Rhode Island Pair, Once Dogged by Criminal Legal System, Elected to Statehouse

Cherie Cruz and Leonela Felix are joining forces to give people impacted by the system a voice in lawmaking.

Alex Burness | December 1, 2022

About 15 years ago, as a young adult, Leonela Felix would apply for jobs from which she knew she’d get fired.

Felix would lie by omission on applications, declining to mention to employers she’d been previously convicted and jailed over a drug-related felony she says stemmed from a toxic romantic relationship. It was worth lying, she says now, because by the time her managers would find out, “at least I’d have had one paycheck.”

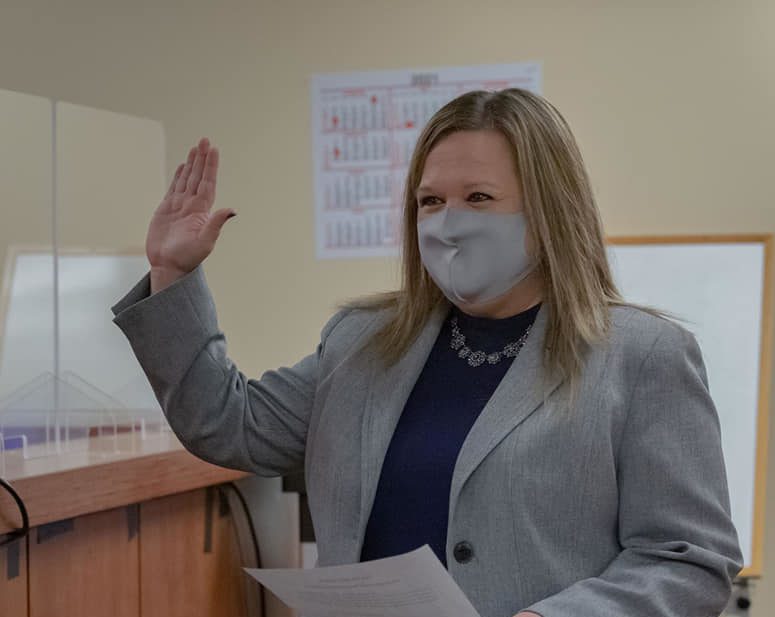

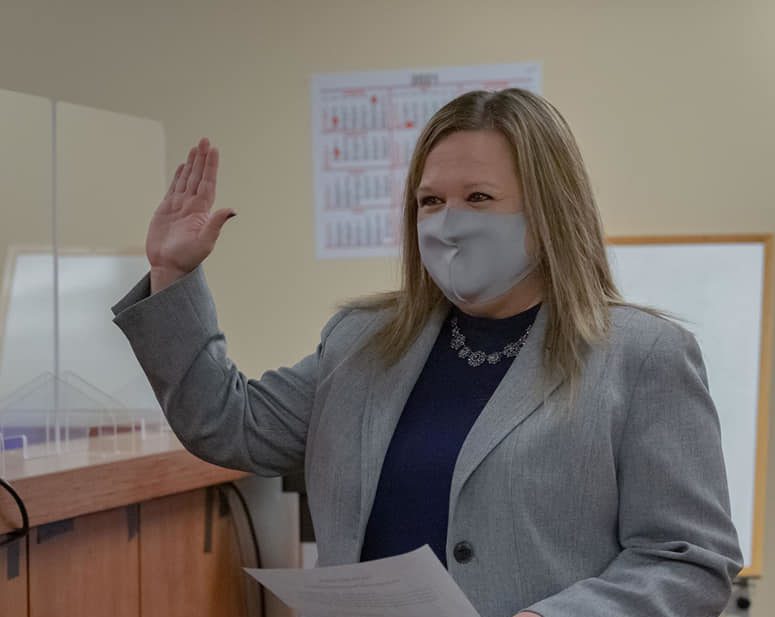

She worked hard to improve her station; as she struggled to find housing and income, she put herself through college, then law school. Two years ago, she ran for and won a seat in the Rhode Island House of Representatives, knocking off an incumbent who defended status-quo policing and sentencing laws, in a Democratic primary.

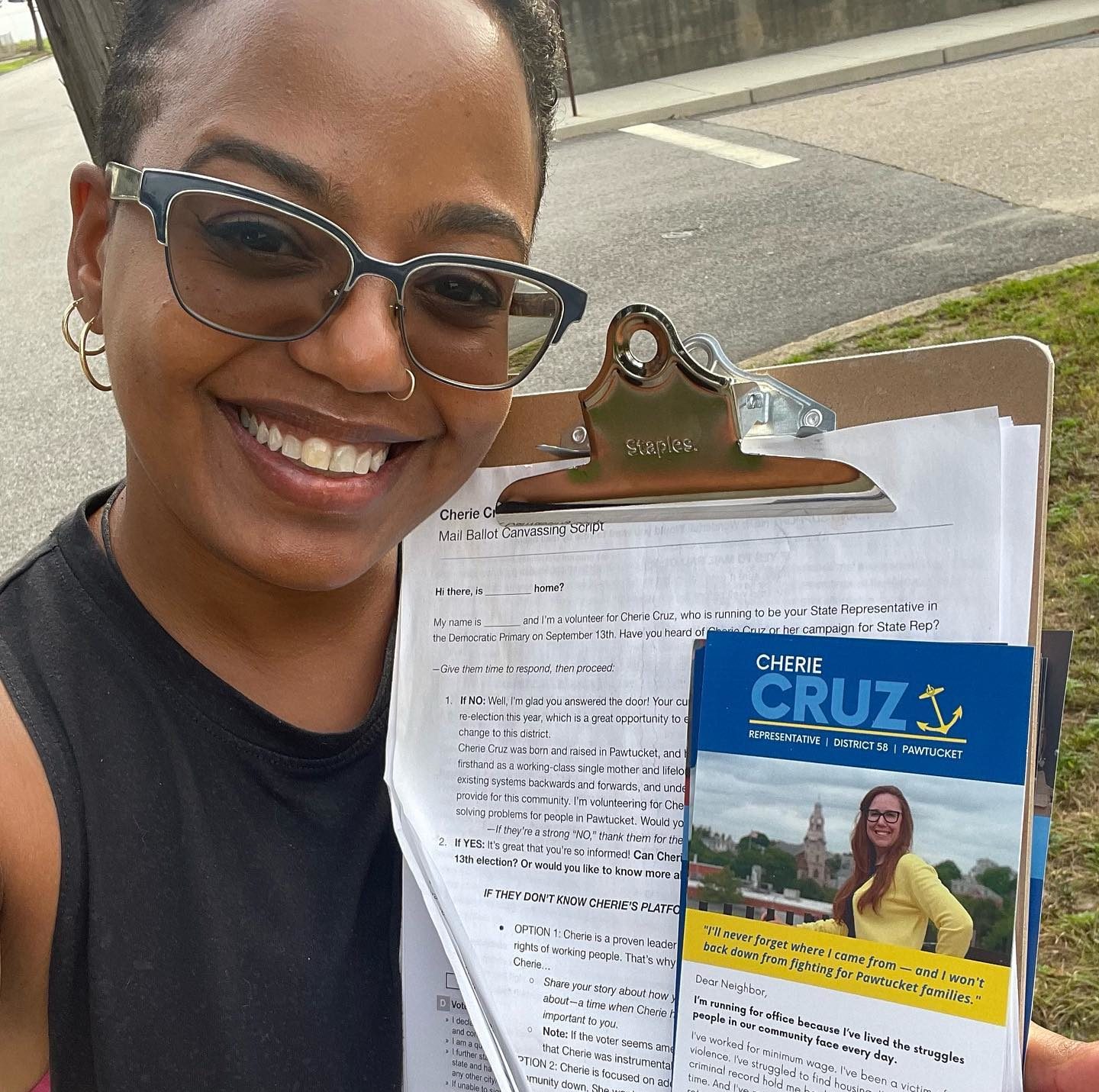

When the Rhode Island legislature convenes its next session on January 4, Felix will no longer be the only lawmaker in Providence who has experienced the criminal legal system from the inside. Cherie Cruz, who like Felix is from Pawtucket, and was also dogged for years by a conviction for a drug felony, won a House seat alongside Felix this fall. Prior to her election, Cruz co-founded the Formerly Incarcerated Union of Rhode Island to support people seeking to move beyond their criminal records.

Cruz and Felix, who have teamed up and supported each other’s campaigns, talked with Bolts in a joint interview shortly after their wins last month. They spoke about what drove them to seek public office, and why people who have navigated the criminal legal system should be seen and heard in policymaking spaces.

Both are bullish on providing more and better opportunities for people mired in the post-conviction slog. That fight is personal: Cruz and Felix say they each only attained stability once their records were sealed and expunged. But those were hardfought processes, and they now want to make things easier on those who come next.

Cruz and Felix say they will work together at the statehouse to help people rebuild their lives from prior criminal-legal run-ins—starting next session with a plan to introduce a “clean slate” bill that would automatically seal many people’s criminal records, emulating reforms that other states have adopted since 2018. They also plan to build on Felix’s work last year making sure that legalized cannabis legislation included automatic record expungement.

When people who’ve been incarcerated enter office, “it makes a world of difference,” says Felix, who has also elevated efforts against solitary confinement and cash bail. She stresses the value of “educating colleagues” about the struggles people face when detained and upon re-entry. “It really does change the dynamics in those rooms.”

Besides promoting climate legislation and gun safety, both also advocate for enabling people to vote from prison, and for better informing people on probation or parole, who, they find, often don’t realize they can vote. Cruz won her primary by only three-dozen votes—which reminded her of the power any one voter can wield.

What will it mean to have a team of two at the statehouse, where previously there was only one of you?

Leonela Felix: The excitement that I feel is something I can’t put into words. It’s so goddamn exciting. It’s just going to be a powerhouse. We keep joking that they’re not going to sit us together because they know we’re going to start good trouble. It’s going to be so important, in terms of educating colleagues, in terms of tag-teaming. There are days with massive amounts of bills, where I can’t be in all places at once. So, we can organize within the legislature. I’m really excited to be able to see what ways we can maximize the resources that we have, and improve them, to better the lives of folks who have been impacted by the carceral system.

Why did you run for office?

Felix: I never wanted to run for office or be elected, because of my background, my criminal history. It wasn’t something I widely shared with people, or ever really owned, until I decided to run. I had done a lot of organizing and advocacy up at the statehouse, and what I’d noticed was that folks representing us really didn’t look like me. They never looked me in the eye or took me seriously. It was my first introduction into politics and to see the way us as regular folks were being treated really stuck with me. I just got mad enough and decided, let’s do it, let’s run for office. The Working Families Party really helped me connect with all the resources I needed to make it to where I am today.

Cherie Cruz: I grew up in the community where I ran for office, several generations there. Both my parents, growing up, didn’t have the right to vote because they were both formerly incarcerated. I also didn’t have the right to vote for many years of my life, because I had felony convictions, and it wasn’t restored until we passed the Right to Vote Act in 2006, which I was on the ground in advocating for. [Editor’s note: The reform enabled people to vote upon release; until then, people on probation or parole could not vote.] So, I’d never thought about politics, similar to Rep. Felix, because of my background. There were barriers for us. We were pushed out of that.

I was at the courthouse one day and a mutual friend of Rep. Felix came up to me and said, ‘Hey, there’s someone running from Pawtucket and she’s got a similar background, and I think you need to reach out to her.’ I just called the [Felix] campaign and said I wanted to help. I started knocking doors and thinking that if she could win and get in, it really could pave the way for the rest of us.

Continuing my advocacy at the statehouse, I was seeing a lot of things in the community not being addressed. We needed somebody who was going to truly be representative of this community—a background in the criminal-legal system, who grew up in poverty, who doesn’t have political ties, and who would really fight. To me, that was the calling.

How does it affect policy debates in the statehouse to have people there who can ground their ideas about sentencing reform or second chances in their lived experience?

Felix: It makes a world of difference. It really does change the dynamics in those rooms. A lot of folks just don’t have that experience and, quite frankly, many of them tend to say that if you got into legal issues, you deserved it. That you’re not deserving of our empathy or of us changing laws to benefit you or others in your position. We tend to blame the individual versus looking at the macro level, at the system that does impact particularly poor people and people of color.

Say, with record expungement—in the minds of many of my colleagues, it’s like it’s easy to get an expungement, where you can just walk in and just petition. So I’ve been giving them the raw experience. Like, have you ever had to get your record expunged? The answer for all of them was no. They don’t know that you have to do this extra step and this other extra step, and it’s still not complete. It was really important to make them see something more than the abstract. It was very powerful for me to be able to communicate to them in that way and to educate them in the realities of everyday life for someone who is formerly incarcerated.

Cruz: I think about when I used to testify at the statehouse, and no one would look at me. I mentioned in my testimony how I had my drug felony and another charge for over 25 years, with children—single mom, on welfare, in and out of homelessness, no employment—and the thing that lifted everyone’s head up was that I had two degrees from Brown University, one with honors. My advocacy, my community work, my policy work was pushed aside until I mentioned the degrees, and then they looked up for a minute.

The lived experience of people who’ve been involved with the criminal legal system—you can’t learn it in a book. You have to go through it to truly understand it. It’s a benefit to any legislature, or any agency, to have people with that type of education. The culture is starting to change a bit, where it’s seen as credibility.

Whether through prison gerrymandering, or the fact that people cannot vote from prison, incarceration strips people of investment in their communities in Rhode Island. How could those in jail and prison be made to have more of a stake?

Felix: We talk about how voting is your voice. It’s the way that you literally can make change for the better for your community—we want folks to feel more connected to their communities and feel integrated. When we alienate people from these processes, what we’ve created is someone who’s isolated. By allowing them to cast ballots and use their voice for change, what we’re saying is, you are a part of this community.

Representative Felix, you’re a lawmaker now, but does the fact that you were incarcerated still impede you?

Felix: I was barred from education after I got out. I couldn’t go to school. Housing, forget about it. Employment, forget about it. I had to live on couches or with friends. It impacted every area of my life. I am privileged and I recognize that for many folks it’s a lifelong struggle, a blacklist. Now, luckily, it doesn’t affect me. But it definitely did. That’s the reason I fought to get to where I am, because no one should go through that. How do you start your life over when they continue to shackle you in so many ways?

Lawmakers in Rhode Island make $17,000, and I wonder to what extent that’s a barrier to more people with your backgrounds running for office. What percentage of people coming out of jail and prison could even consider vying for a job that pays a poverty wage?

Felix: It’s not a place for working families, not a place we’re supposed to be a part of. It’s by design. It didn’t happen magically that we are in office; it takes so much effort and infrastructure. We’re really trying to figure out how we can make it work for everyday people. It just takes a little bit more planning, but it’s doable.

Cruz: I’m glad I’m hearing this. My employment now puts me with the most money I’ve ever had in my life, which is still lower-working class, where I can barely pay rent. I’m glad to hear Leo say it’s doable, because it may be I’m unemployed or let go if I can’t go down in hours to do this.

If we’re talking about someone who still has felonies on their record, I’m not sure how, if they still have those housing and employment barriers, they could do this. For me, if the legislature just gave enough to pay rent, it’d be fine. But it’s not enough.

How do your lenses affect your approaches to legislation that may have little, on paper, to do with a jail or a prison or a court system—climate justice issues in areas with poor air, or affordable housing?

Cruz: A family is an ecosystem and a community is an ecosystem. Growing up in poverty, my youngest son was lead-poisoned. What are we doing when children are getting poisoned? These are the kids who are going to start struggling in schools. These are the kids who aren’t going to have opportunities. These are the kids who are going to end up in cages. You have to worry about surviving versus thriving. I think environmental justice, housing justice are directly impacting whether people survive or thrive.

Felix: Having green spaces for adults and kids is better for your mental health, it’s better for your breathing. Slowly but surely, we’re taking away a lot of green spaces, things that benefit communities, and for what? To build luxury housing, or another parking lot?

What advice do you have for anyone who might see themselves in your stories and consider seeking elected office?

Felix: It’s critical that we have folks that are directly impacted by these inequalities we seek to change, and without their presence in the rooms that are deciding on them and their families and future generations, those voices aren’t going to be heard. Despite all the challenges we talk about, don’t let it be a barrier to wanting to be a public servant. And there are so many other ways you can help, in terms of volunteering, knocking doors, making calls. Don’t let your mistakes be an obstacle to that.

Cruz: I want to empower more people to be leaders, in whatever space. It could be in your home, your community, with the school community, with the school board, at the state legislature. It could be anywhere.

I always joke that I’ve started my succession planning, because this was about giving people hope that you can do it, too. Who’s next? How can we tag-team someone else in, and help mentor them? I didn’t see this in myself at first, and sometimes you need others to point out that you’re incredible and that what you’re saying needs to be heard.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.