“An Issue No One Can See”: Watchdogs Fault D.C. for Ongoing Solitary Confinement

D.C. Jail authorities claim to no longer use solitary confinement, but still isolate people with mental health crises in "safe cells." A bill introduced in September seeks to limit this practice.

Kaila Philo | February 20, 2024

Mary Cheh wasn’t well-versed in solitary confinement before 2015. As a law professor, she’d focused mostly on constitutional law and criminal procedure.

Cheh, who was a Washington D.C. City Council member at the time, says a tour she took of the D.C. Jail that summer that led her to introduce the Inmate Segregation Reduction Act of 2015, which attempted to limit solitary confinement throughout the District’s correctional facilities.

In December of that year, advocates with the National Religious Campaign Against Torture erected a full-size replica of a solitary confinement cell in the Foundry United Methodist Church in Northwest D.C. to raise awareness for Cheh’s bill ahead of a council vote. Cheh, who visited the church one Sunday that month to speak about the proposed reforms, says the image of the cell’s cramped confines has stuck with her ever since.

“It really took the activism of groups to point out to me the ills—the absolute horror, even—of solitary confinement,” she told Bolts.

But Cheh’s bill never made it to a vote. In fact it never made it out of the judiciary committee where it was first referred. Cheh tried twice more to pass laws reducing solitary confinement before leaving the council in 2022, but those proposals died as well.

Then in September 2023, D.C. Council member Brianne Nadeau took up the baton by introducing the ERASE (Eliminating Restrictive and Segregated Enclosure) Solitary Confinement Act. Nadeau’s office worked with the local chapter of Unlock the Box, a coalitional advocacy campaign seeking to end solitary confinement nationwide, in drafting the language of the bill. It aims to comprehensively ban solitary practices in the D.C. Department of Corrections’ facilities, but it remains to be seen whether Nadeau and her co-sponsors on the Council will be able to generate the political will to get it passed this time.

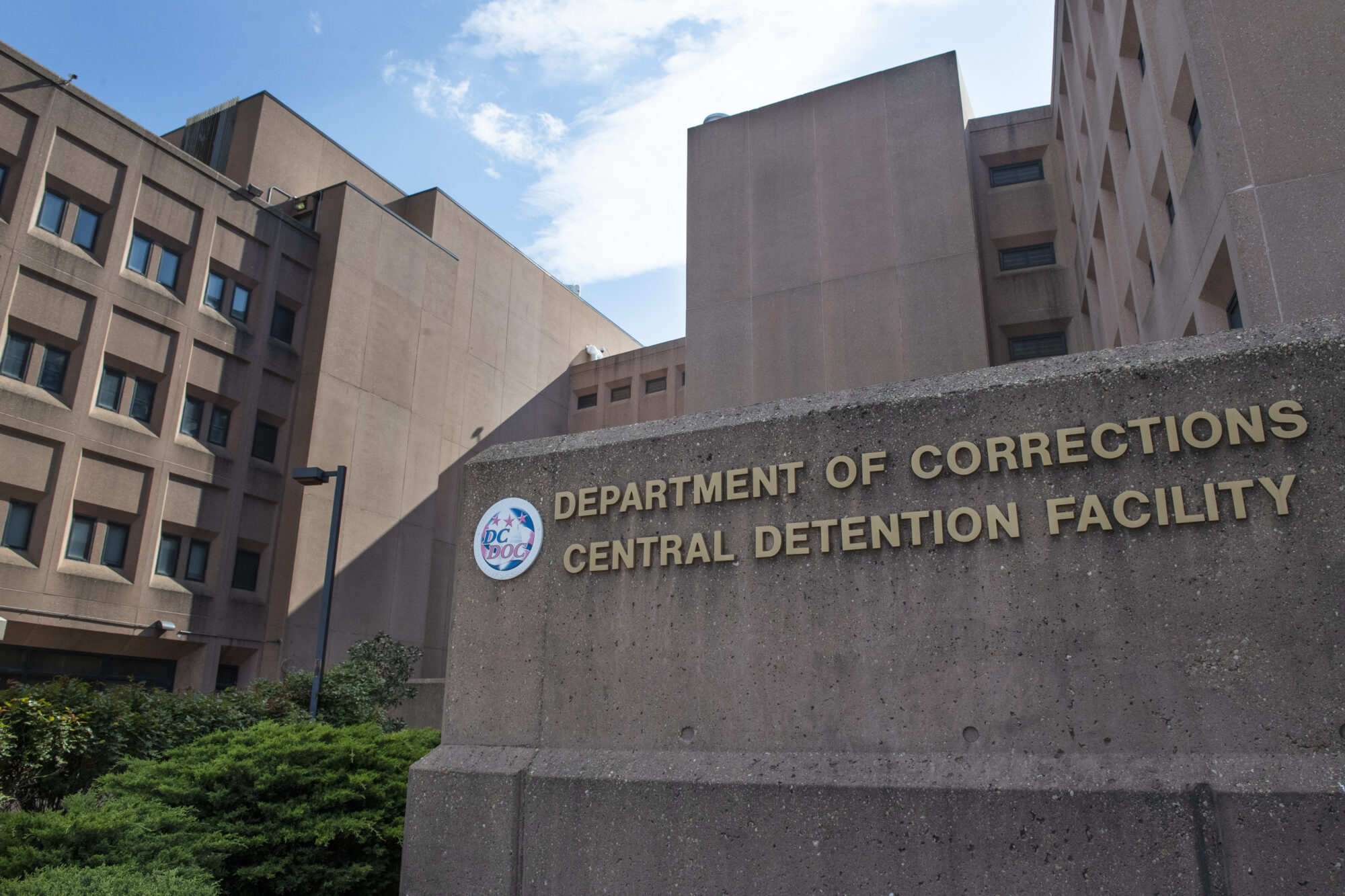

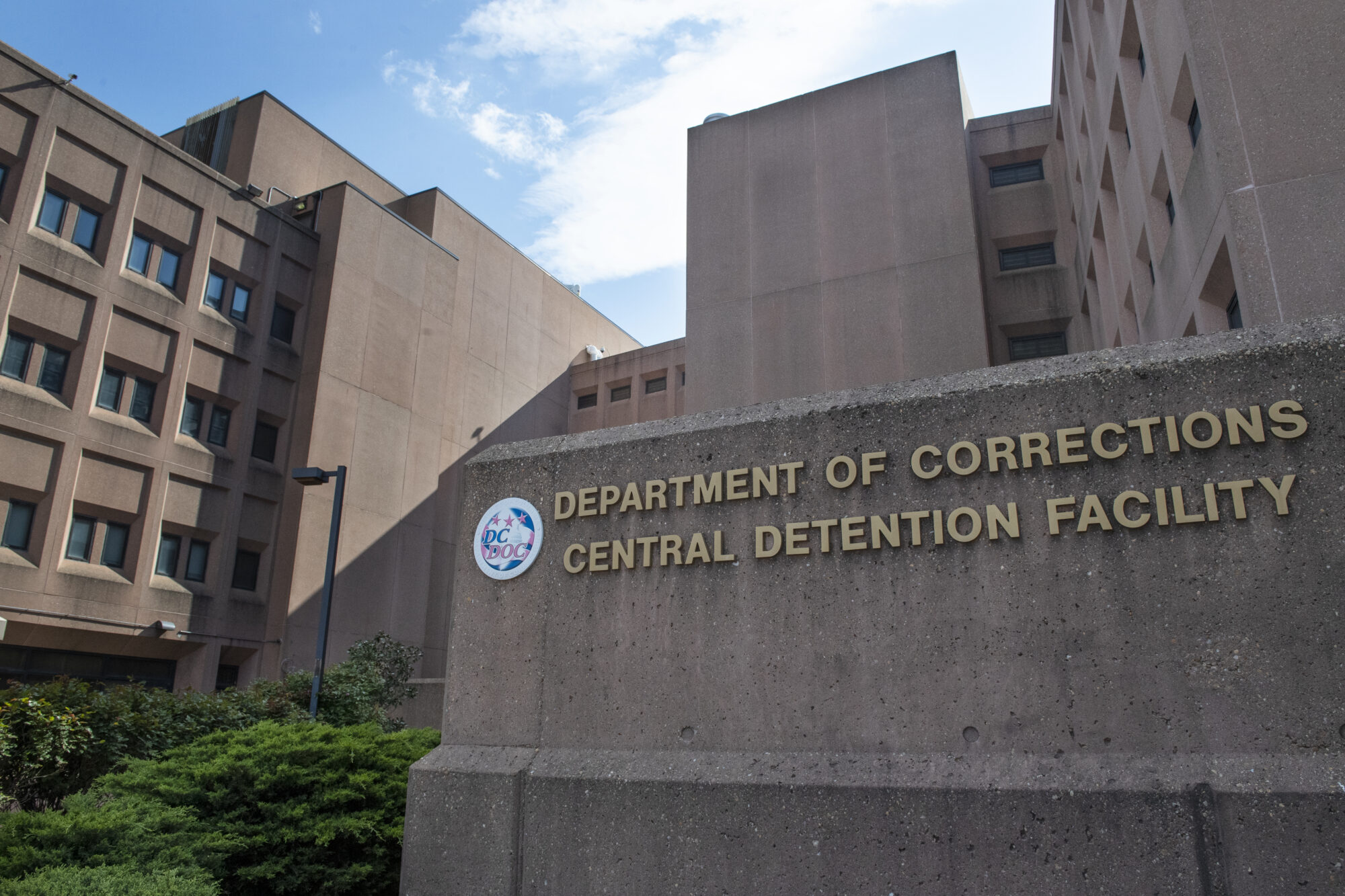

Despite calls to end it over the intervening years, solitary confinement has remained a regular practice in the D.C. Jail, which holds between 900 and 1,300 residents at any given time. Most are pretrial defendants or people serving short sentences for misdemeanor convictions.

In fact, D.C.’s Department of Corrections has been shown to use solitary confinement more than many other correctional systems around the country. An agency memo reported that eight percent of its population were held in solitary confinement in 2018, and nine percent in 2017—three times the national average, according to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report released in 2015. And at the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the agency reportedly held 1,500 people in prolonged isolation for nearly 400 days.

Solitary confinement—defined as prolonged isolation with little to no human contact—has been decried by governments and activists the world over for exacerbating the harmful behaviors that often land people in solitary in the first place. In 2015, the United Nations classified solitary confinement beyond 15 consecutive days as torture for the damage it does to inmates’ physical and mental health. Studies have shown that some residents held in solitary confinement become “actively psychotic and/or acutely suicidal.”

“It creates a situation where if somebody is already suffering from a mental illness, it exacerbates those conditions,” Jessica Sandoval, national director of the Unlock the Box, told Bolts.

“All of the research out there and all of the personal experience we hear people share shows that putting someone in solitary is likely to make them more violent, not less,” said Emily Cassometus, former director of government and external affairs at DC Justice Lab, part of the Unlock the Box D.C. coalition. “Towards themselves, towards other people in the facility, staff and residents included, and more likely to be victims of violence, to be victims of self-harm, and to commit violence once they’re released.”

The D.C. Jail has leaned on isolation as a strategy to deal with inmates experiencing mental health crises in particular, yet publicly contends that it doesn’t put people in “solitary confinement.” In 2022, then-DOC spokesperson Keena Blackmon told a local outlet that the D.C. Jail “does not operate solitary confinement within its facilities,” and only uses “restrictive housing” for suicide prevention.

These are known as “safe cells,” designed to keep suicidal inmates from environments that could endanger their safety. But advocates have argued that these restrictive housing units are just isolation by another name, and say these units more closely resemble punishment than medical care.

“Jail authorities are very clever and they give different names to solitary confinement, but it’s still solitary confinement,” Cheh told Bolts. “They could call it whatever they want.”

A lawyer representing people formerly incarcerated in the D.C. Jail told Bolts of numerous complaints emanating from the restrictive housing cells over the past decade. People incarcerated in these units have complained of being held for 23 hours of each day isolated inside their cell; that they had no access to showers or running water; that they slept on plastic blocks due to a lack of mattresses; that bright fluorescent lighting blazing all day inside their cell made them lose track of time; that they were stripped of all their clothes and personal belongings, including religious material, and even thrown in cells with feces on the walls—likely from past residents who’d covered themselves in it trying to force officers to let them shower.

Between November 2012 and August 2013, four residents of the facility committed suicide, which jail officials at the time said was three times the national average. So the department commissioned suicide prevention expert Lindsay Hayes to survey the area in order to prevent further self-inflicted harm.

In his report published September 2013, Hayes found the conditions “overly restrictive” and “seemingly punitive,” and suggested that the agency avoid isolating at-risk residents to prevent further self-harm.

“Confining a suicidal inmate to their cell for 24 hours a day only enhances isolation and is anti-therapeutic,” he wrote.

While the jail has updated their practices based on Hayes’ suggestions, residents are still reportedly held for up to 22 hours a day in severe conditions. And the suicides haven’t stopped.

Nadeau’s bill makes note of the “deplorable conditions at the District’s jails and restrictive housing units—including flooding, lack of grievance procedures, lack of mattresses, and more.”

The bill seeks to prohibit “segregated confinement” outright within the D.C. Jail. But it still makes an exception for safe cells; it would “strictly limit” their use for suicide prevention, allowing for people on suicide watch to be put in “safe cells” only if “immediately necessary”, and sets a 48-hour maximum limit for holding a person there continuously. It also puts in place other guardrails, such as frequent checks by a medical professional.

This stripped back version, which didn’t include juvenile detention facilities the way Cheh’s bill did, was introduced in an attempt to ease its way to passage.

But even if the bill is passed, the reforms would need to be regularly enforced by an independent oversight body or risk becoming toothless. The D.C. Corrections Information Council was created for such oversight, but in recent years it has received sharp criticism for its inattention to conditions in the D.C. Jail.

“Sixteen years on the Council taught me a few things,” Cheh told Bolts, “and one of them is that you can pass all the laws you want, but if people aren’t enforcing them, then they’re not worth the paper they’re written on.”

The legislation hasn’t progressed much in the new year. In fact, the city council seems to have moved in the opposite direction on criminal justice, passing an omnibus anti-crime bill in early February that would among other things create harsher penalties for gun crimes and theft, with a focus on retail theft in particular. The ERASE Solitary Confinement Act was referred to the judiciary and public safety committee back in November, but there hasn’t been any movement on the legislation since.

Cassometus says she fears that to many D.C. leaders, the invisible nature of solitary confinement is a feature, not a bug. “It’s really hard to draw attention to an issue that no one can see, hear or smell,” she told Bolts. “Solitary confinement has been talked about as a solution to problems but it’s not. It’s locking our problems in a smaller box inside the jail and wishing that they would go away without actually proposing any solutions.”

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.