West Virginia Adds to Election Deniers’ Ongoing Takeover of State Politics

Senator Azinger’s rise fits in the status quo of a state where turnout is among the worst in the nation, though a package of more restrictive bills appears dead for the session.

Alex Burness | February 28, 2023

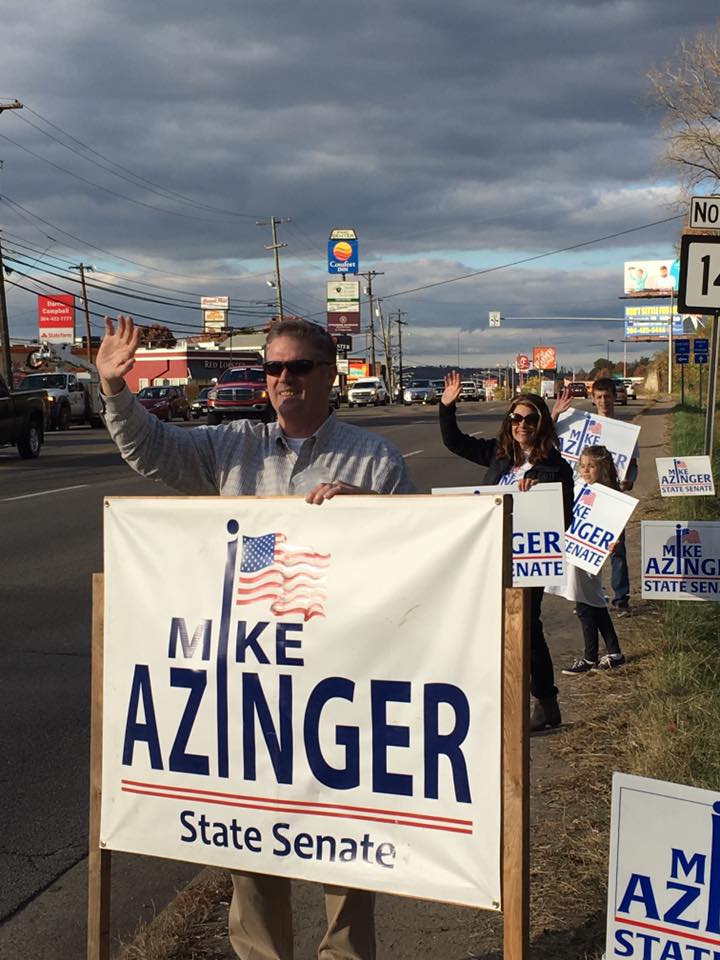

In January 2021, days after rallying outside the U.S. Capitol against legitimate presidential election results, West Virginia state Senator Mike Azinger said he hoped for an encore.

“(T)here’s a time where we all have to make a little bit of sacrifice. Our president called us to D.C.,” he told local news at the time. “It was inspiring to be there and I hope he calls us back.”

His loyalty to election denialism has not appeared to harm his political career; he was re-elected last fall after a tight Republican primary and a blowout general election, and, earlier this year, he was named chair of the Senate panel tasked with reviewing election policy.

Azinger is now one of several election deniers leading legislative committees on election law, including in the battleground states of Pennsylvania and Arizona. Others have been elected to lead state Republican parties in recent weeks.

This takeover of GOP infrastructure by candidates who spread false conspiracies about the 2020 election has continued even since their high-profile losses in the fall of 2022. But in West Virginia, voting rights advocates say Azinger’s appointment to the chamber’s elections subcommittee has barely registered as scandalous. Bolts found this is neither being covered in local media nor inspiring any particular outcry among fellow lawmakers or the general public.

Senator Mike Caputo, a Democrat on the elections subcommittee and the longest-tenured member of his party’s tiny Senate caucus, told Bolts, “The voters in Senator Azinger’s district elected him. They knew what his actions were. That’s just the way it is around here.”

Azinger’s heightened influence over election policy in his state fits neatly within the status quo in GOP-dominated West Virginia, where voting access is relatively restrictive, turnout is among the worst in the nation, and election deniers abound in the halls of power—and specifically in offices with real influence over election policy.

Republican Secretary of State Mac Warner, for example, appeared at a pro-“Stop the Steal” rally outside West Virginia’s capitol building in December 2020, and was quoted that day saying “it’s important” to keep Trump, who had already lost, in office. Warner is now running for governor.

Republican West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey signed on to a federal lawsuit seeking to overturn 2020 election results in key swing states won by President Joe Biden, and Warner endorsed the effort.

In January of 2021, both current West Virginia members of the U.S. House of Representatives, Republicans Alex Mooney and Carol Miller, voted to overturn 2020 presidential election results. Miller now faces a challenge from former Delegate Derrick Evans, who was imprisoned for three months in connection with storming the U.S. Capitol and last month announced he is running for Congress.

Eli Baumwell, interim director of the ACLU of West Virginia, is one of those playing defense against the state’s increasingly overwhelming GOP majority. He said it helps obscure Azinger’s appointment to the elections subcommittee that the “fringe” keeps shifting further right in West Virginia on a number of other political fronts, which are taking attention away from elections policy.

This session has brought a slew of anti-LGBTQ legislation, including House Bill 2007, which seeks to ban gender-affirming health care for West Virginia children. That policy passed the House by a vote of 84-10 and now sits in the Senate, which Republicans control. The House also passed a bill to give state funding to so-called “crisis pregnancy centers,” which discourage people from learning about or seeking abortion—something already near-totally banned in the state. Another bill, passed by the House this week, expands religious exemptions that critics worry will allow organizations to discriminate.

Amid that backdrop, it’s easy for a Senate subcommittee on election policy to go relatively unnoticed.

“We are continually dealing with more and more extreme politicians,” Baumwell told Bolts. “Mere attendance at January 6 isn’t even enough to understand how extreme some of these people are.”

Asked by Bolts about the reception to Azinger’s subcommittee chairmanship, Julie Archer, of West Virginia Citizens for Clean Elections, said, “I think people care, but also, when I think about some of the issues that some of our partners and allies are dealing with, … there’s just so much bad stuff, and people only have so much headspace for outrage.”

Azinger declined to be interviewed for this story.

Despite his participation in federal election subversion, plus newfound control of the subcommittee gavel, Azinger this year did not champion much in the way of legislation on elections, the state’s log shows.

The most controversial bill he has sponsored on this front, Senate Bill 516, would make it easier for dark-money political donors to donate in even higher amounts. The bill passed the Senate earlier this month, and currently sits in the House.

Other Republican lawmakers filed a pile of legislation that worried voting rights advocates, including bills to refer voter fraud cases to the (pro-election subversion) attorney general instead of to local prosecutors; to make state voter ID laws stricter; and to repeal the state’s automatic voter registration programs.

The package is all but dead—it would take an unexpected suspension of legislative rules by GOP leaders to revive it—with West Virginia’s legislature set to adjourn its session in less than two weeks. That’s in keeping with Republicans’ recent approach on elections policy: one nonpartisan evaluation of West Virginia’s 2022 session found the legislature was “restrained” on that front.

That Azinger and his party aren’t doing more to restrict the vote may be explained by the fact that Republicans are more likely to pass legislation in this area in states with closely contested general elections. West Virginia is hardly competitive; Trump beat Biden there by nearly 40 percentage points in 2020, and Republicans won nearly 90 percent of legislative seats in November.

Analyzing voting-access legislation around the country, researchers out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Spelman College found last year that, “among Republican-dominated states, the most active legislatures were those in which the 2020 presidential election was close.” They add, “legislative activity to expand or contract the electorate has often been motivated by electoral threat.”

Still, West Virginia generally ranks among the worst states for voting access, according to several nonpartisan groups. It does not provide no-excuse mail voting, ballot drop boxes or same-day registration. While it was an early adopter of automatic voter registration, implementation was repeatedly delayed, which Azinger supported, and voting rights advocates say the existing program is hardly effective.

According to the U.S. Elections Project, West Virginia voter turnout was fourth-lowest among states in 2020. Last November, West Virginia turnout was second-lowest in the country, at under 36 percent.

Azinger, in fact, may be more open to certain measures that might expand the state’s paltry electorate. Kenneth Matthews, a formerly incarcerated West Virginian working to restore voting rights for people released from state prisons on parole or probation, said Azinger at one time indicated he might support that policy, Senate Bill 38. Still, the Senate subcommittee on elections did not hold a vote on the bill, despite holding a hearing, before a legislative deadline.

“He applauded me for the efforts I’ve put in for my re-entry,” Matthews told Bolts, “and he said he’s glad I’m up here advocating and letting my voice be heard.”

Azinger has also not questioned the legitimacy of results within West Virginia. Around the country, election-denying Republicans are often more trusting of election systems, and open to liberalizing them, in their own jurisdictions. In rural Nevada, for example, a county elections chief this month told Bolts she is routinely hounded in her own community about election security—but that those questioning her usually are upset about other counties. And in Cochise County, Arizona—a hotbed of election-denier activity—Votebeat reported this month that the local elections chief “defended his own county’s election but couldn’t defend elections elsewhere in the state.”

Regarding the disconnect between Azinger’s more muted approach to elections in West Virginia and his proudly conspiratorial views on federal elections, Matthews notes that “it’s easier to see the weeds in your neighbor’s yard than your own, sometimes.”