Connecticut’s New Commutation Policy Raises the Bar for Second Chances

After Governor Ned Lamont paused clemency, the pardons board revamped its rules to require “exceptional” reasons to reduce a sentence—and its first hearings under the new policy last week had a different tone.

Kelan Lyons | September 8, 2023

Over his two decades in prison, Bernard Smalls found God, earned his G.E.D., and completed vocational classes, a journey that he thought should qualify him for time off a 50-year sentence.

“I hope that this board recognizes I am not the same person I was 23 years ago,” he said during his hearing before the Connecticut Board of Pardons and Paroles last week. He recounted mentoring young people and encouraging them to stay in school to keep them out of prison.

But members of the board questioned what made Smalls’ case extraordinary. “Participating in programs, that’s something that you’re expected to do,” said Rufaro Page, one of the board members. “Our policy is clear that there has to be something exceptional that occurred.”

“Aside from your receiving a lengthy sentence, I don’t see anything that is exceptional here,” she added. The board denied Smalls’ commutation.

Page was echoing the wording of a new policy, unveiled on July 26, that requires people applying for a commutation in Connecticut to now show “exceptional and compelling circumstances” that merit reducing their time behind bars.

This new commutations policy replaced an earlier one rolled out in 2021 to reduce the long prison sentences that had been handed out in the 1990s and 2000s. Under the leadership of Carleton Giles, a former police officer, the board used the policy to grant 106 commutations. Almost two-thirds of the people whose sentences were reduced were Black.

But Democratic Governor Ned Lamont in April bowed to Republican furor over the commutations and paused clemency, Bolts reported in April. He removed Giles as head of the board, replacing him with Jennifer Medina Zaccagnini. Zaccagnini then put a hold on all commutations and supervised the release of the new policy in late July.

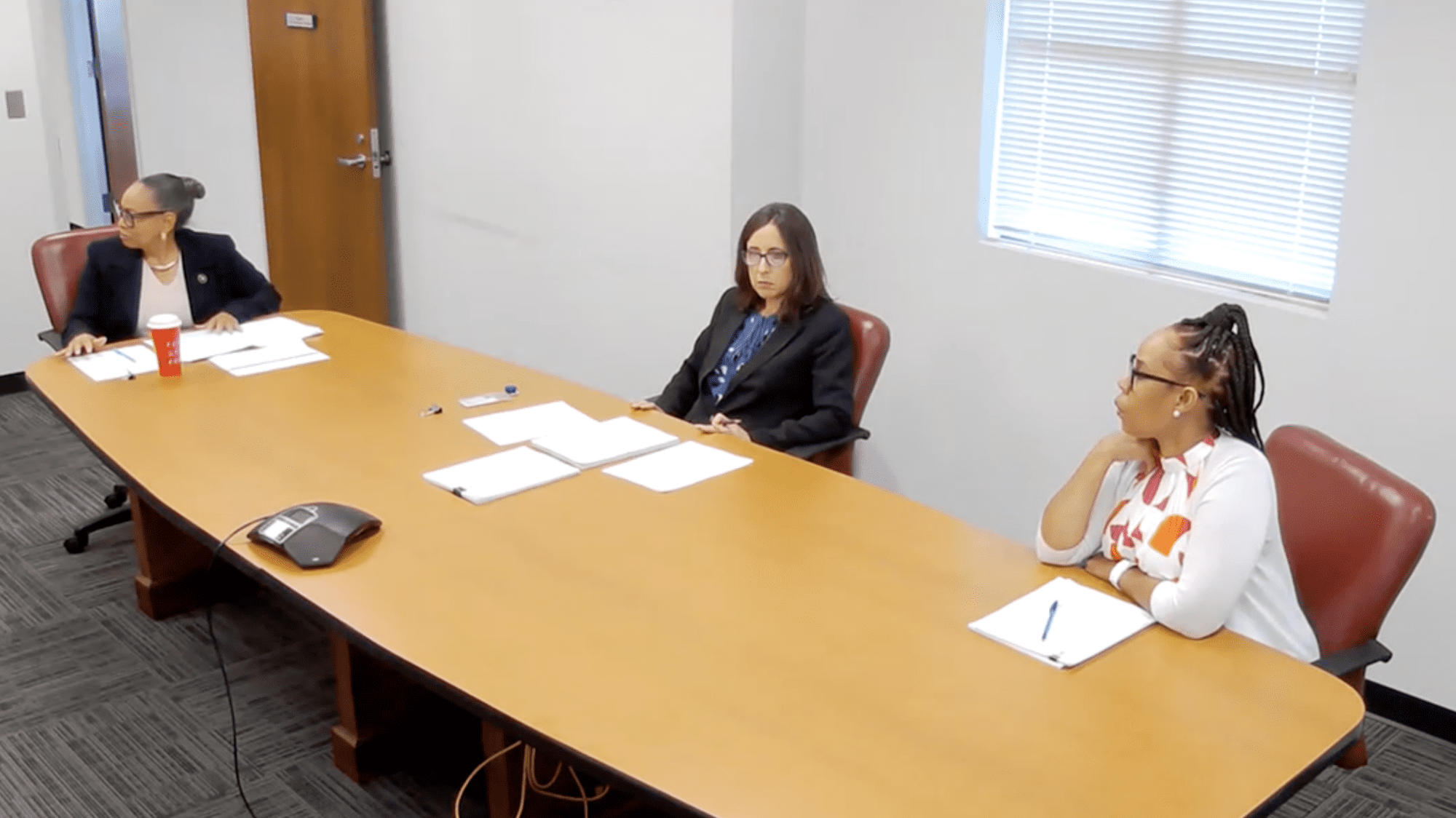

The board’s Aug. 30 hearings—held without Giles or the other two board members who’d been responsible for issuing the 106 commutations—were the first under the new policy, offering a peek into how it might change commutation decisions in Connecticut.

The three applicants heard on that day all fit the general bill of those who received commutations under the last policy. They were all Black or Hispanic, each serving decades in prison for a murder they committed when they were in their teens or early 20s, and all of them had been imprisoned for at least two decades.

One of the applications was granted, and two were denied. Before the board was overhauled, between January and April of this year, it granted 87 percent of commutations applications once they made it to the hearings stage.

Miriam Gohara, a professor at Yale Law School who has represented people applying for commutations, says it will take time to gauge how the revamped board will approach applications. “I think we need to give the board a chance to see what they’re going to do,” she told Bolts.

Still, the tone of these first hearings under the new policy was distinctly different from those held under Giles’ leadership, which focused more on how applicants changed in prison and on their conduct while incarcerated. Previously, board members had asked applicants about educational opportunities they’d taken advantage of, or how they’d use what they learned behind bars once they were free. Applicants’ experiences while incarcerated, by contrast, were mostly sidelined in last week’s hearings; the board appeared to pay more attention than before to what happened before the sentence, to the perspective of victims, and to the details of each crime.

And it was clear that the rule requiring “exceptional and compelling circumstances” also set a higher bar for applicants to clear.

After denying Smalls’ commutation, the board heard from Corey Turner, who has been incarcerated for 27 years and who has maintained that he did not do the crime for which he’s imprisoned. During the hearing, Turner and his attorney recounted his own rehabilitative journey—he too has earned a G.E.D, taken parenting classes, and held jobs while incarcerated.

Turner has also served as a law librarian inside the prison, assisting his peers as a jailhouse lawyer. Someone who was incarcerated with Turner and has since been released from prison wrote a letter of support recounting that Turner had helped fellow prisoners interpret the law and craft legal strategies.

During the 47-minute hearing devoted to Turner’s case, though, panelists only asked him one question about rehabilitation efforts during his lengthy imprisonment.

After one board member asked Turner what was exceptional about his application, he replied, “This is not an environment that’s designed for human beings to flourish,” explaining that instead of turning to despair and violence, he had tried to heal from a traumatic life and become a better father and person. “The only evidence that is compelling that I have to bring before you today, ma’am, is myself, my lived example. That’s all I have. And I hope it’s enough for you.”

“I think what’s compelling or exceptional is me,” he said.

“I commend Mr. Turner for his rehabilitative efforts,” Zaccagnini, the board’s new chair, said later in the hearing. “However, it does not rise to the level of compelling and exceptional that would warrant a commutation of his sentence.”

The board denied Turner’s application. Alex Taubes, who represented him and who was a vocal critic of Lamont’s decision to fire Giles in April, told Bolts after the hearing that Turner’s experience underscores how much Connecticut’s commutation policy has changed.

“They’re no longer providing people with second chances who truly earned them and deserved them,” Taubes said.

Between 2015 and 2019, the Board of Pardons and Paroles granted just five commutations, at which point the board froze the process for two years. This stasis was decried by advocates in the early stages of the pandemic. “There wasn’t a functioning commutations system for a number of years,” Gohara says. Then, in 2021, the board revamped its approach and began accepting applications again; under its new policy, it considered 11 criteria when determining whether to shorten a sentence. Those included an applicant’s conduct while incarcerated, how serious and recent their conviction was, how shortening a sentence could benefit society, and whether an applicant had been rehabilitated while imprisoned.

These changes made what had been a rarely used power into a progressive tool. Board members publicly touted that they were using clemency to offer an avenue of release for incarcerated people who otherwise didn’t have a way out of prison. They began reducing long sentences given to people who committed crimes when they were younger than age 25, an acknowledgment of advances in the scientific understanding of brain development that shows young adults’ brains are still maturing well into their 20s.

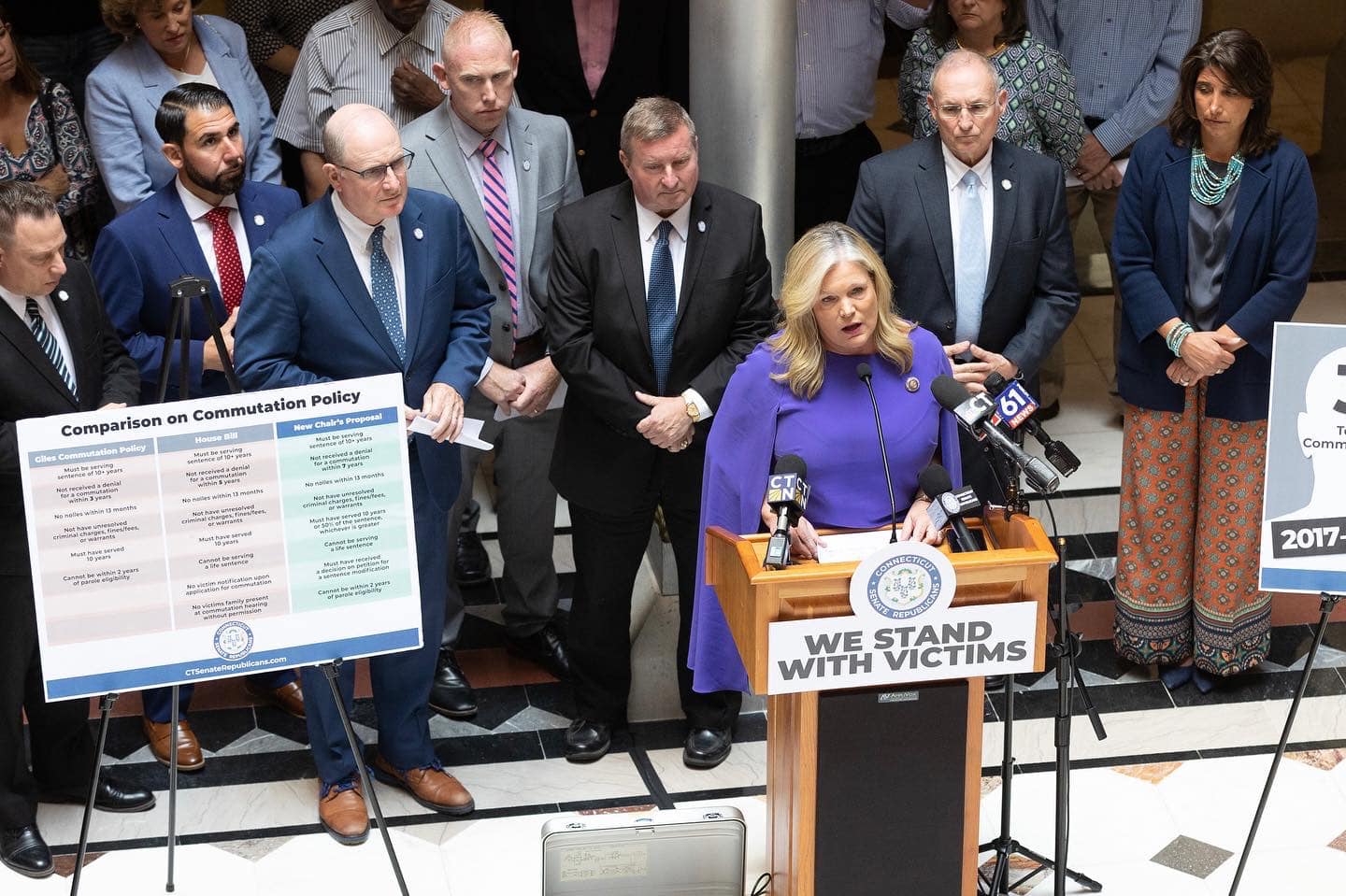

But Republicans blasted the board’s approach, staging an elaborate event earlier this year with victims’ families during which they called on Lamont to make the board stop commutations. The governor’s decision to replace Giles with Zaccagnini then paved the way for the new policy, which replaced the 11 “suitability” standards that were meant to guide board members with the provision requiring “exceptional and compelling circumstances.”

David Bothwell, an advisor for the board, told Bolts in a statement that the new rules improve the process. “This policy puts the onus on the applicant to present to the Board extraordinary and compelling reasons that warrant commutation of sentence,” he said. “It does this through a procedure that is fair, open and transparent, and where victim input is acknowledged, valued, and respected.”

Bothwell said that eliminating the suitability criteria will allow “a broader range of individuals to make their cases to the Board.” He also laid out that, “in making a decision, the board will consider exceptional personal growth and development, efforts to improve his/her surroundings and the lives of those he/she share those surroundings with, the serious nature of the offense, prior criminal history, impact on the victim and victim’s family and the total length of sentence and time served.”

Lamont’s office told Bolts in a statement that the governor is “encouraged that Chairwoman Zaccagnini and the staff at the Board of Pardons and Paroles met with all of the involved parties and developed a revised process that takes into account their concerns.”

This summer, Lamont signed into law a bill that will expand parole eligibility for people convicted of crimes they committed before age 21. The law comes amid a wave of reforms nationwide meant to create more paths to release for people sentenced while young, and it targets a population that Connecticut’s prior commutations policy looked on favorably. Parole applications would be reviewed by the Board of Paroles and Pardons as well.

The Aug. 30 hearing also raised questions about whether applicants who maintain their innocence can still succeed in front of the board.

Although Turner and his lawyer emphasized his rehabilitation when they made their case to the board, his application was also rooted in his claim that he did not commit the crime he was convicted of, which seemed to bother the panel hearing his application.

“We don’t retry cases,” Zaccagnini said. “That is for a court to decide.” At one point Joy Chance, another board member, asked Turner why he never mentioned the victims of his crime. “Ma’am, I didn’t commit this crime,” Turner said. “I’ve been in prison for 27 and a half years for a crime that I didn’t commit.”

Chance doubled down. “Why wouldn’t you have expressed some kind of remorse for the victim, even if you say you didn’t do it?” she asked. “It’s not that I don’t care,” Turner responded. “I didn’t commit this crime.”

While the panelists were deliberating, Taubes interrupted them to say that Turner and he had focused their presentation on Turner’s mentorship, education and rehabilitation, and that it was the board that had brought up the innocence claim. “You’re using his innocence against him, and it is a travesty of injustice,” he said.

Bothwell told Bolts that someone who maintains their innocence can apply for a commutation, and it is not a hindrance to their getting a commutation.

Still, Taubes believes the hearing marked a change from how the previous board approached such cases. He named four clients who maintained their innocence but who received a commutation between 2021 and April of this year, including Norman Gaines, who was released from prison after his sentence was commuted in 2022 and who testified at a legislative hearing in March. “When I was talking to the panel at the Board of Pardons and Parole, that I would do my best to be a beacon of the community, I would like them to know I’ve been keeping my word,” Gaines said.

During the Aug. 30 hearing, the board did commute the sentence of Miguel Sanchez, who had received a 60-year sentence for a murder he committed when he was 17. Sanchez apologized to the family of the young man he killed, acknowledging that his reckless and violent actions profoundly altered the course of not only he and his victim’s lives, but those of their surviving family members, as well.

“I have spent almost 60 percent of my life in prison due to my immature and irresponsible actions as a teenager,” Sanchez said. “However, I am no longer that immature youth. I remain in prison as a matured and educated middle-aged man, who at 45 years old has focused on helping transform not only myself, but others as well through education.”

The board commuted Sanchez’s sentence by 15 years; he could be eligible for a juvenile parole hearing beginning next year. Board members highlighted that he helped teach college classes to his incarcerated peers early in the pandemic, when outside volunteers weren’t allowed in prisons. They noted that his brother, a correctional officer at another state prison, offered to help him navigate a new life outside of prison, should he get released early.

The board did not explicitly ask Sanchez about “compelling and exceptional circumstances,” as they did with Smalls and Turner. They commended his rehabilitative efforts and the programs he has completed in the past 26 years.

“He has done everything possible, and then some,” Zaccagnini said. “He has gone above and beyond to assist others throughout his incarceration and give back.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.