How Will Philadelphia’s Next Mayor Tackle the Overdose Crisis?

Philadelphia has embraced policies to reduce deaths and promote safer drug use, but the city is now choosing a new mayor amid pushback against stronger harm reduction steps

Clare Boyle | May 15, 2023

When Melanie Beddis opens the Savage Sisters drop-in center in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood each weekday morning, there’s often a small crowd waiting at the door.

“People know that our shower list fills up quickly,” Beddis said. She says the drop in center is one of only two places unhoused people in Kensington can consistently take a shower. Visitors can also pick up safer use supplies like drug testing strips, get clean clothes and snacks, or simply hang out—lounging and chatting under the center’s neon purple lights and framed posters of the Philadelphia Eagles.

“It really is a community,” Beddis said. “If somebody spills their coffee, we have our regulars that will jump up and be like, ‘Just give me the mop. I’ll take care of it,’ you know what I mean?”

Kensington and the people who live, work, and use drugs in this small neighborhood on the city’s northeast side have drawn scrutiny in the run up to Philadelphia’s May 16 Democratic primary, which will likely decide the city’s next mayor.

In a tightly-run race animated by issues of crime and public safety, debates on substance use have honed in on Kensington’s opioid crisis and significant unhoused population. All five of the leading candidates say the city needs to end what’s widely described as an “open-air drug market” and increase policing in the neighborhood. At least two of these candidates also propose raising the police budget.

But local critics of a law enforcement-first approach to substance use worry that it may elevate overdose risks and perpetuate harm against people who use drugs, especially in Black and Latinx communities that already experience more policing. Instead, they hope the city’s next mayor will embrace harm reduction—a set of public health and social justice strategies aimed at protecting the dignity, autonomy, and rights of people who use drugs.

The city government’s response to substance use and the overdose crisis has thus far involved a complex patchwork of departments including police, public health, behavioral health, and homelessness services, and dozens of others, with guidance from the mayor’s office. Meanwhile, grassroots organizers in the city are locked in a years-long battle with state and federal officials to create a space for safer drug consumption. The proposal, championed by a nonprofit called Safehouse, has enjoyed some support from city officials since 2018 but has been delayed by lawsuits and now state legislation, even as similar sites have appeared in New York City.

The next mayor will oversee the city’s response to the ongoing overdose crisis and shape its policies, wielding powers like its budget proposals, executive orders, or appointing the police commissioner. The mayor’s position on an overdose prevention site may also make or break the proposal in light of some state politicians’ ongoing efforts to preempt the sites.

“The next mayor must take research about the effectiveness of harm reduction techniques seriously,” said Shoshana Aronowitz, an assistant professor at Penn Nursing who studies racial equity in substance use treatment and works with several harm reduction organizations across the city.

A skyrocketing overdose crisis

Over 1,200 Philadelphians died of accidental overdoses in 2021—the highest number ever recorded. The potent opioid fentanyl has found its way into stimulants such as methamphetamine and cocaine, and an increasingly unpredictable drug supply, plus a lack of adequate prevention resources are driving up overdose rates citywide, especially in its Black and Latinx communities. A 2021 city report recommended using the phrase “overdose crisis” rather than “opioid crisis” to more adequately capture this impact.

Much of Philadelphia’s current response infrastructure dates to 2017, when Mayor Jim Kenney convened a task force to determine how to “combat the opioid epidemic in Philadelphia.” The task force’s final report called for easier access to medication assisted treatment, in which doctors prescribe drugs called methadone and buprenorphine to relieve withdrawal symptoms and reduce the risk of overdose. It also advocated increasing access to naloxone, which can help reverse overdoses, expanding drug treatment court, and providing additional resources for housing and jobs training.

As fatal overdose rates continued to increase, however, Kenney declared an “opioid emergency” in Kensington and directed law enforcement to reduce “open-air drug use and sales.” Since then, the police have increased foot patrols in the neighborhood, seizing cash and drugs and making over 2,500 arrests in 2022 alone.

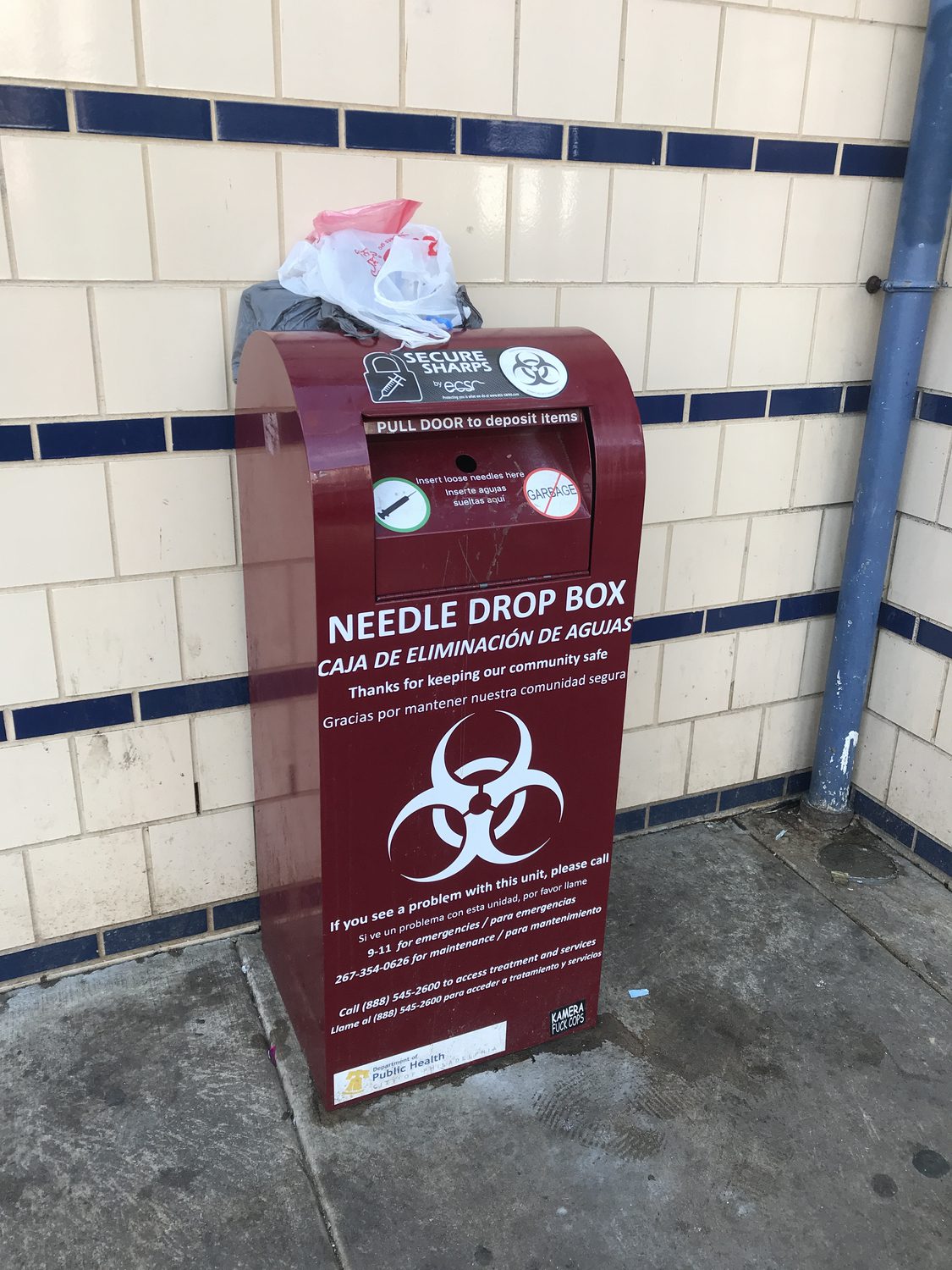

Since 2020, a harm reduction program within the city’s department of public health has been distributing naloxone and fentanyl test strips through street-based outreach and training Philadelphians on how to spot and reverse overdoses. The city also funds some of the work of a Kensington-based harm reduction nonprofit offering syringe exchanges. And the department of health has committed to reducing overdoses that involve stimulants 20 percent by the end of 2023, according to its strategic plan.

All five leading mayoral candidates have expressed some vision of treatment for people who use drugs, but Rebecca Rhynhart and Helen Gym’s proposals most resemble this existing plan. Both have expressed support for medication assisted treatment.

A spokesperson for Gym’s campaign told Bolts the candidate would “improve prevention, [drug] testing, and treatment outreach,” especially in “underserved Black communities in North, Southwest, and West Philadelphia, where overdose rates are rising.”

Candidate Jeff Brown has advocated for drug treatment through the criminal legal system.

“Drug court [is] a very effective way to have a good outcome, because you monitor their substance use. If they fall off the wagon, they have a choice. Do you want to go to jail for your crimes, or do you want to go back to treatment?” he said at a recent candidate forum about public health.

But Aronowitz warns that not all treatment options are created equal. “We know what doesn’t work,” Aronowitz said, “And that is expecting people to just quit cold turkey and be fine, because we know that that’s associated with extreme overdose risk.”

“When a politician says we need more access to treatment, that’s not enough,”she continued. “We need to know if they’re going to fund the things that work and defund the things that not only don’t work but are potentially harmful.”

The battle over Safehouse

Advocates doing harm reduction work in Philadelphia are pushing the city government to expand its focus on keeping people alive, beyond offering treatment, and they have fought to establish an overdose prevention site in Philadelphia, an effort the city government nominally supports. Such sites, also known as safe drug consumption sites, are places people can use pre-obtained drugs more safely, in the presence of staff trained to spot and reverse overdoses.

As of July 2022, more than 120 overdose prevention sites existed in ten countries across the world, and no fatal overdoses had ever taken place in one. But they remain controversial in the United States. So far, only two such sites exist in the country, both in New York City, where staff have reversed more than 700 overdoses in the less than two years since they were created. Rhode Island legalized the creation of a pilot site in summer 2021 and is set to open one in early 2024. California governor Gavin Newsom last year killed legislation that would have allowed San Francisco, Oakland, and Los Angeles to establish their own sites.

In Philadelphia, efforts to open such a site have been caught for years in a protracted battle pitting harm reduction advocates and some city officials like DA Larry Krasner against the U.S. Justice Department, some state politicians, and opponents in law enforcement, business, and residential communities across the city.

The struggle dates to a recommendation from Mayor Kenney’s 2017 opioid crisis task force to explore creating a space for safe consumption. In 2018, a nonprofit called Safehouse launched with the aim of opening a site in the city. But soon after, a U.S. Attorney appointed by President Donald Trump sued Safehouse invoking a federal law which prohibits “maintaining drug-involved premises” where criminalized drugs are manufactured, distributed, or used.

In February 2020, the federal judge’s ruling in Safehouse’s favor led the group’s leaders to announce the site’s imminent opening in South Philadelphia. But after vehement opposition from neighbors, the plans folded in just two days. In 2021, a federal appeals court reversed the ruling that had cleared the way for Safehouse to open, relaunching the legal battle.

The plan remains uncertain at this time. Settlement talks between Safehouse and the U.S. Justice Department have been ongoing for over a year. Local opposition exploded last month, when a group including the police union and business associations filed a petition to step in as party plaintiffs in the lawsuit, fearing that the Biden Administration would reverse its position.

Opponents to the site scored a decisive win earlier this month when Pennsylvania’s state Senate voted to ban overdose prevention sites anywhere in the state on a bipartisan 41-9 vote.

The bill was sponsored by Democratic Senator Christine Tartaglione, whose district includes parts of Kensington. She told The Philadelphia Inquirer that she opposes “prolonging and allowing a system of state-sponsored addiction in Pennsylvania.”

The bill now sits in the state House’s Judiciary Committee. If it passed the chamber, it would move on to Governor Josh Shapiro, a Democrat who has indicated he opposes safe consumption sites.

Meanwhile, five Philadelphia city council members introduced a local bill on May 11 that would prevent an overdose prevention site from being created anywhere in their districts, an area amounting to about half the city. Councilmember Quetcy Lozada, whose district includes Kensington, led the effort, saying that such a site would only worsen the neighborhood’s struggles with drug consumption.

“We cannot continue to allow them to find ways where they can continue to remain in the same cycle,” she told Inquirer. The bill would still need to get a committee hearing and be voted on by the entire city council—a process that may not happen before the council’s summer recess beginning in July—before going to the mayor to be signed.

In public statements and court filings, Kenney’s administration has supported efforts to open an overdose prevention site, and remains supportive even in light of the new city and statewide bills. Whether the next mayor supports Safehouse would likely be critical to its chances given that the proposal is assailed from many quarters.

Among mayoral candidates, Helen Gym, a former teacher and city council member embraced by activists on the left, is the only one to have directly stated support for an overdose prevention site, though she did so before the protracted legal battle over Safehouse.

“[Safe injection sites] are among the most promising new approaches to come forward while we work to end the opioid crisis. I support establishing one in Philadelphia,” Gym said in 2017. Her statement at the time added momentum for the proposal by giving it a prominent supporter on the city council. Gym has recently offered more circumspect answers in public comments, and did not respond to Bolts’ question about whether she currently supports opening a site in the city.

Another leading candidate, former city controller Rebecca Rhynhart, expressed measured support for the proposal. “I won’t take a tool that experts say saves lives off the table,” she told Bolts. “But I would not put a safe injection site in any neighborhood that does not want one.”

“I think that the debate over safe injection sites in Philadelphia has clouded the bigger issue which is what is the comprehensive plan for dealing with the opioid crisis in our city,” she added.

Three other major contenders—real estate mogul and former councilor Allan Domb, grocery store magnate Jeff Brown, and former councilor Cherelle Parker—all oppose the sites. Parker has been a strident opponent since Safehouse’s efforts to open a site in early 2020, when she participated in the city council’s mobilization against the opening.

“We should not be participating in a ‘I know what’s best for you’ decision making where we use safe injection sites as solutions,” Parker said in a debate on April 18.

Policing a public health crisis

The role of policing has proved broadly divisive in the mayoral primary, and yet the five leading candidates support increasing police presence on the ground in Kensington, distancing themselves from advocates who worry it would exacerbate criminalization.

Gym and Rhynhart each said they would do so by reallocating existing police funds to prioritize Kensington, while increasing the police budget overall is a central component of both Domb and Parker’s platforms.

A spokesperson for Gym’s campaign told Bolts the candidate will take a “public health and resident-focused, community-led response,” mentioning a focus on neighborhood improvements, trauma support, and mobile crisis units, but did not detail how increased policing will fit in.

Rhynhart’s campaign website states that she will attempt to disrupt public drug use by focusing on dealers, with a mix of warnings for “non-violent dealers” and arrests for “those committing violent acts.”

Sheila Vakharia, who helps lead research at the Drug Policy Alliance, warns that the line between people using drugs and people selling drugs is much more fluid.

“There’s this idea that there is this big bad demon-ish seller and this poor victim user and oftentimes the seller is racialized. The victim is also racialized, but differently,” Vakharia said. “And oftentimes all of this can create heroes and villains.”

To both Aronowitz and Beddis of Savage Sisters, ending the overdose crisis requires a solution beyond what has been proposed by any candidate in the Philadelphia mayor’s race: addressing the toxicity of the criminalized drug market. They argue instead for access to a safe supply of criminalized drugs in a way that clinical and community-led programs have modeled across Europe and Canada, but which has not been piloted in the U.S.

“The way we regulate alcohol is safe supply,” Aronowitz said. “We make sure it’s not poison, and that when you take a drink, you can reliably know how much alcohol is in it.”

But even if those goals are still far off, at the very least, they say, the city government should meet communities impacted by the overdose crisis with resources and care—not criminalization.

“Our friends have necrotic limbs. Can’t access treatment. Can’t access housing. Can’t access compassionate pain management. Can’t even get a shower,” Savage Sisters’ founder and executive director Sarah Laurel wrote on LinkedIn last month.

“It’s time we respond to this public health crisis accordingly.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Pennsylvania Votes

Bolts is closely covering the ramifications of Pennsylvania‘s 2023 elections for voting rights and criminal justice.

Explore our coverage of the elections in the run-up to the May 16 primaries.