Supreme Court Signals It May Empower Legislatures to Subvert Elections

Republicans are pushing the independent state legislature doctrine, which would bolster unfettered gerrymandering and Trump’s efforts to undercut democracy.

Cristian Farias | March 9, 2022

Update: On June 30, 2022, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Moore v. Harper, a case that will test the independent state legislature theory

The U.S. Supreme Court signaled on Monday that at least four justices are ready and willing to bless a legal theory that was never really taken seriously until the 2020 elections. The so-called independent state legislature doctrine, if adopted, would provide new legal cover for Republicans to use their vast powers in states to subvert elections, shield aggressive gerrymanders, and restrict access to the vote in Democratic strongholds at the local level.

Their feverish idea is that state legislatures should have complete and unfettered control over how federal elections are run and regulated, shielded even from the oversight of state courts. Against the backdrop of efforts by President Donald Trump’s supporters to reverse the last presidential election and prepare for the next one, the doctrine would give carte blanche to Republican-run legislatures in swing states like Georgia and Wisconsin, which the GOP has gerrymandered, to ensure it never loses.

In 2020, Texas and other Republican-led states implored the Supreme Court to block certification of the presidential election results in key states like Pennsylvania that Joe Biden won. They claimed that those states had flouted the Constitution and past legal precedents purportedly making it clear that “a single branch of State government”—that is, the state legislature—has the authority to set the rules governing the appointment of presidential electors. Because “executive and judicial officials made significant changes to the legislatively defined election laws in the Defendant States,” Texas insisted, these states had violated the Constitution’s Electors Clause and Elections Clause.

As Texas and its allied states see things, these clauses teach that only a state’s legislature may establish or modify the rules governing who elects the president and other federal offices. All other state “non-legislative actors,” like courts or election administrators, must abide by those rules.

The Supreme Court rejected their plea at the time without opining on the merits. Weeks later, the Jan. 6 insurrection on the Capitol attempted by brute force what the justices wouldn’t do through the force of law.

But Republicans did not move on. Quite the opposite: The independent state legislature doctrine has continued to metastasize and grow legs and gain traction in GOP politics. Last month, Kansas Attorney General Derek Schmidt cited it to try to quash a lawsuit challenging a partisan gerrymander that threatens the congressional district of Democratic Rep. Sharice Davids. “The Elections Clause commits the redistricting power to state legislatures, and no Kansas law—either statutory or constitutional—gives the state courts any role in evaluating the validity of duly enacted redistricting plans,” his office wrote.

Also in February, angered by a North Carolina Supreme Court ruling that struck down their aggressive gerrymander, and by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s work in drawing a new map for its state, Republicans appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court and invoked the independent state legislature doctrine. These courts should not have the authority to intervene in how the GOP-run legislature wants to draw maps and set timetables for the elections, they said.

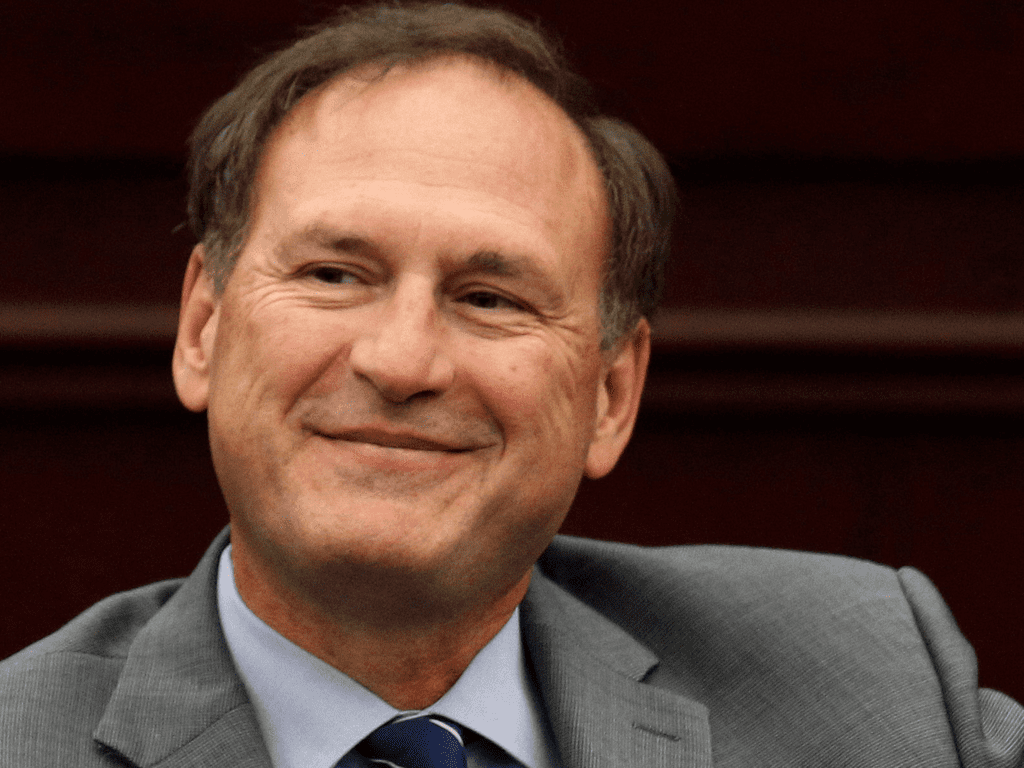

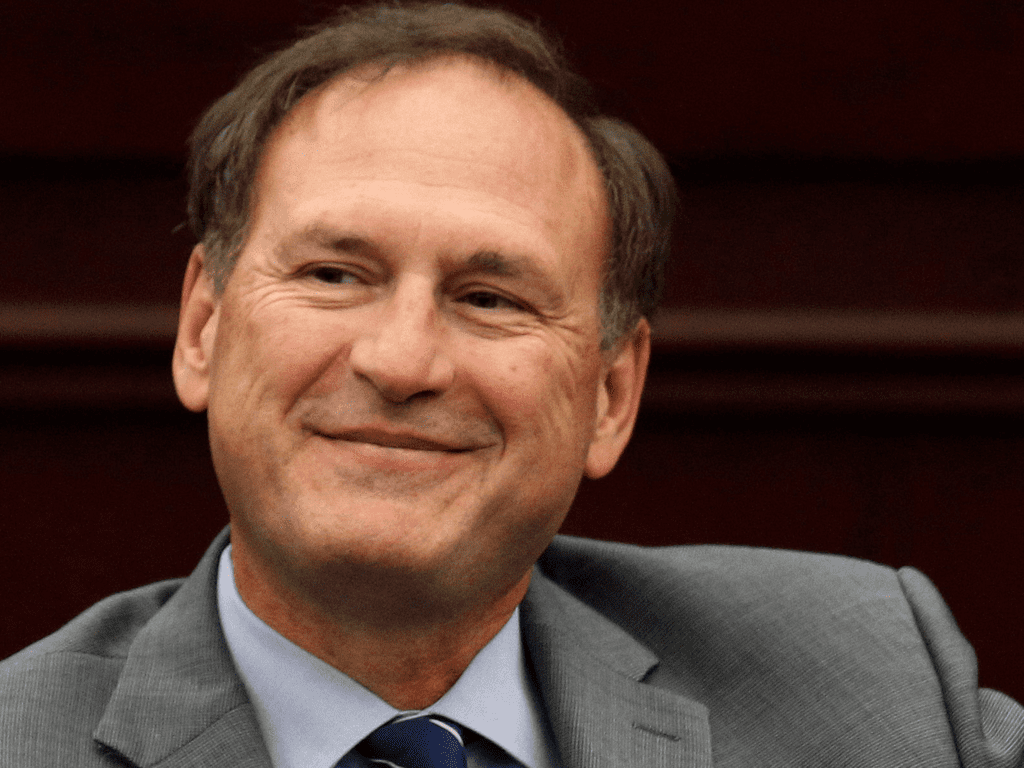

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene on Monday. But its more conservative members, led by Justice Samuel Alito, signaled loud and clear in the North Carolina case that they are open to affirming the supremacy of state legislatures in election administration.

“This case presents an exceptionally important and recurring question of constitutional law, namely, the extent of a state court’s authority to reject rules adopted by a state legislature for use in conducting federal elections,” Alito wrote in a dissenting opinion joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch. “There can be no doubt that this question is of great national importance.”

Alito took issue with the North Carolina Supreme Court for approving a map that the state’s General Assembly opposed. “And if the language of the Elections Clause is taken seriously, there must be some limit on the authority of state courts to countermand actions taken by state legislatures when they are prescribing rules for the conduct of federal elections,” he wrote.

In a separate opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh agreed that the U.S. Supreme Court needed to settle the matter once and for all. “The issue is almost certain to keep arising until the Court definitively resolves it,” he wrote. In predicting that such a dispute would be on the court’s docket sooner rather than later, he effectively invited lawmakers in other cases to continue invoking the doctrine

Amy Coney Barrett didn’t add her name to anything. She is the only conservative justice who hasn’t yet telegraphed her position on theory, giving her the keys to the future of U.S. elections.

And just like that, what once seemed like an esoteric doctrine, now fueled by Trump’s plans for a coup, has gained steam and legitimacy, despite a long line of prior Supreme Court cases rejecting it and Founding-era evidence that the theory is bunk.

As voting rights advocates put it in their brief defending the new North Carolina plan, the doctrine “flouts a century’s worth of this Court’s precedents,” some of them only a few years old. One such case, Rucho v. Common Cause, decided in 2019, was otherwise dispiriting to voting rights advocates because it rejected the view that federal courts have authority to adjudicate partisan gerrymandering claims. But that same conservative majority, which included Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, also assured voting rights advocates that they could at least turn to state courts. “Provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply,” the court said. In other words, the conservative justices made it clear at the time, perhaps to make the bitter pill of their broader ruling easier to swallow, that legislatures don’t have free reign to do as they please. They are dependent on their own state constitutions, which may require free and fair elections, give the governor a say, guarantee equal protection of the laws, and are subject to judicial checks.

In a forthcoming paper that examines how the framers of the Constitution understood the role of state legislatures, law professors and brothers Akhil and Vikram Amar are also adamant that the independent state legislature doctrine has no basis in originalism. “Indeed, at the Founding, the ‘legislatures’ of each state to which Articles I and II refer were, as a general matter far from free agents,” they write. Their work only adds to a growing body of scholarship discrediting the doctrine.

None of this may matter for the U.S. Supreme Court in the end if Amy Coney Barrett sides with her conservative colleagues in a future case. The court didn’t note the grounds for turning away the redistricting case on Monday, but it’s plausible that it did so because we are now too far along in the electoral calendar to alter the rules of the midterm elections in that state. And it left the door open to consider and potentially affirm the doctrine in future cases.

As it stands, Republican officials, including those who supported Supreme Court intervention in the outcome of the 2020 election, are undeterred in invoking it throughout the country.

If they succeed, it could shut down a path that civil rights groups have increasingly turned to as the federal judiciary has veered sharply to the right. State constitutions provide protections that state supreme courts like North Carolina’s and Pennsylvania’s have flexed. In both states, Democrats won key judicial elections to secure majorities willing to do so.

But a suddenly operative independent state legislature doctrine would throw that paradigm out the window. It would weaken state supreme courts’ ability to intervene in election cases. It could be invoked to strike down independent redistricting commissions. And Republican lawmakers could wield it to restrict voting measures in Democratic-led cities and localities wishing to make it easier for their residents to vote.

All told, legitimizing the doctrine strengthens Trump’s hand in the run-up to 2024, undermining many of the remaining checks against his efforts to undercut democracy. Alito and the other justices are granting a veneer of legal respectability to the kind of power grab the former president attempted in 2020 and may again in two years.