In Alabama, an “Out of Control Board” Cuts Chances for Parole

After pressure from the governor and attorney general, denials from Alabama’s parole board have skyrocketed, blocking a key mechanism for release from the state’s overcrowded prisons.

Lauren Gill | November 28, 2023

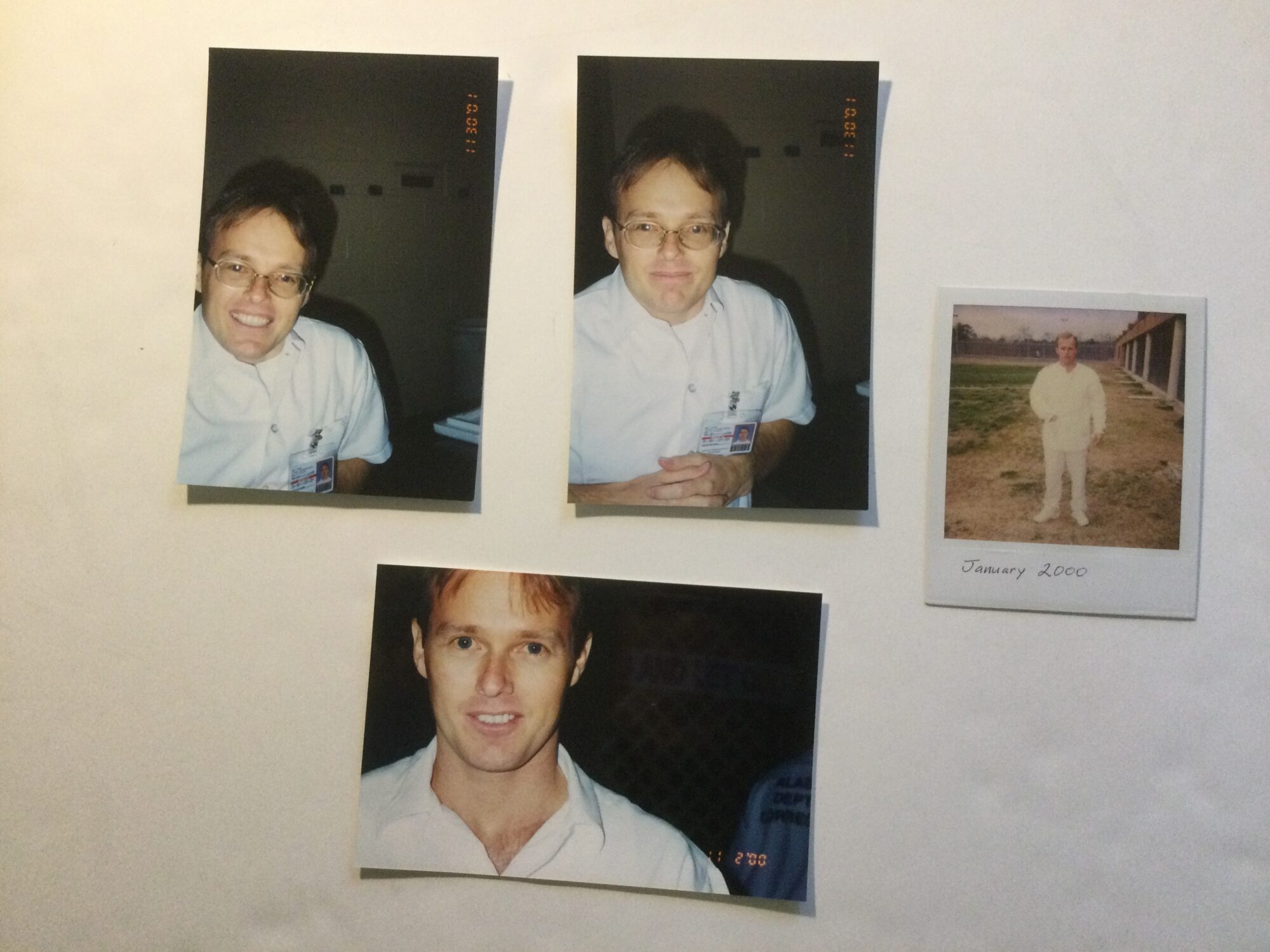

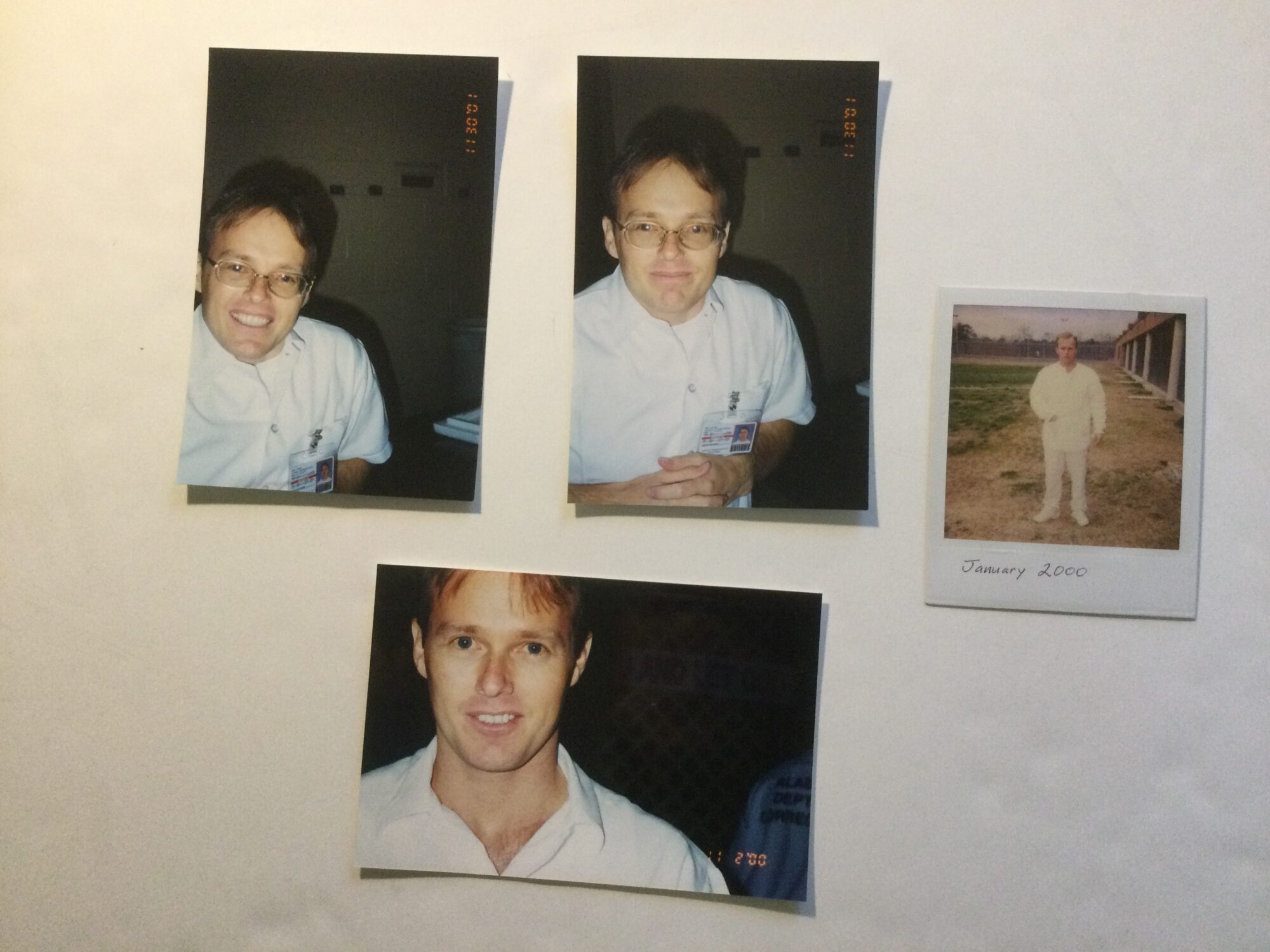

In late July, Treina Kinder traveled about 200 miles from her home in Huntsville, Alabama, to Montgomery to ask the state’s parole board to release her husband, Richard Kinder. He was 17 when he was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to spend his life in prison for his role in the killing of Birmingham teenager Kathy Bedsole. By the time of his parole hearing this summer, Richard had been incarcerated for nearly 40 years.

Walking into the hearing in Montgomery, Treina was optimistic. Accompanying Richard’s application was a long list of achievements like college degrees and 40 certificates, including for the completion of drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs. He’d lived in a faith based honors dorm since 2005 and had only one minor disciplinary infraction during his incarceration at St. Clair Correctional Facility, which has at times been the most violent prison in Alabama, a state that in recent years has had one of the country’s highest prison homicide rates. Richard’s furniture and refinishing instructor at the prison supported his release, writing in an affidavit, “I am 1000% convinced that if Richard Kinder were released, he will not violate the law and will become a productive member of our society.”

Importantly, Richard’s application also included a letter from the former lawyer for his co-defendant, David Duren, who said Duren had admitted the plan to kill Bedsole was his alone and that Richard had no idea he was going to shoot her (Duren received the death penalty and was executed in 2000).

Richard was initially sentenced to life without the possibility of parole, but in 2017, after a pair of U.S. Supreme Court decisions ruled that imposing mandatory sentences of life without parole on minors was unconstitutional, an Alabama judge reduced Richard’s sentence to life with the possibility of parole. The judge wrote there was “uncontradicted evidence” of Richard’s rehabilitation. Even so, the board denied Richard parole in July 2018, his first hearing after he became eligible.

But Treina hoped this summer would be different. “I thought … that we had a really good chance,” Treina told me of the latest hearing. “There’s nothing else he could have done. I mean nothing.”

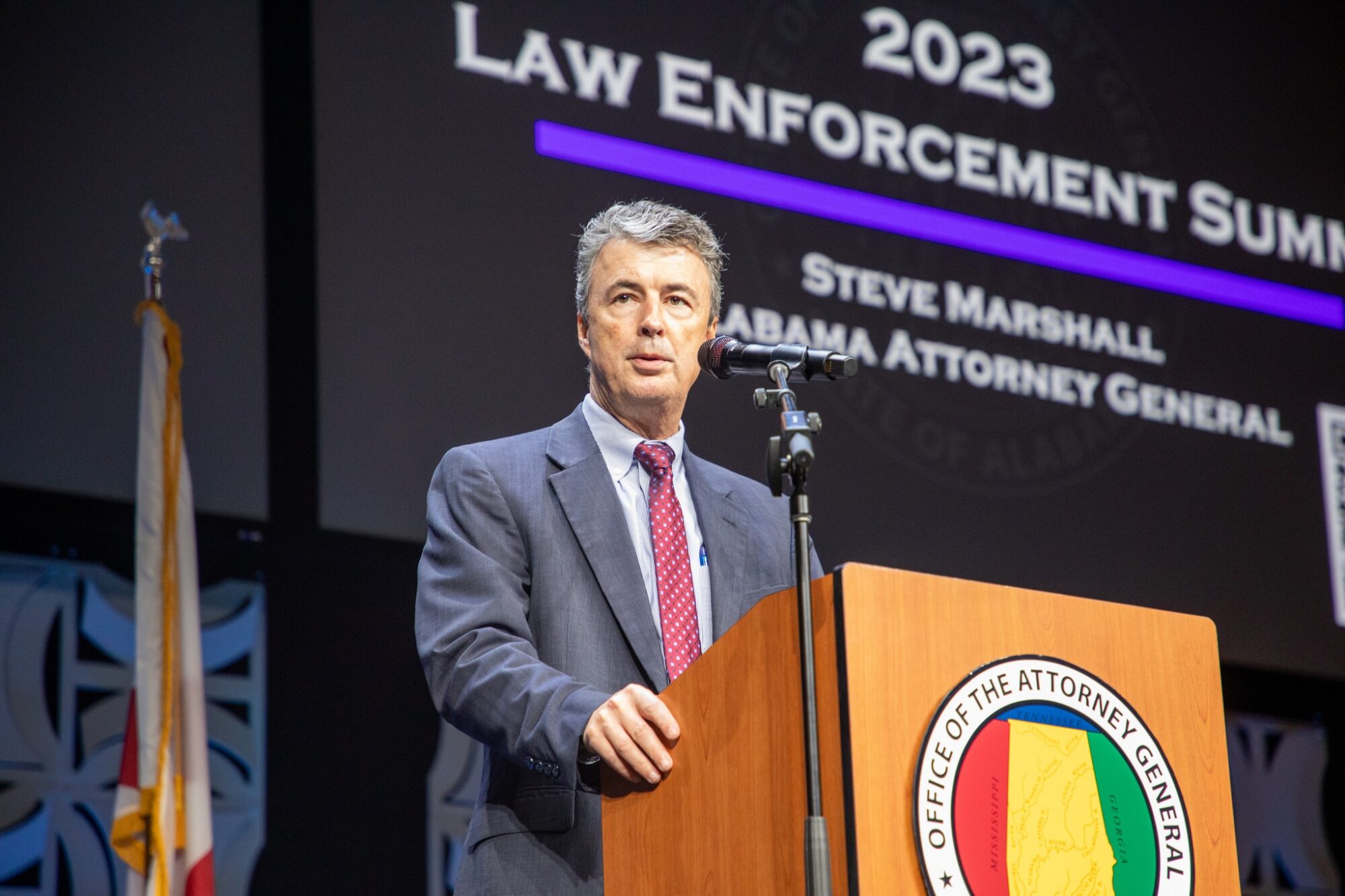

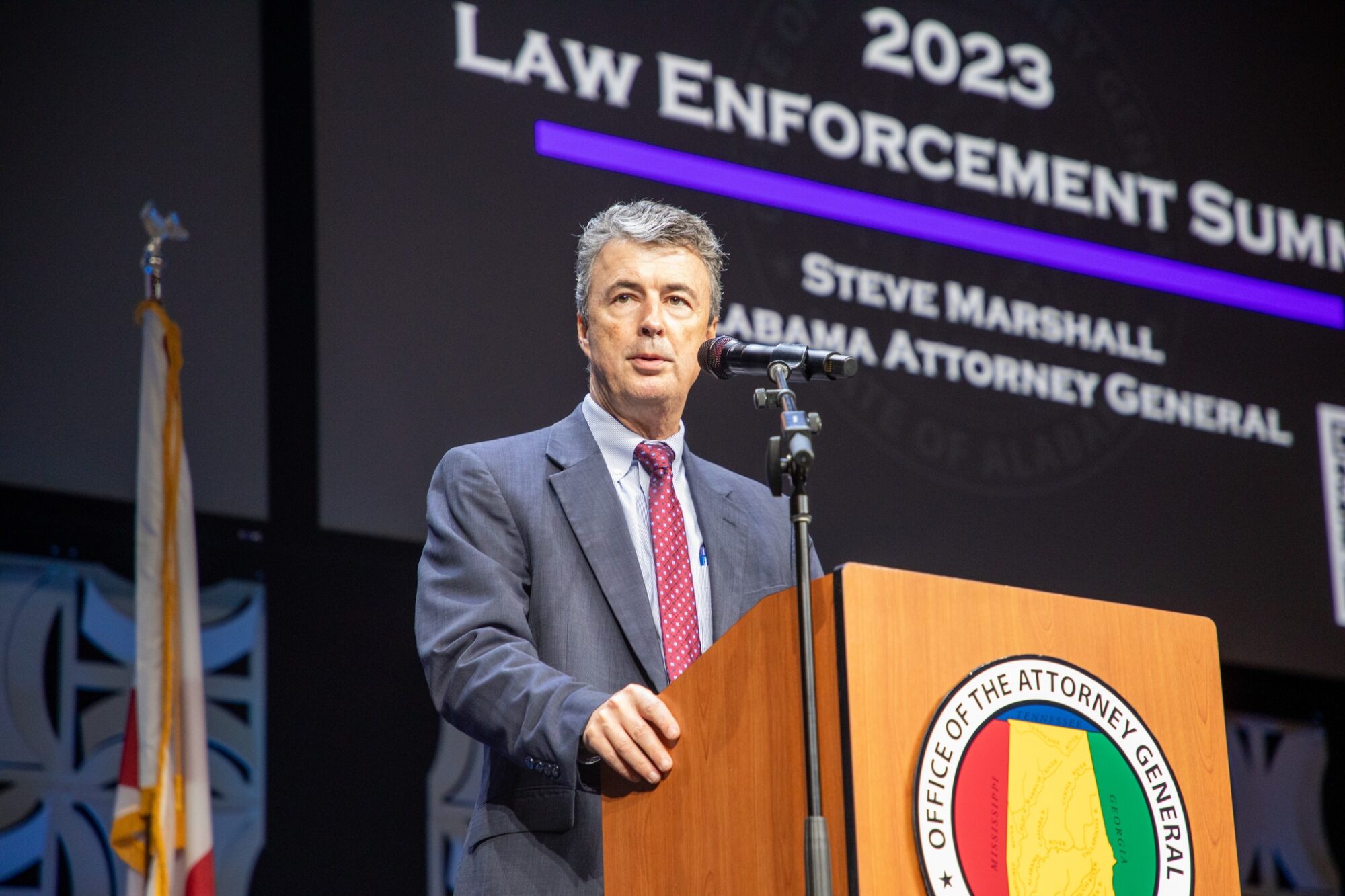

At the hearing, which took place at the parole board’s office, each person was given two minutes to speak in support or opposition of Richard’s release. Treina spoke about Richard’s accomplishments and his plan to live with her and find work in Huntsville. Richard’s brother and one of his lawyers also spoke in favor of his parole application. Bedsole’s sister and father opposed his release, as did a representative from Attorney General Steve Marshall’s office.

Unlike other states, prisoners aren’t allowed to attend their parole hearings, so Richard sent a letter for board members to review ahead of time. “I realize the severity and seriousness of my offenses, and I understand that granting parole to me may be a difficult decision for you,” he wrote. “My hope is that my record will adequately reflect to you the effort I have put into my personal growth and change I have made in my life during the 40 years of my incarceration.”

His lawyer, Richard Jaffe, said the board conferenced for just “a couple minutes” before denying Richard Kinder parole and telling him he’d have to wait five more years to petition them again. A sheet explaining the reasons for denial shows the board decided against his freedom because of the severity of his offense and opposition from Bedsole’s family and the attorney general’s office.

Treina says she broke down crying in the parking lot. “I was devastated,” she said. “I really thought he was going to get out.”

Jaffe said every piece of evidence his team gave the board showed that Richard had been rehabilitated and reformed, and that there was no plausible reason for the denial. “To say it was disheartening would not come close to describing this injustice,” Jaffe wrote in an email.

Since Richard’s first hearing in 2018, it has become even more difficult for people to get out on parole in Alabama, a privilege reserved for prisoners who meet a certain set of guidelines, such as showing they’re unlikely to commit another crime. State parole data shows that people who meet that criteria have been denied release at much higher rates over the past five years, blocking an important mechanism for release from the state’s dangerous and overcrowded prisons. Alabama’s parole board, which years ago released more than half of people who applied, approved just 10 percent of applicants last year. Richard was one of 245 people the parole board denied release from prison in July; the board granted freedom to just 11 people that month, a parole grant rate of four percent.

In many cases, the board points to opposition from the attorney general’s office and a victim’s rights group to support its decision to deny release. Legislative efforts to add oversight and stricter guidelines for the board to follow have failed, even as the board appears to flout constitutional requirements by discriminating against Black applicants.

State Representative Chris England, a Democrat who represents Tuscaloosa and who has introduced bills to reform the board in the past two legislative sessions, told me the board is not following its own guidelines. “What you see, in my opinion, is an out-of-control board,” England said.

Right around the time Richard Kinder first became eligible for release, politics and policies around Alabama’s parole board started to change.

Four days before Richard’s first parole hearing in 2018, a man on parole killed three people. As criticism grew over the board’s decision to grant him parole, Lyn Head, who was chair from 2016 to 2019, says Governor Kay Ivey pressured board members to stop releasing people. Head recounted a meeting in October 2018 led by Ivey and Marshall, who are both Republicans, that set the tone for how the board was expected to vote for people convicted of violent crimes—a category that’s broadly defined in Alabama law to include drug trafficking and third degree burglary and covers approximately 80 percent of people in Alabama prisons.

According to Head, Ivey was puzzled as to why board members would vote to release people who had committed such crimes. “Why would you even consider letting someone convicted of a violent crime go free?” Ivey asked, according to Head.

Head says she explained to the governor that the parole board is required by the legislature to use a risk assessment tool that helps predict whether someone is likely to reoffend, and that people convicted of violent crimes were often considered low risk based on that available data. According to Head, Ivey “banged her hand on the table and said, ‘But don’t you think these people need to pay a price?’”

Head says she started changing the way she voted on cases because of pressure from Ivey and Marshall. “There were cases where I did not vote to parole even though I knew I needed to because I was afraid of losing my job,” she told me, explaining that she had two children in school at the time.

A spokesperson for the governor’s office did not return requests for comment on Head’s account. Amanda Priest, a spokesperson for Marshall, declined to comment.

The legislature passed a bill the next year that gave Ivey even more control over the board. Previously, the governor selected board members from a list provided by a five-person nominating commission that was chaired by the chief justice of the state supreme court; the commission also included the presiding judge of the court of criminal appeals, the house speaker, senate president and lieutenant governor. The 2019 law eliminated the judges from that commission and narrowed it to just the three other leaders of the state legislature. It also gave Ivey power to directly appoint the parole board’s director and added the requirement that at least one member have at least 10 years of experience in law enforcement and “the investigation of violent crimes or the apprehension, arrest, or supervision of the perpetrators thereof.”

Head resigned in the fall of 2019 and Ivey replaced her with Leigh Gwathney, who was a senior prosecutor in charge of violent crimes and assistant attorney general under Marshall in the AG’s office.

After Gwathney’s appointment, parole releases began to plummet, from a grant rate of 53 percent in 2018 to 20 percent in 2020. Last year, the grant rate was 10 percent.

Head attributes the low grant rate partly to Gwathney’s unwillingness to seek training on a risk assessment tool. Under the board’s rules, members are supposed to consider information from a risk assessment as well as an evaluation from a parole officer who looks into people with upcoming hearings. In August, the most recent month with data available, the system found that roughly 80 percent of people met the parole requirements, yet the board granted parole to just five percent of applicants that month.

The board declined to comment on a list of questions about the low grant rates.

Kim Davidson, who served on the board from March to June, told me in a text message that those guidelines “have no teeth” because the board doesn’t have to follow them. She recommended that officials make the guidelines for release presumptive rather than advisory, and introduce an appeals process. Davidson, a lawyer, was appointed to fill in for board member Dwayne Spurlock, who retired before the end of his term. During her short tenure, she voted in favor of parole more often than her fellow board members.

Ivey did not appoint Davidson to another term, however, a snub Davidson blames on Marshall, who she says did not want people to be released on parole. “I could have played the long game and voted more in line with denials and odd set dates,” wrote Davidson. “But, that just isn’t me.” Davidson claimed the attorney general’s influence looms large over the board because of Gwathney, whom she found to mistakenly apply the law at times. “The only thing he needs to do is keep Leigh on the Board,” Davidson said.

Head says the board’s refusal to release people who have worked to change themselves does not improve public safety. She’d like to see more focus on re-entry programs that support people leaving prison and have been proven to reduce recidivism rates. “They want to show or demonstrate to the public that we’re keeping you safe because we’re keeping these people locked up better than anybody has before us,” she told me. “But the problem is, they’re lying to the public. Because if they would explain to the public, this is how you reduce recidivism.”

After I interviewed Head, she reviewed an article I wrote in The Appeal in 2019 chronicling Richard’s case after his first parole hearing. She said she did not remember his case and was puzzled as to why she voted against his parole. “Don’t understand and surprised,” she wrote in a text message. Asked whether she regretted voting that way, she replied that she couldn’t say without looking at his file. “But if there is nothing in the file that indicates his record is other than all that you found, yes,” she said.

When researchers from the ACLU of Alabama observed around 260 parole hearings this summer, they found that Gwathney granted parole less frequently than the other two parole board members. She also maintained an allegiance to her old employer, denying parole in every case that the attorney general’s office opposed, according to their final report.

“I think that any parole hearing that the attorney general’s office opposes, Gwathney should recuse herself. She has a conflict of interest,” said Alison Mollman, senior legal counsel for the ACLU of Alabama. “But that has not been her practice. She continues to sit and vote with her former employer in all these cases.”

The researchers discovered another troubling finding. Since Ivey took over control of the board, Black people were far less likely to be granted parole than white applicants. In 2019, Black and white prisoners were granted parole at similar rates, with 34 percent of Black people granted parole compared to 36 percent of white applicants. But that disparity grew by 2020, with 16 percent of Black applicants receiving parole compared to 29 percent of white people, according to their report.

In the hearings observed by the ACLU of Alabama this summer, white people were granted parole 11.8 percent of the time. Black people had a grant rate of 4.7 percent despite being similarly situated.

Black people incarcerated in Alabama’s prisons also receive sentences that are on average nine years longer than for white people, and spend significantly longer behind bars before receiving parole. A recent analysis of state court data by AL.com found that nearly half of Black men granted parole over a two month period this year had already served at least 75 percent of their court-ordered sentence. White people granted parole during that same period had served, on average, less than a quarter of their sentence.

Shrinking parole has also become a barrier to alleviating overcrowding inside a prison system so dangerous that the U.S. Department of Justice has sued the state and the Alabama Department of Corrections after an investigation showed excessive force by correctional officers and “serious risk of death, physical violence, and sexual abuse at the hands of other prisoners.” There were roughly 19,800 people in the state’s men’s prisons at the end of September yet the facilities are designed to hold just around 11,700.

“I think that when we see how violence has just skyrocketed in Alabama’s prisons, it’s directly related to the lack of hope that people have,” Mollman told me.

Despite these problems, there’s been little movement from the legislature and Ivey’s office to make it easier for people to get out on parole. For the past two years, England, the Tuscaloosa lawmaker, has introduced legislation that would create a panel to oversee the board and create guidelines for members to follow. It would also require the board to issue a written decision when deviating from those guidelines and create an appeals process for prisoners. “They don’t have to follow guidelines and it’s completely discretionary,” England said. “So when you don’t have any oversight, you get systems that are clearly abusing the discretion that they have.”

England’s bill failed to gain traction among other legislators, some of whom deny there are any problems with the parole board. “I’ve spent 25 years with Pardons and Paroles and I just want to say that it’s a hoax that the parole board is not releasing folks,” Representative Jerry Starnes, a Republican who represents Prattville, said in a House Judiciary Committee hearing on the bill earlier this year, according to the Alabama Political Reporter.

As chances for parole shrink in Alabama, people inside its prisons are confused about what they can do to earn their freedom.

In a telephone call from St. Clair Correctional Facility, where Richard is incarcerated, he talked about the board’s focus on the crime he was a part of 40 years ago. “Look at the reasons why they turned me down for parole and they’re reasons that I can do nothing about. Capital murder is always going to be a severe offense, I can’t change that,” he said.

He’d followed the parole board since his last hearing and knew it had become much harder to get out, he said. Going into his hearing this summer, Richard said he was hopeful but not optimistic about the board voting in favor of him. “They would have to be willing to really look at our record, you know, what we’ve done in here, and say, ‘Hey, this warrants a chance.’”

Still, he expressed remorse for his role in Bedsole’s death. “I mean, how much time is enough?” he asked. “I don’t know… When I look at myself, personally, I think about a 16-year-old girl that’s lost her life. I don’t know how long she would have lived. You know, she may have lived way older than me. I don’t know how much time is fair for her life. How much time is fair for me to do regardless of who I am in here and how I changed or anything?”

Stay up-to-date

Now is the best time to support Bolts

NewsMatch is matching all donations (up to $1,000) through the end of the year. Support our nonprofit newsroom today.