New Washington D.C. Bill Would End Voter Registration As You Know It

The D.C. council will consider setting up a database of residents the city has verified as eligible to vote, expanding on its current automatic voter registration system.

Alex Burness | September 12, 2022

Editor’s note: This legislation became law in March 2023.

Washington, D.C., may soon do away with voter registration as most Americans know it. Under a new bill, set to have its first council hearing on Friday, D.C. would mail ballots to people it knows are eligible, even if they are not registered.

Drawing inspiration from Colorado, which many voting-rights experts characterize as the national standard for accessibility, the city would take information it collects when residents interact with the Department of Motor Vehicles and other agencies to maintain a constantly-updating list of people who are “preapproved” to vote. For people on that list, all there would be left to do is to vote come election time.

“Traditionally, registration has been used as a way to keep people from voting,” Charles Allen, the D.C. councilmember who is sponsoring the legislation, told Bolts. “It’s a way to be a gatekeeper as to who you think should be able to vote.”

Under Allen’s bill, voting itself would be the act of registration—at least for those the city identifies as prequalified. This would “make sure we are really reaching every single person we possibly can to make sure they can participate and have their voice heard,” Allen said.

D.C. already enacts a policy known as automatic voter registration. First adopted in Oregon in 2015, it has since spread to more than twenty states, plus D.C., as a tool to expand voter rolls. (It largely exists in Democratic-run states, with some exceptions.) The idea is that instead of the traditional approach of waiting for people to opt in being registered, agencies like the DMV make it the default to register them to vote and then give them the opportunity to opt out of the rolls. Studies have found that this policy has boosted registration and turnout rates.

But in most places with automatic voter registration, the policy is falling short of its promise. Many people who enter the DMV unregistered are still not registered when they leave. Neal Ubriani, policy and research director at the Institute for Responsive Government, an organization that promotes efficiency in government, and an advisor to Allen on the D.C. bill, says this boils down to how these systems are designed.

When they go to to the DMV to apply for a driver’s license or get an ID card, D.C. residents are currently told that their information will be used to register them to vote, they are shown a list of criteria they must meet, and they are given the option to refuse registration by checking a box: “I decline/opt out. Do not register me to vote or update my voter registration.”

Ubriani said systems like D.C.’s on average have about a 50 percent opt-out rate. Some just want to leave the DMV and think that by opting out they’ll avoid more time and questions; some may not be sure whether they are eligible; others might trust themselves to update their voter registration on their own; or they may believe (falsely, in many cases) that their registration is up-to-date and not tied to a previous address.

D.C.’s design is known as “front-end” since people are asked whether they want to opt-out while still at the DMV. Most states with automatic voter registration do the same.

“I’ve seen states that call themselves AVR systems that have an 80 percent declination rate at the DMV,” Ubriani said.

Allen wants his bill to fix that problem. “We already have a version of automatic voter registration, and this really takes it further,” he told Bolts.

Allen says he looked toward the handful of states like Oregon, Alaska and Colorado that have gone a different route, implementing a design known as “back-end” automatic voter registration. There, people who provide documents that indicate that they are U.S. citizens are automatically registered to vote and they are not asked any further questions while at the public agency; they later receive a mailer at home, and they can return it if they wish to opt-out. If they do nothing at all, they will remain registered to vote.

Colorado switched from a “front-end” system to a “back-end” one in 2019, and a recent study conducted by two political science professors at Stanford University found that the switch successfully activated voters. It drastically cut down the rate of people who opted out: Less than one percent of the people who were sent a mailer returned it indicating they declined registration. This sent registration in Colorado soaring, roughly doubling the registration rate for DMV customers who were previously unregistered. About 250,000 Coloradoans were automatically registered to vote during the first year of implementation, and about half voted.

Amanda Gonzalez was a voting rights advocate as then-executive director of Common Cause Colorado in 2019 when she helped draft and lobby for these changes. “I think the question we probably should be asking ourselves is, what is the system that is going to best facilitate the most participation?” she told Bolts.

Allen has an answer, telling Bolts, “We want to make it as automatic as possible.”

His bill would not exactly move D.C. to a “back-end” system like Colorado’s because it wouldn’t outright register people. But it’s guided by a similar principle that it’s really up to public authorities to review someone’s eligibility based on the information they’ve already shared. Under his proposal, as long as someone has provided certain documents, the city would verify and record them as eligible: This would pre-qualify them as voters, even when they’re not formally on voter rolls.

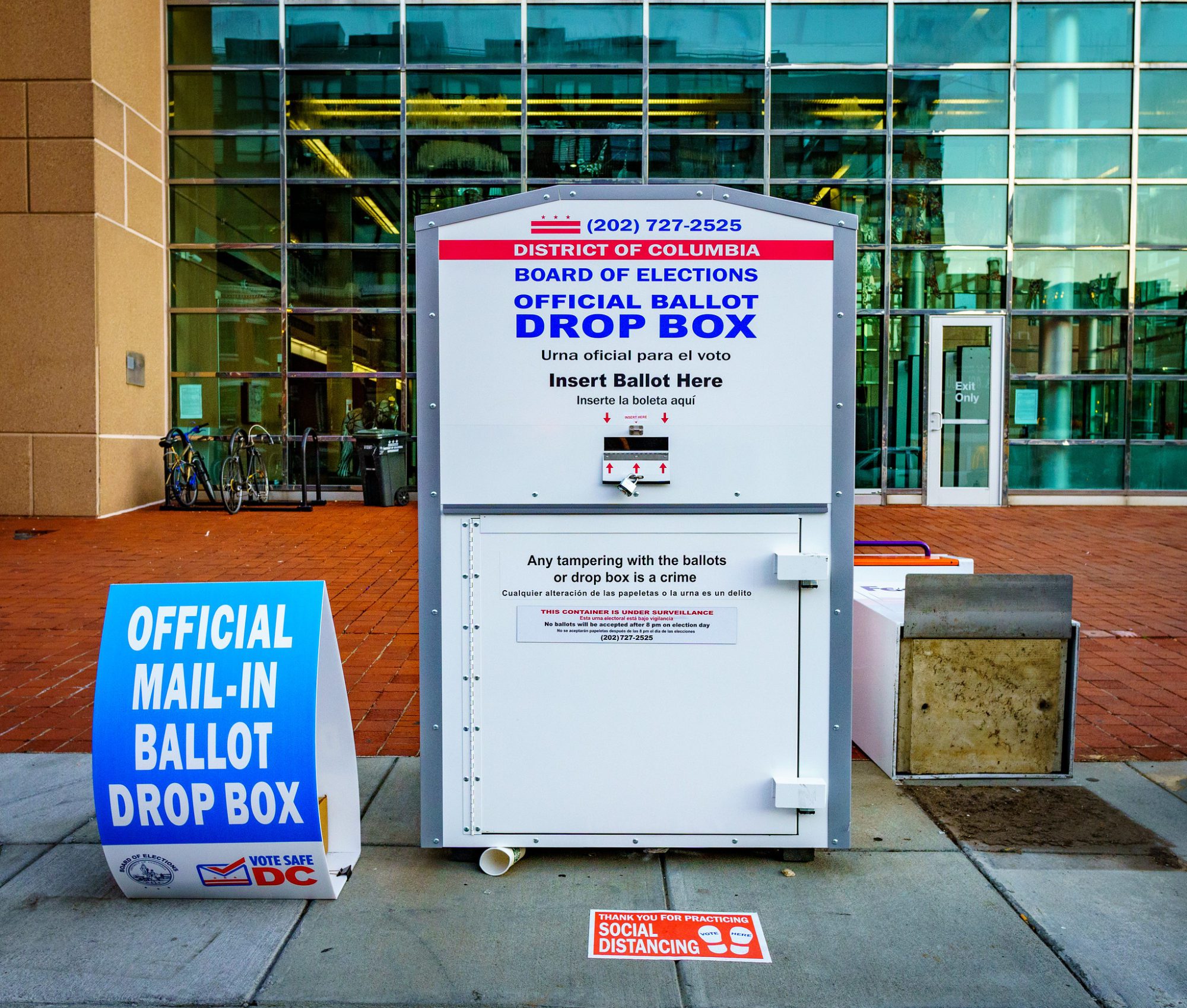

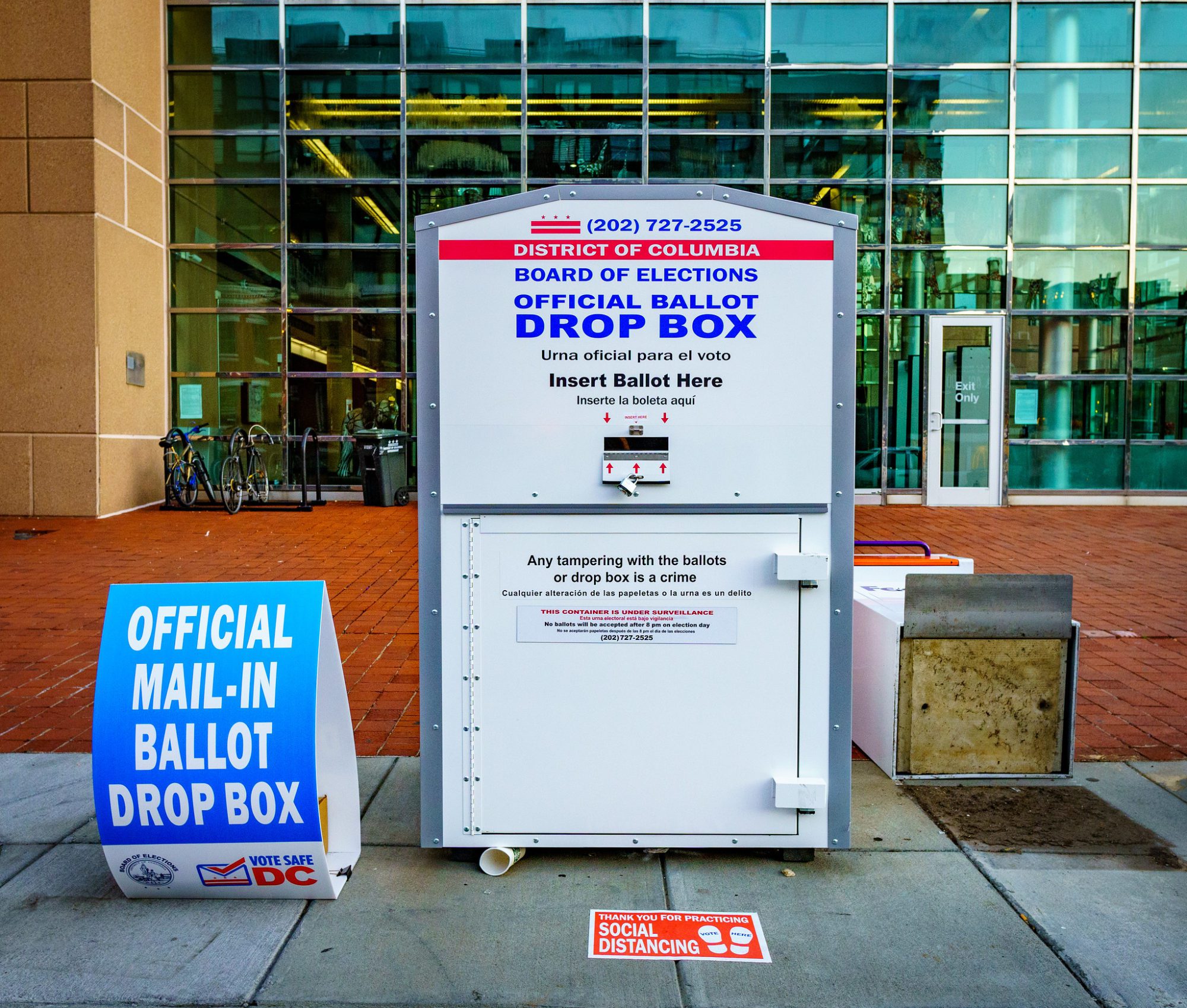

D.C. would then send people on this preapproved list a mail-in ballot for every election during the following two years. They would never need to proactively register, though they would be given an opportunity to remove their name from this list through a mailer. D.C. would also inform them that they can return a ballot or head to the polls to activate their registration. All they would need to do at that point is choose whether or not to vote.

Ubriani thinks that this would break the mold of how we usually approach elections. “It’s not mythologizing this first antecedent step (registering to vote) as some important, necessary civic duty,” he said.

Alex Keysarr, a Harvard historian who studies the development of voting laws in the U.S., has documented that the emergence of registration laws made voting a two-step process that had exclusionary effects.

Voter registration requirements gained widespread popularity in the U.S. starting in the 1870s. The result was to deny some people the ability to vote, or at least to make exercising their right more difficult. “We know historically that those people have tended to be poor people and people of color and immigrants—people who haven’t had the resources,” he told Bolts.

He added, “It creates a barrier between the voter and the act of voting.”

The bill pending in D.C. would chip away at that barrier. Still, the policy would only cover people who interact with select agencies, mainly at the DMV and when filling a Medicaid application. What of people who don’t go to those agencies? There are efforts nationwide to include automatic voter registration with a broad array of public services—–some of which would need approval from the Biden administration—and some want to eliminate voter registration altogether.

Allen says he’s open to expanding his D.C. proposal to use data collected in other settings— perhaps at libraries or public recreation centers—to build a more comprehensive “preapproved” list of voters.

That can get tricky, though. The DMV is an ideal setting not only because it’s a place visited by people of all socioeconomic backgrounds, ages and races. It’s also a place where citizenship questions are already being asked, and all sorts of information relevant to voting, such as age and home address, are already collected. With relatively low effort, a government interested in boosting participation can simply use information the DMV was going to gather anyway.

Expanding this program to, say, libraries or recreation centers would mean asking people about their immigration status in more settings, citizenship being an obvious prerequisite to voting, and that’s a step many balk at.

“I love the idea of libraries, but those aren’t places that currently do citizenship checks, nor should they be,” said Gonzalez, the Colorado advocate who is now the Democratic nominee running for county clerk in Jefferson County, outside of Denver. “We don’t want to create new places where people are being asked to verify their citizenship.”

Some voting right organizations like the Brennan Center worry about these immigration issues even at the DMV, which has led them to criticize “back-end” systems; they say that registering people without asking them immediately if they want to opt out could mistakenly add noncitizens to the polls.

Ubriani says that these risks are already present in D.C.’s current “front-end” system, which is designed to pose registration-related questions to DMV clients even when they are not U.S. citizens. That means people who affirmatively show a document making clear their lack of citizenship still get asked about voter registration. “That’s sort of like a trap for the unwary,” Ubriani said. “If I miss that question, if I’m less English-proficient or confused, even slightly inattentive during the transaction, suddenly I’ve incorrectly indicated citizenship.”

For Ubriani and Allen, this hazard adds to the flaws that they want D.C. to urgently fix.

Allen chairs the committee that his bill will start in, which makes for strong odds that the bill will advance past its first hearing on Friday. The bill would then have to be approved by the full city council and the mayor, and Congress would need to not intervene to repeal it.

The councilmember is simultaneously sponsoring a bill to enact universal mail voting; in 2022, all registered voters in D.C. are already set to receive a mail-in ballot due to pandemic-era rules, but this bill would make that permanent. Allen has also backed other measures to expand participation, including the landmark law that enabled people to vote from prison starting in 2020.

“Unlike other parts of the country where we’re seeing people try to restrict the ability of people to get to the polls and to vote,” Allen said, “in D.C., we want everyone to be able to vote.”

—

Editor’s note: Neal Ubriani was a member of the board of directors of the nonprofit organization that runs Bolts from July 2021 to January 2022.