Michigan Democrats Sprint Through ‘Pro-Voter’ Agenda to Close Out 2023

Important bills remained on the table, though, and Democrats will have lost their House majority for months when the legislature reconvenes next year.

Camille Squires | November 22, 2023

This is the second part of our series this fall on voting reforms in Michigan, after reporting last week on landmark changes to automatic registration. To stay on top of voting rights information, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

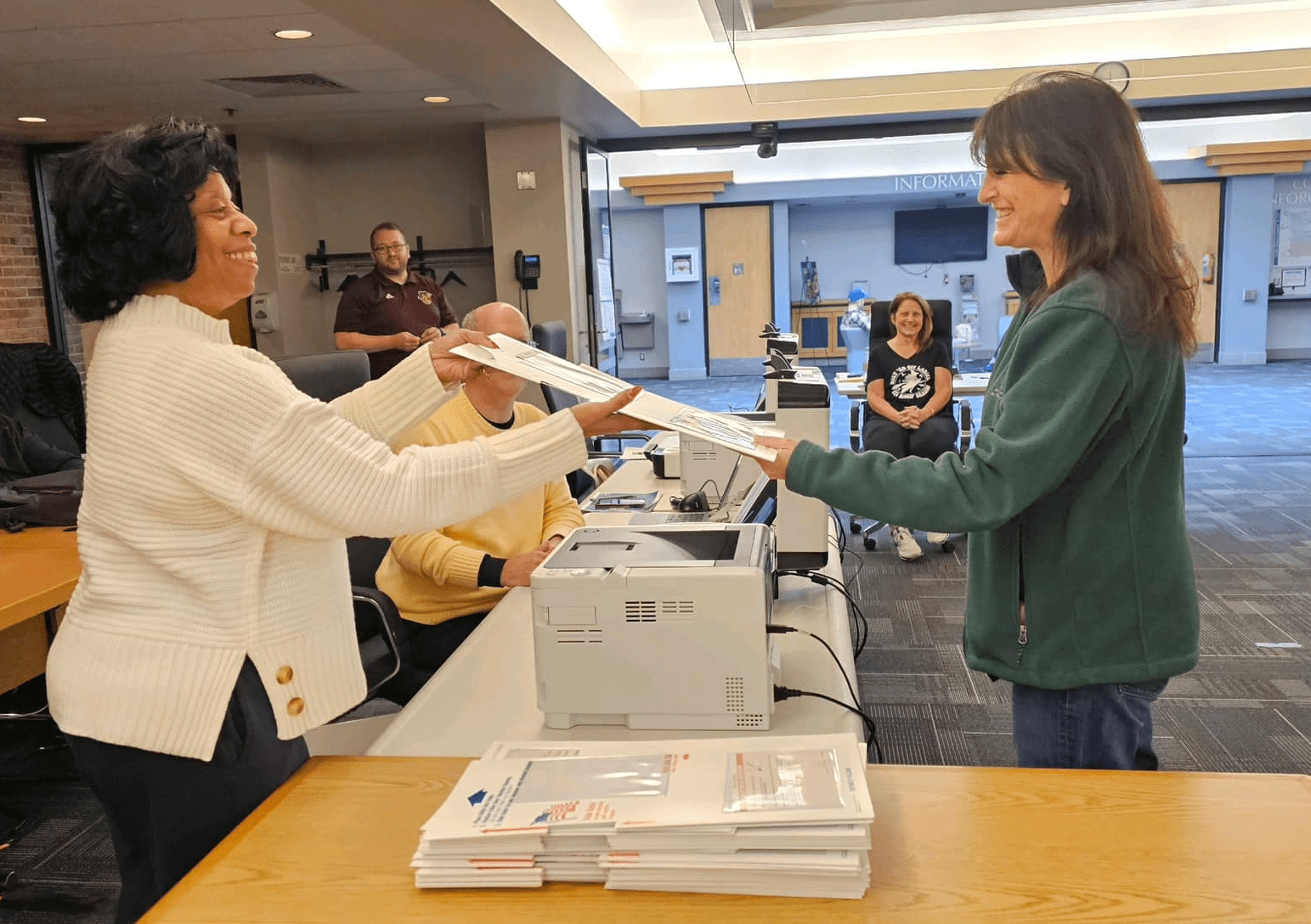

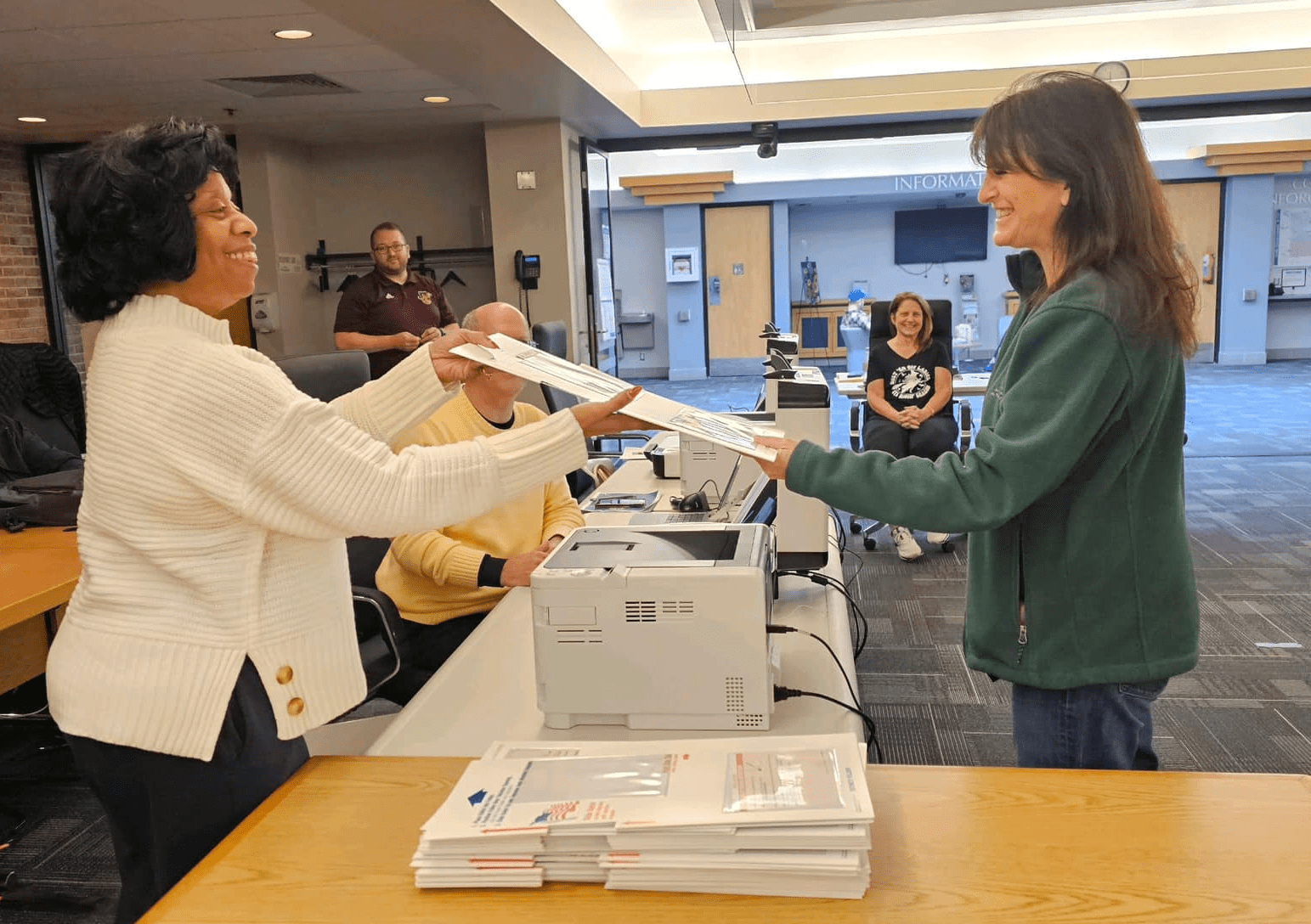

When Oakland County Clerk Lisa Brown looks back on the nine days of early voting she administered in the lead-up to Michigan’s Nov. 7 local elections, she considers it not only a logistical success, but a good time for those working the polls.

The people who came out to cast ballots were especially pleasant, she recalls, and election workers got to run the polls without the pressure of long and crowded Election Days.

The southeast Michigan county was one of ten throughout the state where some voters tried out in-person early voting this fall, a first in this state. The innovation was one of the key provisions of Proposal 2, a constitutional amendment that voters overwhelmingly approved last year that contained many other changes aimed at protecting and expanding ballot access, including mandating ballot drop boxes and funding postage for mail-in ballots.

With the entire state set to adopt in-person early voting in 2024, Brown and some other clerks took advantage of the lower-turnout races this year to try out early voting as a pilot program.

“We’re glad to be that resource for others,” Brown said. “It will make it easier for other clerks next year that we can share our experience, advice and knowledge.”

In addition to adopting Prop 2 last year, Michigan voters delivered the state House and Senate to Democrats, and reelected Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer, giving the party its first trifecta control of the state government in 38 years. This came after several years of Republican legislators—many of them motivated by Trumpian voter fraud conspiracies—pushing for new voting restrictions, while others in the GOP played with overturning elections and ran for office on proposals to unwind the election system.

The newly-empowered Democrats, by contrast, made democracy legislation a priority. Powered by what voting access advocates are calling a “pro-voter” majority in the House and Senate, the legislature has passed a raft of new legislation that’s meant to make it easier for people to register and cast ballots, to shore up election systems, and to protect election workers.

“There was a call to action with the passage of Proposal 2,” said Democratic Representative Penelope Tsernoglou, who was elected to the House as part of this blue wave in 2022. “It was clear that people in Michigan wanted more voter access and wanted to support whatever we could do to…make voting easy, accessible, streamlined.”

But key pieces of this agenda were left unfinished—including a state-level Voting Rights Act and a bill to end prison gerrymandering—and Democrats’ window of action to push them through may be closing just as quickly as it opened. The party finds itself in a very tight spot if they hope to pass more of it by next fall’s elections, when they risk losing control of the legislature.

The Michigan legislature adjourned for the year on Nov. 14, about a month earlier than usual, and when it returns Democrats will have lost their ability to pass legislation through the state House, likely through the middle of 2024. That’s because two Democrats are resigning from the House after winning mayoral races on Nov. 7, leaving the chamber evenly split between Democrats and Republicans until their blue districts hold special elections next year.

This puts pressure on 2024, a year that won’t just be a deadline for Michigan Democrats to complete their voting rights agenda, but also the first proving ground for some of their new elections measures, all against the backdrop of possible renewed efforts by Donald Trump to test the democratic system.

Kim Murphy-Kovalick, programs director of Voters Not Politicians, a group that organized to get Prop 2 on the ballot in 2022 and lobbied Lansing on voting rights this year, is glad to see so much legislation pass but acknowledges that there’s still much work to be done.

“We have a pro-voter legislature but our majorities are very slim, and there are still elected officials who do not support these measures,” she told Bolts. “So while Michigan has made great gains in the last few years, we’re in a tenuous place.”

With the legislature set to adjourn earlier than expected this month, Michigan legislators worked right up to the end to pass a flurry of bills with the intended effect of reducing friction at nearly all points in the voting process, starting from registration.

Michigan adopted automatic voter registration, a system in which the government uses existing points of interactions with residents to proactively register them, back in 2018, thanks to a different ballot proposition. But lawmakers on Nov. 8 passed a bill sponsored by Tsernoglou that would expand the state agencies tasked with automatically registering someone to vote. In addition to signing people up when they get or update a driver’s license, the state would also register them through interactions with Native American tribal nations, Medicaid applications (though this provision is contingent on a federal blessing) and the Department of Corrections.

As Bolts reported last week, this is the first law in the nation under which people leaving prison would be automatically registered to vote.

Lawmakers also passed a bill that would allow 16 and 17-year-olds to preregister, so that they’re already on the rolls to cast votes once they become eligible at 18. Proponents of this reform, which already exists in some form in 25 other states, say that it helps build civic habits early, and encourages turnout among young voters. Both of these voter registration bills now await Whitmer’s signature. (Editor’s note: Whitmer signed both bills into law on Nov. 30.)

Whitmer signed another bill this month that repealed the state’s ban on paid rides to the polls. This unusual restriction, defended by the GOP, threatened outside groups with criminal charges if they paid to transport people to the polls, limiting get-out-the-vote methods used elsewhere.

Another law that she signed would change the rules for ballot challenges so that votes cast by people who register on the day of the election are no longer automatically entered in “challenged” status, which delays ballot processing. Tsernoglou says this rule benefits voters in college towns like Ann Arbor and East Lansing, where many students use same-day voter registration.

HB 4570, meanwhile, will allow voters to request absentee ballot applications online, codifying and make permanent a process that Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson has already put in place.

Still other legislation passed during this final sprint focused on protecting against false information on the campaign trail, and protecting voting procedures and election workers. One set of bills, also sponsored by Tsernoglou, would require disclaimers on campaign ads produced with AI technology, in an attempt to combat “deepfakes,” digitally-manipulated content that’s increasingly being used to spread political disinformation.

Other reforms would clarify that only the state supreme court may contest the results of a presidential election, and establish a process candidates must follow to petition for judicial review; lawmakers passed those bills to deter frivolous lawsuits of the sort that Trump’s campaign filed in Michigan in the aftermath of the 2020 election. All of these measures also await Whitmer’s signature.

Lawmakers also passed a bill, now on Whitmer’s desk, that would make harassing or intimidating an election worker a crime, up to a felony. (Editor’s note: Whitmer signed this bill and the ones mentioned in the prior paragraph on Nov. 30.) With it, Michigan would join a growing list of states passing laws that have created new criminal charges for people who harass election workers since the 2020 election and its aftermath, which has seen election workers nationwide complain of threats they’ve received.

Where these laws have been proposed, though, some criminal justice reform advocates have raised concerns about the strategy of creating new criminal charges, objecting to measures that increase the footprint of the prison system and pointing out that such measures may needlessly pile onto existing anti-harassment laws.

Earlier this year, Michigan Democrats already adopted another package of landmark reforms meant to implement and fund provisions of Prop 2: These measures established the modalities of early voting, detailed municipality drop box requirements, and codified a system for online absentee ballot tracking. It also allowed voters to sign up on a list to receive mail ballots every cycle, without having to ask for them again.

Whitmer signed this package into law in July.

Brown, the Oakland County clerk, sees the changes brought about by Prop 2 as sorely needed. “From a voting rights perspective, I’d say we finally caught up to a lot of other states,” she said. “We were lacking and lagging for way too long.”

Brown served two terms as a Democrat in the state House from 2009 to 2012, when the legislature was either split or under Republican control. She recalls how difficult it was then to pass voting rights legislation.

“You couldn’t get some of these issues through,” Brown told Bolts. “It took citizens to get together and say, ‘If the legislature can’t do this, we’re gonna do it.’ And that’s how we got those ballot proposals. So I think we made a lot of really good progress.”

When Democrats took control of Lansing last year for the first time since the 1980s, they were meant to have a two-year stint in power. But their narrow 56-54 majority in the state House has been thrown into question: Representatives Kevin Coleman and Lori Stone decided to run for mayor in their respective hometowns of Westland and Warren, and they’ll now leave their office early since they prevailed in those mayoral elections on Nov. 7.

Democrats feel confident they’ll eventually regain a working majority once Coleman and Stone’s seats are filled, since both come from solidly-blue districts. But these special elections may take a while to organize.

Speaker Joe Tate doused some Democrats’ hope that the specials would happen in February to coincide with the state’s presidential primary, telling Bridge Michigan that he doesn’t “see that as feasible.” Bridge Michigan reports that special elections may be held in May, or even as late as August to coincide with another statewide primary. The final decision lies with Whitmer. (Update on Nov. 27: Whitmer has scheduled primaries for both seats on Jan. 30, with general elections to follow on April 16.)

In the meantime, there may be five to eight months in which Michigan has a Senate under Democratic control, but a House divided 54-54 between Democrats and Republicans—a situation that some observers are already calling a recipe for partisan gridlock.

Advocates in the state are nervous that, by the time the specials are held, especially if they’re in August, lawmakers’ attention will have shifted to running for reelection in the November races.

And there’s a lot else that they were asking of lawmakers. Murphy-Kovalick of Voters Not Politicians was hoping they’d pass a bill banning people from carrying guns within 100 feet of polling locations and county boards.

“It’s very disappointing that banning weapons at polling locations didn’t make it across the finish line,” Murphy-Kovalick said, “because open carry of weapons at polling locations is a voter intimidation tactic that has been used in the past, and we would like to avoid that next year.” The bill passed the House but did not make it out of the Senate this year.

Another reform that stalled this year was a proposed Michigan Voting Rights Act, intended to prevent racial discrimination in voting. At least six states have passed such measures in recent years in order to fill in voter protection gaps that have been left by the recent court decisions that weakened the federal Voting Rights Act, explains Aseem Mulji, legal counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, a national organization that advocates for voting rights and endorsed the Michigan proposal.

“There is a common-sense response to the erosion of voting rights at the federal level; states have the power to pass their own VRAs,” he said. “You don’t have to just rely on the federal law. It’s sort of baffling that the idea has just begun to catch on.”

Michigan’s proposed VRA, which didn’t pass either chamber this year, is designed to do just this. One provision would require local governments to get preclearance from the secretary of state or from a state court before making certain voting changes, which would mirror a key section of the federal VRA that was gutted by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013. The package also includes provisions to protect Michigan’s minority groups; for example requiring voting materials to be translated into Arabic and other languages from the Middle East and North Africa, in service of the many people from those regions living in the state.

“It’s worth acknowledging that the state’s taken really tremendous strides towards improving access and freedom to vote,” said Mulji. “And this is really a way to protect the progress the state has made against future backsliding, by saying, ‘we won’t allow you to backslide on any protections to the extent that they result in racial discrimination.’”

Another missed opportunity to shore up voting equity was a bill to end prison gerrymandering. In Michigan, as in most states, people incarcerated in state prisons don’t have the right to vote but, for the purposes of drawing electoral districts, are counted as part of the population where the prison is located rather than where their last address before being incarcerated. This inflates the political power of small, rural areas where prisons tend to be located at the expense of more urban and more diverse areas that tend to suffer a heavier incarceration rate.

The Michigan Senate first took up the issue in September with a hearing in the Ethics and Elections Committee, but the legislation did not advance. For now, Michigan won’t join the other 11 states including Colorado and Virginia that have ended prison gerrymandering.

Murphy-Kovalick doesn’t expect the VRA package or the prison gerrymandering bill to pass a tied House next year. But Tsernoglou doesn’t necessarily think that the next few months will be time lost.

“We really need to have some time to do our work in our offices of getting bills drafted and introduced,” she said. “I think this is absolutely fine for us to have this time right now and it’s also a really great opportunity for us to figure out what we can do on a bipartisan basis.”

She acknowledges that it’s been hard to generate bipartisan consensus on election legislation but thinks it’s still possible.

Whatever happens with the rest of Democrats’ agenda Michigan voters will go into 2024 with stronger protections and easier access to the ballot than they’ve had in past years, and other states are already eying Lansing as a blueprint on how to strengthen democracy. But Murphy-Kovalick also warns that next year could be Democrats’ last opportunity for a while to build on their recent work.

“There are some other things that, if we end up losing a pro-voter majority moving forward, might not ever see the light of day,” said Murphy-Kovalick. “So we’re hoping to get some of these across the finish line next year to make sure that everything is in place to protect our elections, not only in 2024, but moving beyond that.”

Stay up-to-date

Now is the best time to support Bolts

NewsMatch is matching all donations (up to $1,000) through the end of the year. Support our nonprofit newsroom today.