoriums cease executions for the duration of a governor’s term, but the people on death row remain at risk of execution under future governors.

At the federal level, a de facto moratorium existed for 17 years, until last July. In the last seven months of Donald Trump’s presidency, his administration executed 13 people. Two days after President Biden’s inauguration, 37 members of Congress sent him a letter urging him to commute the sentences of all federal death row prisoners. Biden opposes the death penalty.

“Moratoriums are welcome, but they are insufficient,” said Stubbs. “That is absolutely why governors and executives like Biden absolutely should use their powers to grant clemency to ensure we don’t see the kinds of things that we saw under President Trump.”

This legislative session, bills to abolish the death penalty have been introduced in the federal government, in Nevada, in Ohio, and in former Confederate states South Carolina, Texas, and Florida, according to DPIC.

“When Virginia abolishes the death penalty we’ll be the first state in the South to do so,” said Cook, who talked to the Political Report before the governor signed the law. “We can provide the example for other Southern states to follow behind us.”

The story has been updated with news that the governor signed the legislation into law.