In Pennsylvania’s 2023 DA Races, There’s Already a Winner: Unopposed Prosecutors

The debates are over before they begin in much of the state, though a few counties like Allegheny still stand out for offering voters a stark contrast on criminal justice policy.

Daniel Nichanian | March 22, 2023

This is the first installment of Bolts’ primers on 2023 prosecutor elections. Explore our guides to DA races in New York and across the South in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Virginia.

Tom Marino, a former member of Congress, is running this spring for a job he held more than two decades ago: district attorney of Lycoming County, in Central Pennsylvania. On his website, he vows to “prosecute offenders to the fullest extent of the law,” and in the brief list of issues he says he’d tackle with a “tough-on-crime approach,” he includes the fact that “drugs are making their way into our neighborhoods.”

Lycoming County has been hit hard by the opioid crisis, overwhelming local officials with a surge in overdoses. But Marino’s campaign posture today sticks out given the accusations he faced just five years ago that he worsened this trend.

In late 2017, Marino’s nomination to be then-President Donald Trump’s drug czar derailed after The Washington Post and 60 Minutes reported that he pushed legislation that made opioids more readily available. The investigation revealed that Marino collaborated with the pharmaceutical industry to draft language that gutted the Drug Enforcement Administration’s authority to go after large drug companies suspected of fueling the crisis, all while receiving big donations. Besides sinking Marino’s appointment, the news sparked a national reckoning over his law and, back home in Lycoming, condemnation as well as fresh reporting on overdoses.

But any debate over Marino’s record and how it fits with his new campaign’s rhetoric ended before it even began: No one filed to run against him.

Pennsylvania’s deadline to run for DA as a major-party candidate passed on March 7 with no other contender entering the race, leaving Marino highly likely to win the job and complete his comeback with little additional scrutiny. Marino, who also survived a residency challenge last week, did not reply to Bolts’s requests for comment over his legacy and platform on drugs.

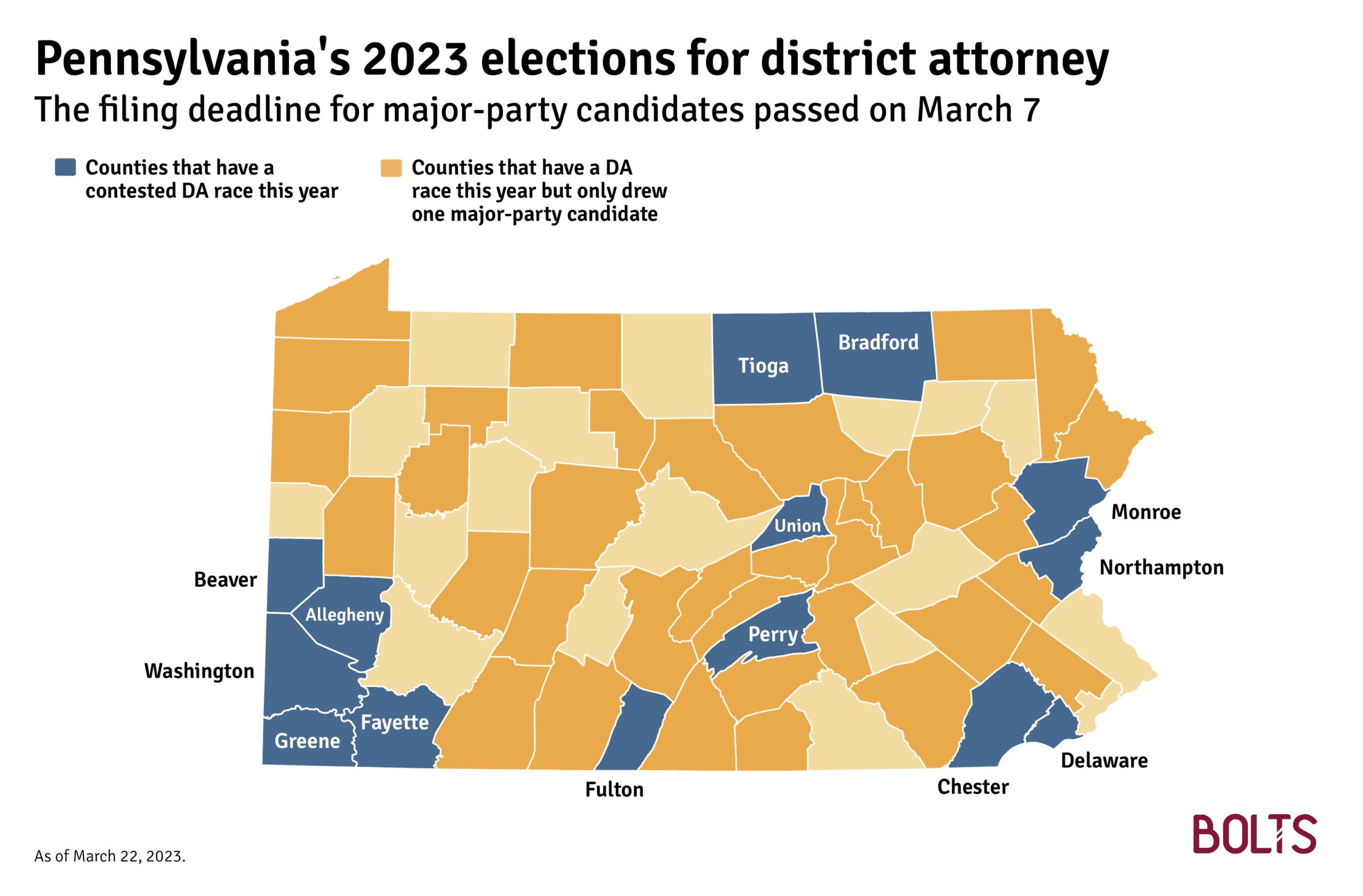

The same scene repeated itself throughout the state this month. Upon compiling the list of candidates in the 49 Pennsylvania counties with DA elections this year, I found that only 14—less than a third of the total—drew multiple candidates, with a few of those races seeming to offer voters a stark choice.

Thirty-five counties, meanwhile, drew only one candidate by the deadline.

Missed windows for democracy

That’s 35 candidates—typically incumbents, but in six cases nonincumbents like Marino—who are poised to waltz into office without facing much scrutiny into their policies. In Dauphin County, where PennLive recently reported on mounting jail deaths and local officials offering little information or accountability, DA Frank Chardo faces no opposition, just like the last time he ran in 2019. The same is true for DA Brian Sinnett in neighboring Adams County, where the DA’s office faced allegations that it is not taking rape complaints seriously. In Lehigh, which saw sustained activism after prosecutors decided to not charge police officers in a publicized use-of-force case, the DA is retiring and his chief deputy is the only candidate who filed to replace him.

The strangest saga is unfolding in Northumberland, where DA Tony Matulewicz filed his petition too late by a matter of minutes and was denied a ballot spot. He is suing to be reinstated but, for now, challenger Mike O’Donnell remains the sole qualified candidate. O’Donnell, who is a Republican like Matulewicz, works as a defense attorney and said upon entering the race that “he wanted to fix a broken system,” but did not reply to questions about what that means.

Independents may still file to run later, but it’s very rare for candidates outside of the two major parties to win. In 2019, when each of these 49 counties held their last DA race, all 49 winners had filed as a Democrat or Republican. Newcomers could also mount uphill write-in campaigns.

It’s common across the country for DAs to run unopposed. For one, it’s hard for attorneys to challenge a sitting prosecutor without fearing professional repercussions should they lose, especially in smaller communities. Still, the number of Pennsylvania counties hosting contested elections plummeted this year compared to 2019. At the time, 24 of the 49 counties drew multiple major-party candidates, compared to 14 counties this year.

The pattern is also not confined to the state’s smallest jurisdictions. There are 12 DA elections in counties with at least 250,000 residents, and only four drew multiple contenders; in Montgomery County, for instance, a county of more than 800,000 residents, incumbent DA Kevin Steele will be running for re-election unopposed for the second straight cycle.

“Many people just don’t know all of the power that district attorneys actually possess,” says Danitra Sherman, the deputy advocacy and policy director at the ACLU of Pennsylvania. “As voters, we often get excited about presidential elections, but not so much about local races, or state races at times, when those that hold positions at these levels have more say on and decision making power over the day-to-day life.” The state ACLU launched a voter education drive on the role of DAs in 2017, and in 2019 they sent out questionnaires to candidates, asking for their views on matters ranging from sentencing to bail, but many did not reply. Sherman says they recently sent out questionnaires to some candidates again this year.

In counties with contested DA races, this year is voters’ first opportunity to weigh in directly on criminal justice since the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 and the latest round of GOP attacks over crime, which has put issues surrounding policing and public safety squarely in Pennsylvania’s political spotlight. Yet even when there’s a contested race, candidates often downplay the huge amounts of policy discretion that comes with the role.

My own review of Pennsylvania’s 14 contested DA races found that many of the people who filed this year are running as status-quo candidates (such chief deputy prosecutors bidding to replace their retiring boss), competing largely over who has the most professional experience as a prosecutor, and eschewing sharing their thoughts on issues—all standard fare in DA races.

In addition, some candidates have little to no campaign presence at this stage and did not answer requests for comment. That includes the sole challenger in Delaware County, one of the most populous counties with a contested race.

Primaries in Pennsylvania are on May 16, and general elections are in November. State voters also weigh in on many local and state elections this year, including a seat on the state supreme court, county sheriffs, and Philadelphia’s mayor.

Still, a few DA elections are presenting voters with some contrasting paths on criminal justice policy.

What to still watch for

The year’s marquee race is the DA election in Allegheny County, home to Pittsburgh, where longtime incumbent Stephen Zappala faces the county’s chief public defender, Matt Dugan.

Over his nearly 25 years in the DA’s office, Zappala has embraced a reputation for harsh prosecutions—other than in cases of police shootings—and sternly opposed advocates who have pushed for decarceration, accusing them of disregarding victims. “I don’t agree with their philosophy on a lot of things,” he said during his most recent campaign, explaining why he was “done with socialists and ACLU forums” and skipping some candidate events. Investigations have revealed significant racial disparities in prosecutions under Zappala’s watch but he has routinely dismissed addressing systemic inequalities as beyond the purview of his job. “I’m not running for public defender,” he quipped four years ago.

Now a public defender is running against him, adding to a wave of outsiders, including civil rights attorneys, who have run for DA nationwide in recent years. Dugan is pressing a basic disagreement over whether the DA’s office should even be tackling the root causes of crime and tracking class and racial disparities. “I do see a place for the district attorney to think more about crime prevention and to address the issues that are really driving people into the criminal justice system in the first place,” he told the Pittsburgh City Paper.

Hundreds of miles away, in Monroe County, the retirement of a local DA—Republican David Christine—has sparked an intriguing three-way race. In the Republican corner is Alex Marek, an assistant DA in a neighboring county who is pledging to bring a “tough on crime” approach.

Democratic candidate Donald Leeth takes exception to that moniker. “Unfortunately being tough on crime is always locking up more people for a longer period of time, and I think the evidence has shown that that doesn’t work, that doesn’t make us a safer community, that doesn’t address the underlying issues within our society and our criminal justice system,” he told me.

Leeth used to work as an assistant DA but says he became more aware of disparities in prosecution as a defense attorney. He faulted racial disparities in the county’s court system and an overreliance on police officers as “first responders for everything.” But he also remained largely cautious when it came to specifying reform he’d implement, for instance saying he’d want to recommend cash bail in fewer cases, but also that it has its role in the court system.

Leeth also said he “would not be open” to seeking death sentences if he was elected DA, and called on the death penalty to be repealed.

Also in the running is Democrat Mike Mancuso, who currently works as the county’s chief deputy prosecutor, and who did not reply to a request for comment on the death penalty and other issues. (The winner of the Democratic primary between Leeth and Mancuso will face Marek in November.)

Monroe is one of the ten counties in Pennsylvania that has sentenced someone to death over the last decade, according to data gathered by the Death Penalty Information Center. Pennsylvania’s Democratic governors have imposed a moratorium on executions but the death penalty remains available and state prosecutors regularly seek it.

Washington County is also on that list. Republican DA Jason Walsh came into office in late 2021 after his predecessor’s death and he has since pursued death sentences aggressively; the county had eight capital cases as of August, and more since. Walsh now faces Democrat Christina Demarco-Breeden, an assistant DA in a neighboring county. When I asked Demarco-Breeden if there are aspects of the DA’s office that she wishes to change, she zeroed in on Walsh’s use of the death penalty. She is concerned that it just keeps growing and that the county’s defense resources are at a breaking point. But she also said that, if she became DA, she herself would remain open to applying the death penalty “to the most brutal homicides.”

Some Democratic lawmakers are championing legislation this session to abolish the death penalty. “My job is to make sure that’s not even an option,” said State Representative Chris Rabb when I asked how he hopes DAs handle capital cases in the meantime. The money “could be much better spent on any number of things, most notably violence prevention so that we don’t have as many people committing the murders that get people on death row to begin with.”

Rabb, who represents Philadelphia, was a vocal defender of Philadelphia DA Larry Krasner, a figurehead for so-called progressive prosecutors, against state Republican efforts to remove the DA from office last year; Krasner, who easily won re-election in 2021, is not up again until 2025.

Rabb says the GOP attacks on Krasner and other tough-on-crime messaging backfired—Democrats won a high-profile U.S. Senate race and flipped the state House—because most Pennsylvanians believe in reforming the criminal legal system. “They believe in second chances, and having parole and probation reform so that people are not surveilled for decades,” Rabb told me.

“Spending so much time denigrating Larry Krasner did nothing else than energize Philadelphia in saying, ‘You folks who don’t live in Philly claim to care about us, but what are you doing for us other than demeaning someone who we voted for twice?’” Rabb added. Krasner, unlike most of his peers, has faced opponents in every primary and general election.

Democrats’ takeover of the state House in the midterms changed the political dynamics around criminal justice reform by ushering progressive leaders into power. But Liz Randol, legislative director of the state ACLU, says one thing that hasn’t changed in Harrisburg is the role of the Pennsylvania DA Association, the influential group that lobbies on behalf of state DAs and has helped shape state laws to be more punitive. Randol is watching whether 2023 chips away at state prosecutors’ typical role as chief antagonists to reform legislation.

“The prosecutorial mindset runs through the entire criminal legal system, from legislating to charging, to sentencing,” said Randol. “Because the system is largely driven by the prosecutorial side of the equation, it’s going to take a lot to change it. But I certainly think you can poke holes in that veneer.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Pennsylvania Votes

Bolts is closely covering the ramifications of Pennsylvania‘s 2023 elections for voting rights and criminal justice.

Explore our coverage of the elections in the run-up to the May 16 primaries.