Melinda Katz Once Faced Off Against DSA. Now It’s New York’s Police Lobby.

Since barely beating a leftist candidate to become Queens DA in 2019, Katz has stuck to a conventional approach to the office. Still, she has drawn a challenge from former cop George Grasso in the primary next week.

Maggie Duffy | June 20, 2023

This article is produced as a collaboration between Bolts and Mother Jones.

On June 25, 2019, in a nightclub in Woodside, Queens, public defender Tiffany Cabán claimed election night victory as the borough’s newest District Attorney. Backed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Cabán—a queer Latina woman from Richmond Hill, Queens, who ran on ending mass incarceration and the war on drugs—beamed as the crowd shouted “DSA!” In theory, it was a left-wing victory: Cabán had run among a slate of seven candidates, including Queens Borough President Melinda Katz, and won. But just days later, outstanding provisional and absentee ballots changed the picture. After the final tally, Katz, a moderate and the Democratic party’s favored choice, led by a mere 60 votes. Cabán conceded.

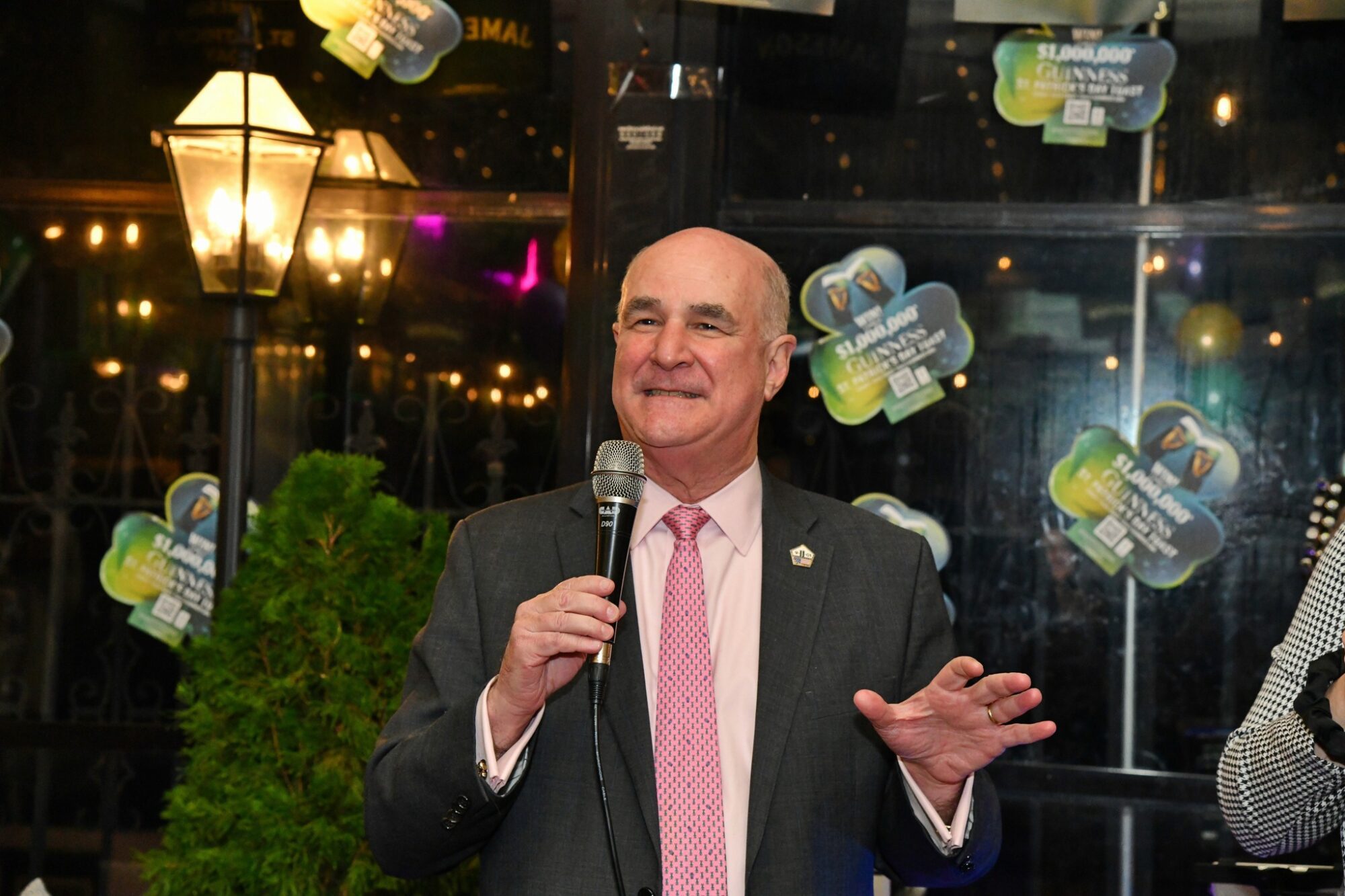

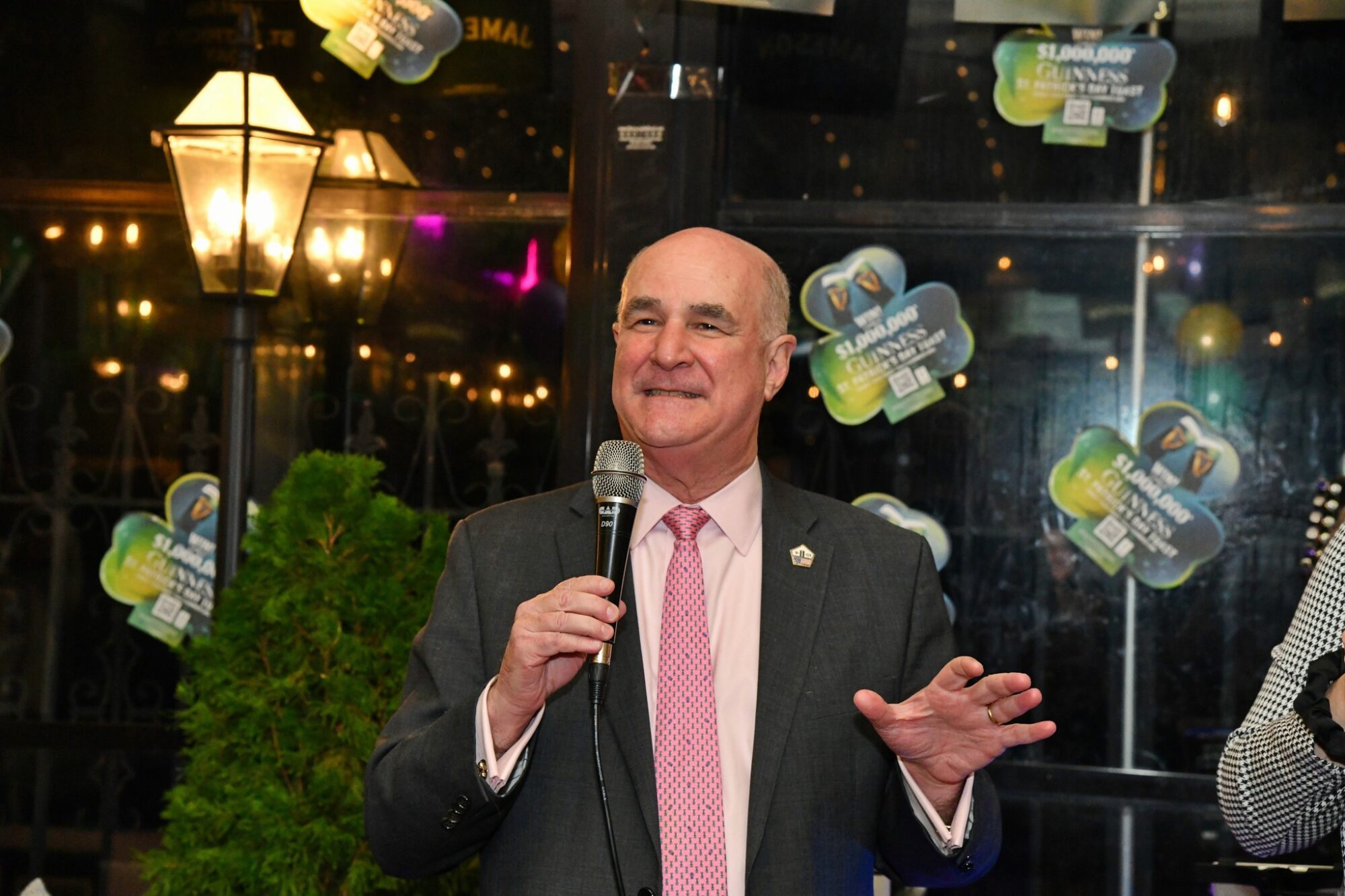

Almost exactly four years later, on June 27, Katz will try to keep her office. This time, her leading opponent in the Democratic primary is a candidate who is nothing like Cabán. Katz faces George Grasso, a former NYPD cop and an administrative judge for criminal matters for Queens Supreme Court who decided to leave the bench more than two years early because he “could no longer keep [his] mouth shut” about the state of the city’s public safety, he told Mother Jones and Bolts.

The shift in debate in this primary race is the latest example of a broader transformation in the politics of crime and public safety in New York. Instead of a challenge from a leftist like Cabán, the insurgent candidate is Grasso: a man who gleefully calls himself the “anti-Krasner,” a reference to Philadelphia’s progressive district attorney. Grasso is openly advocating for a return to law-and-order approach to policing.

His entrance into a Democratic primary is indicative of a move to the right foreshadowed by New York’s Democratic leaders. Mayor Eric Adams and Governor Kathy Hochul have touted tough-on-crime policies, doubling down on critiques of bail reform, and moving away from decarceral solutions. The contours of the Queen’s race is part of a larger national narrative, according to experts: In Democratic cities, like San Francisco and Boston, tough-on-crime rhetoric has become a norm again. Data-driven critiques, and reevaluations of criminal justice policy, have less sway—some Democrats, instead, want to return to the politics of law-and-order.

Grasso started out as a “foot cop” in southeast Queens in 1979. He rose to first deputy police commissioner of the NYPD, a position he held for almost a decade, before, most recently, taking the bench as an administrative judge in the Queens Supreme Court. Often, Grasso mentions his tenure with former New York City police commissioner Bill Bratton, who has endorsed him, as core to his beliefs about policing. He says his priority is to return the DA’s office to the quality-of-life enforcement Bratton embraced—criminalizing lesser offenses such as defacing property and fare evasion that “create conditions conducive to” increased crime and violence. (Grasso was part of the Giuliani-era team that designed the first quality of life strategy for Commissioner Bratton.)

In conversation with Mother Jones and Bolts, Grasso mentions specifically taking on fare evasion. The Friday following the death of Jordan Neely—an unhoused Black New Yorker who was choked to death by another passenger on a subway train car—Grasso took to Twitter, not to express outrage at Neely’s public killing, but to criticize the NYPD for ending warrant checks for violating transit laws, a policy that ended due to overwhelmingly targeting houseless New Yorkers. “WHAT!!!! This is the misguided policy that led directly to Mr. Neely’s death and Mr. Penny’s arrest!” he wrote.

Grasso told Mother Jones and Bolts that if the law had been enforced properly, Neely would have likely have ended up back on Rikers Island. “Maybe they would’ve hooked him up with some kind of mental healthcare or something,” he said. “We know one thing for sure, he would be alive today.” (This year, three people have died at Rikers. Last year was the deadliest in a quarter century, Gothamist reported, with 19 deaths at the jail; six are reported to have been suicides.)

While Grasso extols broken windows policing, he says he wants to prioritize mental health as DA, creating the office’s first mental health bureau and turning Rikers Island into a Bellevue Hospital satellite to treat the majority of the incarcerated population at Rikers who struggle with mental illness. During his judicial tenure Grasso championed alternatives to incarceration, creating diversion programs for teens in partnership with the Center for Court Innovation.

“I really hate the fact that people say, ‘Oh, Grasso’s coming in from the right.’ I’m telling you, I do not consider myself right-wing in any way, shape, or form,” he said. “MAGA makes me wanna throw up.”

Despite that, Grasso has created an independent “Public Safety” party line on the General Election ballot in November to ensure all Queens voters, including Republicans, can vote for him. He’s spoken at both Central Queens and Queens Village Republican clubs in the past few months. He says it was because requests to speak at Queens Democratic clubs were denied.

Grasso’s rhetoric is a “caricature of a Republican throwback,” according to Anthony C. Thompson, a professor of clinical law emeritus of law at New York University and founder of the faculty’s Center on Race, Inequality and the Law. “If we look at history, Katz tacked to the left rhetorically to respond to her opponent [in 2019], so it is a legitimate question to say, ‘Will she tack to the right to respond to Grasso?”

The incumbent Katz is once again backed by the New York Democratic Party stalwarts. She has received $12,500 in donations from Jay Jacobs since 2022, the head of the New York State Democratic Party, and has been endorsed by state officials including U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer and Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez. She has led a fairly moderate reelection campaign focused on straddling the line—attempting to triangulate between reform and harsher crackdowns on crime. Katz has defended her record of getting guns off the street and curtailing retail theft, while also making structural changes to the criminal legal system called for by some progressives.

In May, Katz shared her campaign ad, and tweeted that it is “appropriately titled, ‘Promise’”—a reference to pledges she made to voters when she took office in 2020. Katz has fulfilled some of them. She notably created a wrongful conviction unit and a hate crimes bureau within the DA’s office.

But Katz has been shaky on other reforms. In her 2019 campaign, Katz vowed not to prosecute low-level marijuana charges. In 2021, she did dismiss thousands of marijuana-related offenses, but this April her office began cracking down on unlicensed cannabis vendors. On sex-work cases, Katz said she would work to implement the controversial Nordic model which prosecutes clients and sex traffickers, not sex workers, but according to Documented, Queens still maintains the highest rates of prosecution for prostitution arrests in the city.

Katz has maintained a conventional approach to office that follows that of a politician responding to pressure rather than a prosecutor committed to fixing problems, according to Thompson. He points out her decision to start a conviction integrity unit, for example. “She didn’t say, ‘When we reversed 99 cases because of conviction integrity problems, we then looked at the prosecutors who tried those cases and had them engage in training or fire them,’” Thompson says. “It’s been very much a political response. It sounds like what a state assembly person would respond, not what a thoughtful district attorney who’s trying to change her office would respond.”

Most notably, Katz has waffled in her views on bail reform. At the start of her last campaign, in December 2018, she said she would no longer seek cash bail for misdemeanors and advocate for broader state legislation that would do the same. Six months later in a June candidate debate, Katz said, “under my administration, there will be no cash bail.” Then, one week after taking office in 2020, an assistant district attorney in Katz’s office set bail for a man charged with stealing a cellphone at $50,000, breaking her initial reform pledge. (When NY1’s Erroll Louis questioned Katz about reneging, she said she believed cash bail was unfair “deep in [her] heart” but that Queens was not ready to eliminate it.)

Bail reform has stood in for broader discussions about crime in New York in the past three years since it went into effect. Adams and Hochul have both pointed to the 2019 bail reform law—which sought to end cash bail for a wide array of misdemeanors and non-violent felonies to prevent jail time for low-income defendants—as a reason for spiking crime.

This spring, New York’s state legislature, with Hochul’s blessing, passed a budget that rolled back some of the most significant reforms of the 2019 bail law. The changes eliminated the provision that judges needed to use the “least restrictive” means to ensure defendants return to court. Now, judges are allowed to set any conditions they deem necessary—including setting cash bail, which, advocates have warned, will lead to more pretrial incarceration.

Both Grasso and Katz have supported this rollback, and in fact have each argued for a further revision to bail reform, to include a “dangerousness standard” that would allow judges to consider defendants’ past conviction or other more nebulous factors in order to detain them pretrial. Hochul has argued against implementing dangerousness calling it “subjective” and “determined by the color of [defendants’] skin and perception of dangerousness,” but critics have said her new revision is equally as arbitrary and biased. (It ultimately was not included in the budget that passed.)

On May 5, Katz joined Adams and Hochul at an event to sign the controversial bail reform changes into law. Katz called it a “welcome amendment” in a statement. But Grasso believes it doesn’t go far enough. He has said the fact of Katz’s attendance at the event proves she isn’t “serious” about setting a true dangerousness standard for defendants.

Queens had the second largest number of arrests for misdemeanors, according to recent data from New York City’s Criminal Justice Agency, among the five boroughs. More than 17,000 people were arrested in Queens on low-level offenses, many of whom, if unable to post bail, could end up in Rikers for months at a time.

While the 2019 race moved the frame of what the new DA could do in office and how she could use her discretion wisely for safety and justice, Katz is hardly seen as a reformer, says Insha Rahman, the vice president for advocacy and partnerships for the Vera Institute of Justice. “Some of her policies are indeed reform oriented,” Rahman says. “[But] Katz has in general been less reform minded in her first term in office, than say, certainly Eric Gonzalez in Brooklyn, or Alvin Bragg in Manhattan.”

In other U.S. cities, Rahman says, there’s more appetite among voters for solutions to crime that don’t resort to failed models of justice. Just last month, in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, home to Pittsburgh, voters elected public defender Matt Dugan over the incumbent Steve Zappala in the Democratic primary. But in DA races across New York state there are far fewer self-professed reformers on the ballot than four years ago. In the Bronx, defense attorney Tess Cohen is challenging incumbent Darcel Clark on a progressive platform, but in Queens, progressives have largely haven’t weighed in on the contest between Katz and Grasso. (Cabán did not respond to a request for an interview.)

One exception has been progressive city councilmember Shekar Krishnan, who publicly supported Tiffany Cabán in 2019. He wrote that he has not “always seen eye to eye” with Katz, but still commended her for her efforts in a June QNS editorial where he endorsed her run against “dubious opponents.”

As with most off-year elections, turnout will determine the outcome. In the 2019 primaries, only 11.9 percent of Queens voters showed up to the polls. It is the immigrant borough, with 46 percent of residents who were born outside of the country.

One difficulty in projecting the results could be the presence on the ballot of Devian Daniels, a former public defender, who entered the race in mid-April. While Daniels is running to reform the office with a focus on decriminalizing poverty and ending mass incarceration, she does not have an active campaign, with any contributions or endorsements on record—with the exception of submitting signatures for ballot placement. Her candidacy was not approved by the New York City Bar Association. Daniels has also been tied to Hiram Monserrate, the former New York legislator convicted of federal corruption charges for stealing city council funds and for assaulting his girlfriend. (Daniels did not respond in time for requests for comment.)

Still, Katz is expected to prevail. Neither Rahman nor Thompson believe Grasso will win the primary. Yet both worry about how progressives might hold Katz’ office accountable.

“I think the danger is that Katz will misinterpret a victory as a signal that she doesn’t need to do anything differently, ” Thompson tells Mother Jones and Bolts. “The great challenge around people who really wanna see true racial equity in the criminal legal system and true reform is: How do we continue to keep elected officials’ feet to the fire?”