Police Union Spreads Fear Over San Antonio Ballot Measure Decriminalizing Weed and Abortion

Prop A, on the May ballot, also calls for reducing low-level arrests and adding police oversight. But many local officials have followed the police union in attacking it.

Michael Barajas | April 19, 2023

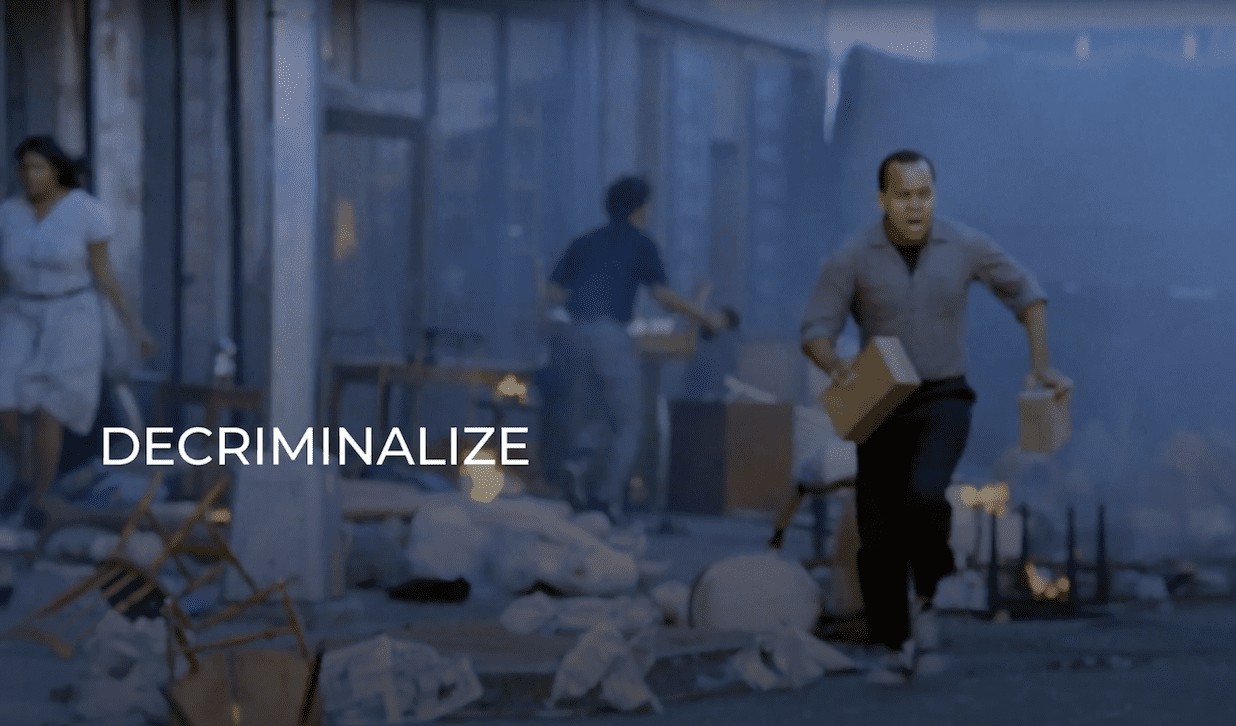

In one ad that the San Antonio Police Officers’ Association’s political action committee paid to splash across local televisions this spring, looters dart between street fires, masked gangs smash jewelry counters with hammers, red graffiti covers what appears to be a church, and men carrying bats gather in a dark street. “They want to keep criminals on the streets spreading urban decay,” a voiceover says, accompanied with yet more images of fire in the streets. The police union raised nearly $900,000 in the first three months of 2023 for such political advertising ahead of this year’s municipal elections.

The police union’s messaging, which has dominated San Antonio’s municipal elections this spring, wasn’t crafted to go after any particular mayoral or city council candidate, but rather to spread fear about Proposition A, a police reform charter amendment that local activists petitioned to get on the May 6 ballot.

The so-called Justice Charter is broad in scope because it was drafted by a coalition of San Antonio groups representing causes ranging from organized labor to reproductive justice, which wanted to build on reforms local organizers have been pushing for years. It would add a “Justice Policy” to the city charter that calls for ending citations and arrests for low-level marijuana possession, an idea city council members have long paid lip service to but failed to fully implement, as well as decriminalizing abortion, which the council already directed the city’s police to do last August after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision triggered Texas’s criminal abortion ban.

Prop A also calls for banning police chokeholds and no-knock warrants, both of which the San Antonio Police Department already has internal policies against. It would also direct police to prioritize citations over arrest and jail for people accused of certain low-level crimes, like theft below $750; this would codify and expand a cite-and-release policy that city and county law enforcement began implementing several years ago in the name of criminal justice reform.

Police union rhetoric has already convinced many people in power in San Antonio to oppose it. The city’s chambers of commerce established their own PAC last month to raise money from business interests to campaign against the ballot measure and amplify the police union’s talking points. Most of the candidates running for city council this year oppose the Justice Charter, and Mayor Ron Nirenberg, who is expected to sail to re-election later this year, urged people to vote no in early April despite having previously voiced support for much of what’s in it.

Their opposition raises major questions about Prop A’s future even if it were to pass, as some local officials also signaled they would not implement whole swaths of the measure. Prop A could also be challenged by Republican officials who dominate state government and love to pick fights in Texas’ more liberal cities, and anti-abortion activists who already sued to try to stop the measure from appearing on the May ballot are likely to keep agitating should it win.

Still, Ananda Tomas, founder and director of ACT 4 SA, the police reform group that led the effort to get the Justice Charter on the ballot, says that the intense opposition from the police union and the backtracking from the mayor highlight why local activists are pushing reforms through citizen-led ballot initiatives in the first place.

“I think not just here in Texas or San Antonio, but nationally, you’re seeing a lot more ballot initiatives as the people’s way of fighting back,” Tomas said. “When we have city or state leadership or even federal leadership that’s not moving with the people, then we’re going to take matters into our own hands, and that was the exact thinking behind this.”

Tomas’ group was born out of the massive protests and increased activism around police accountability that followed the murder of George Floyd in 2020. In 2021, Tomas and Act 4 SA gathered enough signatures to put a different measure on the ballot that sought to repeal police collective bargaining rights in San Antonio, which they had pitched as a means to begin addressing disciplinary procedures baked into the city’s police union contract that long shielded bad cops, sometimes even allowed awful ones back on the street, and yet had remained a third rail in local politics; officers the city’s police chief had tried to fire, but couldn’t, included a cop who berated and hurled racial slurs at a Black man while arresting him, an officer who was drinking on duty when he got into a gunfight and killed his girlfriend’s ex, and another who gave someone living on the street a sandwich with feces in it.

Proposition B, the 2021 ballot measure, failed by two percentage points. But last year, when the police union negotiated a new contract with the city, it quickly agreed to tweak its arbitration process in order to give the police chief more power over firing decisions—a departure from previous contract talks, when disciplinary rules were essentially off limits and yet still negotiations could drag on in years of acrimony and litigation with city officials.

“There was this whole narrative shift and power that the city was able to get in the negotiations by saying, ‘Hey, this is how close you guys came to losing your contract because people are so upset with how unaccountable it is,’” Tomas said. She thinks that the close vote over Prop B ratcheted up pressure to change the next contract.

The history of the San Antonio Police Officers’ Association is a case study in how police unions amass and wield power in local elections. It dove headfirst into local politics in the 1980s when it started publicly endorsing and opposing candidates, created a political action committee to bankroll their supporters, and established a formidable phone banking operation ahead of elections. People running for city council who wouldn’t commit to better pay and equipment for cops were smeared as anti-police and pro-crime, and by 1988 San Antonio police had paved the way for other police unions by negotiating one of the best wage and benefits packages in the nation.

San Antonio’s police union became notorious for its brash approach to local politics. One former San Antonio mayor wrote in a memoir about turning down police union money ahead of an election in the 1990s and receiving a gift basket with a dead rat in return. Politicians started calling the police union president at the time “The 44 Caliber Mouthpiece.” In 2013, after San Antonio’s then-city manager Sheryl Sculley established a task force to study reforming officers’ generous benefits because she thought they were threatening financial disaster for the city, one high-profile business leader on the benefits task force reported being tailed in his car by police officers. Sculley felt so aggrieved after battling the city’s public safety unions that she wound up writing a book chronicling the experience, which she titled “Greedy Bastards.”

With its fiery campaign against Prop A this year, the police union is again fighting back against what little reform it has been forced to accept in recent years. It has opposed the local cite-and-release program since Bexar County’s reform-minded district attorney spearheaded it after taking office four years ago, and which the Justice Charter aims to strengthen. The DA and his supporters say the program has saved the county $5.6 million in jail booking costs, helped alleviate overcrowding at the dangerous county lockup, and diverted thousands of people with petty, non-violent charges towards services.

Danny Diaz, president of San Antonio Police Officers’ Association, said in an interview with Bolts that cite-and-release policies have fueled an uptick in crime that was reported in San Antonio as well as cities across the country during the pandemic, even in places without such changes. But the city’s longtime police chief, William McManus, who does not support Prop A, has rejected that notion, and the DA’s office reports a recidivism, or re-offense, rate for defendants in the cite-and-release program of 9.6 percent compared 38 percent for people booked into the county jail.

Diaz insisted that the police union’s terrifying vision of what could happen if Prop A passes is “realistic”—that decriminalizing marijuana and abortion, in addition to codifying and expanding cite-and-release, would really allow dangerous criminals to escape consequences, force business across San Antonio to close, and plunge the city into chaos. But he also struggled when asked for evidence. How, as he argued, would local businesses and the community at large be worse off if more people accused of low-level theft got a citation and summons to appear in court instead of being hauled to jail? “I’ll put it as simply as I can,” Diaz said. “As children, we were all taught not to lie, cheat or steal. This proposition is basically telling people you can steal.”

Diaz, a former SWAT officer, also insisted that decriminalizing marijuana was a slippery slope but again sputtered general talking points about lawlessness when pressed. “If they’re not convicting or going to court or going to jail or giving fines for maijuana, they’re gonna turn around and do the same thing for theft on cite-and-release,” he said.

The police union’s ads and public statements over Prop A are also divorced from the reality of what’s actually in the ballot measure, claiming for instance that it seeks to decriminalize offenses like graffiti. But a cite-and-release program, which is meant to avoid people’s stay in jail, does not “decriminalize” since people would still be subject to criminal penalties.

Currently, it seems unlikely that any sweeping policy changes would immediately follow passage of the Justice Charter; San Antonio’s city attorney has already claimed that much of what’s in it is unenforceable. But part of what’s motivating the police union’s attacks on Prop A is the concern that a win would put pressure on future city councils to go further.

Diaz said he’s worried about more “activists” making it onto the council in the future and pushing to implement elements of the Justice Charter, especially if they see this year’s vote as a clear referendum by residents. He pointed to two progressive council members, elected in 2021, who voted against the union’s last contract for not going far enough on reforms to police discipline and oversight, and are now supporting the ballot measure.

The single element of the ballot measure that city officials have said they would implement has also riled the police union. It would create a new position at city hall, a Justice Director, someone without ties to law enforcement appointed by city council to review public safety policy, hold regular stakeholder meetings with communities that are heavily policed or have complaints about officers, and help mediate conflict between police and the public. The police union has, unsurprisingly, ridiculed the idea of appointing someone without policing experience to monitor them. But Prop A supporters have called it their best attempt to bolster independent oversight of the San Antonio Police Department, which is currently paper thin, even compared to dysfunctional oversight bodies in Texas’ other large cities.

Progressive organizers in other Texas cities have turned to local ballot measures to force reforms that local elected officials are refusing to consider or failing to fully implement. While most of those campaigns centered on marijuana, San Antonio’s is the most expansive and the first attempt by a Texas city to decriminalize abortion since the end of Roe.

But these initiatives are also a kind of end-run around an anemic and poorly organized Texas Democratic Party. One recently-formed statewide group, Ground Game Texas, has thrown itself into helping local organizers, including the coalition of San Antonio activists pushing Prop A, raise enough signatures to put reform measures on their local ballots.

Mike Siegel, who helped start Ground Game after twice running for a central Texas congressional seat on a progressive platform, said that the point of their work isn’t just to mobilize voters and build coalitions across the state, but also to force debates whenever people in power dig in their heels. “We’re starting fights,” Siegel said. “I think that’s the most important thing we’re doing, and I think that really is in some ways the core of Ground Game, kind of a catalyst, an allied group that partners with local organizations that have deep roots in the community.”

“Now we are head-to-head as a coalition with the anti-abortion lobby and the pro-cop lobby, which are two extremely formidable forces,” Siegel said.

Lingering questions over implementation, as well as fearmongering and misinformation by the police union, have clouded what’s actually at stake in San Antonio’s upcoming Justice Charter vote. But Yaneth Flores, policy director at the abortion rights group Avow Texas, insists that the threats pregnant people face in light of the state’s total abortion ban underscore the importance of taking a stand at the local level and codifying protections.

“I think that’s the right path for us, to say that as a city we are not buying into the fascist policies of the state,” Flores said. “I’m not exaggerating when I say that, because we are being robbed of having autonomy to make our own health care decisions.”

In addition to presenting it as a local bulwark against increasingly extreme anti-abortion laws at the state level, Prop A supporters hope that it sparks a deeper debate about what kind of criminal legal system San Antonio voters want. “At the end of the day, a really significant part of this ballot initiative has to do with a fundamental question of whether or not we as a community think that sending people to jail and having them sit there away from their families, away from their job away from their lives, is the best way to solve crime in our communities,” said Alejandra Lopez, president of the San Antonio Alliance, the local teachers union that backs the ballot measure.

Lopez said that part of the reason she has been personally working to pass the Justice Charter is because, as a teacher, she’s seen first hand how a criminal charge for pot or a stupid mistake like graffiti can derail a young person’s life and disrupt their family. She added that she’s disturbed by the inflammatory, streets-on-fire message by opponents. “The lies that are coming out of the opposition on this, we should all be troubled,” Lopez said. “We should be troubled deeply to our core about those tactics.”