Slouching Toward the Big Lie in Ohio

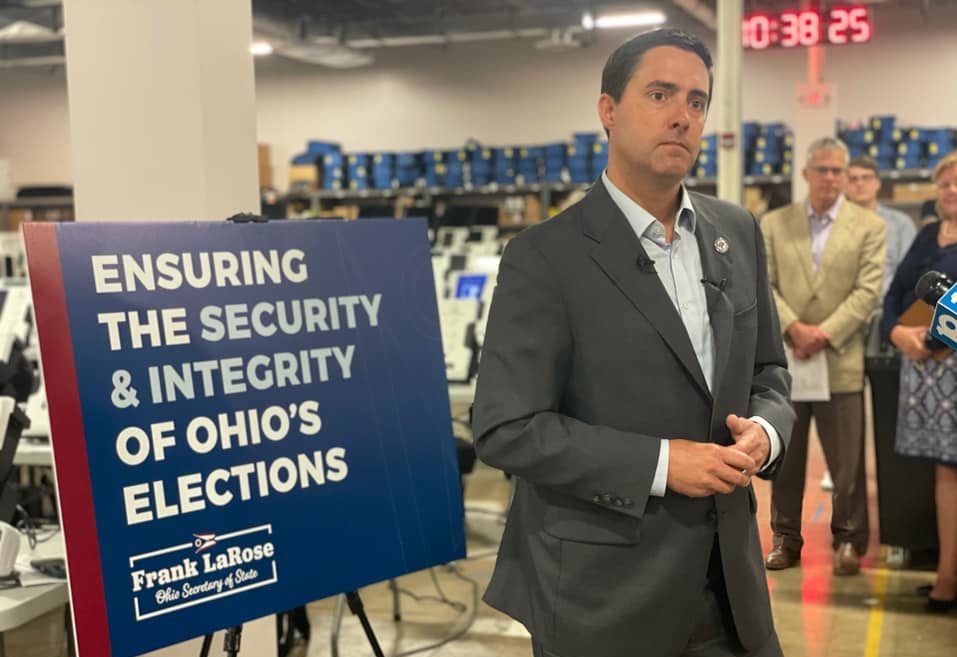

Republican Secretary of State Frank LaRose faces a far-right challenger, but he too has voting rights advocates worried as he echoes Trump’s baseless claims of election fraud.

Jeremy Borden | March 10, 2022

In late 2019, voting rights advocates began to celebrate a federal district court win that they believed would help them get ballots to Ohioans who often don’t get to vote. The ruling would have helped voters who are eligible but stuck in jail during an election and typically denied ballots—for instance, people detained pretrial because they can’t afford bail.

But that victory proved short-lived. Ohio’s Republican Secretary of State Frank LaRose, the named defendant in the lawsuit, appealed to overturn the ruling. A federal appeals court agreed in 2020, saying that voters in jail are “no more burdened than any other elector” facing unforeseen complications—similar, the court said, to someone who leaves town unexpectedly to attend a funeral.

Danielle Lang, an attorney with Campaign Legal Center who helped bring the lawsuit, says she was dismayed by LaRose’s decision to appeal. “These are folks that we know are eligible voters that the state is physically restraining from going to the polling place and voting, and they’re also not providing any alternative,” she told Bolts. “I find that appalling.”

Today, LaRose is running for a second term as secretary of state, but his profile in this campaign has been markedly different. Facing a far-right challenger who peddles conspiracy theories about the 2020 presidential election, LaRose is getting cast as a bulwark of democracy.

John Adams, a former state lawmaker running against LaRose in the Republican primary scheduled for May, avidly repeats the false claim that the 2020 election was stolen from President Donald Trump. “Everybody knows after the last election last year that we got robbed,” Adams says in a video on his campaign website. “We got robbed and the Republican Party did little if anything to fight back… That’s why I’ve decided to run.” Adams has also taken to calling LaRose a “never Trumper.”

LaRose pushed back against efforts by Trump’s closest allies to discredit voting machines and decertify election results after the 2020 presidential election, as reported by The Washington Post. So far the script writes itself: Trump’s forces are coming for yet another Republican who dared stand up to the former president.

But LaRose has himself repeatedly clashed with voting rights groups. In 2020, he imitated other Republicans like Texas Governor Greg Abbott in limiting the availability of dropboxes across Ohio, making mail-in voting tougher during the pandemic.

Since then, LaRose has gone further in embracing the premises of the Big Lie. “President Trump is right to say voter fraud is a serious problem,” he wrote last month in a Twitter thread that also attacked the “mainstream media” for “trying to minimize voter fraud.” LaRose’s office declined to comment for this story.

As the politics of the Big Lie continue to capture a large swath of the GOP and threaten the health of American democracy, the record of establishment Republicans like LaRose may get overlooked by comparison. But voting rights advocates caution that state officials were already weakening democracy in Ohio before Trump and his followers’ efforts exacerbated that trend. And they have continued to further anti-voter policies on their own.

On Tuesday, Governor Mike DeWine, a longtime fixture in Ohio’s GOP politics, appointed a former lawmaker who has amplified false claims about a stolen election to the state’s elections board. And given LaRose’s past policies and his slide into Trumpish rhetoric on voter fraud, barriers to expanding ballot access will persist regardless of who wins the May 3 secretary of state primary. Ohioans in jail who are eligible to vote will still have difficulty voting.

Ohio’s secretary of state is a powerful office. It oversees broad election administration decisions across the state’s 88 counties, responds to lawsuits, and serves as a tiebreaker in the rare case when bipartisan county election boards deadlock. LaRose also sits on Ohio’s redistricting commission, which this year has failed to advance new maps after the Ohio Supreme Court struck down previous Republican gerrymanders as unconstitutional.

LaRose is now favored to win re-election and keep those powers for the next four years. He had about $1.8 million campaign cash on hand as of January, according to his most recent campaign finance report, and he secured the endorsement of the Ohio Republican Party. Adams, on the other hand, had about $41,000 to spend. In an age of anti-incumbent fervor, no primary candidate should be counted out, especially if Adams draws more support from conservative groups, but he has yet to catch fire or land Trump’s endorsement.

The sole Democratic candidate, Chelsea Clark, is a Forest Park city councilmember who is running on strengthening access to the ballot with measures like automatic voter registration. Democrats last won the secretary of state’s office in 2006, and the party faces a tough cycle across the country in a historically difficult mid-term year. In the 2018 general election, LaRose prevailed by four percentage points against Democrat Kathleen Clyde, who ran on a similar platform.

When LaRose began his term in 2019, then-Ohio Democratic Party Chair David Pepper hoped to build a constructive relationship with him. So he invited LaRose to a forum to speak with Democrats about election administration issues. But Pepper told Bolts the relationship soon began to sour as LaRose backpedaled on early promises.

“He wants to brand himself as ‘aw shucks I’m good for the voters’ but at every turn he does what the far right of the [Republican] party wants him to do,” said Pepper, who has since left his role as head of the state party. “He is, in many ways, more dangerous than the wide-eyed conspiracy theorists, because he’ll do what they want him to do, but he’ll dress it up like it’s more legitimate.”

Pepper’s distrust of LaRose stems in particular from the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, when LaRose sided with Trump’s crusade against voting by mail. With voters likely to rely on mail-in ballots in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, voting and civil rights groups wanted more dropboxes placed around the state to help them, especially given the fears about the U.S. Postal Service’s ability to handle the influx.

But LaRose limited each county to no more than one dropbox location. A county of more than 1.3 million residents would have as many dropbox sites as one of 13,000 people.

Initially, LaRose said that state law gave him no other option, but that he could order more dropboxes if a court blessed his authority to do so. “We’ll follow what the court says,” LaRose’s attorney told a federal judge, according to a Talking Points Memo story. “If it’s legal to add extra dropboxes, then I’m certainly open to the idea,” LaRose had previously said, according to the Statehouse News Bureau.

So when a state court said that LaRose could not prevent counties from adding more dropboxes, calling restrictions “arbitrary and unreasonable,” voting rights groups celebrated. “We were expecting he would champion [dropboxes] after the court said he had the opportunity to champion it,” Kayla Griffin, the Ohio State Director of All Voting is Local, told Bolts. “Instead, he took a hard-nosed stand to oppose it.”

LaRose appealed the ruling. Even after an appeals court confirmed that he had the authority to expand access to dropboxes, but was not required to, LaRose doubled down. He directed counties to set up dropboxes at the sole location of the county board, and fought in court to shield his decision.

Voting rights advocates say that LaRose’s policy was disproportionately harmful in Ohio’s most populous counties, which have a higher share of Black residents. In the fall of 2020, LaRose blocked a plan by the board of elections of Cuyahoga County (Cleveland) to establish seven dropbox locations—a plan that had even earned the unanimous support of the board’s Republican members, in a county of more than one million people.

Expanding access to the ballot would also benefit voters in the state’s more rural areas. “I was hearing from people who were in predominantly red communities that said it would be so much more beneficial if they could put a dropbox on the outer lines of their counties,” Griffin said.

ProPublica reported that, during the controversy, LaRose’s office was coordinating with Hans von Spakovsky, the Heritage Foundation fellow whose claims about widespread illegal voting have been debunked in court and by experts. Von Spakovsky and other conservatives serve as consultants on election administration policy in many red states.

Catherine Turcer, a longtime voting rights advocate and the executive director of Common Cause Ohio, praises the state’s model for administering elections, which she calls “Noah’s Ark.” Each county’s board of elections has two Republicans and two Democrats, who are nominated by local political parties and are affirmed or rejected by the secretary of state. They work side by side to adjudicate ballots, decide on voter outreach, allocate dollars toward voter machines and other shared decisions. There is also always at least one Democrat and one Republican at polls or tabulating ballots.

Turcer said LaRose earned plaudits when he asked elections officials to get verified on social media so voters could trust what they post.

Allegations of voter fraud are “vanishingly rare,” she said.

But for years now, Ohio Republicans have trumpeted claims of voter fraud like von Spakovsky’s to change election laws and to restrict options for both voters and election administrators.

In 2011, the GOP-led General Assembly passed a strict voter ID law. In 2014, they made it likelier a mail-in or provisional ballot would be rejected over minor errors, like a spelling mistake or a missing digit on a social security number. In 2016, they reduced the early voting period by a week and eliminated the so-called “Golden Week,” when voters could register and vote at the same time. And last year, they adopted a law that prohibits elections officials from partnering with outside groups.

That law is ostensibly meant to block election administrators from accepting outside funding: In 2020, LaRose and strapped local election boards accepted grants from a foundation associated with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg to help run elections and secure equipment, angering conservatives. But there is also widespread concern that the law could ban more than outside donations. Election officials may be reticent to help voters or engage with outside groups with the threat of criminal prosecution looming over them.

Griffin said her organization has worked with county officials in various places in the past to ensure disabled voters have access to the polls or help with education efforts. Those programs are now in doubt. “We’re on high alert,” she said.

When he jumped into the secretary of state race, Adams said that those 2020 grants were one of his main reasons. The far-right group Ohio Value Voters, which has drawn attention for running candidates for school boards in Ohio, also endorsed Adams over LaRose because of them.

Adams is also running on making Ohio’s voter ID rules even more strict. If he wins, he would have the authority to issue key directives to local election administrators in the run-up to the 2024 elections, giving believers of the Big Lie one of their most powerful positions.

But many in Ohio are also nervously monitoring LaRose’s growing embrace of baseless rhetoric about widespread voter fraud. LaRose has “jumped foursquare on the fraud bandwagon,” the editorial board of the Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote in late February, in reference to his tweets siding with Trump, “despite the very low levels of wrongful voting consistently seen in Ohio.”

“He’s starting to repeat the conspiracy theories we’ve heard throughout the country,” Griffin said of LaRose. “It does make us wonder what the end game is.”