Republicans Escalate Attacks on Election Administration in Texas’ Largest County

Voting rights groups worry that two GOP bills will create a “feedback loop of problems” in Harris County, tripping up election officials to then subject them to new investigatory powers.

Michael Barajas | June 2, 2023

Update: Governor Greg Abbott signed Senate Bill 1750 and SB 1933 into law on June 18, 2023.

Trudy Hancock became the first elections administrator in Robertson County, a rural area northwest of Houston, after the county ditched their old model of running elections in 2005.

Until then, a county clerk was in charge of the voting process and a tax assessor-collector was responsible for voter registration; officials then unified those duties under an elections office managed by someone they would appoint—eventually Hancock, a longtime elections worker. Officials in nearby Brazos County, home to one of the nation’s largest universities, plucked Hancock to run their new elections office in 2016, after they too switched to the new unified system.

Hancock, who still runs elections in Brazos County and is now president of the Texas Association of Elections Administrators, says voters were sometimes confused by the old split system. “If you were a county clerk and their question had to do with voter registration, then you had to send them somewhere else, and lots of times those offices aren’t even in the same buildings,” Hancock told Bolts.

Counties across Texas, including most of the state’s largest urban centers, have adopted that new unified model for running elections over the past two decades as a way to streamline operations and better serve voters. Besides increasing efficiency, some local officials say this also erases a relic of the Jim Crow era; Texas tax assessors took on voter registration in the early 20th century because they also collected poll taxes. In 2020, Harris County, the state’s most populous and home to Houston, also switched to that unified system for running elections.

But Republicans pushed a bill through the legislature last week that will force Harris County to turn back to the old model for running elections. Senate Bill 1750, which abolishes the Harris County elections administrator position and returns those responsibilities to the county clerk and tax assessor-collector, is one of two bills specifically targeting election administration in Harris County that passed the GOP-dominated legislature and are now heading to Governor Greg Abbott, who is expected to sign them.

The second bill, SB 1933, grants the secretary of state’s office new powers to investigate complaints of “irregularities” in Harris County elections, and ultimately to petition to remove the local officials overseeing elections.

The two bills are an escalation in GOP attacks on election administration in Texas’ largest county, which has become an increasingly reliable Democratic bulwark against a deep-red state government. During the last session, in 2021, the legislature passed a sweeping set of restrictions aimed at some of the boldest initiatives that Harris County elections officials implemented to expand safe voting options during the pandemic, like drive-thru and around-the-clock voting, which are now banned under state law.

The bills that passed this session, however, differ from the last in that they explicitly target Harris County: The measure forcing a return to the split system for running elections only applies there, as does the bill granting the secretary of state new investigatory powers. While neither bill specifically names Harris County, SB 1750 and SB 1933 were tailored to only apply to counties of more than 3.5 million and 4 million residents, respectively, a threshold that only Harris County meets.

Bolts reported after last year’s midterm elections that Texas Republicans had seized on ballot shortages Harris County voters encountered at a handful of polling places to push for state intervention and more policing of elections. Nearly two dozen Harris County GOP candidates have pointed to those problems to challenge their losses, claiming the ballot shortages led to thousands of voters being turned away in Republican-leaning precincts. Reporting by the Houston Chronicle, however, has largely debunked that narrative, showing that the ballot shortages weren’t widespread (affecting about 20 of 782 polling places in the county) and impacted Democratic and Republican areas evenly.

Harris County elections administrator Cliff Tatum, whom the county hired barely two months before early voting started in the November election, issued a report in January saying the problems during the midterms pointed to the “immediate need of upgrades or replacements” in the elections office. Tatum has said his office implemented several changes after the midterms to respond to those problems, from hiring more helpline operators to respond to problems at polling places to implementing a new system for tracking requests from election judges.

In a statement to Bolts, Tatum stressed how the new legislation would reshuffle elections administration ahead of another important election; Democrats tried but failed to get Republicans to amend the effective date for SB 1750 until after Nov. 7, when Houston will elect its next mayor. Tatum said the law is now set to force changes to election administration on Sept. 1, 39 days ahead of the voter registration deadline and 52 days out from the first day of early voting. “We fear this time frame will not be adequate for such a substantial change in administration, and that Harris County voters and election workers may be the ones to pay the price,” Tatum said.

Voting rights advocates worry that the bills targeting Harris County will set up whoever runs elections there next to fail, or at least trigger the new oversight powers by the state established under SB 1933. Harris County also saw problems under its earlier split system of administering elections, with past clerks accused of bungling elections and tax assessor-collectors wrongly suspending voter registrations. The oversight bill, which allows for the secretary of state’s office to investigate and petition to remove election officials, would also go into effect in September if signed.

Katya Ehresman, voting rights program director with Common Cause Texas, said that both Harris County election bills “create a feedback loop of problems down the road.”

“I don’t think it’s unreasonable that we can expect a huge turnout this November because of the multi millions of dollars that are probably going to be spent in this mayoral race, and the conditions for the elections are completely changing right before it,” Ehresman told Bolts. “That’s something that lawmakers were cognizant of, because they used that as a reason to blame the elections administrator for the problems we saw during the last election. And yet now the legislature is just replicating those conditions, and they will be uniquely to blame for any problems voters encounter because of it.”

Harris County officials have already vowed to fight the bills in court. Harris County’s clerk and tax-assessor collector, both elected Democrats, declined to comment on any plans to reassume election duties, with representatives of both offices telling Bolts they’d issue statements if and when Abbott signs the legislation.

Hancock told Bolts she worries that, even if the bill expanding investigations is limited to Harris County, it could erode the relationship between the office and local elections workers. Currently, the secretary of state is largely an advisory role to assist local election officials. “If you’re having a problem, you’ll be less likely to call and talk to someone about that problem if you’re worried they’re going to come back and later feel the need to assert their role as oversight,” Hancock said.

“We’re worried it will have a chilling effect with the relationship that we currently have with the SOS,” she added.

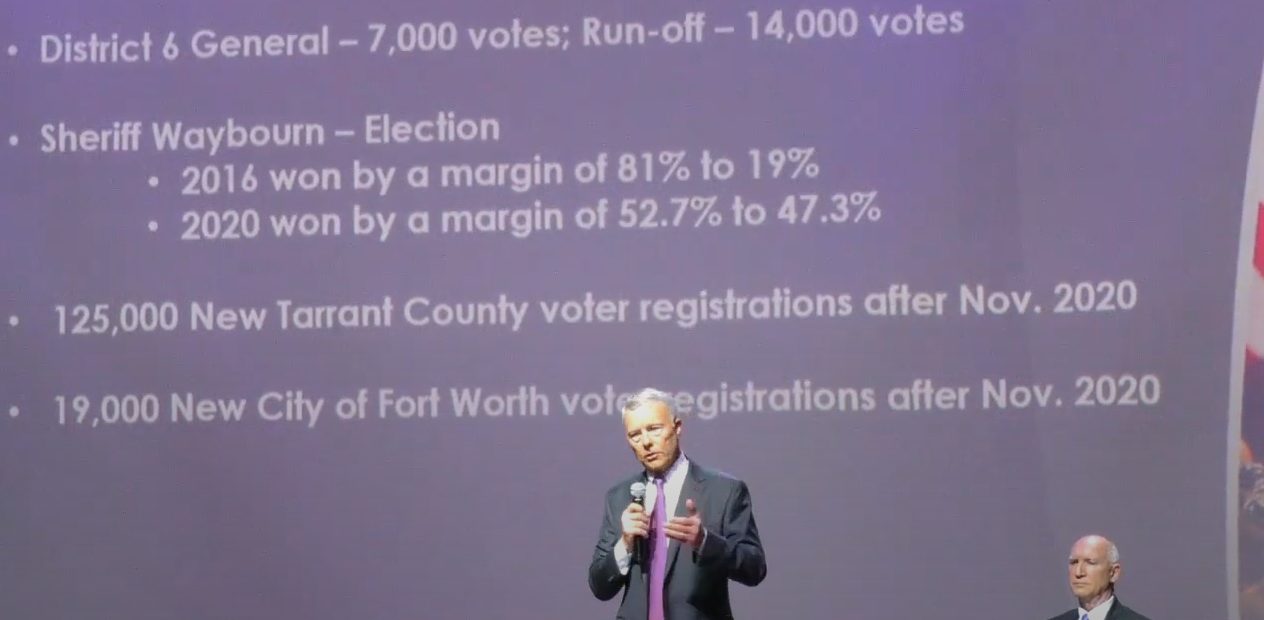

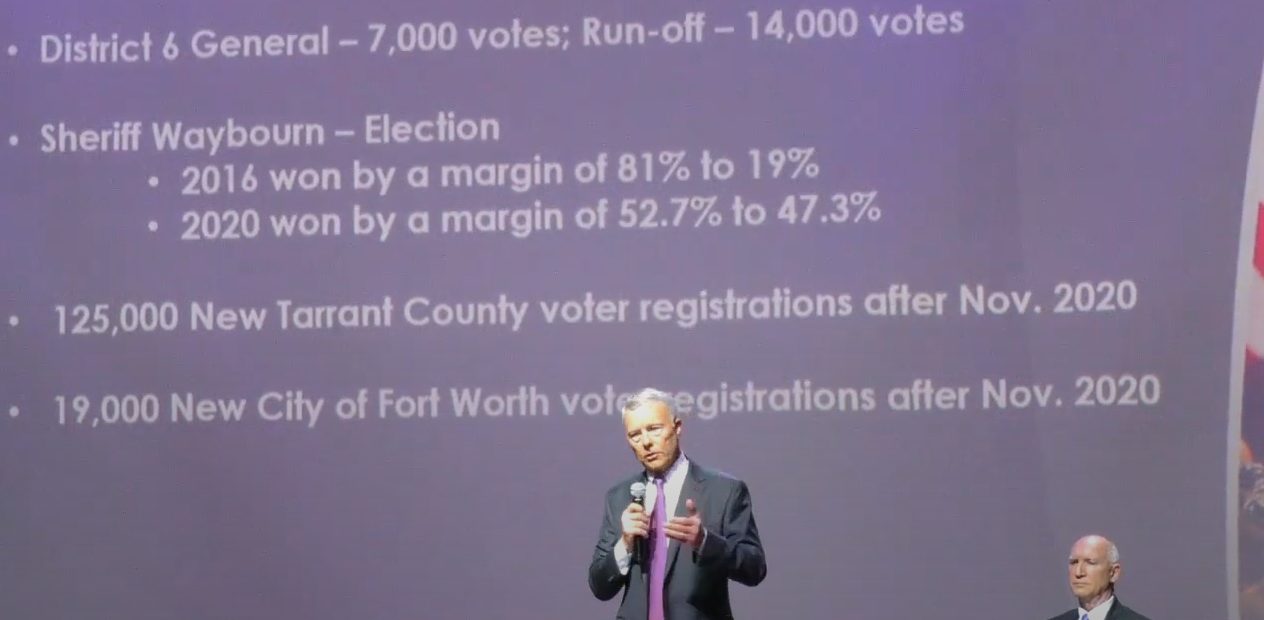

Republicans have also targeted election administrators in other parts of the state, most notably by ramping up policing around elections in Tarrant County, home to Fort Worth and the Texas GOP’s last urban stronghold; their actions led the county’s election administrator to resign in April.

Ehresman warns that the GOP meddling won’t stop there. She pointed to a host of other proposals—from ending countywide polling to giving the secretary of state even greater oversight powers—that failed in this year’s regular session but right-wing officials are already trying to revive.

“This was an unprecedented move by the legislature to use the entire weight of their branch of government to eliminate an office, effectively fire one man, and target one specific county,” Ehresman said. “So I don’t think it’s unreasonable now that the legislature has gone this far for one county, that they won’t do it for other large urban counties.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Our weekly newsletter on the local politics of criminal justice and voting rights