Kansas Voters Reject Constitutional Amendment to Erode Abortion Rights

The first referendum on abortion since the fall of Roe underscores how state constitutions have become new battlegrounds for reproductive rights.

Quinn Yeargain | August 3, 2022

Kansas voters on Tuesday rejected a proposed constitutional amendment barring any recognition of abortion rights under the state’s constitution, marking the first state referendum on reproductive rights since the U.S. Supreme Court struck down federal protections for abortion access five weeks ago.

The victory for abortion rights advocates was decisive, with 61 percent voting to reject the amendment as of publication. It is the first major win for abortion rights advocates following the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling on June 24 overturning Roe v. Wade. The vote also keeps in place a Kansas Supreme Court ruling three years ago that held abortion rights were protected under the state’s constitution.

“I think this was a passionate issue for folks, it goes beyond party lines, it’s about health care,” said Christina Haswood, a Democratic member of the Kansas House of Representatives from a district around Lawrence. Haswood, who is Navajo and the youngest member of the legislature, pointed to high mortality rates for Native people who are pregnant. “As a young Indigenous woman, at the end of the day this boiled down to life or death.”

The state’s urban and suburban areas rejected the measure by huge margins, up to 85 percent to 15 percent in Douglas County, which contains Lawrence. And while the amendment largely carried the state’s rural counties that vote massively Republican, the margins were considerably tighter than these areas’ usual red hue.

Tuesday’s vote highlights the critical role that state constitutions are playing in setting the landscape for abortion access and criminalization after Roe. The federal Constitution sets a floor for what’s considered a protected right, but states are free to set higher standards, and judges often interpret state constitutions and bills of rights more expansively. Two doctors sued to challenge Kansas’s 2015 law banning dilation and evacuation abortions (the most common procedure for second-trimester abortions), arguing that Section 1 of the Kansas Bill of Rights—which protects “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” language borrowed from the Declaration of Independence—sets such a higher standard for abortion rights.

In 2019, most of the Kansas Supreme Court agreed. The court ruled 6–1 that the state constitution “acknowledges rights that are distinct from and broader than the United States Constitution,” including the right to “personal autonomy,” which the judges wrote “allows a woman to make her own decisions regarding her body, health, family formation, and family life—decisions that can include whether to continue a pregnancy.”

The Kansas legislature responded by putting the question directly to voters, with a constitutional amendment to overturn the state supreme court’s ruling on the ballot. But rather than risk the issue being decided in the higher-turnout general election, lawmakers called a “special election” that coincided with the primaries, which historically see lower turnout from Democratic and moderate voters in the state. Election-denying conservatives around Wichita who supported the amendment also spread lies about voter fraud to try and pressure local officials to remove ballot drop boxes ahead of the election, according to The Wichita Eagle.

But turnout was considerably higher than in past primary elections, suggesting that the debate on abortion had a mobilizing effect on the electorate. In Wyandotte County (Kansas City), the turnout rate on Tuesday was 35 percent, compared to 25 percent in the last midterm primaries.

The amendment’s defeat on Tuesday means that the Kansas Supreme Court’s ruling affirming the right to an abortion remains the law in the state.

But uncertainties remain regarding the long-term viability of the current constitutional protections. Two new justices have been appointed to the court since its 2019 decision, and though they were both appointed by the Democratic governor, the state’s nonpartisan judicial nominating process means that the ideological leanings of appointees aren’t always clear. With a Democrat currently in the governor’s mansion, wielding veto power, the Kansas legislature has not had the opportunity to outlaw abortion in the aftermath of Roe v. Wade; such a ban could force the state supreme court to weigh in again on the issue in the coming years.

The upcoming November elections will further reshuffle the balance of power over the issue. The state has a fiercely competitive gubernatorial election between Democratic Governor Laura Kelly, who supports abortion rights and opposed the amendment, and Attorney General Derek Schmidt, who clinched the Republican nomination tonight; Schmitt opposes abortion and supported the amendment.

The governor’s race is one of several in the country that will decide if conservatives are able to push through new restrictions next year “I just hope that I’m here to modify whatever comes forward” in the next legislative session, Kelly said before the election. Even if Kelly were to win re-election, conservatives hope to gain ground in the legislature to secure a veto-proof majority against abortion.

Additionally, six of the seven justices on the Kansas Supreme Court face retention elections this year, which means voters will choose “yes” or “no” on whether each justice should serve another six-year term; several were on the court in 2019 and ruled in favor of abortion protections. The seventh justice, Eric Rosen, hits the mandatory retirement age of 75 in 2028, meaning that the next governor will pick his replacement. Though no supreme court or appellate judge has ever lost a retention election in Kansas, there have been several close calls recently. And since abortion protections in the state rest on a decision by the court, anti-abortion advocates already have plans to unseat the more liberal justices on the court this year.

The saga in Kansas also underscores how state constitutions have become new battlegrounds for abortion rights. In states with “trigger” laws that automatically banned abortion following the U.S. Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe, litigation began almost immediately attempting to block the anti-abotion laws under state constitutions—despite early successes, it’s unclear how that strategy will play out in states with conservative judiciaries.

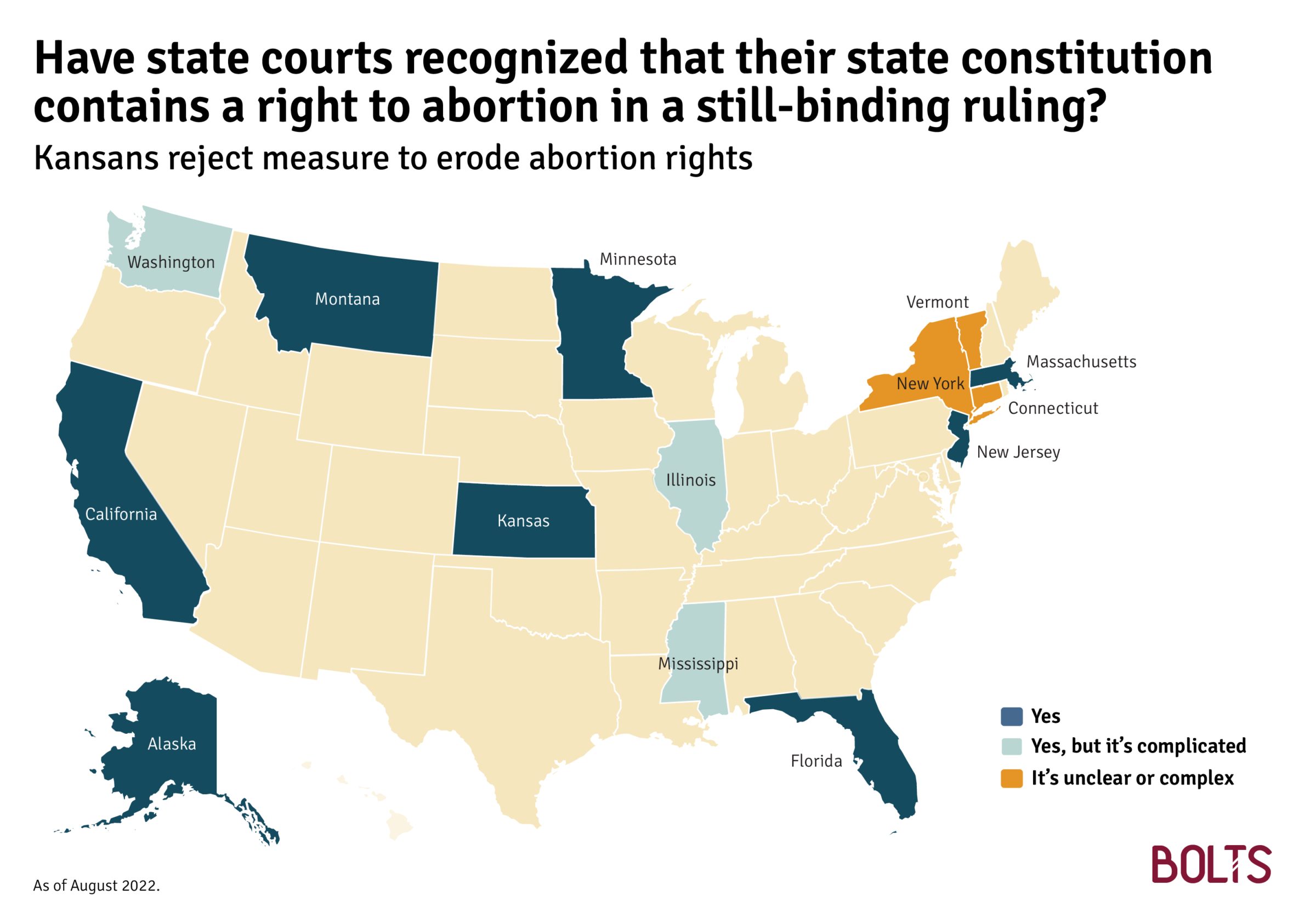

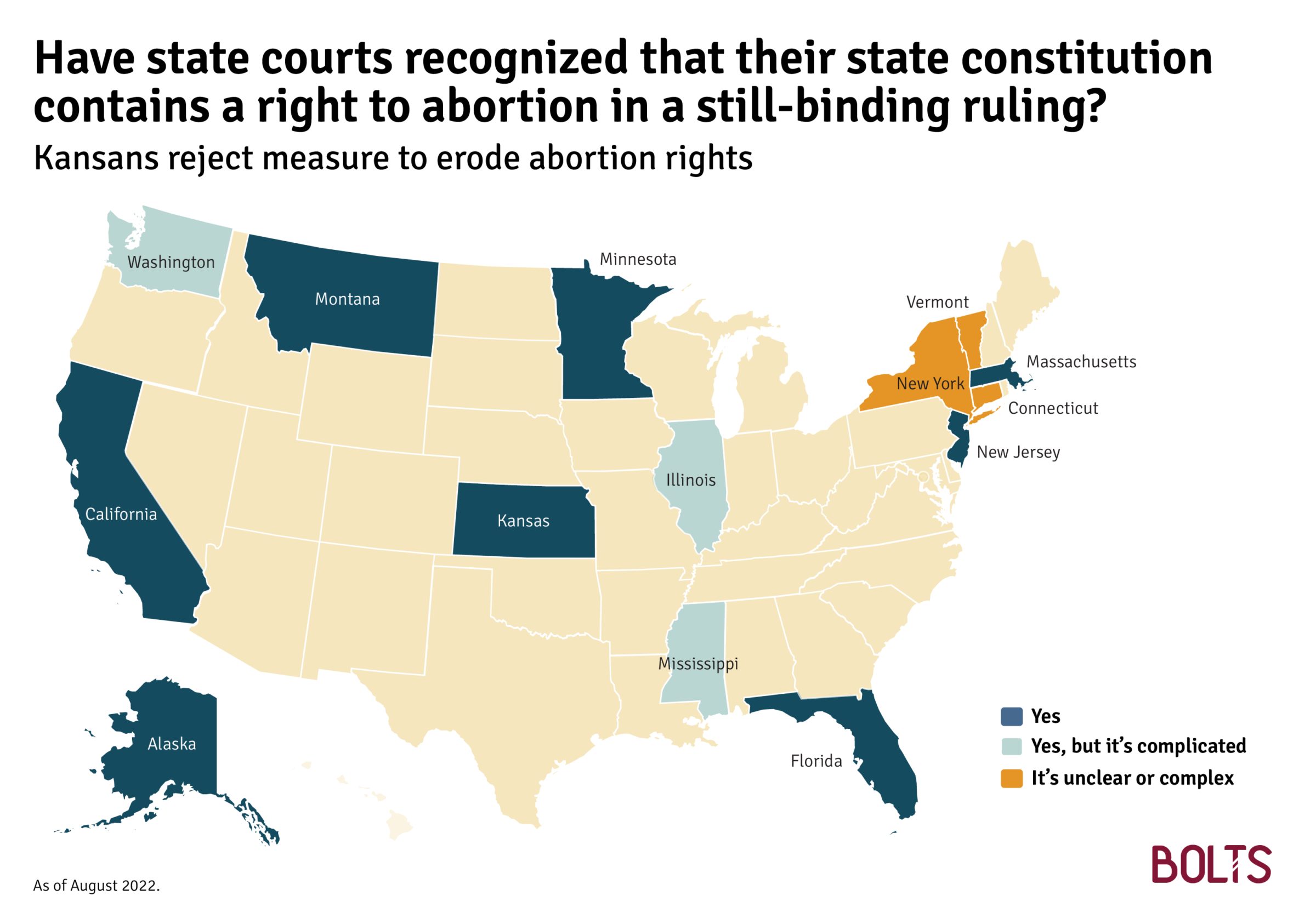

After the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs, Bolts published a nationwide survey of the status of abortion rights under state (and territorial) constitutions. With today’s results in Kansas, there remain eight states where a still-binding ruling by state courts unambiguously affirms a right to abortion, with some confusion over the situation in a half-a-dozen additional states.

The landscape is likely to continue changing. Supreme court elections are on the ballot this year in many states, which could affect the status of abortion rights in a number of swing states such as Michigan and North Carolina in coming years.

And voters will pass judgment on similar amendments. Later this year, voters in Kentucky will approve or reject a nearly identical amendment, and voters in California and Vermont will vote on adding explicit protections for abortion rights in their state constitutions. Voters in Michigan may vote on a similar measure, as abortion rights advocates recently submitted more than 700,000 signatures for an initiated constitutional amendment that would protect abortion rights. With Democratic governors calling for constitutional amendments to safeguard abortion rights in their states, other amendments could be on the ballot this year—or in the coming years

“[T]he story is much bigger because it reveals that abortion rights are supported even in the reddest states and that Republican legislatures are legislating in a way that is out of step with their constituents,” said Greer Donley, an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law who has written extensively on abortion rights.

“It also creates a playbook for restoring abortion rights on a state-by-state basis, even in red states,” she added. ““The important thing about these amendment votes is that they detach party identity from abortion politics and allow voters to vote on the issue without having to abandon their party. They could be the way forward.”