In Pittsburgh Region, Criminal Justice Reformers Face Off Against Old Guard

The upcoming elections for Allegheny County executive and DA could add to the progressive gains in local politics while GOP candidates are hoping to thwart reforms.

Alex Burness | October 24, 2023

Voters in the Pittsburgh region signaled earlier this year that they wanted a new direction on criminal justice policy, rejecting the punitive practices that have long stood in Allegheny County. In the lead-up to the November general elections, the old guard is making one more stand for its approach.

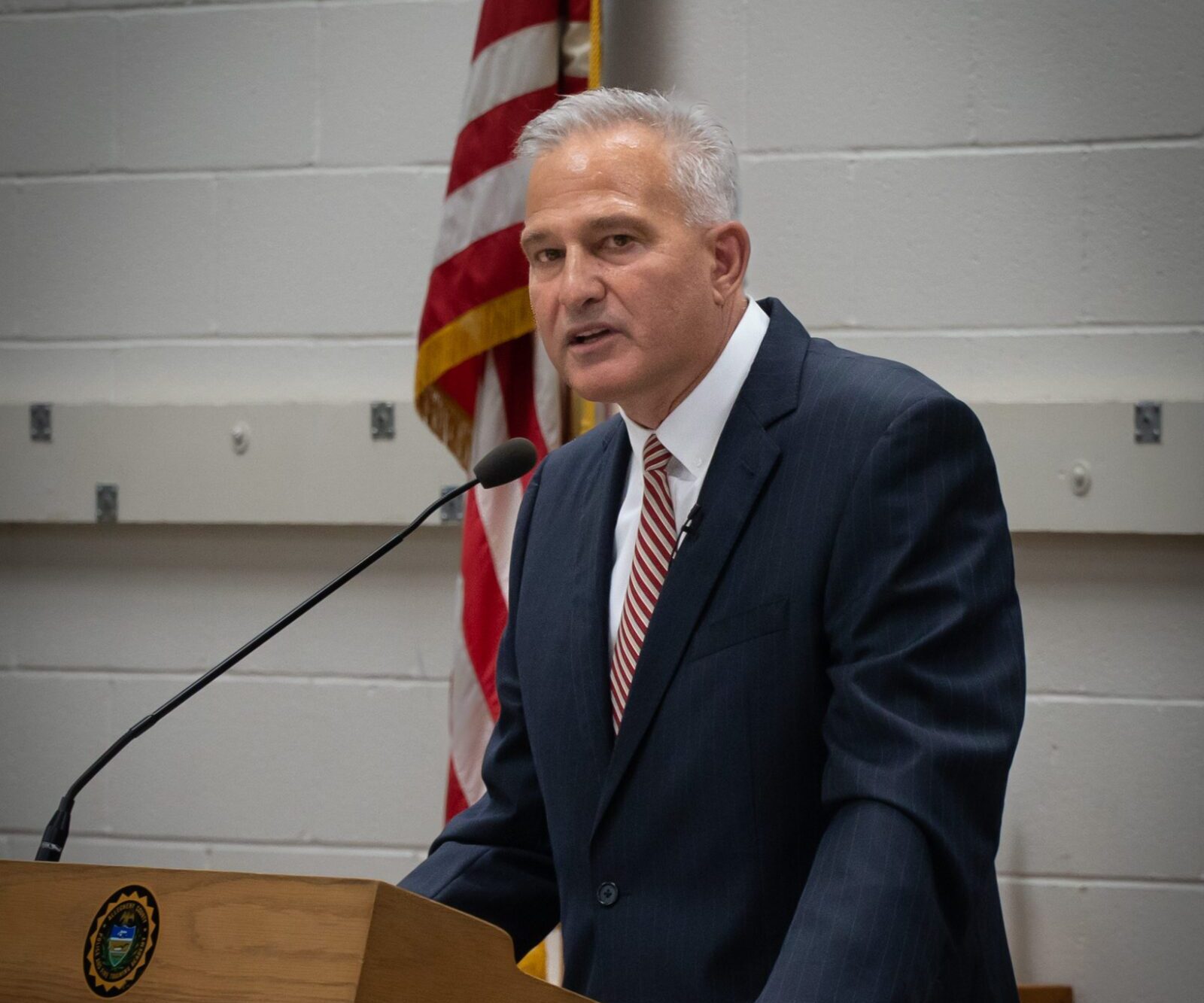

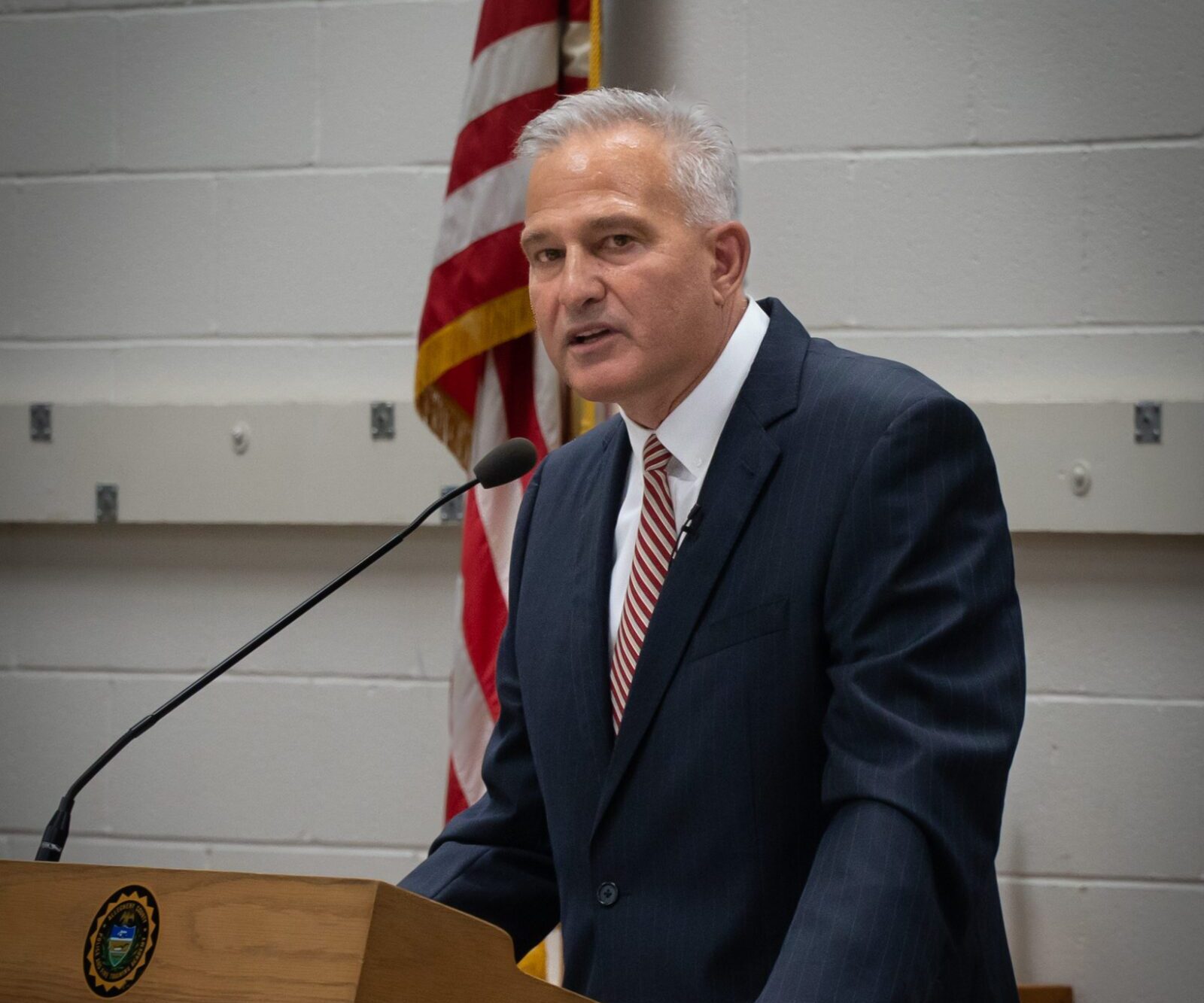

After coasting to reelection for decades with barely any opposition, District Attorney Stephen Zappala lost the May Democratic primary against Matt Dugan, the county’s chief public defender. But Zappala is now running as a Republican in a rematch against Dugan.

Meanwhile, the county government agreed to a controversial contract this fall to reopen a youth detention center, even though the center’s fate had been a major issue in the open race for county executive. Local critics fault Rich Fitzgerald, the term-limited outgoing executive and a moderate Democrat, for tying his successor’s hands through the contract, which will span the next county executive’s entire term. Sara Innamorato, a progressive state representative, won the Democratic nomination to replace him in May, beating two centrist opponents who unequivocally favored reopening the center.

Innamorato now faces Republican Joe Rockey, who, like Zappala in the DA race, is looking to stall criminal justice reforms. While Democrats typically dominate local politics and Joe Biden won Allegheny County by 20 percentage points in 2020, the GOP is hoping law-and-order messaging can deliver its candidates long awaited wins this fall. Recent polls released by the campaigns found tight margins in both races.

But champions of criminal justice reform have already made major strides in the region. Bethany Hallam, a progressive Democrat on the Allegheny County Council, points to other left-leaning candidates who have won recent elections in the area, including Ed Gainey, who became Pittsburgh’s first Black mayor in 2022, and Summer Lee, who won a congressional seat that covers the broader region in 2022 while calling for cuts to jail and prison spending.

Gainey and Lee are now supporting Dugan and Innamorato, as are other prominent Democrats like U.S. Senator John Fetterman. Dugan and Innamorato have frequently appeared together at events this year. “We are very aware of the moment that we’re in right now,” Hallam told Bolts.

She added, “If progressives can win these two, we can show what we can do when we are finally in a position to implement our policies.”

This county of more than one million is very segregated along racial lines, and Black residents are vastly more likely than white residents to be arrested and sentenced to prison. Many areas see virtually no incarceration while some neighborhoods, typically within Pittsburgh, have astronomically high imprisonment rates.

In the run-up to the May primary, progressives worked on winning over the county’s suburban areas, which have less experience of incarceration and which have buoyed Zappala in the past. The last time he ran for re-election, in 2019, the DA received under 10 percent in some of the precincts that most acutely feel the weight of the local criminal system but nearly swept precincts along the outer ring of the county.

This year, Dugan and Innamorato triumphed within the city of Pittsburgh, but they also performed strongly enough in the rest of the county to secure the Democratic nominations.

Rob Perkins, president of the progressive Allegheny Lawyers Initiative for Justice, told Bolts on the night of this year’s primary election that the Dugan and Innamorato wins tell him “that more people from a broader swath of communities are starting to grasp that the criminal justice system is unfair, full of waste, and too often inhumane.”

Hallam hopes that wins in November by Dugan and Innamorato will align the county government with Pittsburgh’s more progressive municipal leadership. The county council on which Hallam sits has of late displayed real appetite for more progressive policy-making, only to run into Fitzgerald’s veto pen; he sought to block council votes to raise the minimum wage and to ban fracking in most county parks. The city’s leadership is decidedly more progressive; Gainey has supported minimum wage hikes and fracking bans, for instance.

Hallam believes that this tension has resulted in missed opportunities to fund programs meant to target root causes of crime. “We have a $1 billion Department of Human Services budget in the county, and we have a city that could really use some of those services to be provided, but it’s been such a head-butting, antagonistic relationship between the county and city,” she said. “It’s going to be transformative to finally have a collaboration.”

Zappala, who flipped parties after the primary, is betting on a reverse dynamic, fueling suburban antagonism toward the urban core to overcome the county’s partisan lean and secure a seventh term in November.

A recent television ad by Zappala paints an apocalyptic picture of what Pittsburgh would look like under Dugan’s leadership, using dark surveillance footage from other cities—gunmen at a gas station in Philadelphia and a carjacking in San Francisco.

Rockey, the Republican candidate in the county executive race, is using a similar strategy. “This is our home, not a laboratory for progressive experiments,” Rockey says in a recent TV spot in which he touted that he is endorsed by local police and jail-staff unions.

But local advocates of criminal justice reform say Zappala and Rockey are shifting the blame. They attribute Allegheny County’s struggles with public safety to the “tough-on-crime” approach the county has pursued for decades, in large part under Zappala’s leadership.

Richard Garland, a formerly incarcerated man who runs a program in Pittsburgh for people newly released from prison, says the county needs to invest more in the wellbeing of young people, particularly in the city’s predominantly Black neighborhoods. And he assailed the local jail for failing to prepare people for what happens after they’re released.

“I’m so frustrated,” he told Bolts. “When I go into the penitentiary it’s full of babies. Babies who don’t have any programs to go to, who are bored. And we expect these things to change? Do we expect society to change overnight?”

Zappala has in the past rejected arguments like Garland’s that strengthening public spending beyond law enforcement is relevant to improving public safety, while Dugan has said that tackling a wider range of economic issues could help disrupt gun violence.

Over his six terms in office, Zappala has aggressively prosecuted low-level drug possession cases, and his critics point to the wide racial disparities in the cases prosecuted by his office. Zappala has said these disparities reflect who commits crimes in the community, not any policy choices he’s made. Dugan has promised to take the county in a different direction, including by seeking to reduce incarceration over low-level offenses and decrease the county’s use of cash bail and lengthy probation terms.

He also pledged that he would set up a position in his office to review the cases prosecuted by Zappala for possible overcharging and innocence claims. The Allegheny County DA’s office currently does not have a conviction integrity unit.

In their debate earlier this month, Zappala mocked a similar initiative set up by DA Larry Krasner in Philadelphia. Krasner’s unit has uncovered dozens of wrongful convictions since 2018. “How’s the conviction integrity unit working out for Philadelphia?” asked Zappala during the debate. “The conviction integrity unit in Philadelphia has exonerated over 30 people,” Dugan responded.

After losing in the primary, Zappala’s ideas have found a cozy home in GOP politics. No Republican filed to run for DA, and party leaders organized a write-in effort to hand him the GOP nomination—a maneuver that comes with a relatively low threshold; Zappala accepted it after losing the Democratic primary. The DA has since aligned himself with GOP campaign firms—including one that worked with former U.S. Senator Rick Santorum. The chairman of the Allegheny County GOP told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, of Zappala, “I think we have similar views on law and order.”

When they debated, Dugan accused Zappala of airing “right-wing GOP attack ads,” saying the incumbent’s tactics are a sign of desperation. Zappala attacked Dugan for receiving outside funding from George Soros, the billionaire who has supported reform candidates around the country. Zappala has the endorsement of Andrew Yang’s Forward Party, which has also endorsed Rockey in the county executive race.

Similarly to Dugan, Innamorato has pledged to tap into county coffers to better fund services that may reduce crime, such as behavioral health care and free recreational programs for kids. Ahead of her competitive primary this spring, she said this goal would be her north star when it comes to settling the heated local debates over youth detention. The local youth jail, the Shuman Juvenile Detention Center, shuttered in scandal two years ago, and local politicians and organizers have fought over whether—and how—to reopen it.

Innamorato did not take a definitive position in the runup to the primary on whether she would reopen Shuman, but her victory over candidates who were unambiguously in its favor created question marks over the future of the lock-up.

But this fall, Fitzgerald and local courts entered into a five-year contract with a private operator to reopen and run the Shuman Center.

Innamorato and Rockey, the candidates running to replace him, have both criticized the contract. They have each disagreed with privatizing the detention center; and they’ve both said that the length of the contract will limit the options of the next executive. But they’ve both also said that they favor at least temporarily reopening Shuman; at minimum, they say, it’s a way to get kids out of the county’s adult jail, where they’ve often been warehoused since Shuman’s closing.

Innamorato and Rockey did not provide comment for this article. Fitzgerald declined to comment through a spokesperson on the contract. He also declined to endorse a successor.

The county council is now suing Fitzgerald over his decision, asserting that he overstepped his authority by making such an impactful move without the consent of the council.

Reporting by local public radio station WESA confirms that Fitzgerald’s move will tie the hands of the next executive. The contract allows the county few options for termination, and it provides for little oversight beyond that conducted by the county controller, who is currently reviewing the contract and who has power to audit the facility.

Allegheny County’s controller, Corey O’Connor, assumed that position in 2022 when then-Governor Tom Wolf appointed him to fill a vacancy, and is now running for a full term this fall against Republican Bob Howard. O’Connor has used his first years in office to highlight the failings of the local criminal legal system, including by releasing an audit that underscored how thoroughly the county jail upends the lives of entire families. The audit blamed Allegheny County for doing very little in the way of outreach to the children of the adults it incarcerates, further destabilizing households. O’Connor’s office found nearly 12,000 children largely abandoned by the county in this way between January of 2021 and September of 2022.

O’Connor, who has endorsed Dugan and Innamorato, told Bolts that he thinks the elections this year will further illustrate the county’s growing comfort with criminal justice reforms.

“Places that were predominantly Republican in the suburbs are starting to turn blue, and they’re turning blue not just in countywide races but council races, school board races,” he said. “It’s all about people organizing and getting people out to vote.”

Stay up-to-date

Pennsylvania Votes

Bolts is closely covering the ramifications of Pennsylvania’s 2023 elections for voting rights and criminal justice.