Campaign Finance Reformers Hope to Convert Their First State to Democracy Vouchers

Bills introduced in New Hampshire and Minnesota would emulate a reform that some West Coast cities have adopted to democratize fundraising.

Spenser Mestel | February 2, 2023

Despite New Hampshire being one of the least populated states in the country, with just 1.4 million people, its elections can be incredibly expensive. In 2020, more than $23 million was spent on the U.S. Senate race, which equates to roughly $30 per vote cast, and the cost of its races for governor and state legislators was another $9.5 million.

That flow of money isn’t transparent, says Olivia Zink, executive director of Open Democracy, a nonpartisan group that advocates for public campaign funding in New Hampshire. “You can drive a Mack Truck through the loopholes in our current campaign finance system,” she says.

Political action committees can make unlimited contributions in the state, an individual can donate up to $15,000 to a candidate in state elections every cycle, and companies can evade contribution limits by funneling the money through different LLCs, she says. Meanwhile, a significant portion of campaign contributions come from outside of New Hampshire, though it’s difficult to know exactly how much because of weak reporting.

With a bill recently introduced in New Hampshire’s House of Representatives, reformers like Zink hope to flip the current system on its head. The bill creates a “voter-owned certificate” program (a system also known as “democracy vouchers”) intended to encourage small donations, disempower wealthy donors, and limit the influence of out-of-state contributors.

The program would mail every eligible voter four $25 vouchers during each two-year election cycle. Recipients could then donate any or all of those vouchers to candidates who have opted into the system and agreed to abide by certain restrictions.

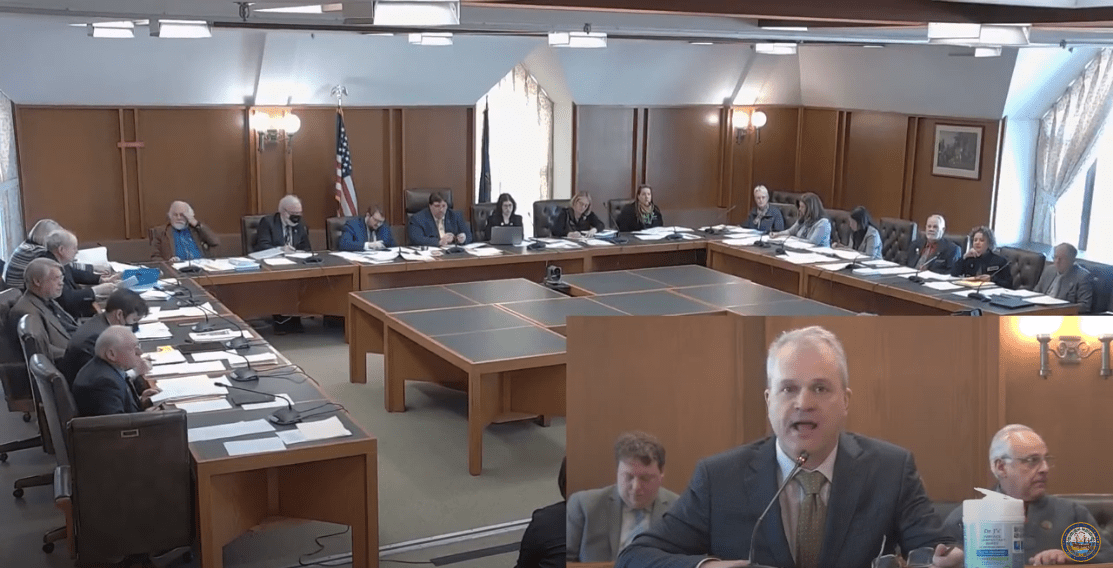

“In every election, there’s a primary before the primary, it’s called the donor primary,” Russell Muirhead, the Democratic lawmaker who introduced House Bill 324, said on Tuesday during a hearing of the state House Election Law Committee. “This bill tries to eradicate that donor primary and give the power back to New Hampshire voters.”

The proposal mirrors a campaign financing system implemented by Seattle in 2017. There, democracy vouchers have diversified and grown the pool of people giving money to political campaigns, and made city races more competitive in the process.

Seattle’s program won its first convert in late 2022, when Oakland voters approved a local ballot measure that will create a “democracy vouchers” program in future city elections.

Now, proponents are dreaming bigger and hope to set up such an initiative at the state level. In addition to New Hampshire, Minnesota Democrats have proposed creating “democracy vouchers” as part of a broad voting rights package they introduced this year, shortly after taking control of the state government.

For a state to adopt this campaign funding model would be a huge boost for the democracy vouchers movement, according to Adam Eichen, executive director of Equal Citizens, a national nonprofit that advocates for election reform.

“The significance of winning the first statewide democracy voucher program cannot be overstated,” he says. “We see again and again that all it takes is one state to be a leader on an empowering, novel democracy policy and the idea will quickly spread across the country.”

HB 324 would bring democracy vouchers to New Hampshire’s highest-profile elections. At least at the beginning, the only eligible races would be for governor and executive council, the five-member body that has veto power over pardons, gubernatorial nominations, and contracts with a value greater than $10,000. Zink says these council races used to be sleepy affairs but have become much more contentious recently, especially after the group voted against multiple rounds of contracts with Planned Parenthood.

Participating in New Hampshire’s program would be voluntary for candidates, and gubernatorial candidates would become eligible only after collecting 2,500 small-dollar donations (500 for executive council candidates). Those who qualified could get up to $420,000 in vouchers for the governor’s race ($84,000 for executive council), and they’d also be eligible for a $1 million grant for a contested general election ($60,000 for executive counselors) in addition to any money raised with voter vouchers.

In exchange, candidates would have to heed certain restrictions, like a cap on personal donations to the campaign, a limit of no more than 10 percent out-of-state contributions, and a ban on soliciting independent expenditures.

In Seattle, where the requirements are similar, the program applies to a wide swath of municipal elections, and has been enormously popular. The current mayor, city attorney, and seven of the nine city councilors used the program in their last election. Meanwhile, the number of donors per race has gone up by 350 percent, and candidates reported hundreds of thousands more in donations of under $200, reducing their reliance on a small batch of wealthy donors, according to a study of Seattle conducted by Alan Griffith, a scholar at the University of Washington.

The same study also found an 86 percent increase in the number of candidates and a large decrease in incumbent electoral success, suggesting that races have become more competitive. Meanwhile, anecdotal evidence suggests that the program is attracting new kinds of candidates as well. Teresa Mosqueda, a labor organizer who launched her 2017 campaign for city council while working full time, renting a one-bedroom apartment, and still paying off student loans, said the program’s existence pushed her to run.

Compared to traditional cash donors of the kind who regularly participate in elections, the voucher users were also more likely to be young and lower-income contributors, according to a 2020 study conducted by researchers at Stony Brook and Georgetown Universities.

Activists in Oakland were eager to realize these outcomes, especially amid a torrent of outside funding in their elections. In 2020, wealthy donors poured more than $1.2 million into pro-charter groups supporting school board candidates, most of whom ended up winning. In fact, between 2014 and 2020, 77 percent of all the city’s contested races were won by the candidate who raised the most money.

After Oakland’s city council agreed to refer the measure to the ballot, voters approved it by a nearly three-to-one margin last November, and the program is scheduled to begin next year.

Muirhead, the lead sponsor for the New Hampshire bill, is excited that a person might feel more invested in the electoral process after they donate to a candidate.

“That ties them to a person, to a campaign, maybe even to a movement or a party, and that’s a really cool thing,” Muirhead told Bolts. Besides sitting in the House, Muirhead is a Dartmouth University professor who researches the theory and practice of democracy; he is teaching a course this year on the phenomenon of “democratic erosion.”

Should his proposal pass and succeed, the commission responsible for its administration could recommend that it be expanded to candidates for the state legislature, and then again those for the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives.

However, the bill is facing a number of obstacles. Its main two sponsors are Democrats, but Republicans control both chambers of the state legislature—even though Democratic candidates made major gains in and nearly tied the state House in November.

On Tuesday, the House Election Law Committee, which is split evenly between Democrats and Republicans, deadlocked 10 to 10 on the legislation. This means that the bill moves to the House floor without a recommendation of the committee.

The vice chair of the committee, Republican Ross Berry, was among those who voted against it.

“I am opposed to these sort of taxpayer funded schemes because they violate the freedom of association and speech by forcing taxpayers to finance political campaigns that they may disagree with,” Berry told Bolts in an email.

Still, Zink believes that the legislation has enough bipartisan support to pass the state House floor but that supporters need to persuade another Republican to lend in the Senate. They must also convince Republican Governor Chris Sununu, who has raised over $2 million from industry groups over the 13 years he’s been in office, especially real estate ($364,000), lawyers and lobbyists ($282,718), and automotive entities ($181,210), according to FollowTheMoney.org.

“We will have to do a lot of lobbying, and calls, and bipartisan support to get our Republican governor to sign it,” says Zink.

Muirhead expects other legislators to object to the bill’s costs. First are the administration fees: mailing out the certificates to every registered voter, determining candidates’ eligibility and enforcing the rules, maintaining the public database of every contribution, and publicizing and explaining the program to the public. Seattle spent about $1.3 million on these services in 2021, though Zink estimates that it would cost New Hampshire $500,000 annually.

Then there’s the campaign funding itself.

Assuming a field of a dozen candidates for executive council and two candidates for governor, Zink says the program will cost $6.2 million a year, or $12.4 million every election cycle. The bill includes four sources of funding: voluntary contributions, fines from campaign finance violations, interests that the fund accrues, and an earmark from the governor. Still, the exact funding mechanisms remain to be settled by lawmakers, Muirhead says.

Zink says that the current system costs taxpayers even more than the voter-owned alternative would. “Allowing private companies to finance our elections means we’re actually paying for policies that benefit those big donors.”

That argument may not be enough to persuade Republican politicians in New Hampshire to embrace an idea that’s only been tested in one of America’s most liberal cities.

But the idea may catch on in state governments elsewhere. If Minnesota passes the recently introduced Democracy for the People Act, its existing public financing system would shift from retroactively refunding campaign contributors, which few people know about or participate in, to proactively mailing two, $25 vouchers to all registered voters. These vouchers could then go to participating candidates in races for governor, state house and senate, secretary of state, and attorney general.

In Minnesota, unlike in New Hampshire, Democrats control the governorship and both chambers of the legislature. Even so, elected lawmakers may be reluctant to change the status quo.

Tellingly, in both Oakland and Seattle, voters were ultimately the ones who approved the program via ballot initiatives, not politicians. In that sense, these new bills are the most ambitious yet.

“I think it’s possible but not likely,” says Muirhead about his bill’s potential to pass the legislature. Muirhead sponsored a similar bill last year, which failed.

“We are taking the long view. We believe that we can renovate American democracy, but we have to do it the old fashioned way, by persuading people one-by-one,” he says. “That takes time.”