“Fool Me Once”: Scandals and Abuses Fuel Unease Toward ‘Reform’ Talk in Los Angeles Sheriff Race

Alex Villanueva’s tenure has inspired renewed efforts to bolster oversight of his department—no matter who wins this year’s election.

Piper French | May 31, 2022

This is the second in our series on California sheriff departments in the run-up to the June 7 elections, alongside stories on Alameda and San Diego.

Editor’s note: Robert Luna and Alex Villanueva clinched the Top 2 spots in the June 7 primary; Luna then prevailed in the November general election.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva has made a national name for himself as a swaggering, autocratic leader hostile to any challenge, however minor, to his power. He has alternately denied the existence of the murderous deputy gangs that plague his department, and said he’s neutralized them. Under Villanueva, the department covered up at least one incident of deputy violence against someone in custody. He has defied subpoenas from an oversight commission established by LA County’s governing body, the five-member Board of Supervisors. He has bullied and maligned those who question his authority: suggesting that the supervisors, all women, needed to be “taken to the shed and they need to be beat down so they start doing their job”; calling LA County’s Inspector General a Holocaust denier; and threatening to use the power of his agency to investigate a LA Times reporter assigned to cover his department. Most gravely, Villanueva has presided over a force that has killed dozens of civilians, and a jail system, the largest in the county, in which 55 people alone died in 2021. An exhaustive list of scandals and abuses could fill a book.

Villanueva is up for reelection this year: the primary is set for June 7, and if he does not get over 50 percent of the vote, there will be a general election in November. It’s hard to imagine how a man who has garnered a reputation as “the Trump of LA” could win reelection in the multiracial, heavily working class, staunchly Democratic panoply that is LA County. For everyone from centrist Democrats to the activist left, four more years of Villanueva is an unthinkable prospect. But none of Villanueva’s eight challengers has raised much money or emerged as a major threat. “It really feels like a very unsettled race,” said David Levitus, the Executive Director of LA Forward Action, a local progressive member group.

A county-wide race in a county of ten million people is expensive, and a sitting sheriff has only been defeated once in over a century—in 2018, when Villanueva ousted then-Sheriff Jim McDonnell, who took office in 2014 after the previous elected sheriff, Lee Baca, resigned amid a corruption scandal that ultimately ended in his criminal conviction. Villanueva himself ran on a reform platform in 2018, campaigning to “clean house” at the department and garnering the support of many Democratic clubs and even progressive organizations. He then broke nearly every promise he made during that campaign, alienating his former supporters; the LA County Democratic Party has since called for his resignation. “A lot of people were burned really bad,” said Levitus. “They’re like: fool me once.”

This hesitance speaks to a growing suspicion about the department itself—one that is already fully realized in much of Los Angeles’s activist left.

“The people who really control the ground [in LA]—they fundamentally don’t believe the sheriff’s department should exist,” said Lex Steppling, Director of Campaigns and Policy at Dignity & Power Now, an LA-based abolitionist organization that fights for currently and formerly incarcerated people. Supporting any candidate for sheriff—who, by virtue of California law, must have a law enforcement background—is in direct conflict with many people’s politics, and there is understandable skepticism about how much one person can change a department with an entrenched history of violence.

Many stakeholders believe it’s more important to focus time and energy on limiting the sheriff’s power, no matter who ends up in the seat, and are pushing for an amendment to the LA County charter that would bolster county and civilian oversight of the department. For others on the left, however, ousting Villanueva could still make a material difference to those most affected by the sheriff’s department. “On the other hand,” said Steppling, “you have people saying, Yeah, but you know, it does exist—so while it exists, do you want Villanueva to win again?”

It’s worth noting that my own experience with LASD has not been limited to reporting on the department. Almost exactly two years ago, I was arrested by Los Angeles Sheriff’s deputies for violating a countywide curfew while protesting the police murder of George Floyd, and held in the back of a freezing cold bus for approximately five hours, my hands ziptied behind my back. The arrest momentarily propelled me past the line that separates the experience most white, middle-class Angelenos have with LASD—minimal—from that of communities most often targeted by the department: Black and Latinx people, the poor and unhoused, people struggling with mental illness, and the department’s vocal critics. When I was released, I realized I didn’t know much about the agency that had just exerted total power over my life, and neither did most other middle-class white people I knew in LA.

In the intervening years, the public image of the sheriff’s department has changed quite a bit. The deputy gangs that fester in the department are now national news, thanks to the dedicated work of a few people and a 15-part series by local independent reporter Cerise Castle, who has provided a comprehensive account of their inner workings and human toll. In a statement, LASD denied the existence of gangs within the department, referencing “unproven allegations regarding deputy sub-groups,” and added: “due to multiple active investigations and pending ligation [sic], we are unable to comment further at this time.”

Slow but sure progress has been made by local organizations working to establish oversight and accountability for LASD. But at the same time, very little has changed. Jail deaths and deputy shootings have risen every year since Villanueva took office, and the sheriff is increasingly defiant of attempts to curb his authority. “He’s such a loathsome figure, and he just gets more and more antagonistic,” Steppling told me.

This history of illusory reforms has left Los Angeles voters who care about ending the well-documented abuses of the department in an awkward position.

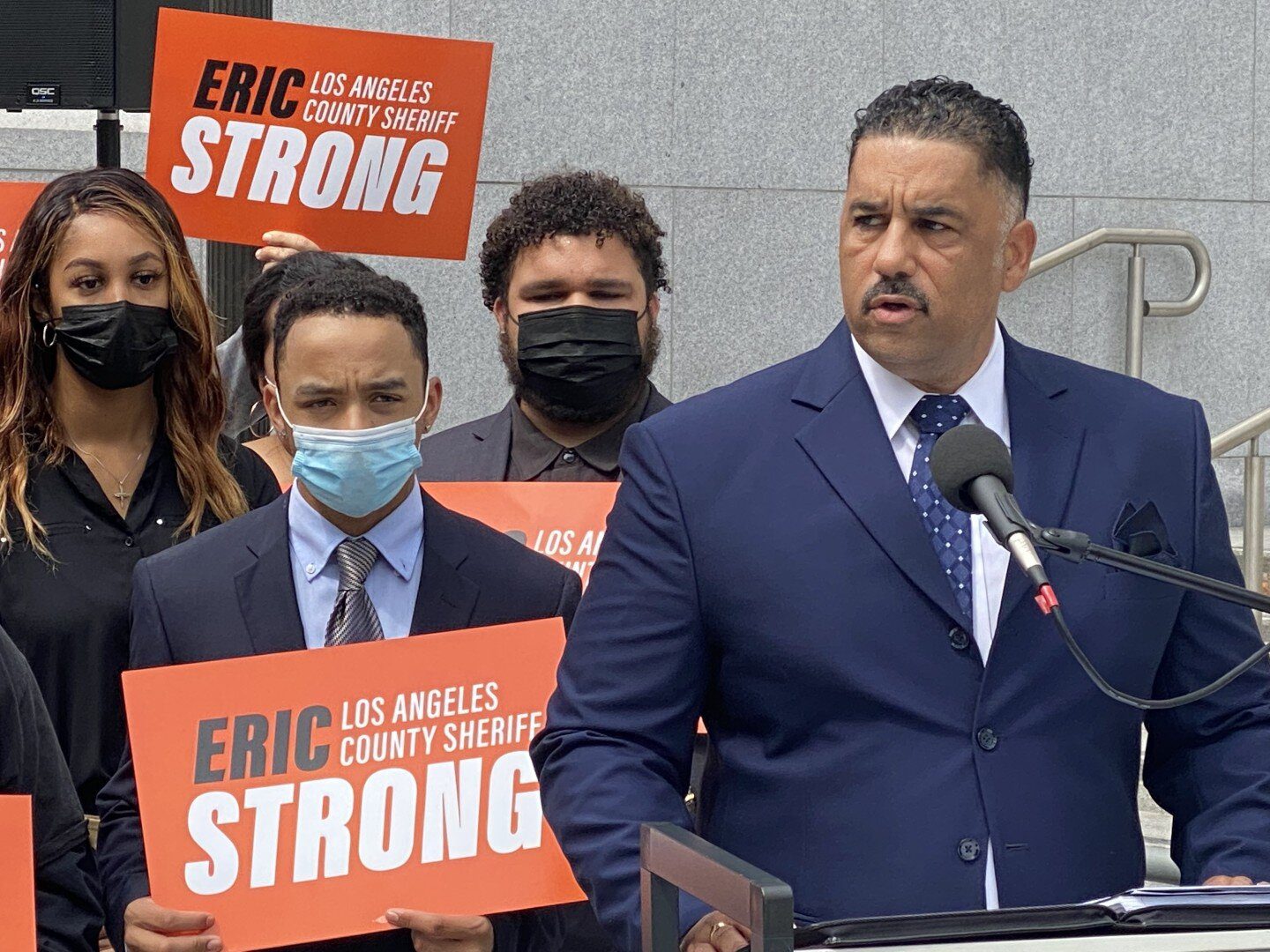

Among the crowded field of candidates seeking to unseat Villanueva, Eric Strong’s policy platform reflects many of the immediate demands from the activist left in Los Angeles. An almost 30-year department veteran, Strong has centered his campaign around eliminating deputy gangs, supporting alternatives to incarceration such as mental health services, and establishing full data transparency and accountability to impacted families. He also opposes the construction of a new jail to replace Men’s Central Jail, a decrepit facility that local activists have been struggling to shut down for years.

Strong, who is Black, has spoken of having family members incarcerated and even losing a loved one to police violence. In an interview, he recalled his first negative experience with law enforcement: “I was 16 years old, driving my dad’s car—and getting pulled over, getting pulled out of the car, thrown on the ground, roughed up a little bit. And I know I hadn’t done anything wrong.”

Strong’s dad was also a cop, so to him, the two officers who’d treated him poorly were just outliers. But over the years, as he started working for the Compton police and then became a deputy when that department got absorbed into LASD, he began to see how the problem went beyond individual officers. At LASD, he spent several years in internal affairs, where he says investigating deputies accused of wrongdoing helped him realize the extent of misconduct and corruption inside the department. “If there’s a policy violation or a crime, A to Z, somebody in this department has done it,” Strong said. “And that was very shocking to me.”

Strong also noticed a pattern of deputies seeking to retroactively justify their actions rather than evaluating them honestly—he called it the “write it right” mode of filing reports. “If it’s a bad shooting, we need to call it a bad shooting, period,” he told me. And pervasive cronyism meant that some deputies, especially people of color, had careers ruined over missteps, while serious misconduct barely affected the trajectory of others. While he was at Internal Affairs, he said, “We saw a new emergence of deputy gangs, particularly in our jails.” An investigation he led into a 2010 Christmas party brawl between members of the 3000 Boys, a gang that started at Men’s Central Jail, culminated in the termination of six deputies, though he says still more should have been fired.

As the primary nears, Strong has accrued endorsements from a number of local Democratic clubs and progressive groups, including the Progressive Asian Network for Action and LA Forward Action. Levitus said that though he was fully prepared to forgo a primary endorsement and take a broader anyone-but-Villanueva stance, his membership was surprised and impressed by Strong. “We felt like he was well positioned to go in there and try to clean up the department as much as possible, given the disaster that it is,” Levitus said. “I wish I had known about him sooner.”

For months, Strong struggled to gain traction and raise the type of money that would boost his name recognition. “It just comes down to: is his campaign going to get the resources needed to platform itself?” Steppling asked. “If Strong is able to platform himself, I believe he’ll win.”

With Villanueva dug in and openly scornful of anyone who questions him, he has many challengers promising to reform the department, calling out deputy gangs and paying lip service to transparency and accountability. Much of the Los Angeles Democratic establishment is split between two other candidates: Cecil Rhambo and Robert Luna. Both men have garnered endorsements from a long list of unions, Democratic clubs, and local and state politicians, though there is plenty in both of their records to undercut any reformist claims.

Rhambo has a history of on-the-job shootings and was one of two assistant sheriffs during a jail abuse scandal that sent both of his superiors, Sheriff Baca and Paul Tanaka, to federal prison (Rhambo went on to testify against both men, but an ACLU class action suit alleged that he had also been aware of abuse inside the jail). Under Luna’s watch, the Long Beach Police Department targeted gay men in sting operations until as recently as 2016, took pains to conceal and destroy internal communications, and spent tens of millions settling use of force, wrongful death, and civil rights lawsuits. Police Scorecard, a site that compiles and evaluates data from police departments around the country, ranked Long Beach PD the second-worst in the state.

Luna’s campaign emailed a statement defending his record at Long Beach PD and emphasizing that he is “the only major candidate in the race who comes from outside the sheriff’s department.” Rhambo’s campaign didn’t respond to my questions.

For some, the fact that prominent groups and officials are still taking these candidates seriously despite their troubling records is further evidence that the election is a red herring. “Who’s to say that the next sheriff won’t be as bad or worse, right?,” asked Andrés Dae Keun Kwon, an ACLU lawyer and LASD critic. “It’s hard to imagine, but it can happen. I mean, it happened with Villanueva.”

One of Villanueva’s strongest critics has been the coalition Check the Sheriff, which includes local racial justice and immigrants’ rights organizations like the ACLU SoCal, Black Lives Matter LA, Dignity & Power Now. The coalition came together in February 2019, just a few months after Villanueva was elected. “Some folks started asking, do we need to recall this guy?” Kwon, an active member, recalled. “After some healthy conversation, we concluded that what we really needed was structural change. I mean, if you get rid of the head of the monster, the monster is still there. It’s gonna grow another head.”

Right now, only voters can remove Villanueva, but a more law-enforcement friendly Board of Supervisors could further empower him by jettisoning two, relatively recent mechanisms for outside scrutiny: the Office of Inspector General and the Civilian Oversight Commission. The coalition is accordingly pressing for an amendment to the LA County charter that would give the Board of Supervisors impeachment powers, clarify its authority over the sheriff’s department, and codify civilian and county oversight. Strong is the only candidate in the race who has publicly stated his support for Check the Sheriff’s charter amendment.

The coalition is also working on ending the targeted harassment of families who have spoken up about the deaths of their loved ones at the hands of LASD. A joint report last year documented how sheriff’s deputies have repeatedly tailed, surveilled, pulled over and searched, arrested without cause, recorded, and taunted the family members of Paul Rea and Anthony Vargas. “What these families have been facing is persecution by the state,” Kwon said. “It would actually meet the definition of persecution in refugee law.”

For people who have been on the receiving end of the department’s violence, this race is especially painful—and complicated. Some have thrown their weight behind Eric Strong; others are avoiding the race altogether, or focusing on other organizing goals. Kwon noted that most of the impacted families in the Check the Sheriff coalition wanted nothing to do with the race.

Jonetta Ewing first encountered Strong on Instagram. Ewing’s partner, Dijon Kizzee, was killed by sheriff’s deputies in August 2020 while riding his bike in South LA. While logged into a shared ‘Justice for Dijon Kizzee’ account, she came across an Instagram post of Strong’s that referenced his candidacy. “What are you going to do [to] help the families that have lost loved ones to the LASD?” she asked.

To her surprise, Strong wrote back. “This man sent his condolences,” she told me. “That’s the only one I have heard in almost two years.” No one else associated with the sheriff’s department had apologized to her for Kizzee’s killing, and Strong’s willingness to do so meant something to her. They started messaging, and he gave her his phone number. “He was just open,” she said. “What other police do that?”

Recently, Ewing organized a Zoom call where Strong met with several families of other people killed by LASD deputies. She says it took time to convince others to join. “You know, the families—we’re angry and we’re hurting,” she said. “That’s going against everything that we protested—saying fuck the police and then trying to work with the police?” But from her perspective, the meeting had gone well. “He was on there for like two, three hours,” she said. “He let everybody speak.”

Ewing can’t vote for Strong (she lives in neighboring Kern County) but she’s been making up for it by telling everybody she can about him. “I just feel like this is our chance,” she said. She compared the election to the 2020 presidential race, and the most recent Los Angeles District Attorney race: Joe Biden and George Gascón were both imperfect, she said, but they were better than their alternatives.

Helen Jones, an organizer with Dignity & Power Now, felt warier. Her troubles with the LASD go back to well before Villanueva became sheriff: Jones’s son, John Horton, died under suspicious circumstances at Men’s Central Jail in 2009. She believes he was beaten to death by members of the 3000 Boys gang, and settled a wrongful death lawsuit with the county in 2016. Practically ever since Horton’s death, she has been organizing to reduce the power of the sheriff alongside DPN and Check the Sheriff. The day before we spoke, she attended a meeting where the Civilian Oversight Commission had agreed to bring the amendment to the Board of Supervisors. “It’s moving forward,” she said.

Jones had attended a sheriff candidate forum and came away totally unimpressed by nearly all of the candidates. She appreciated what Strong had to say, especially regarding the closure of Men’s Central Jail, an issue close to her heart. But it was hard to countenance supporting any candidate with such a long history at LASD, or to trust that anyone with that much time inside the department wouldn’t just bring more of the same. “I just feel we don’t need nobody that’s tied to the Sheriff Department,” she told me.

Strong told me he understood that perspective, and that he’s glad that disillusionment with Villanueva has created a higher bar for candidates seeking to replace him. But he took pains to distinguish his record at LASD from those of opponents like Rhambo or former LASD division chief Eli Vera. “I’ve always been somebody, throughout my career, that has spoken out,” he said, referencing Rhambo and Vera’s close relationship to disgraced former sheriff Baca and undersheriff Tanaka. (Vera’s campaign also did not respond to a request for comment).

Jones thinks the law requiring candidates for sheriff to have a law enforcement background needs to change, and even though she doesn’t support any particular candidate, she hopes that whoever becomes sheriff will dismantle the deputy gangs. “Get rid of them,” she said, “It has no place.” She is still focused on working to tear down Men’s Central, the jail where her son died. “And at the same time,” she told me, “I wish that a forensic team can also go through there and spray Luminol everywhere.” She said she wants to see how much blood is there.

*This story was updated to include a statement LASD sent after publication.